Since the Conservative government of Stephen Harper came to power in 2006, shifts in Canadian foreign policy have been a flashpoint of debate in Parliament, the media, and civil society. There is general agreement that a “revolution in Canadian foreign policy” has occurred, to quote Canadian academic Alexander Moens.

For liberals, Harper’s changes are simply a product of his right-wing ideology and domestic maneuvers, and thus are amenable to executive reform. For social democrats and left-nationalists, the same perspective holds, with the added concern of U.S. influence over Canadian state practices. As Marxists have pointed out, the limitation of these perspectives is the absence of any political-economic analysis of Canadian state power – of any theorization of Canadian foreign policy as an expression of economic, political, and social power dynamics at home and abroad.

For liberals, Harper’s changes are simply a product of his right-wing ideology and domestic maneuvers, and thus are amenable to executive reform. For social democrats and left-nationalists, the same perspective holds, with the added concern of U.S. influence over Canadian state practices. As Marxists have pointed out, the limitation of these perspectives is the absence of any political-economic analysis of Canadian state power – of any theorization of Canadian foreign policy as an expression of economic, political, and social power dynamics at home and abroad.

In this article I provide such a theory of Canadian foreign policy under the Harper government. I examine, in particular, the global context in which Canadian foreign policy operates; the policies of Liberal governments before Harper; the strategy of armoured neoliberalism that Harper has advanced; and the implementation of this strategy in several case studies. I argue that the new Canadian foreign policy is a reflection of the internationalization of Canadian capital and the restructuring of the state as an institution of class domination locally and globally.

The Global Context

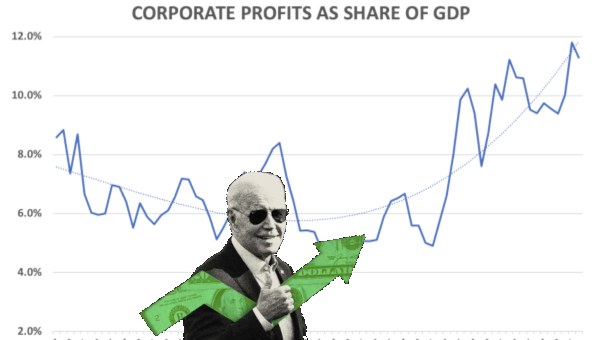

The ‘revolution in Canadian foreign policy’ has to be viewed in relation to global dynamics in the world economy and state system. After the economic crises of the 1970s and 1980s, corporate elites and state managers pursued a ‘neoliberal’ model of capitalism in which wages are reduced, unions curtailed, social programs retrenched, public assets

privatized, and finance and production globalized. The goal was to raise corporate profits by exploiting workers more harshly, and by creating new commodities out of nature and the public sector. Predictably, the neoliberal period has witnessed new patterns of social inequality, uneven development, and political conflict within and between countries.

The world economy, for example, has been characterized by structural imbalances – in particular, by the trade and investment relations within and between the regional blocs of North America, Western Europe, and developed Asia. Anchored by the United States, the North American bloc has been integrated as a preferential trading zone, and has tended to run systematic deficits with the European Union and key Asian economies. American deficits have been covered by dollar inflows to Wall Street and the U.S. Treasury, allowing the U.S. to finance its trade and government deficits, credit bubbles, and military campaigns.

Through these global value flows, U.S. strategy has been buttressed. Since the end of the Cold War, successive U.S. administrations have articulated a strategy of global preeminence. To this end, the U.S. has worked to block the emergence of any competitor in Eurasia, to expand the Cold War security alliances, and to further globalize neoliberal policies.

To support this agenda, the U.S. has engaged in global forms of disciplinary militarism. After 9/11, it increased defence spending to nearly half of world totals, and intervened militarily in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Pakistan, Yemen, Haiti, and Ukraine, among other countries. Despite the failures in Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. has developed new techniques of interventionism, including drone strikes, Special Forces operations, and cyber warfare capabilities. The U.S. has also contrived new pretexts for regime change in ‘rogue’ or ‘failed’ states – for example, through selective applications of ‘democracy promotion’ and the ‘responsibility to protect’ civilians from oppressive governments.

