“Of political parties claiming socialism to be their aim, the Labour Party has always been one of the most dogmatic – not about socialism, but about the parliamentary system.” That’s how Ralph Miliband opened his classic 1961 text Parliamentary Socialism, a critical analysis of the party that most of the British left wanted to capture.

Miliband was skeptical of that plan, as was his later collaborator Leo Panitch. But during the great upsurges of the early 1980s – which saw the growth of a radical Labour left represented by Tony Benn and others, as well as the miners’ strike of 1984–85 – both thinkers resisted the “new revisionism” of intellectuals like Eric Hobsbawm and Stuart Hall who viewed the “Bennites” and Trotskyist entryists rather than a staid leadership as the source of Labour’s problems.

However, that supposed realism would win the day, eventually ushering in New Labour and the further rightward drift of the party – the backdrop for Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour leadership campaign.

With the results of the leadership election set to come in September 12, Jacobin‘s Bhaskar Sunkara spoke with Panitch, a York University professor and Socialist Register co-editor. They discussed the legacy of Tony Benn, how Ed Miliband’s reforms to the Labour Party inadvertently laid the ground for Corbyn’s insurgency, and whether Labour could be transformed into something it never was – socialist. This interview was first published by Jacobin magazine.

Bhaskar Sunkara (BS): Jeremy Corbyn’s success has reminded people of Tony Benn and his struggle to win control of the Labour Party a few decades ago. Politically, where does he stand in relation to Benn, who had a structural critique of capitalism and wanted to transform the Labour Party into a real agent for socialism? Is he in the same tradition?

Leo Panitch (LP): Well, I certainly wish that Tony Benn were around to see this. Certainly, in talking to him in his last years, he wasn’t expecting something like this to happen, and he was a bit depressed about the prospects for the Labour left. But it does go to show you that the kind of democratic socialist struggle that we are embarked on is a marathon, not a sprint.

Jeremy Corbyn exactly fits in the Bennite tradition and indeed was part of the attempt – of which Tony Benn was the prominent voice – to change the Labour Party into a vehicle for mobilization for socialist change in Britain. This effort goes back to the effects of the 1960s New Left, the anti-Vietnam activism, the beginning of the women’s movement, the general thrust for participatory democracy.

Jeremy Corbyn exactly fits in the Bennite tradition and indeed was part of the attempt – of which Tony Benn was the prominent voice – to change the Labour Party into a vehicle for mobilization for socialist change in Britain. This effort goes back to the effects of the 1960s New Left, the anti-Vietnam activism, the beginning of the women’s movement, the general thrust for participatory democracy.

There was an upsurge in the Labour Party in the early 1970s and through the early 1980s, until it was defeated by an alliance of the Labour right – which eventually turned itself into New Labour under Tony Blair – and the “old left” in the Labour Party, the Michael Foot wing of the party, represented by parliamentarians and left-wing policy types and linked to the trade union bosses.

What Benn represented instead was a strong force inside the party saying that if you couldn’t change and democratize the Labour Party, you couldn’t change and democratize the British state. That was the central theme of the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy. It’s very significant that the brilliant young organizer of that campaign, Jon Lansman, is now a central figure in the Corbyn camp.

All these developments were reflected in the attempt to break the control of parliamentarians and career politicians over the Labour Party, an attempt to allow for constituency parties to reselect their MPs, an attempt to make sure that party congress resolutions would be taken seriously by the party leadership.

And this was also an attempt to allow for a mobilization at a local level. This was especially important for Corbyn who was part of the municipal radicalization in the 1970s which culminated with their great successes at the Greater London Council, under Ken Livingston.

