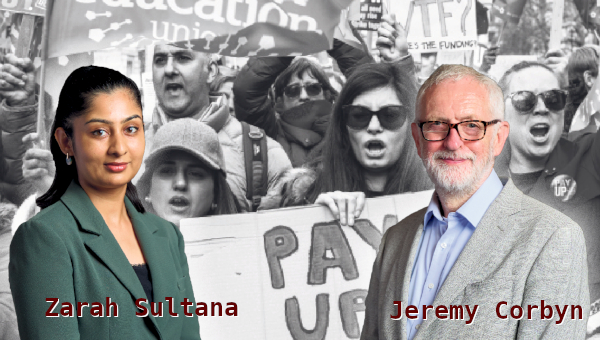

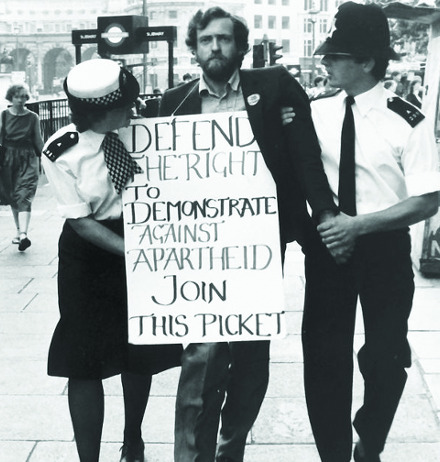

Who would have thought? Britain, of all places – that island so often lamented to be devoid of revolutionary history and thought, the land of Fabianism without Marxism, the home of Thatcher and Blair and the City – now has one of the most radical leaderships of a major social democratic party in the advanced capitalist world. The election of Jeremy Corbyn to the leadership of the British Labour Party is an expression of enormous discontent and anger at ever-worsening conditions since the crisis of 2008. Very few anticipated anything approaching Corbyn’s victory at the beginning of the race, not least Corbyn himself. But now, with the benefit of hindsight, it is possible to identify the confluence of tendencies that led to this perfect storm in the summer of 2015 – and an analysis of the history of the Labour Party can illuminate situations and strategies for the British left in the coming years.

While its historical memory has been obscured by the successive dominance of Thatcherism and Blairism, Britain had a vibrant left in the 1970s, with a strike rate that was among the highest in Europe. High levels of labour militancy and other forms of extraparliamentary mobilizations also strengthened socialists within the Labour Party; its strength within the party as a whole is manifested in the party program in 1973, which called for nationalization of the 25 largest companies in Britain, as well as the election manifesto in 1974 that publicly proclaimed its goal to “bring about a fundamental and irreversible shift in the balance of power and wealth in favor of working people.”

While its historical memory has been obscured by the successive dominance of Thatcherism and Blairism, Britain had a vibrant left in the 1970s, with a strike rate that was among the highest in Europe. High levels of labour militancy and other forms of extraparliamentary mobilizations also strengthened socialists within the Labour Party; its strength within the party as a whole is manifested in the party program in 1973, which called for nationalization of the 25 largest companies in Britain, as well as the election manifesto in 1974 that publicly proclaimed its goal to “bring about a fundamental and irreversible shift in the balance of power and wealth in favor of working people.”

The Contradictions of Blairism and

the Rise of Corbyn

The Labour left, with Tony Benn as a leading figure, developed the Alternative Economic Strategy as a left solution to the stagflationary crisis, based on extensive public ownership and industrial democracy, as well as reflation buffered by capital control. Much of the party establishment, especially the parliamentary party, neither supported economic policies proposed by the left, nor even had any plans to carry out these platforms adopted by the party itself; however, the left gained power in local parties and some key unions, which gave them greater powers at Annual Conference and the National Executive Committee (NEC) of the party. In the end, though, the left’s influence in the party hardly translated into actual power at the parliamentary and governmental level. Even though the Labour Party was in government for 11 out of 15 years in the period between 1964–79, with high levels of labour militancy, the Labour government by Wilson and Callaghan was profoundly reluctant to take any leftward path; facing the crisis of profitability and inflation, the Labour government opted to resolve the crisis mainly through voluntary income restraint from the union leadership and the “proto-neoliberal” fiscal policy of retrenchment after 1976.

