To draw the net from the water together

while singing a song in unison,

to forge together the iron fine like lace,

to be able together to cultivate the land,

to be able to eat the honeyed figs together,

to be able to say: “all together in everything,

save the cheek of the beloved”…

Nâzım Hikmet

From the poem “The Legend of Sheikh Bedreddin” (1936)

The press reports that during a visit to Western Thrace, where a sizeable Turkish minority lives, Alexis Tsipras, the Greek Prime Minister, evoked the name of Sheikh Bedreddin, praised him and said that he should be a source of inspiration for all of us today. So, who is this Muslim sheikh whom a nominally leftist Greek Prime Minister, avowedly atheist, recommends as a source of inspiration to all Greeks, irrespective of their religion? A most ticklish remark at first sight. We should be thankful to Tsipras for having raised the topic, hastening to add that he personally, given his record in office, is absolutely unfit for inspiration by the grand old man.

Sheikh Bedreddin (1359–1420) lived in the second half of the 14th and the first two decades of the 15th centuries, the latter period being one in which the fortunes of the rising Ottoman state came to a temporary halt under the impact of the Ankara war of 1402, in which the armies of Tamerlane, the Mongol nomadic emperor, routed the Ottomans. The next decade and a half saw civil war between the different contenders to the throne raging on the territory of the Ottoman state in Asia Minor and the Balkans. Bedreddin’s deeds of historic importance had this civil war as their background.

His life is a web of contradictions. He was both a fakih, i.e. a scholar of Islamic jurisprudence, one of the best ever even by

the admission of his ideological opponents, and a sufi, one who lives religion more according to its inner meaning than

according to outward rules. He spent long years in Cairo, the major learning centre of the epoch, and was converted to Sufism by a

certain Shikh Ahlati. He was never the same man again after that conversion. He visited Khorasan and Aleppo and finally returned home to Ottoman territory.

But make no mistake. Bedreddin, despite his Muslim credentials was half-Greek from his mother’s side, allegedly converted to Islam

when she married Bedreddin’s Turkish father. Their son was born in Dimoteka (Greek: Didymóteicho) in 1359 and died in Serez (Greek: Serres) in 1420, both localities being Greek territory today, but were under

Ottoman rule back then. So it is a great shame that this great man of Greek descent as well as Turkish has not been sufficiently cherished

jointly by our two nations in a manner that befits his legacy. For he himself was not only a communist, but an internationalist as well.

A Communist Revolutionary

This, of course, is the pinnacle of the web of contradictions that form Bedreddin’s life. This man of high religious standing, who had been

given a hand by his sheikh, Ahlati, as the latter was dying and was therefore the sheikh of a religious order, was also a communist. He

and his disciples, among whom Börklüce Mustafa, an illiterate Turkish peasant from the Aegean region of Anatolia right across the

island of Chios and a Jewish convert, Torlak Kemal, from a region slightly more to the northeast, but still in the Aegean region,

defended common property in the means of production, land and farm buildings and beasts of burden and agricultural implements. Their

programme is sometimes misinterpreted as the “distribution of land.” No, it is common property, abolishing all private holdings.

The other aspect of their programme is internationalism. Of course, at that time different ethnic groups were more commonly identified by their respective religion. Bedreddin and his disciples stood for the unity and fraternity of all religions, Muslim, Christian and Jewish

alike. It is a well-established historical fact that Bedreddin, during one of his multiple visits to the Aegean region of Anatolia, crossed over, in company of Börklüce Mustafa, to the Greek island of Chios to have long talks with the local notables of the Orthodox

church there and with ordinary peasants, which no doubt was part of their preparations for an uprising. In fact, some evidence exists to

suggest that the influence of the Bedreddin movement extended all the way from Enez (Greek: Ainos) in continental Eastern Thrace (today part of Turkey) to Crete, evidence that is worthwhile to pursue by historians from both Greece and Turkey.

How is it that a theologian became a revolutionary internationalist communist? How, in particular, did his very advanced conception of common property emerge? And how did a religious order act like a revolutionary organization? I have explored all these questions in an

article published at the beginning of this year to commemorate the 600th anniversary of Bedreddin’s revolutionary uprising against the Ottoman state. I cannot go into the details of the answers to all these questions. Suffice it to say that Bedreddin was a materialist

in disguise, that common property in the means of production was not exceptional among the dervishes of the period, leading to the formation of farmsteads that functioned on what can only be depicted as communistic principles, and that religious orders were, as a rule,

class organizations.1

6th Centenary of the Revolution of 1416

When that revolution erupted in 1416, it was far from being local as many jacqueries are. It extended across a vast geographical area from the Turkish Aegean and Chios all the way to Deliorman (Bulgarian: Ludogorie) in Bulgaria at present and Serez (Serres) in Greece, both in Western Thrace. There were three uprisings at least, with tentative evidence of other centres of insurrection. Börklüce and his ten thousand combatants, Turkish and Anatolian Greek landless peasants, Turkoman nomads and Greek islander seafarers, routed the Ottoman army twice before being defeated in the end at the hands of a huge army. Börklüce himself was crucified on the back of a camel, no doubt to

affront the synchretic nature of the religious faith of the Bedreddin order. The second insurrection was that led around Manisa by Torlak Kemal, which also ended in a debacle.

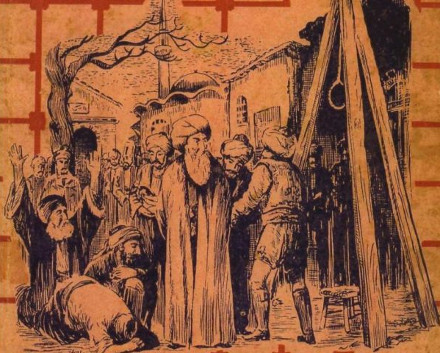

Perhaps the most massive participation was in the third insurrection, this one led by Bedreddin himself. He had been kept under forced residence in the Marmara region and, having eloped, he moved to Deliorman in what is Bulgarian territory today and roused the masses to

insurgency. The insurrection spread like wildfire. However, the more shaky allies within the revolutionary camp secretly made a pact with

the Sultan and betrayed the cause. Bedreddin was abducted and taken to the Sultan’s court where he was tried and convicted to death. He was hanged in the marketplace of Serez (Serres) on 18 December 1420.

This is the 600th anniversary of that great internationalist communist revolution. Obviously the revolution came before conditions were mature for communism. It was bound to fail, if not before taking power, then after it. However, that it should have erupted in a geography that

now harbours the two nations of Greece and Turkey is a great honour for us. We will strive on both sides of the Aegean to create the conditions of such an internationalist revolution once again within the framework this time of 21st century capitalism, much more favourable to the rise of the working class to power and the building of a classless society. •