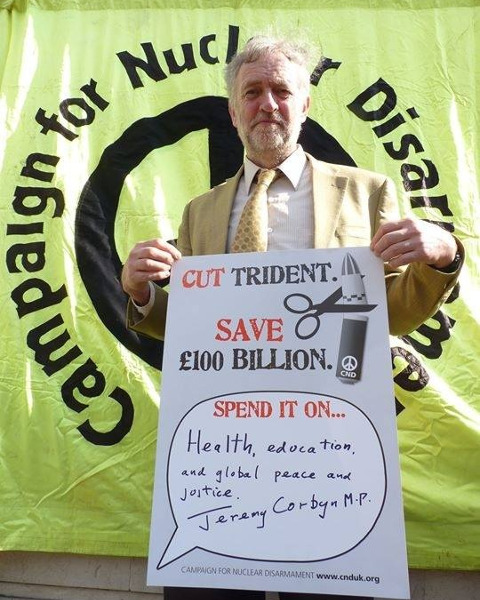

Corbyn represents all of this. He also harkens back all the way to the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament at the height of the Cold War, he’s the vice chair of the remnants of that organization and opposes the renewal of the Trident submarine, the British “nuclear deterrent.”

In all these respects, Corbyn is very much carrying forward what was isolated, marginalized, and eventually defeated in the Labour Party – and in other social-democratic parties in Europe. And out of all those parties, this left insurgency only seems to have reappeared in the Labour Party and only in the last few months.

BS: Let’s talk about those pushes from within social-democratic parties in the 1970s, this process was also seen in places like Germany and Sweden . . .

LP: Well, in Germany in the 1970s many Young Socialists in the SPD were expelled, while in the case of Sweden the attempt was made through the labour movement, giving rise to the wage-earner fund proposal, the Meidner Plan. You can find traces of this radical democratization thrust through the decade in every social-democratic party in the 1970s, but in every case it was defeated.

It was very difficult, even impossible, to transform these parties. Given that social democracy accommodated itself so long ago to a compromise with conventional parliamentarism as defining a “democratic capitalism” they were content to manage, the leadership of those parties had every right to claim that the party was “theirs” and what their tradition represented.

The attempt to change the Labour Party always harkened back to the idea that “we were going to make the party socialist again.” And the Right were always somewhat correct in saying that the Labour Party was never really socialist, at least in the way the reformers meant.

BS: We’re seeing this left-wing energy return within the Labour Party, and not outside it. How much of this is due to the particularities of the English political system, with first-past-the-post voting and so on? Or are there deeper roots?

LP: I think that’s partially it, but I think it also has to do with the extremity of Blairism, the way in which Blair and New Labour embraced Thatcherism.

Thatcher said, with good reason, that her greatest success was Tony Blair. It has to do with the way the Murdoch press in Britain, including that portion of the press that workers read, papers like the Sun, which used to be the Labour Party newspaper, the Herald . . .

BS: Until the 1950s, right?

LP: Yes, that became the Sun and Blair did a deal with Murdoch to make sure the press was behind him.

As an aside, it’s worth remembering that the Guardian played a tremendous role in defeating the Bennites, often featuring Eric Hobsbawm arguing that given the threat of Thatcher, a “popular front” position had to be turned to and there needed to be a unity of forces of everyone to the left of Thatcher. That’s one of the things that influenced young people like the Milibands and where they went politically. But it went so far under Blair and New Labour that the party actually embraced the financialization of capital under the City of London.

New Labour explicitly tried to distance themselves from the unions in a way that denied in any sense the class basis of the party. They couldn’t completely abandon the labour unions, because so much of the party’s resources and votes came from there, but they came as close as they could.

And, of course, there was also the Iraq War. One of the reasons why Ed Miliband won the last leadership election, over his brother David, was a combination of people within the party disgusted by that venture and the union bloc vote. He picked up on this discontent with the party, even though in a sense he was still triangulating between this content and the fact that whole parliamentary elite of the party was still Blairite.

But in the wake of Ed Miliband, the remarkable development is that things have swung not all the way back to the New Labourites, but rather to the left.

BS: Certainly helped by transformations in the leadership election process itself . . .

LP: Yes, this mode of undertaking elections is new, introduced by Ed Miliband just a couple years ago.

One of the victories of the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy after a decade of struggle was that instead of the leader always being selected just by members of parliament – something that showed just how parliamentarist the party was – an electoral college was constructed. It consisted of one-third MPs, one-third constituency party members, and one-third trade unions.