Faced with a Labour government drastically at odds with politics of the activist base, the latter channeled its energy toward the movement for intra-party democratization, which they saw as a necessary precondition for socialist transformation. The Campaign for Labour Party Democracy (CLPD) was established in 1973, and gained momentum as the Labour government began to increasingly alienate and disillusion the base. In 1981, the CLPD activists succeeded in winning one of its key demands, electoral reform for the party leadership race. Previously, party leaders had been elected solely by the Members of Parliament (MPs); under the new system, MPs retained only 30 per cent of the votes, while an equal proportion was allocated to local party activists in the Constituency Labour Parties (CLPs) and unions gained 40 per cent. Among the three sections of the party, the CLPs were the bastion of the Left. In the 1981 Deputy Leadership election, in which Tony Benn stood against Denis Healey on the right, more than 80 per cent of the CLPs’ votes went to Benn, while the clear majority of MPs and the union leadership voted for Healey, giving him the narrowest of victories. Crucially, however, the CLPs were not only a left voting bloc, but also active political communities. They were not mere electoral machines; they also organized solidarity demonstrations and socialist political education.

The ascendency of the Labour Left came to a major halt in 1981, when the party establishment was able to successfully use the severe electoral defeat in 1983 under the left-leaning leader Michael Foot – in large part caused by the defection of the right that formed the new Social Democratic Party (SDP) – to go on the offensive against the left in the name of electability. Neil Kinnock, the new party leader elected in 1983, was the perfect figure to commence a long offensive against the left, as he came from the so-called “soft left” wing of the party. The strategy involved both repression of left activists and weakening of CLPs institutionally. Numerous activists were stripped of parliamentary candidacy, suspended from the party, or expelled outright, for taking positions such as refusing to collect the Thatcherite poll tax, opposing the Gulf War, and criticizing the party leadership as racist (the party executive condemned the Black Section as “divisive and contrary to the central principles of the Party”).[1] At the same time as the Kinnock leadership was pursuing these “witch-hunts,” they were also pushing for stripping the CLPs of voting rights that they had gained in 1981; instead of the local CLPs debating and deciding on their vote at party meetings, where substantive deliberations could take place, what they proposed as “One Member One Vote” (OMOV) would instead give a postal ballot to each party member. It was thought, both by the proponents and the opponents of OMOV, that removing the power concentrated among the activists would strengthen the power of those with resources and means of mass communication, namely the party leadership and the mass media. OMOV also enabled the leadership to turn the rhetoric of democratization against the left, blasting them for seeking to concentrate power among those “unrepresentative” radical CLP activists. OMOV for the CLP votes in leadership elections was finally introduced in 1993.

By the time Tony Blair rose to party leadership in 1994, even the CLPs had become much less threatening to the party establishment, due to the combined effects of expulsion and resignation. Blairism was able to establish absolute dominance in the party by successfully disorganizing and obliterating all viable intra-party alternatives; this was the most crucial factor that rendered TINA (“There Is No Alternative”) a reality, leading Thatcher to claim that her biggest political achievement was to have changed the Labour Party.

However, Blairism was not able to build an active, mass social base supporting it, hence lacking real hegemony. Blair sought to create what political scientist Meg Russell aptly called a “massive but passive” membership[2]; those who pay party dues and possibly canvass during election campaigns, but otherwise are not active in the party, and hence do not pose an internal threat to the leadership. Such passive membership is indeed congruent with the strategy described by political scientist Anthony Downs – he argued that political parties had the sole, uncontested aim of maximizing their electoral success, and that parties would only seek to chase voters with exogenously-determined preferences that they cannot change.[3] Blair perfected such Downsian politics – chasing the voters in the middle, as indicated by the latest polls and focus groups, to prioritize above all else the maximization of short-term electoral chances. But the “massive and passive” formula began to collapse after the election euphoria of 1997. The remaining members were passive enough not to threaten Blairite rule itself, but its support was tepid and conditional, and further significantly undermined by the Iraq War; indeed, as early as in 1998, the left slate Grassroots Alliance won the majority of the members’ votes for the National Executive Committee. The state of membership was worse. Once the Tories were gone, there was little to remain enthusiastic about the political creed whose main self-justification was its ability to win elections. Predictably, the membership itself began to precipitously decline after 1997, halving in less than a decade.