Since the first Gulf War, the Middle East has been the key front of U.S. imperialism. According to U.S. Central Command, the U.S. government’s fundamental interest is in protecting “uninterrupted, secure U.S./Allied access to Gulf oil.” To this end, the U.S. has maintained its key alliances with Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Israel; supported Israeli attacks on several states and resistance movements in the region, and impeded any efforts to end the occupation of Palestine; sanctioned and threatened Iran; and tried to steer the ‘Arab Spring’ in amenable directions – for example, by seeking regime change in Libya and Syria, backing repression in Bahrain and Yemen, and recognizing the 2013 military coup in Egypt. Alongside the war in Iraq, these policies have generated a vicious circle of militarism, underdevelopment, terrorism, and state failure in the region.

Beyond the Middle East, the neoliberal agenda of U.S. grand strategy has also limited development. In 2010, the UN Development Programme admitted that the world economy had experienced “no convergence in income… because on average rich countries have grown faster than poor ones over the past 40 years. The divide between developed and developing countries persists: a small subset of countries has remained at the top of the world income distribution, and only a handful of countries that have started out poor have joined that high-income group.” Furthermore, “within countries, rising income inequality is the norm.”

The logic of global capitalism under U.S. hegemony has thus been one of entrenched inequality and uneven development. With this in mind, how has the Canadian state positioned itself in the global system of empire?

Before Harper: Neoliberalism and Canadian Foreign Policy

Harper’s foreign policy agenda is best viewed as a radical extension of Canadian state practices in the neoliberal period. On both economic and political fronts, four dynamics have

transformed the political economy of Canadian foreign policy.

First, from the mid-1980s to the present, the Canadian state has pursued a project of continental neoliberalism. Under the direction of corporate policy groups and think tanks, the goal of this strategy has been to integrate the U.S. and Canadian economies in free-market ways, and to decompose the Canadian labour movement through new forms of regional competition. The free-trade agenda, which was embodied in the 1988 Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement and the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement, was a vital strategy for capital, and helped to raise the rate of profit for Canadian business from 1992 to 2007.

Second, the Canadian state worked to globalize production and investment on a broader scale. In fact, the regional strategy of continental neoliberalism was designed as a stepping-stone for Canadian corporate expansion in the world economy, particularly through foreign direct investments. By 1996, Canada had become a net exporter of direct investment capital, and Canadian corporations became leaders in several global sectors, including energy, mining, finance, aerospace, and information-and-computer-technologies. Directorship interlocks between the top tier firms of Corporate Canada and the top firms globally also increased, with Canadian corporate elites expanding their position in the ‘North Atlantic ruling class.’ On the trade front, Canada began to register a pattern in the balance-of-payments, running deficits with Europe, Asia and less developed economies, and overcoming these deficits with surpluses with the USA. In these ways, the NAFTA zone supported the global links of Canadian capital.

Third, in support of these dynamics, Liberal governments worked to erect a global architecture for transnational neoliberalism. In the 1990s, this was achieved through the World Trade Organization, APEC forums, and efforts to establish a Multilateral Agreement on Investment through the OECD. In the early 2000s, the Chrétien government also sought a Free Trade Agreement of the Americas. Building on the mass campaigns against CAFTA and NAFTA, Canadian activists played a critical role in protesting these trade and investment initiatives, most notably during the 2001 Summit of the Americas in Québec City.

Fourth, Liberal governments also began a rethink of Canadian foreign policy in light of the globalization agenda and Washington’s primacy strategy. Most notably, in 1999, the Chrétien government supported NATO’s illegal attack on Serbia, and in 2001 sent troops to Afghanistan. The Chrétien and Martin governments also increased budget lines for the Department of National Defence (DND) and for Canada’s national security and intelligence agencies.

To support these efforts, they also issued several strategy documents, including the National Security Policy (2004) and the International Policy Statement (2005), both of which called for new security measures domestically and new military capabilities internationally. In addition, both governments further aligned Canada’s security and immigration policies with the U.S., as demonstrated in the Smart Border Declaration (2001), the Safe Third Country Agreement (2002), and the Security and Prosperity Partnership (2005). Although Canada refused to participate formally in the 2003 Iraq war, the Chrétien government offered multiple forms of military assistance, including surveillance aircraft, naval ships, military personnel on exchange programs, and a military deployment to Afghanistan to relieve U.S. soldiers for the Gulf. The Martin government also deployed troops to Haiti in support of the 2004 coup d’état, and its Emerging Market Strategy (2005) delineated an array of supports to Canadian corporate expansion in the Third World.

The Harper government thus inherited a nascent apparatus for the internationalization of Canadian capital and the militarization of Canadian foreign policy in conjuncture with U.S. imperialism.

