On December 9, Parliament voted in favor of a presidential impeachment by 234 votes to 56, with 7 invalid votes and 2 abstentions. Over 30,000 protesters were present to celebrate the impeachment. The votes in favor of impeachment exceeded what was expected, though it was slightly lower than the 81 per cent support for impeachment among public opinion.

In spite of mounting pressure since late October to step down, President Park Geun-hye has refused to resign, instead searching for a political solution that involved neither resigning nor impeachment. However, every maneuver to retain the presidency failed and her presidency ceased functioning.

In spite of mounting pressure since late October to step down, President Park Geun-hye has refused to resign, instead searching for a political solution that involved neither resigning nor impeachment. However, every maneuver to retain the presidency failed and her presidency ceased functioning.

A series of ever-growing million-strong protests forced parliamentarians to finalize the impeachment process. The 2.3 million mega-protest on December 3rd was a critical turning point that halted Park’s last attempt to escape impeachment.

South Koreans were angry not just with the ruling Saenuri Party, but also opposition parties, which oscillated, without any plan or determination, at every turn of Park’s so-called apology speeches. The huge mobilizations on each weekend of November up to last Saturday’s mega-protest maintained increasing pressure on the mainstream political parties, both those in power and in opposition.

The Biggest Political Scandal Ever

This historic battle began as a dispute between the Blue House (presidential palace) and the conservative Daily Chosun, whose concerns as a loyal opposition was despised by Park and her lackeys. Investigative journalists exposed a series of shocking revelations of Choi Soon-sil‘s various power abuses and extortion of public funds under Park’s connivance or cooperation, as well as personal amoral behavior.

The prosecution arrested Choi and her accomplices; personal business agents like Cha Eun-taek, a music video director, and Jang Shi-ho, her nephew; presidential secretaries like Ahn Jongbeom and Jeong Hoseong; government high officials like Kim Jong, former Deputy Minister of Culture and Sport Department, and others.

Using her 40 year-long friendship with Park, Choi wielded enormous power following Park’s election as President in 2013. The most shocking news was that she revised Park’s speeches, which was exposed by JTBC’s report based on Choi’s tablet PC. Choi was also deeply involved in establishing two foundations, Mir Foundation and K Sprot Foundation, which were founded with millions of dollars allegedly donated by major Chaebols, that is, Samsung, Hyundai, SK, Lotte, and so on. In fact, these mysterious foundations were used as a conduit for financial extortion and money laundry.

In addition, Jung Yura, Cho’s daughter, enjoyed illegitimate privileges such as financial help from the National Horseriding Association and admission to Ewha Women’s University through irregular procedures. Choi commanded Cha and Jang as her business agents in securing government contracts related with sport and culture spheres.

Choi’s hidden power and privilege worked like magic, wielding hundreds of millions of dollars in the budgets, through her private paper companies in Korea and Germany. This little-known woman was a key player behind the president. When this mystery was finally solved, Pandora’s box of truth was open.

Park Versus Party Politics

The crisis of Park’s regime could be foreseen. In the general election of last April, the ruling Saenuri Party suffered a huge defeat, losing its majority. Several dissidents who were expelled from the ruling party won seats and opposition parties won a majority in spite of splits. Thus, though the defeat was caused by arrogant abuses of the pro-Park faction and unfair selection of candidates, the pro-Park faction held onto leadership of the pary, defying popular opinion.

Lee Jeongheyon took the leadership due to his obstinate loyalty to the president, and his improper remakes were widely ridiculed, thus the Saenuri Party was seriously stricken with crisis. As the Choi-Park scandal exposed, the party was divided along factional line. The minority non-Park faction joined the opposition in criticizing the scandals and the president. The majority pro-Park faction was isolated, and desperate acts by some MPs to defend the president invoked a huge backlash of popular anger.

The opposition parties, the Democratic Party (DP) and People’s Party (PP), had a majority in parliament, but its initial response to the scandals were rather half-hearted, trailing behind media and public opinion. They could not propose any proper measures to cope with the crisis, wavering between a resolute struggle and a political compromise. At this initial stage, the opposition was rather reluctant to initiate an impeachment because they had no confidence in their capacity to secure a two-third majority.