Such trends began to alarm even the New Labour leadership, which after all depended on the free campaigning labour of members. Ed Miliband’s leadership – which represents a partial repudiation of Blairism, while remaining firmly within the confines of New Labour – introduced the “Refounding Labour” initiative in 2011, in the name of further democratization of the party. The rhetoric of Refounding Labour is quite striking, in its attempt to absorb the left critique of New Labour. It sought to begin by amending Clause I of the Party Constitution, shifting the party’s stated purpose away from a parliamentary-centric one. Now we are told that Labour’s goal is “to bring together members and supporters who share its values to develop policies, make communities stronger through collective action and support, and promote the election of Labour representatives at all levels of the democratic process.” Such a symbolic repudiation of the purely electoralist and parliamentarist conceptions of a political party was accompanied by creation of the “Supporters’ Network,” which involves growing a network of non-member “supporters” who would help in campaigns but without rights as members.

The reform of leadership elections in 2014 can be seen as an extension and culmination of the process begun with Refounding Labour. With the pretext of a manufactured allegation around Unite’s scheme to “rig” parliamentary selection process in Falkirk, the party’s Collins Review proposed the introduction of a pure OMOV system for leadership elections, eliminating both the votes of unions and MPs, as well as the extension of franchise to the “registered supporters” who paid £3 fee. The change was primarily driven by the desire to reduce union influence, as unions have recently become significant left forces in the party; but MPs’ special votes were also removed alongside the unions’, to bolster the claim of democratization. To the extent that New Labour still commanded popular support, such measures of “democratization” would have strengthened the party’s capacity without threatening the existing power structure. No one had the slightest concern that the pursuit of OMOV to its logical conclusion could actually open up a danger that the left could take power; after all, whatever the widespread discontent with New Labour, in 2010 the left leadership candidate Diane Abbott won only 7.4 per cent of the party members’ votes and finished last among the five candidates. However, deepening austerity measures by the Coalition government since 2010, and the rise of radical anti-austerity movements in the wake of the economic crisis since 2008 – the student movement of 2010, mass public-sector strikes in 2011, and the Scottish independence movement of 2014 – have transformed the political landscape, preparing the ground for rejection of a party leadership which continued to refuse to fight waves of Tory austerity.

We can now identify the structural contradictions of New Labour, which spectacularly exploded in the summer of 2015. Blairism at its most powerful represented the perfect triumph of neoliberalism as TINA. But its dominance led to two counter pressures; democratization of the party for the purposes of legitimation and securing volunteer resources, and anti–austerity movements outside the party. At the same time, the lack of its own active mass base left it vulnerable to oppositional forces, whose emergence was facilitated by the two above–mentioned counter–tendencies. Furthermore, the depth of New Labour’s dominance – in terms of the absence of a well–organized alternative – concealed the shallowness of its hegemony, rendering its supporters incapable of warding off threats until it was too late. And the weakness of parties to the left of Labour in England, compared to most Continental European countries and Scotland, is what led to the expression of anti–austerity politics in the Labour Party, in which, out of all labour parties, neoliberalization had proceeded to the furthest depth. Corbyn’s victory was definitely not inevitable; it is not difficult to imagine that one of the New Labour MPs may not have lent their nomination to him, or even just submitted it a few minutes late, which would have precluded his candidacy to begin with. But such “accidental” aspects of the win do not preclude deeper tendencies at work, and they are also important in terms of understanding the political landscape we now encounter with Corbyn as party leader.