Armoured Neoliberalism: Harper’s Grand Strategy

The novelty of Canadian foreign policy under Stephen Harper’s government has been the upfront class-consciousness of its geopolitical and geo-economic agenda. With support of the corporate community and defence lobby, the Harper government has articulated a new grand strategy of armoured neoliberalism: a fusion of militarism and class warfare in Canadian state policies and practices. The aims have been three-fold: to globalize Corporate Canada’s reach; to secure a core position for the Canadian state in the geopolitical hierarchy; and to discipline any opposition forces – both state and non-state – in the world order.

In pursuit of these goals, Harper has operated as “the ideal personification of the total national capital,” to quote Friedrich Engels. With this in mind, his government has developed new state capacities for military propaganda; propped up right-wing constituencies domestically for external purposes; and fortified a national security apparatus to monitor and suppress any challengers to the state/corporate nexus in Canada.

At the level of doctrine, this agenda has been spelled out in several statements. In 2008, the Canada First Defence Strategy highlighted “terrorism,” “failed and failing states,” and “insurgencies” as key security threats, and argued that Canada’s highly globalized economy relied on “security abroad.” It promised $490-billion in new military spending, and envisioned a “combat-capable” military that is interoperable with U.S. forces.

In 2013, the Harper government released its Global Markets Action Plan, according to which “all Government of Canada assets [will be] harnessed to support the pursuit of commercial success by Canadian companies and investors in key foreign markets.” As part of this,

it articulated an “extractive sector strategy” for Canadian resource investors abroad.

To support such economic interests, the Harper government published Building Resilience Against Terrorism (2012), also known as the Counter-Terrorism Strategy (CTS). This document has been the key legitimation strategy for Harper’s national security and foreign policy agenda. It begins by identifying “Islamist extremism” as the leading threat to “Canadian interests.” The importance of this threat assessment is that it bases Canadian strategy on an apolitical and ahistorical understanding of Islamist violence, one that ignores the history of Western foreign policy in the Muslim world and conflates different types of Islamist movements. In the process, it constructs a one-dimensional menace against which Canadian forces must be mobilized on a permanent basis.

Second, the CTS targets domestic movements of “environmentalism and anti-capitalism” as potential sources of terrorist violence against “energy, transportation and oil and gas assets.” It thus seeks to legitimate a class-based project of securitization in the Canadian state itself, one that can surveil and discipline any working-class or environmental challenges to Canadian capital.

The key strategy of the Harper government, then, has been to openly define the foreign and domestic interests of Canadian capital as the raison d’étre of the state. The aim is to consolidate a national security state that can advance the global interests of Canadian capital, and suppress any opposition to this agenda. With this in mind, the Harper government has further restructured the national security and foreign policy apparatuses.

For example, under the Harper government, funding for Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC), a federal agency for global signals-intelligence, increased dramatically to $422 million in 2013. With such new resources, CSEC has been involved – as part of the ‘Five Eyes’ group of countries – in metadata surveillance at home and abroad; in foreign industrial espionage in support of Canadian mining and energy corporations; and in covert spying operations for the U.S. National Security Agency.

By 2010/11, funding for the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) also increased to $506-million, giving CSIS new capacities for foreign and domestic intelligence work. CSIS has been involved in communications monitoring in Canada, and in surveillance operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. It has also been complicit in the detention and torture of Canadian citizens abroad, as demonstrated in the cases of Maher Arar, Abousfian Abdelrazick, and Omar Khadr, among others. In support of this, the Harper government closed the Office of the Inspector General of CSIS, and now allows CSIS to use intelligence gained through torture by foreign security services. Within Canada, CSIS has collected intelligence on the global justice and peace movements, and has targeted indigenous activists, mosques, and migrant organizations.

The Harper government has revolutionized the foreign policy apparatus in other ways. In March 2013, the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) was folded into a new Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD). In the process, Canada’s development assistance work was further linked to the economic and geopolitical interests of the state. In particular, it was torqued for making developing economies “trade and investment ready,” as former-Minister Julian Fantino put it. Alongside Export Development Canada and Natural Resources Canada, the DFATD has anchored a ‘whole-of-government’ effort for Canadian mining investment in the Third World.

Although the ‘commercialization’ of Foreign Affairs began in the early 1980s, the Harper government has advanced this process in novel ways. In particular, it tasked DFAIT with reviewing ties with emerging economies in Asia, coordinating more closely with the U.S. State Department on trade and global security, and developing a ‘Strategy for the Americas’ in light of Canadian corporate expansion in the region (see below). It also has negotiated a series of bilateral foreign investment agreements, and supported a new arms exporting strategy in liaison with the Canadian Commercial Corporation and defence industry groups.

