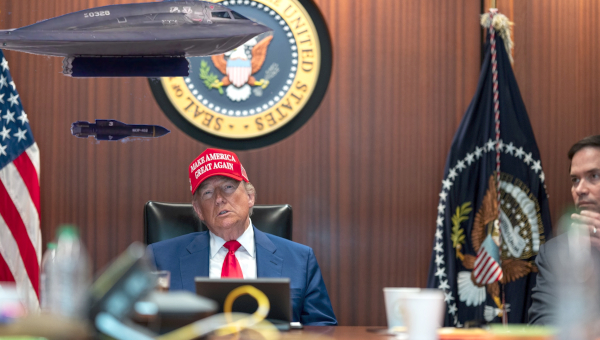

The United States stands at the endpoint of a long series of attacks on democracy, and the choices faced by the American public today point to the divide between those who are committed to democracy and those who are not. Debates over whether Donald Trump was a fascist or Hillary Clinton was a right-wing warmonger and tool of Wall Street were a tactical diversion. The real questions that should have been debated include: What measures could have been taken to prevent the United States from sliding further into a distinctive form of authoritarianism? And what could have been done to imagine a mode of civic courage and militant hope needed to enable the promise of a radical democracy? Such questions take on a significant urgency in light of the election of Donald Trump to the presidency. Under such circumstances, not only is the public in peril, it is on the brink of collapse as the economic, political, and cultural institutions necessary for democracy to survive are being aggressively undermined. As Robert Kuttner observes:

“It is hard to contemplate the new administration without experiencing alarm bordering on despair: Alarm about the risks of war, the fate of constitutional democracy, the devastation of a century of social progress. Trump’s populism was a total fraud. Every single Trump appointment has come from the pool of far-right conservatives, crackpots, and billionaire kleptocrats. More alarming still is the man himself – his vanity, impulsivity, and willful ignorance, combined with an intuitive genius as a demagogue. A petulant fifth-grader with nuclear weapons will now control the awesome power of the U.S. government. One has to nourish the hope that Trump can yet be contained. Above all, that will take passionate and strategic engagement, not just to resist but to win, to discredit him and get him out of office while this is still a democracy. We can feel sick at heart – we would be fools not to – but despair is not an option.”1

A Call for Resistance

Kuttner rightly mediates such despair with a call for resistance. Yet, such deep-seated anxiety is not unwarranted given the willingness of contemporary politicians and pundits during the 2016 presidential battle to use themes that echoed alarmingly fascist and totalitarian elements of the past. According to Drucilla Cornell and Stephen D. Seely, Trump’s campaign mobilized a movement that was “unambiguously fascist.”2 They write:

“We are not using the word ‘fascist’ glibly here. Nor are we referencing only the so-called ‘alt-right’ contingent of his supporters. No, Trump’s entire movement is rooted in an ethnic, racial, and linguistic nationalism that sanctions and glorifies violence against designated enemies and outsiders, is animated by a myth of decline and nostalgic renewal and centered on a masculine cult of personality.”3

Large segments of the American public, especially minorities of class and color, have been written out of politics over what they view as a failed state and the inability of the basic machinery of government to serve their interests. As market mentalities and moralities tighten their grip on all aspects of society, democratic institutions and public spheres are being downsized, if not altogether disappearing. As these institutions vanish – from public schools to healthcare centers – there is also a serious erosion of the discourses of community, justice, equality, public values, and the common good. This grim reality has been called a “failed sociality” – a failure in the power of the civic imagination, political will, and open democracy.4

As the consolidation of power by the corporate and financial elite empties politics of any substance, the political realm merges elements of Monty Python, Kafka, and Aldus Huxley. With the election of Donald Trump, the savagery of neoliberalism has been intensified with the emergence at the highest levels of power of a toxic mix of anti-intellectualism, religious fundamentalism, nativism, and a renewed notion of American exceptionalism. Mainstream politics is now dominated by hard-right extremists who have brought to the center of politics a shameful white supremacist ideology, poisonous xenophobic ideas, and the blunt, malicious tenets and practices of Islamophobia.