The Contemporary Left and Possibilities of a New Party Form

What are the political situations facing the the new Corbyn leadership? No amount of election euphoria can hide the most fundamental fact that Corbyn is in an extremely fragile position in the party. Most obviously and consequently, more than 90 per cent of MPs are New Labourites of one sort or another, reflecting long years of New Labour dominance; no other party leader in history started with such a hostile Parliamentary Labour Party, precisely because MPs used to have significant votes in leadership elections. While Corbyn appointed John McDonnell for shadow chancellor and his shadow cabinet does exclude overt Blairites, the significant presence of New Labour figures in the shadow cabinet is to some extent unavoidable. New Labour remnants can relentlessly attack Corbyn, with the solid support of the bourgeois media – from Daily Mail to the Guardian editors – that they can count on, combined with real or imagined threats of capital flight and disinvestment; such attacks can lose the party support in polls and/or by-elections, which, having caused it in the first place, they could further use against Corbyn. Their claim of Corbyn’s “unelectability” is indeed backed up by their own ability and willingness to undermine his electability through intra–party attacks. Such destabilization will provide an opportunity for New Labour forces to attempt to kill Corbynism, either through an intra–party coup or more subtle forms of cooptation.

The state of the party beyond the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) does not necessarily offer comfort for Corbynism, even if the strength of New Labour approaches nowhere near that in the PLP. After all, it was a party still largely New Labour until a few months ago: the suddenness of Corbyn’s surge meant that the forces backing him have hardly penetrated any part of the party structure, not even the CLPs, once the bastion of the left. Corbyn’s support among the CLPs was, in fact, much weaker than the actual votes he won; while he won 59.5 per cent of the votes, among the CLPs that endorsed a candidate, he only won 39 per cent of them. Among all CLPs, he was only endorsed by 23.5 per cent. (Compare to 1981, when 78.3 per cent of CLPs voted for Tony Benn.) A poll suggests that he won greater support among registered supporters than members, and among the members, greatest among those who joined after the 2015 election. Ironically enough, the structure of Corbyn’s support base bear a striking resemblance to the form which New Labour regarded as its own: masses of party members, otherwise relatively little engaged in the life of the party, voting for a popular figure in an OMOV election.

Of course, the fundamental difference is that more than ten thousand activists volunteered for the Corbyn campaign. But the structure of Corbynism, at least at this moment, is distinct from that of the New Left of the 1970s that was first and foremost based in the CLPs. Indeed, an electoral system traditionally championed by the left – votes at CLP meetings – would most likely have been more disadvantageous to the Corbyn campaign, whose supporters are less involved in the CLPs. The consequent danger is that most of the Corbyn voters, especially (non-member) registered supporters, remain atomized and isolated after the election; plebiscitary democracy must be extended into deliberative and participatory democracy in the party. The tenuous position of Corbyn’s leadership renders the question of organizational strategy crucial. There is no possibility of Corbynism’s survival without the Labour Party becoming a social movement, as Corbyn himself made it clear.

What does a social movement party look like? Most importantly, such a party becomes an agent of successful political articulation. As political sociologists Cedric de Leon, Manali Desai and Cihan Tugal have argued, politically-articulative parties “integrat[e] disparate interests and identities into coherent sociopolitical blocs”; or, as Antonio Gramsci put it, such a party functions as a “constructor, organizer [and] permanent persuader” of the popular will.[4] It means not only that elections and parliaments cease to be the sole focus of party activities and that party activists become involved in other social movements, but that it articulates a comprehensive worldview, based on institutions that become the focal points of social life for masses of members and activists. Despite their tragic failures in the end, the pre-1914 German Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the postwar Italian Communist Party (PCI) became mass parties with social roots, with their daily newspapers, reading clubs and sports clubs, theaters and bars. Even in the British Labour Party, many local CLPs in the 1970s and ‘80s used to serve as the organizing center of various social movements, even if the scale is not comparable to the SPD or PCI; CLPs organized or participated in demonstrations against Thatcher, sent activists to the anti-nuclear camps at Greenham Common, and to the picket lines at the Miners’ Strike. Such mass parties have become decidedly out of fashion in recent decades. As traditional parties have become hollowed-out electoral machines, the most vibrant tendencies in the contemporary left movements, based on the creation of alternative communities and more profound forms of political engagement and identities, tend to eschew the party form. But any party that seeks to transform the existing power relations must build these politically-articulative capacities and become actors in the entire terrain of struggle, within and outside the state, over social relations of force. The prominence and resources of a major party in the whole society does give it an advantage in terms of becoming a pole of political attraction. However, there do also exist serious contradictions. The logic of elections does indeed differ from that of militant mobilizations; while the latter depends on depth of activist commitment and capacity to disrupt, the former depends on large numbers with limited commitment. In particular, opinion polls have certain disciplinary and performative effects that reify the status quo. The polls showing radical positions as unpopular, based on the existing state of “public opinion,” shift the balance of power within the party so as to disadvantage those advocating for strategies to change the existing distribution of political opinion; and as the party accepts the existing distribution rather than seeking to change it, it gets reproduced. It is not easy to escape the Downsian ghost.