In 2012, it also inked a Foreign Investment Protection Agreement with China, with the two-fold aim of (1) securing and protecting long-term Chinese investment in Canada’s growing industrial sectors; and (2) offsetting the decline in U.S. demand for Canadian exports with new patterns of trade and investment with China and Asia. While the Agreement does not provide the same reciprocity to Canadian investors in China, and while it limits Canadian democracy with respect to economic, environmental, and First Nations policies, it fully accords with the neoliberal project of globalizing Canadian capitalism. With this in mind, Harper’s DFATD has also worked on dozens of other investment and trade agreements with developing countries, many of which are recipients of large-scale investments by Canadian banking, mining, and energy firms.

The Harper government has also restructured the Department of National Defence. In October 2012, the Canadian Forces were given two command structures: the Canadian Joint Operations Command and the Canadian Special Operations Command. By 2011, Harper had increased defence spending to $22-billion, the highest level since the Second World War. In this context, the Conservative government increased regular and reserve personnel, and launched a major procurement effort, though the latter has been limited by austerity measures, the withdrawal from Afghanistan, and political incompetence. Harper also has withdrawn Canadian forces from any significant UN peacekeeping operations, supported DND efforts to build seven overseas operational support hubs, and endorsed the new DND focus on counterterrorism, defence diplomacy, and interoperability with U.S. and NATO forces.

To support these efforts, it has tried to inculcate a new culture of militarism in Canadian civil society – for example, through yellow ribbon campaigns, war commemorations, recruitment drives, fallen soldier ceremonies, and military spectacles at professional sporting events. As historians Ian McKay and Jamie Swift argue, this “state-orchestrated cultural revolution” has aimed to “realize a specific vision of Canada, one of money for arms, more respect for soldiers, and more muscularity in foreign affairs.”

In these ways, then, the Harper government has embedded a new calculus of power in the grand strategy and institutional resume of the state. It has consolidated a national security apparatus at home, and redefined the strategy of Canadian foreign policy abroad, around a class-based imperialism.

Exploitation and Destruction: Harper In Action

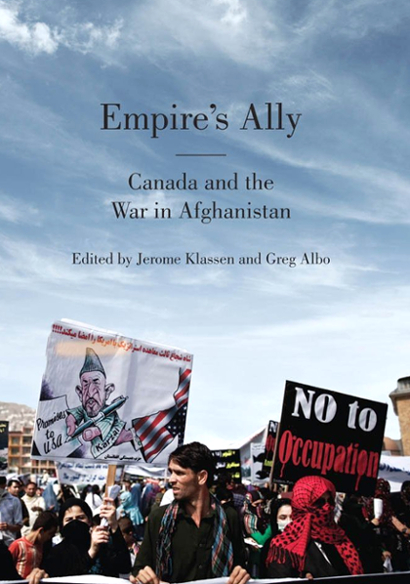

The key foreign policy actions of the Harper government have revealed the logic of armoured neoliberalism in Canadian grand strategy. The war in Afghanistan has been the most important case in point. Upon taking office, the Conservative government fully embraced the counterinsurgency mission in Kandahar, and continued to extend the deployment until Spring 2011, after which Canadian forces were mandated with a three-year training mission for Afghan security services. Through a Strategic Advisory Team in President Karzai’s office, Canadian military personnel were entrenched in the Afghan state, and played a key role in drafting a neoliberal development plan for that country. This plan involved privatizing state assets, deregulating the domestic economy, and liberalizing trade and investment. International donors largely managed the distribution of aid funds, and NGOs established projects across the country, without coordinating with the state.

Under the Harper government, the majority of Canadian aid spending was militarized as part of supporting the war in Kandahar. However, as Nipa Banerjee, the former head of CIDA operations in Afghanistan, has revealed, “all the projects have failed” and “none of them have been successful.”

Under the Harper government, the majority of Canadian aid spending was militarized as part of supporting the war in Kandahar. However, as Nipa Banerjee, the former head of CIDA operations in Afghanistan, has revealed, “all the projects have failed” and “none of them have been successful.”

The Canadian military mission also failed to achieve its stated aims of pacification, democratization, and development. While it prevented the Taliban from taking over Kandahar City, it failed to defeat the insurgency, antagonized the population, empowered warlords and drug traffickers, killed civilians and destroyed infrastructure, and knowingly transferred detainees to torture by Afghan security personnel. In these ways, Canada practiced a neoliberal form of militarism in Afghanistan – one that liberalized the Afghan economy, and established a client state for western influence in the region.