The older political establishment’s calls for regime change and war are now supplemented by the discourse of state sanctioned torture, armed ignorance, and a deep hatred of democracy. Neoliberalism, with its full-fledged assault on the welfare state and public goods, the destruction of the manufacturing sector, and a dramatic shift in wealth to the upper 1 per cent, has destroyed the faith of millions in democracy, which lost its power to contain the rich and the rule of financial capital. With the erosion of the social contract and the increasing power of the rich to control both the commanding institutions of society and politics itself, democracy has lost any legitimacy as a counter weight to protect the ever widening sphere of people considered vulnerable and disposable. The result has been that the dangerous roadmap to neo-fascist appeals have gained more and more credence. The end result is that large portions of the American public have turned to Trump’s brand of authoritarianism. The future looks bleak, especially, for youth in neoliberal societies as they are burdened with debt, dead-end jobs, unemployment, and, if you are black and poor, the increasing possibility of being either incarcerated or shot by the police.5 The United States has become a war culture and immediate massive forms of resistance and civil disobedience are essential if the planet and human life is going to survive.

There can be little doubt that America is at war with its own ideals and that war is being waged against minorities of color and class, immigrants, Muslims, and Syrian refugees. Such brutality amounts to acts of domestic terrorism and demands not only massive collective opposition but also a new understanding of the conditions that are causing such sanctioned violence and the need for a fresh notion of politics to resist it. This suggests putting democratic socialism on the agenda for change.

Struggle for Democratic Socialism

The struggle for democratic socialism is an important goal, especially in light of the reign of terror of the existing neoliberal mode of governance. It is crucial to remember that as a firm defender of the harsh politics and values of neoliberalism, Trump preyed on the atomization and loneliness many people felt in a neoliberal social order that derides dependency, solidarity, community, and any viable notion of the commons. He both encouraged the fantasy of a rugged individualism and toxic discourse of a hyper-masculine notion of nativism, while at the same time offering his followers the swindle of a community rooted in an embrace of white supremacy, a white public sphere, and a hatred of those deemed irrevocably other. The ideology and public pedagogy of neoliberalism at the root of Trump’s embrace of a new authoritarianism must be challenged and dismantled ideologically and politically.

Yet, the task of challenging the new authoritarianism will only succeed if progressives embrace an expansive and relational understanding of politics. This means, among other things, refusing to view elections as the ultimate litmus test of democratic participation and rejecting the assumption that capitalism and democracy are synonymous. The demise of democracy must be challenged at all levels of public participation and must serve as a rallying cry to call into question the power and control of all institutions that bear down on everyday life. Moreover, any progressive struggle must move beyond the fragmentation that has undermined the left for decades. This suggests moving beyond single issue movements in order to develop and emphasize the connections between diverse social formations. At stake here is the struggle for building a broad alliance that brings together different political movements and, as Cornell and Seely observe, a political formation willing to promote an ethical revolution whose goal “is not only socialism as an economic form of organization but a new way of being together with others that could begin to provide a collectively shared horizon of meaning.”6

Central to a viable notion of ideological and structural transformation is a refusal of the mainstream politics of disconnect. In its place is a plea for broader social movements and a more comprehensive understanding of politics in order to connect the dots between, for instance, police brutality and mass incarceration, on the one hand, and the diverse crises producing massive poverty, the destruction of the welfare state, and the assaults on the environment, workers, young people and women.

One approach to such a task would be to develop an expansive understanding of politics that necessarily links the calls for a living wage and environmental justice to demands for accessible quality healthcare and the elimination of conditions that enable the state to wage assaults against Black people, immigrants, workers and women. Such relational analyses also suggest the merging of labour unions and social movements. In addition, progressives must address the crucial challenge of producing cultural apparatuses such as alternative media, think tanks and social services in order to provide models of education that enhance the ability of individuals to make informed judgments, discriminate between evidence based arguments and opinions, and to provide theoretical and political frameworks for rethinking the relationship between the self and others based on notions of compassion, justice, and solidarity.