The success of Corbynism – transformation of the Labour Party into a left social movement party with articulative aims and capacities – faces additional difficulties, since it involves transforming an existing large party with powerful forces opposed to it. Such a political project requires both internal and external struggles, which are interconnected. They need local parties as politicized social hubs in the communities that engage in a multitude of extraparliamentary struggles, while cultivating comprehensive and deep political identity among the activists. Without active social mobilizations that can shift the political culture of the country more broadly, internal struggles for Corbynism have little chance of success. The movements can strengthen the Corbyn leadership internally, by weakening the claim that it is electorally disastrous, and less directly but perhaps more significantly, by threatening capital with disruption from below so that the section of bourgeoisie would come to regard attacks on Corbyn as too risky. At the same time, the Labour left cannot neglect what are considered purely internal struggles in the party, even if they seem esoteric or less relevant to broader social movements; mobilizations in general must be converted into concrete forces at the specific loci of power in the party. It is crucial to always pressure New Labour MPs at the CLP level, with a serious threat, possibility and strategy of deselecting Blairite MPs. While such an escalation strategy always bears a risk of defeat the hand of greater offensives from the right, it is unlikely that such offensives would cease in reaction to “peaceful” strategies on the left. Furthermore, the Corbyn’s base must be organized to also capture all other elected office in the party; despite resounding victory for Corbyn, the left has not succeeded in other elections in the party. While the left has majority of the member–elected NEC seats, their candidates lost big in the races for Deputy Leader, London mayoral candidate and members of the Conference Arrangement Committee (Angela Eagle, Diane Abbott, Katy Clark and Jon Lansman, respectively); as they all happened this summer, left candidates could have won if the Corbyn voters had also voted for them.

The dilemma of such a strategy is apparent from the experiences of the Labour left in the 1980s; the tension between seeking to capture and transform the party, and engaging in broader social movements. They sought to broadly mobilize for the left alternative, by securing the party first; but the trench warfare in the internal struggles made it difficult for them to fully become active in extra-party social movements. It was also the source of strategic disagreements among different Labour left groups; the more movement-oriented wing of the Labour left criticized the CLPD, not without justification, for being too absorbed in arcane intra-party affairs at the expense of broader mobilization. But one important lesson for Corbynites from the previous round of Labour left struggles is the importance of creating a mass group or network that organizes the Labour left, which simultaneously fights for transformation of the party and mobilizes against austerity more broadly, without becoming explicitly sectarian. Even though transformation of the party requires them to be active within the party, they must not simply be absorbed by the official party organizations, such as the CLPs. For the Corbyn surge to transform itself into a powerful force over the long term, such a political formation is necessary, to protect the Corbyn leadership from attacks and keep transforming the party to the left without getting co-opted by the party machines; and it can become a kernel of the politically articulative forces. Some intraparty left structure from the 1970s still exists; the CLPD is still active, and is connected with the Grassroots Alliance, which runs a left slate for party committee elections. Jon Lansman, a long–time organizer with the CLPD, coordinated the Corbyn campaign. But much of the Corbyn surge came from outside the existing structure, and there are definite distinctions in political culture between the CLPD and many of the Corbyn activists. CLPD, by the process of self-selection, is composed of those who remained in the Labour Party through the deepest of Blair years, rather than joining other extraparliamentary social movements or the Greens; and they possess institutional knowledge necessary for the struggles of the party. On the other hand, many of the Corbyn campaign activists tend to be influenced by the horizontalist culture of the “Millennial” left. For Corbynism, developing a mutually-supportive relationship between these disparate political cultures is crucial.