The same logic was apparent in Harper’s Strategy for the Americas, which was designed to support Canadian corporate investment, bolster conservative governments, curry influence in Washington, and beat back left-wing movements. Nowhere was this more evident than in Honduras, where, in June 2009, the democratically elected President was abducted and flown out of the country by the military. He was replaced by a dictatorship, led by prominent members of the Honduran oligarchy, which cracked down violently on demonstrations.

Canada quickly emerged as one of the dictatorship’s closest allies, consistently blaming the former-President for the crisis and lauding the accomplishments of the dictatorship. Though the OAS immediately ejected Honduras, demanding the restitution of democracy, Canada lobbied to have Honduras re-instated. Indeed, Canada helped the dictatorship create

the appearance of democracy and rule of law, twice accepting the results of fraudulent elections and sending a representative to a sham ‘Truth and Reconciliation Commission’, despite Amnesty International’s denunciation of the dictatorship for using death squads to assassinate activists and journalists.

In 2011, Canada announced that it had signed a free trade agreement with Honduras, which would further reduce taxes and operating constraints on mining, garment, and tourist industry capital in Honduras. Canada has also helped train Honduran police, as part of Canada’s emphasis on security – which makes sense in a context where Honduran communities have been mobilizing against Canadian companies like Goldcorp and Gildan.

Similar interests guided the Conservative government’s interventions in Haiti after the 2012 earthquake. In public statements, Foreign Affairs Minister Lawrence Cannon averred that Canada’s military deployment was “all about solidarity… all about helping [Haiti] in its hour of need.” Classified DFAIT documents reveal, however, that Canada’s main priority was containing both “the risks of a popular uprising” and the “rumour that [left-wing] ex-President Jean-Bertrand Aristide… wants to organize a return to power.” The same documents reveal that Canada also supported a neoliberal reconstruction effort, one that involved a “real paradigm shift” and a “fundamental, structural rebuilding of [Haitian] society and its systems.” With this in mind, roughly 97 per cent of Canadian relief funds bypassed the Haitian government, going instead to the UN and international NGOs. As a result, it compounded what Canadian academic Justin Podur calls the “new dictatorship” in Haiti: a coalition of foreign and domestic elites that dominate and exploit the country through neoliberal methods of political, economic, and military control.

The same practices have appeared in Harper’s Middle East policies. To begin, Harper has given unqualified support to Israel and its apartheid system in Palestine. As part of this, he changed Canada’s voting patterns on Palestine at the UN, and boycotted the elected Palestinian Authority in 2006. Harper also backed the Israeli assault on Lebanon (2006), as well as successive Israeli attacks on Gaza, which the UN and human rights groups have described as war crimes. To build support for these policies, the Harper government has established strong ties with the Israel lobby in Canada, and has disingenuously conflated the Boycott, Sanctions and Divestment (BDS) movement with Anti-Semitism.

The Harper government was also quick to join NATO’s 2011 war for regime change in Libya. While popular protests against Gadhafi’s government had emerged in parts of the country, and while the UN Security Council had sanctioned a no-fly zone, the NATO mission focused primarily on bombing government, military, and civilian infrastructure in support of the insurgency. Canadian intelligence officers had warned the DND that, “there is the increasing possibility that the situation in Libya will be transformed into a long-term tribal/civil war.” They also warned that, given the presence of “several Islamist insurgent groups” in the opposition, the Canadian-commanded NATO mission ran the risk of becoming “al-Qaida’s air force.” That Canada, the U.S., and NATO ignored such warnings indicates (1) the persistent fallacy of such ‘humanitarian wars’; (2) the western strategy to contain the Arab Spring and to exert greater control over Libya’s oil wealth; (3) the strategic interest in testing U.S. AFRICOM’s reach into the continent; and (4) the ongoing use of jihadist groups for imperial ends.

In the wake of Libya, Canada also established closer ties to the economies and security apparatuses of the Gulf Arab monarchies. For example, Canadian arms exports to the region have boomed under the Harper government, reaching tens of billions of dollars. Saudi Arabia, in particular, has become a close ally of Canada’s Middle East policy. It has purchased approximately $15-billion in Canadian military exports; supported other business ventures by Canadian firms such as Bombardier and SNC Lavalin; and participated in Canadian navy and air force exercises. As Canadian journalist, Yves Engler, has noted, “the Conservatives’ ties to the Saudi monarchy demonstrate the absurdity … of Harper’s claim that ‘we are taking strong, principled positions in our dealings with other nations, whether popular or not’.”