Crucial to rethinking the space and meaning of the political imaginary is the need to reach across specific identities and to move beyond single-issue movements and their specific agendas. This is not a matter of dismissing such movements, but creating new alliances that allow them to become stronger in the fight to not only succeed in advancing their specific concerns but also enlarging the possibility of developing a radical democracy that benefits not just specific but general interests. As the Fifteenth Street Manifesto group expressed in its 2008 piece, “Left Turn: An Open Letter to U.S. Radicals,” many groups on the left would grow stronger if they were to “perceive and refocus their struggles as part of a larger movement for social transformation.”7 Any feasible political agenda must merge the pedagogical and the political by employing a language and mode of analysis that resonates with people’s needs while making social change a crucial element of the political and public imagination. At the same time, any politics that is going to take real change seriously must be highly critical of any reformist politics that does not include both a change of consciousness and structural change.

If progressives are to join in the fight against authoritarianism in the United States, they will need to create powerful political alliances and produce long-term organizations that can provide a view of the future that does not simply mimic the present. This requires aligning private issues to broader structural and systemic problems both at home and abroad. This is where matters of translation become crucial in developing broader ideological struggles and in fashioning a more comprehensive notion of politics. Movements require time to mature and come into fruition and depend on an educated public that is able to address both the structural conditions of oppression and how they are legitimated through their ideological impact on individual and collective attitudes and modes of experiencing the world. In this way radical ideas can be connected to action once workers and others recognize the need to take control of the conditions of their labour, communities, resources, and lives.

Struggles that take place in particular contexts must also be associated to similar efforts at home and abroad. For instance, the ongoing privatization of public goods such as schools can be analyzed within increasing attempts on the part of billionaires to eliminate the social state and gain control over commanding economic and cultural institutions in the USA. At the same time, the modeling of schools after prisons can be connected to the ongoing criminalization of a wide range of everyday behaviors and the rise of the punishing state.

Moreover, oppressive economic, political, and cultural practices in the U.S. can be connected to other authoritarian societies that are following a comparable script of widespread repression. For instance, it is crucial to think about what racialized police violence in the United States has in common with violence waged by authoritarian states such as Egypt against Muslim protesters. This allows us to understand various social problems globally so as to make it easier to develop political formations that link such diverse social justice struggles across national borders. It also helps us to understand, name and make visible the diverse authoritarian policies and pedagogical practices that point to the parameters of a totalitarian society. This is especially true in addressing the ongoing criminalization of Blacks and the rise of new forms of domestic and state terrorism. As Nicholas Powers points out,

“The old racial line between ‘Black’ and ‘White’ has been redrawn as the line between criminal and citizen. Up and down the class hierarchy form poor to wealthy, Black people have to dodge violence, from macroaggressions to economic sabotage and from public shaming to physical attacks… every day another person of color is shot by police, and the hole left inside families are where love ones used to breathe. The cops not only steal the lives of our children; they steal the lives of everyone who loved them. A part of us freezes, goes numb.”8

Critical Thinking, Critical Culture

In this instance, making the political more pedagogical becomes central to any viable notion of politics. That is, if the ideals and practices of democratic governance are not to be lost, there is a need for progressives to address and accelerate the production of critical formative cultures that promote dialogue, debate and, what James Baldwin once called, a “certain daring, a certain independence of mind” capable of teaching “some people to think and in order to teach some people to think, you have to teach them to think about everything.”9 Thinking is dangerous, especially under the cloud of an impending neo-fascism, because it is a crucial requirement for constructing new political institutions that can both fight against the impending authoritarianism and imagine a society in which democracy is viewed no longer as a remnant of the past but rather as an ideal that is worthy of continuous struggle. This merging of education, critical thinking, and politics is necessary for creating informed agents willing to fight the systemic violence and domestic forms of repression that mark the authoritarian policies and repressive practices of the Trump administration.