Though they joined candle light protests, the opposition opportunistically kept some distance from the extra-parliamentary mobilization as they regarded it as their task to pursue a solution within parliament. However, throughout the whole November, mobilization kept on growing on a massive scale beyond their expectation, so much so that the opposition had no other option but to follow popular opinion and initiate the impeachment procedure.

In face of tremendous protests, Park made the final maneuver in her last speech on November 29. Though she mentioned her intention to step down for the first time, she proposed that parliament decide on how she should resign, without mentioning any details. This move was interpreted as a maneuver to evade impeachment. A section of the non-Park faction welcomed her proposal, and decided not to join the impeachment, on the condition that the president clarify the precise date of resignation.

However, the mega-protest of December 3 clearly expressed the will of the indignant people: the immediate, unconditional resignation of the president. Under mounting pressure, the dissidents of the ruling party gave up on a political solution based on compromise and joined the opposition to support impeachment. Thus, it was not the non-Park faction, but the pro-Park faction that exposed in the public eye, and the path to the impeachment was clearly paved.

Media’s Role and the Limit of its Hegemony

In this historic battle, the media, especially the conservative media, played a key role, in that every day from late October till now, the media exposed a vast range of power abuse, bribery, and irregularities. Countless unjustified, illegal and illegitimate acts by Park and Choi and their accomplices were reported on a daily basis. Some of the cable TV networks dealt with the scandals around the clock.

In essence, the mass media in South Korea is largely privately owned by conservative media mogul or strongly linked to big businesses. Thus, on the whole, conservative newspapers and cable TV networks supported Park and her conservative government. Some of them were vulgar outlets of anti-communist, anti-North Korea rightwing extremists.

On the other hand, progressive or liberal media are smaller in size and their influence is rather limited. Hangyeoreh Shinmoon and Daily Gyeonghyang criticized the government, but among the TV networks, JTBC, though linked with Samsung, was regarded as the only anti-government media, under the influence of Sohn Seokhee who moved from the government-controlled MBC.

In this crisis, JTBC’s exposure of Choi Soon-sil’s tablet PC on October 24 was the decisive trigger of a whole series of political crises, though TV Chosun prepared for systematic attack through a more extensive coverage of the scandals. The balanced reports and democratic approach of JTBC boosted its credibility and popularity beyond that of pro-government broadcasts KBS and MBC, or other TV networks.

In a barrage of scandal exposures, the media as a whole, whether conservative, liberal or progressive, were united in criticizing the corrupt government, even competing among themselves on this issue. On the whole, extensive media coverage led to a tremendous explosion of anger and indignation, and ultimately to unprecedented mega-protests.

However, the media was shocked at the enormous scale of the mobilization and used their influence to curb the power of the candle light protests. The media preached non-violence, constantly emphasizing the difference between the candle protests and the social movement’s confrontational approach. Seemingly, the hegemony of the conservative media worked and the candle light protests, though growing to a size beyond its control, remained peaceful and civil.

December 3 was a watershed. After Park’s speech, conservative media began to advocate a political solution within the framework of law and order, without directly attacking the candle light mobilization. More and more voices from extreme rightwing pundits were audible. However, the sheer size of the December 3 mobilizations overwhelmed any maneuver of the conservative media, which in turn leaned toward the inevitability of presidential impeachment.

The dialectical, dynamic interaction between media and mass mobilization was the key factor in determining the political path of this crisis. Initially, the media seemed to dominate, but the ever-growing candle light protests persisted and eventually prevailed, pushing through the course of the historic struggle.

The Evolution of the Candle Light Protests

Though the media exposures were shocking, the protest began as usual: a candle light vigil at the Cheonggye Square, a historical site of protest. On the first weekend after the JTBC’s revelation, 30,000 people gathered to criticize the president and demanding her resignation.

With daily media coverage of the scandals, popular anger exploded, and anger at Park’s speech on November 4 led to 200,000 people joining the candle light protest on November 5, a sign of the beginning of mega-protests. On November 12, a one million strong mega-protest signified an escalation of popular protest. The scale of spontaneous mobilization was highly explosive, breaking records at subsequent weekend rallies as follows:

October 29: 30,000

November 5: 200,000

November 12: 1,000,000

November 19: 1,900,000

November 26: 1,500,000

December 3: 2,320,000

The candle light protests came to dominate politics. The president’s untruthful excuses and even more exposures provoked bigger mobilization on November 19 and 26. Mobilization of millions became a norm. Park’s speech on November 29 provoked the largest mobilization in South Korean history. However, reaction was never docile. The police attempted to put a strict limit on protest marches. The police set up lengthy walls of buses as a blockade around the rally spot, and did not allow anyone to approach the Blue House.