From those reforms a few decades ago until this election, that’s how it operated.

BS: Miliband got rid of the “bloc vote,” in favor of a “one member, one vote” system, right?

LP: Ed Miliband was elected largely due to his winning the third of the vote granted to the unions. And he was always under pressure from the Labour right who said that he was too beholden to those unions (though he, of course, was not). When there was tremendous pressure from this right over a kerfuffle over a candidate selection process in Falkirk, he responded by saying that they were going to break with the way that unions affiliated with the Labour Party. He said that he would rather have 300,000 active trade unionists in the party than 3 million paper trade unionists affiliated to the party. Because he was “moving away” from the trade union bosses, he was able to win over the parliamentarians, to convince them to drop their privileges, as well, and have a one-person, one-vote system.

Of course, the Labour right think that people like you and I, or even Corbyn, are a tiny minority of Neanderthals. They thought that if you had an American primary style election, it would ensure that they would always win. They were dead wrong.

In May, when the election was held, there were only 200,000 Labour Party members – down from a million in the heyday of the party. But in the past few months, 178,000 trade unionists have joined as individual members. Another almost 200,000 have paid 3 pounds to sign up as Labour Party supporters to vote. Even more significantly, 80,000 new members joined after the election, some of them the day after the election.

BS: What happened to the Michael Foot-types? Did they oppose Miliband’s reforms?

LP: So overwhelming was the Blairite sweep of the party, those currents weren’t really a factor anymore. People, of course, always thought Gordon Brown was closer to that tradition, but that wasn’t really true.

BS: That was more his rhetoric and affect, he was less of an outsider to the labour movement than Blair but had virtually the same politics.

LP: I think I can now quote Ed Miliband well over a decade ago, before he was an MP and when he was still working in Brown’s Treasury office, telling me privately that you couldn’t put a piece of litmus paper between Blair and Brown.

BS: But basically we’re saying that this reform by Miliband that might have seemed like a move to the right at the time in fact laid the groundwork for a lot of the activists and young people streaming into the party. What does it mean for the class nature of the party going forward, with labour having less of an institutional role?

LP: I think it does. We have to be careful talking about the changing class nature of the Labour Party given the extent to which the composition of the working class itself has changed. So it isn’t the old class basis of the Labour Party, with the exception of a few areas, it’s a much more diverse group of workers coming into the Labour Party. More significantly, when Miliband said that I’d rather have 300,000 active trade unionists than 3 million paper members, I remember saying to him that he’s absolutely right, but to make them active would require fundamentally changing the Constituency Labour Parties (CLPs) into centers of working-class life at the local level.

The challenge for Corbyn is to take advantage of how his campaign has enlivened the CLPs and turn them into continuing centers of political activity and really enliven them in terms of longer-term education and mobilization. There have always been socialists in the Labour Party. There have always been socialists in every social-democratic party. But for them to be effective, the very nature of the party at the local level, not only at the national level, needs to change.

That’ll be an enormous challenge. It’s not just a matter of saying that the party congress will have more control over policy or that the constituency parties will play a more important role than the national executive community. Much more important is that they be involved in daily social life and begin to create a vision and an image and a capacity where they live for different modes of production and consumption.

I think that Corbyn would be the first person to admit that most constituency parties at the local level aren’t close to that, though many people around him would like that transformation to happen. But that’s an enormous challenge. It requires someone at the top who is oriented in that direction and tries to turn party and trade union resources to it. But that’s what this is going to require, if the developments are really going to go anywhere other than a mere shift in policy, or even just rhetoric. It’ll certainly just do that much, but if it’s going to go further than that in a socialist direction then it needs to lay this kind of base.

BS: What do think the response of the Labour right would be to a Corbyn victory tomorrow? Would they split and link up with the liberals like the Social Democratic Party (UK) did in the early 1980s? Or are they going to stay and fight?