Under the Trump presidency, the worse dimensions of a neoliberal order will be accelerated and will include: deregulating restrictions on corporate power, cutting taxes for the rich, expanding the military, privatizing public education, supressing civil liberties, waging a war against dissent, treating Black communities as war zones, and dismantling all public goods. Such actions make it all the more imperative for progressives to challenge a market-driven society that erodes the symbolic and affective bonds and loyalties that give meaning to social existence. Appealing to the economic interests of the public is important, but it is not enough. Hope has to be fed by the lessons of history, the recognition for collective action, and the willingness to “feel one’s way imaginatively into the situation of others.”10 Hope is not only about expanding the limits of the radical imagination, it is also about recognizing that resistance is a necessity that has to be rooted in a realistic assessment of the roadblocks ahead.

Refusing a politics of disconnection means taking on the crucial challenge of producing a critical formative culture along with corresponding institutions that promote a form of permanent criticism against all elements of oppression and unaccountable power. One important task of emancipation is to encourage educators, artists, workers, young people and others to use their skills in the service of a politics in which public values, trust and compassion can be used to chip away at neoliberalism’s celebration of self-interest, the ruthless accumulation of capital, the survival-of-the-fittest ethos and the financialization and market-driven corruption of the political system. Political responsibility is more than a challenge – it is the projection of a possibility in which new identification, affectations, and loyalties can be produced to enable and sustain new forms of civic action, political organizations, and transnational anti-capitalist movements. A radical democracy based on the best principles of a democratic socialism must be written back into the script of everyday life, and doing so demands overcoming the current crisis of memory, agency and politics by collectively struggling for a society in which matters of justice, equity and inclusion define what is possible.

Refusing a politics of disconnection means taking on the crucial challenge of producing a critical formative culture along with corresponding institutions that promote a form of permanent criticism against all elements of oppression and unaccountable power. One important task of emancipation is to encourage educators, artists, workers, young people and others to use their skills in the service of a politics in which public values, trust and compassion can be used to chip away at neoliberalism’s celebration of self-interest, the ruthless accumulation of capital, the survival-of-the-fittest ethos and the financialization and market-driven corruption of the political system. Political responsibility is more than a challenge – it is the projection of a possibility in which new identification, affectations, and loyalties can be produced to enable and sustain new forms of civic action, political organizations, and transnational anti-capitalist movements. A radical democracy based on the best principles of a democratic socialism must be written back into the script of everyday life, and doing so demands overcoming the current crisis of memory, agency and politics by collectively struggling for a society in which matters of justice, equity and inclusion define what is possible.

Neo-fascism thrives on the disparagement of others, nativism, ultra-nationalism, an appeal to violence, an unchecked individualism, and the legitimation of an alleged preferred people to dominate others. These are the elements of a formative culture rooted in nihilism, cynicism, economic insecurity, unrestrained anger, a paralyzing fear, and the collapse of public values and the ethical grammar that gives a democracy meaning. At work here is the undeniable fact of how education is at the center of politics, and can be used for either oppressive or emancipatory ends. This suggests strategies aimed at the development of alternative, progressive educational apparatuses, grounded in the pedagogical necessity to make knowledge and ideas meaningful in order to make them critical and transformative. This means appropriating and using the symbolic and intellectual tools of persuasion, identification, and belief as crucial political strategies. I am not talking about a facile appeal to a notion of consciousness raising. Rather, I am emphasizing the necessity for progressives to work in conjunction with labour unions, educational unions, and other social movements to develop the institutions necessary for a critical formative culture that can change the consciousness, desires, identities, investments, values, while providing a sense of agency of those who lack the tools of civic literacy and critical frames of reference necessary for understanding the conditions that produce misery, exploitation, exclusion, and mass resentment, all the while paving the way for right-wing populist movements.