Finally, Harper was quick to insert the Canadian military into the U.S. war against Islamic State (IS) – in particular, through a Special Forces training mission for Kurdish peshmerga militias, an air campaign of CF-18 Hornets, and an aid program for Iraqi and Syrian refugees in the region (though not for settlement in Canada). While Canadian efforts have achieved some success in containing IS capacities in northern Iraq, they fit within a larger strategy that is highly contradictory.

First, the war strategy ignores how the sectarian, neoliberal policies of the U.S. occupation of Iraq created the impetus for IS’ emergence. Second, it ignores how the western strategy of regime change in Syria created another opportunity for IS to advance alongside other jihadist currents, including al-Qaeda in Syria. Third, it involves military forces from the Gulf dictatorships, which share and promote the same ideology as IS. Fourth, it ignores the sectarian character of the Iraqi government and its role in alienating the Sunni population. Fifth, judging from the military engagements to date, it is unclear if western strategy is to defeat or simply contain IS for imperial ends in the region. Sixth, the strategy has not confronted the active role of NATO-member Turkey in supporting IS. And finally, it has refused open collaboration with other forces in the region – namely, Iran, Hezbollah, and the Syrian government – that are also fighting IS and al-Qaida.

For these reasons, Canada’s new engagement in Iraq and Syria is an imperialist war that will likely compound the cycle of militarism, sectarianism, underdevelopment, and state failure in the region, to the detriment of popular struggles.

The conflict in Ukraine has been the last major front of Harper’s imperial statecraft. The conflict has been over-determined by several dynamics of geopolitical and geo-economic rivalry in the post-Cold War period, including the eastward expansion of NATO, U.S. violations of Russian sovereignty, NATO’s rejection of any Russian security interests near its borders, U.S. plans for nuclear superiority, western fury over Russian assistance to Syria, and fears of Russian-Chinese ‘balancing’ of U.S./NATO dominance. The ‘New Cold War’ of western foreign policy partly explains the authoritarian nationalism of Putin’s government and its actions in Crimea and eastern Ukraine after the U.S.-backed coup d’état in Kyiv in February 2014.

In this conflict, Canada has played a prominent role. In the events leading up to the coup, opposition protestors were allowed to occupy the Canadian embassy in Kyiv for several days. Canada also recognized the coup government and the subsequent elections of limited legitimacy. In addition, it provided hundreds of millions of dollars in bilateral aid; backed a host of NATO Reassurance Measures; imposed a sanctions policy (albeit with loopholes for Canadian corporate ties with Russia); and deployed military trainers for the counterinsurgency in eastern Ukraine. In June 2015, it also signed a free-trade agreement with the Ukrainian government, which has subsequently solicited Canadian investors to purchase billions of dollars of soon-to-be privatized public enterprises. In taking these positions, the Harper government also aimed to buttress its links to conservative forces in Ukrainian-Canadian communities in several urban ridings.

However, Harper’s policies vis-à-vis Russia and Ukraine are not driven by such electoral machinations. While corporate interests are largely peripheral to this conflict, the Harper government has worked to advance the class interests of Canadian imperialism. As ‘the ideal personification of the total national capital,’ Harper has escalated the political, economic, and military conflict with Russia as a means of asserting Canadian state power in a changing global order, one that is increasingly multi-polar and resistant to U.S./NATO preeminence. As a result, the ‘whole-of-government’ engagement with Ukraine fits within a larger system of economic, political, and military rivalry at the global level. It thus exemplifies the class-based nature of Harper’s foreign policy, and his strategic mobilization of domestic constituencies for political, economic, and military purposes abroad.

Conclusion

Harper’s foreign policy is an avatar for changing dynamics of economic and political power in Canada and around the world. Although Harper himself has played a critical role in conceptualizing and advancing the new grand strategy of armoured neoliberalism, his government is merely supporting the logic of Canadian corporate expansion. As such, Harper’s imprint on Canadian foreign policy is best understood as a hegemonic strategy of the state-capital nexus in the context of neoliberal globalization and U.S. primacy objectives.

With this in mind, any strategy to challenge the new Canadian imperialism will have to address the political economy of capital and class at home and abroad. To this end, the further building of working-class, indigenous, and environmental movements will be of vital service to peace and global justice. •

Jerome Klassen thanks Tyler Shipley, Anthony Fenton, and Greg Shupak for support in writing this article.

This article was first published in the September/October 2015 issue of Canadian Dimension.