LP: I must say that I initially thought when I started to get notes from friends saying “do you see how well Corbyn is doing?” that there was no way that he could win, because the center-right parliamentarian wing of the party would leave the party or at least signal that they would break and this would be all over the press. And there has been that kind of noise. But as the writing is on the wall for a Corbyn victory – by virtue of this vast expansion of the Labour Party membership and his support among many of the old party members – these people are looking back at the history of the early 1980s, when key figures in the party created the SDP.

Roy Jenkins, David Owen, Bill Rodgers, Shirley Williams . . . all of them destroyed their political careers and ended up in the House of Lords with very little political influence. The mainstream politicians in Labour likely don’t want to go down that same path. That may be because the Liberal Democrats are in trouble, as well, and any alliance with them would not offer electoral prospects. It may also be because they think Corbyn will burn out and they’re encouraged in this by the Guardian, which once again, is not playing a good role in this battle.

BS: There’s a great headline from a couple months ago which seems to capture the mood among the center-left media: “Jeremy Corbyn to ‘bring back Clause IV’: Contender pledges to bury New Labour with commitment to public ownership of industry.”

LP: Of course, if he were to do so it would be a good thing. He is committed, however, to renationalizing certain key industries, including the railways – and there’s over 70 per cent public support for this in the opinion polls.

These guys think these policies are all old-hat, but it’s becoming ever more relevant in the twenty-first century. The only means of coping with the long-term stagnation of capitalist economies and the crisis of climate change is with some form of democratic economic planning.

The policy foundation of the strategies that Corbyn and a lot of people like him is the Alternative Economic Strategy, the economic program of left-Labour during the 1970s and early 1980s was something that Benn took up and kind of democratized. He added to what was policy proposals, real ideas about education and mobilization . . . this is exactly the tradition that Corbyn comes from.

BS: There’s been fear that if Corbyn wins there would be some sort of recourse from the right-wing of the party, contesting the validity of new member votes.

LP: I don’t think that you’re going to see much of that. Corbyn’s support is too overwhelming. They’ll try to change the way the Shadow Cabinet is selected and do other procedural things to make his life miserable, but the main thing they’ll do is what E. P. Thompson once called “leaking into the public urinal.”

They will cause untold headaches by going to the press, they will constantly be revealing that can’t live with a party inquiry into whether one should do away with the Trident system (also the position of the Scottish National Party). They will do everything they can to make it look like a coalition with the SNP, Plaid Cymru, and the Greens is on the horizon, with proportional representation as its goal and that this will “undermine the unity of the United Kingdom.”

Their hope is that this will bring him down in a couple of years and there will be a turn to the Blairites. I think they’re wrong about the mood of the party. I think these guys have had their day.

BS: Practically, for socialists in Britain, for people who don’t think that the Labour Party is in the long-run a vehicle for socialism but in the short-term certainly support Corbyn, are there any lessons from the past about how socialists could be both good allies to the Labour left but also critical when necessary.

LP: It’s also been my view, as Ralph Miliband put it in the mid-1970s, that the greatest illusion of the British left was the idea that the Labour Party could be turned into a socialist party. Although I was enormously sympathetic to the Greater London Council and the Bennite push for a different sort of Labour Party, I always thought it would be defeated because the Labourite center-right and even center-left always showed their loyalty to the party unity and they would band together against the Left were it showing a capacity to take over the party. That proved largely right.

That said, I’ve also always been of the view that one does need a party outside of the Labour left, outside of social democracy, looking to reground the movement for socialism in a non-Leninist but also non-social-democratic way.

It seemed to me most likely that that would be successful if a portion of social democracy and a portion of the Communist movement and other radicals would break off and join that attempt. That’s to some extent what’s happened with the left parties in Europe now.

If this can happen from the top, however, in the case of the Labour Party, that’s fine too. If the party splits, as I think could happen if the constituency Labour Party is transformed and New Labour either leaves or is kicked out, the realignment might happen from the break of these elements or even the center-left from the Labour Party, rather than from the Left leaving the party. At least that seems to me a possibility now. •