Despite the broad popularity of the Bennite left among the party activists, the activists then struggled to create such a mass autonomous organization; and despite its influence gained through skillful organizing, CLPD never had more than 1,200 members nationwide at its peak, and other intra-party formations had difficulties attracting the supporters who would otherwise agreed with its politics, especially outside London. Without minimizing the difficulties of creating such a well-organized group that keeps the activist base constantly engaged without getting absorbed into the party apparatus, there are three factors that create a more favorable condition today, compared to the 1970s and 80s. The most important is the most obvious: the left has already captured the leadership, with the whole institutional and symbolic power associated with it. Despite the leader’s weak standing in the PLP, its office commands more decisive power within the party apparatus, which can protect left activists from “witch-hunts”; but the symbolic dimension is no less crucial. Any attempts to transform parties to the left involve intra-party struggles, which are vulnerable to accusations of divisiveness and damage to the party. But it is the side opposed to the leadership that is particularly vulnerable, because of the common identification of party with its leadership. Robert Michels once called the position of a leader in a party, as “Le Parti, c’est moi”; it is far more difficult for the right to attack the left for divisiveness, when they are the ones opposed to the leader.

The second factor is the leftward shift of the major unions. Historically, union bureaucracies had mostly been the pillar of conservative rule within the party, maintaining close connections with the party establishment; their rightward turn since 1982 was crucial in causing the demise of the Bennite left, and they facilitated the persecution of the left under Kinnock. But New Labour, whose rise they themselves fed, began to alienate the union leaders as they largely refused to reverse the Thatcherite industrial relations framework. Len McCluskey, leader of Unite – the largest union in Britain – in particular became a powerful critic of neoliberal consensus in the party; Unite endorsed and campaigned hard for Corbyn, whose campaign team was even based at the Unite headquarters, and he indeed earned endorsements of unions that represent 70 per cent of all union members in total. Because the party-union link has survived, unions still hold considerable power internally, most importantly in the National Executive Committee (NEC). Of course, the left cannot just count on union machines to always support them; but with a mobilized union base, they are in a more favorable position today. Finally, the presence of social media today gives an advantage to the grassroots. Without resorting to the common trope that exaggerates its roles in contemporary movements, it does solve one specific problem that plagued previous attempts at organizing the grassroots left nationwide – to build robust connections among left activists in different constituencies and coordinate campaigns across them.

However, strategic risks for Corbynism remain significant. Working inside the party still riddled with Blairites renders it difficult to avoid associations with the neoliberal tendencies in the party. For example, Sadiq Khan, the party’s Mayoral candidate in London next year, has claimed that he seeks to be “the most business-friendly mayor of all time.” Corbynites face the dilemma of discrediting themselves by campaigning for such a neoliberal candidate, or refusing to do so and face the charges of disloyalty to the party. The situation is even more contradictory in Scotland, where the left is predominantly pro–independence, there exists a growing left party that emerged out of grassroots radicalism of the independence movement, and the electoral system does not punish smaller parties. The leader of the Scottish Labour Party, Kezia Dugdale, is thoroughly a New Labour figure; she claimed that Corbyn’s leadership would leave the party “carping on sidelines.” In Scotland, the left cannot simply organize around Corbyn in the way it can in England; promotion of any Party interests as such is Anglo-centric and harmful to solidarity with the Scottish radicals.

No one on the left should have an illusion about the Labour Party. The immortal words of Ralph Miliband, at the opening of Parliamentary Socialism (1961), still capture the most fundamental insight into the party; “of all political parties claiming socialism to be their aim, the Labour Party has always been one of the most dogmatic – not about socialism, but about the parliamentary system.” Except that it does not claim socialism to be its aim anymore, and it is exceedingly unlikely that Corbyn can transform it into one, however much he wishes. If the Corbynite forces cannot break such parliamentary dogmatism, it will be unable to seriously threaten the capitalist class interest, and to break the tyranny of TINA, in the world in which even social democracy has been banished for the most part. •

This article was first published by Viewpoint Magazine.