Under the reign of casino capitalism, democratic public spheres along with the public they support are disappearing. One consequence is a warfare state built not only on the militarization of the economy but also on what my colleague Brad Evans calls “armed ignorance.” Such

ignorance represents more than a paucity of ethical and social responsibility, it is also symptomatic of an educational and spiritual crisis in the United States. A culture of fear, hate and bigotry has transformed American politics into a pathology. Fear cripples reason and makes it easier for authoritarian figures to engage in what might be called terror management. Trump’s speeches mobilized millions with the drug inducing appeal of uncertainty, fear, and hatred. David Dillard-Wright insightful commentary on Trump’s use of fear makes clear how he used it as both a political and pedagogical tool. He writes:

“The Trump rally speeches go through a litany of perceived threats to the American worker: the immigrants taking ‘our’ jobs, the terrorists who want to kill ‘us’, the media who want to silence ‘us’. Trump is no social psychologist, but he has an instinctive sense for crowds: the purpose of this rhetoric is to tear down the listener to a point of malleability, at which point, he ‘alone” supplies the answer (as in his ‘I alone can fix it’ speech at the Republican National Convention in the summer). He drowns the listener in fear and then reaches out a helping hand from the threat that he, himself, has conjured. This verbal waterboarding breaks down the Trump fan into a panicked rage and then channels that fear and anger into the pretend solution of a giant wall or jailing Hillary Clinton, which not incidentally, also places Trump at the center of power and control over his fans’ lives. Fear actually short-circuits rational thought and gets the rally-goer to accept the strongman as the only way to avoid the perceived threat.”11

The appeal to mass produced fear legitimates a politics that tramples the rights of minorities, young people, and dissidents. Moreover, it reinforces a violent and corrupt lawlessness that extends from the highest reaches of government and big corporations to the para-militarization of our schools and police forces. Domestic terrorism becomes normalized as unarmed Blacks are killed by the police almost weekly, while more and more members of the population are considered excess, disposable, redundant, and subject to the bigotry of escalating right-wing groups, corrupt politicians, and policies that benefit the financial elite. And with the election of Donald Trump to the Presidency, a fog of authoritarianism will all but diminish any vestige of democracy and civic literacy. Such a prophecy is not simply the stuff of science fiction. As David Remnick predicts the Trump administration will usher in both a withering of public values and a democratic sensibility leading to a dystopian social order immersed in misery, violence, and cruelty:

“There are, inevitably, miseries to come: an increasingly reactionary Supreme Court; an emboldened right-wing Congress; a President whose disdain for women and minorities, civil liberties and scientific fact, to say nothing of simple decency, has been repeatedly demonstrated. Trump is vulgarity unbounded, a knowledge-free national leader who will not only set markets tumbling but will strike fear into the hearts of the vulnerable, the weak, and, above all, the many varieties of Other whom he has so deeply insulted. The African-American Other. The Hispanic Other. The female Other. The Jewish and Muslim Other. The most hopeful way to look at this grievous event – and it’s a stretch – is that this election and the years to follow will be a test of the strength, or the fragility, of American institutions. It will be a test of our seriousness and resolve.”12

The world is on the brink of nuclear war, ecological extinction, an accelerating refugee crisis, and a growing culture saturated in violence; yet, the public is persuaded that the burning issues of the day focus on the breakup of Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, Kim Kardashian’s loss of $11-million in jewelry to thieves, or the endless focus on the banality of Reality TV and celebrity culture. In addition, violence is now treated as a theatrical performance paving the way each day for the next news cycle operating primarily as spectacle and entertainment. Moral and political hysteria is in fashion and has undermined the public spheres that promote self-reflection, dialogue, and informed judgment. Informed exchanges and arguments that rely on evidence have been displaced by a culture of shouting, emotion, lying, and thuggery. War comes in many forms and is as powerful as a form of ideology and identification as it is in the service of multiple forms of violence. Once we recognize the metrics of war as both crisis of politics and education, we can mobilize against both its ideological and material relations of power. But time is running out.