However, a court decision defied police bigotry. Repeatedly, the court decided that the duty of the police is to protect citizens that were marching, not stop them. Thus, in each rally candle light marchers could walk nearer and nearer toward the Blue House, and on December 3, people marched up to the 100 meter parameter around the Blue House.

And in an effort to curtail the candle light protests, the police publicized a severely reduced number of rally participants, denying the obvious fact that millions had joined the rallies. However, media cast doubts on the calculating method using by the police and confirmed the authenticity of the protest’s numbers based on alternative, scientific method.

In face of huge mobilization, pro-Park reactionary groups attempted counter-mobilizations. On the weekend, counter rallies were organized, but their sizes never went beyond several thousand. Even these meager rallies were packed with old people who were paid to join the rallies.

Candles in the Historical Context

Historically, after World War II, Korea was liberated from Japanese imperialism, but divided by Cold War politics, and suffered from a bloody hot war. After three year war, Korea was permanently divided and South Korea was incorporated into the U.S.-led capitalist world system, and politically dominated by anti-communist dictatorships: Rhe Shingman (1948-1960), Park Chunghee (1960-1979) and Chun Doohwan (1980-87).

The popular struggle for democracy led to the April Revolution of 1960, and enjoyed a short freedom in 1980 Democracy’s Spring, but it constantly faced harsh, until the June Uprising and partial victory in 1987. Since then, South Korea has been regarded as a formal democracy, but under conservative rule, because the June Uprising could not overthrow the military dictatorship completely.

Under the auspices of the IMF crisis, regime change was made possible and the democratization process moved slightly forward under the 10-year liberal regime of Kim Daejung (1997-2002) and Rho Moo-hyun (2003-2007), but unfortunately combined with a neoliberal turn. After a ‘lost decade’, conservative forces returned to power with Lee Myeongbak (2008-12), and Park Geun-hye (2013-present).

The present conservative rule was made possible by the economic downturn and poor performance of the liberals. Old generations’ nostalgia of powerful leaders drove Park’s popularity upward, in spite of her anti-people, neoliberal policies.

The 2016 candle light protest can be seen as the historic continuation of the June Uprising of 1987, when students and citizens fought street battles for three weeks, winning a victory in spite of tear gas and massive arrests. The 1987 uprising paved the way for democracy, but the subsequent process failed to deepen democracy. In a sense, Park’s government was a reactionary attempt to revive the ghost of the development dictatorship of Park Chunghee.

The 2016 candle light protests have decisively buried the remnants of the dictatorship and provide a more solid foundation for democracy in every sphere of the society. It has again proven that the real motor of history is people power in streets and squares, not institutional politics.

Social Movements and Candle Protest

Social movements in Korea made huge contributions to democratization and social justice. But after ups and downs, as well as constant repression by regimes, two pillars of historical social movements, that is, the student movement and trade union movement, lost their strength.

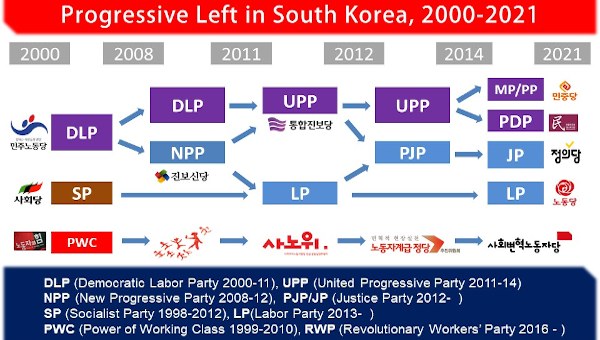

Of course, in the course of democratization, social movements expanded their area of influence in society and advocated many progressive reforms. However, the historic effort to build a progressive political party failed, even if the Progressive Justice Party (PJP) survived as a minor party in the parliament. The United Progressive Party (UPP) was dissolved in 2014 as a result of the Park government’s outrageous attack and its own political mistakes.