New Discourse, New Politics

The American public needs a new discourse to resuscitate historical memories and develop new methods of opposition in order to address the connections between the escalating destabilization of the Earth’s biosphere, impoverishment, inequality, police violence, mass incarceration, corporate crime, and the poisoning of low-income communities. Once again, not only are social movements from below needed, there is also a need to merge diverse single-issue movements that range from calls for racial justice to calls for economic fairness. Of course, there are significant examples of this in the Black Lives Matter movement and the ongoing strikes by workers for a living wage.13 But these are only the beginning of what is needed to contest state violence, institutionalized racism, and the savage machinery of neoliberal capitalism.

There has never been a more pressing time to rethink the meaning of politics, justice, struggle, collective action, and the development of new political parties and social movements. The ongoing violence against Black youth, the impending ecological crisis, the use of prisons to warehouse people who represent social problems, the poisoning of children due to neoliberal fiscal policies, and the ongoing war on women’s reproductive rights, among other crises, demand a new language for developing modes of creative long-term struggle, a wider understanding of politics, and a new urgency to create modes of collective struggles rooted in more enduring and unified political formations.

Such struggles demand an increasingly broad-based commitment to a new kind of activism. We don’t need tepid calls for repairing the system; instead, we need to invent a new system from the ashes of one that is terminally broken. We don’t need calls for moral uplift or personal responsibility. We need calls for economic, political, gender, and racial justice. Such a politics must be rooted in particular demands, be open to direct action, and take seriously strategies designed to both educate a wider public and mobilize them to seize power.

Trump’s willingness to rely upon openly fascist elements prefigures the emergence of an American style mode of authoritarianism that threatens to further foreclose venues for social justice and civil rights. The need for resistance has become urgent. The struggle is not simply over specific institutions such as higher education or so-called democratic procedures such as the validity of elections but over what it means to get to the root of the problems facing the United States. At the heart of such a movement is the need to draw more people into subversive actions modeled after the militancy of the labour strikes of the 1930s, the civil rights movements of the 1950s and the struggle for participatory democracy by the New Left in the 1960s while building upon the strategies and successes of the more recent movements for economic, social and environmental justice such as Black Lives Matter and Our Revolution. At the same time, there is a need to reclaim the radical imagination and to infuse it with a spirited battle for an independent politics that regards a radical democracy as part of a never-ending struggle.

“We need a language that reframes our activist politics as a creative act that responds to the promises and possibilities of a radical democracy.”

None of this can happen unless progressives understand education as a political and moral practice crucial to creating new forms of agency, mobilizing a desire for change and providing a language that underwrites the capacity to think, speak and act so as to challenge the sexist, racist, economic and political grammars of suffering produced by the new authoritarianism. The left needs a language of critique that enables people to ask questions that appear unspeakable within the existing vocabularies of oppression. We also need a language of hope that is firmly aware of the ideological and structural obstacles that are undermining democracy. We need a language that reframes our activist politics as a creative act that responds to the promises and possibilities of a radical democracy.

Broad-based social movements cannot materialize overnight. They require educated agents who are able to connect structural conditions of oppression to the oppressive cultural apparatuses that legitimate, persuade, and shape individual and collective attitudes in the service of oppressive ideas and values. No wide-ranging social movement can develop without educating a public about the diverse economic, political, cultural, and pedagogical conditions that provide a discourse of critique and inquiry on the one hand and a vocabulary of action and hope on the other. Under such conditions, radical ideas can be connected to action once diverse groups recognize the need to take control of the political, economic, and cultural conditions which shape their world views, exploit their labour, control their communities, appropriate their resources, and undermine their dignity and lives. Yet, raising consciousness alone will not change authoritarian societies. Though, it does provide the foundation for making oppression visible and for developing from below what Etienne Balibar calls “practices of resistance and solidarity.”14 We need more than radical critique of capitalism, racism, and other forms of oppression. Any viable struggle for justice and a radical democracy also need to nourish a critical formative culture and cultural politics that inspires, energizes, and provides a radical education project in the service of a broad-based movement for democratic socialism. •