The candle light vigils are a comparatively new phenomenon that began as a means to protest in 2002, when two middle school girls were trampled to death by a U.S. military tank. The 2002 candle protests were a key moment in the anti-U.S., anti-imperialist mass struggle.

In 2008, shortly after the Lee MB government was inaugurated, young school girls began protesting against the new government’s decision to import U.S. beef without proper supervision. The 2008 candle light protests were different from the previous one, in that the protesters mobilized through the online community, a virtual square where discussion and debates proliferated.

The candle light protests showed a unique dynamic that had not been seen before. All of the different groups, mostly organized via online communities, from young students to housewives, joined candle light vigils and marches. The newly emerging protesters were free of old rules, and freer, more expressive, more diverse and more imaginative. Within this free and diverse environment, more militant action groups emerged and led militant street battles against police brutalities.

The 2008 candle light protest waged a daily 4-month-long struggle. Its climax was a one million strong rally on the anniversary of the June 10, 1987 Uprising. On August 15, the last big rally was held, but thereafter, under severe repression, the candle light protest dwindled as a movement.

However, the 2008 candle light protests raised the issue of democracy under the slogan of Constitution Clause 1: The R.O.K. is a democratic republic and its power comes from the people. Taking the beef issue as its starting point, the protest challenged the authoritarianism of Lee’s conservative government.

Compared with 2008, the 2016 protest had a more expanded mass base, and the scale of mass mobilization became even larger, though the intensity of struggle or radicalization was lower. Thus, with its determination and enormous scale of mobilization, the 2016 candle light protests won a decisive victory over the whole establishment, unlike the 2008 protest’s eventual defeat.

In 2008, the social movement and trade unions were perplexed with the emergence of a new, different type of protests and movements. In contrast, in 2016, they were not in conflict with rank-and-file candle carriers. This was an essential strength of the candle protests, defeating divisive maneuvering and ideological attacks.

Formally, the weekend mega rallies were led by a newly formed coalition, the Emergency People’s Action, comprised of 1,500 civil society organizations. However, spontaneity overwhelmed the organized sectors. For instance, on November 30, the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU) organized a general strike in which 200,000 workers joined, and held a 100,000 strong rallies and march nationwide. Usually, this would have been seen as a huge mobilization, but in the context of candle light protest, organized labour’s intervention had a relatively small impact.

The 2016 candle light protest became too big to control. No group or forces could control or dominate it. In some respect, it is a perfect example of collective intellect.

Beyond the Impeachment

The turning point was the mega-protest on December 3. Before it the conservative media had prevailed and wielded ideological hegemony. The media agitated for protest and applauded its decency in avoiding the violent confrontational approach of old social movements. After Park’s speech on November 29, the conservative media preferred a compromise, based not on impeachment, but on an orderly retreat, in which rival factions within the ruling party united.

However, millions of candles demanded her immediate resignation and refused any compromise, thus making parliamentary impeachment the only path to a solution, as long as Park refuses to step down. As opposition parties united and were joined by the non-Park faction of the ruling party, the path to impeachment was cleared.

It is said that Park gave up attempting another maneuver to defend herself and chose to wait for impeachment, still with the slim hope that impeachment would be voted down. The pressure was on the pro-Park faction MPs who were trapped between Park and their own electorates. Voting for impeachment would mean a punishment of the president, and a self-punishment of their own party. Voting against impeachment would mean no future career as a politician, as well as triggering an even larger protest against the regime as a whole, or apocalyptic catastrophe.

Eventually, the ever-growing candle light grassroots prevailed over the media and institutional party politics. A long road to democracy was paved by the power of multi-million mega-protests.

South Koreans were given the right to vote under a U.S. military government. Historically, South Korea had no Chartist or Suffragette movement. However, in 1987, they fought for the right to elect a leader directly, and now in 2016, they exercised the right to recall a wrongly chosen leader. Technically, the ouster of Park from power is an impeachment by the parliament, but in realty it is a recall enacted by people power.

The 2016 candle light uprising has won a tremendous historical victory and democracy will be even stronger and more extensive. However, the people power of candle light protests must go beyond impeachment. It is time to start an imaginative experiment of revolutionizing the potential of people power. The candles may go out, but could be rekindled at any time. In this sense, the candles won’t die out. •

This article first published on the Links website.