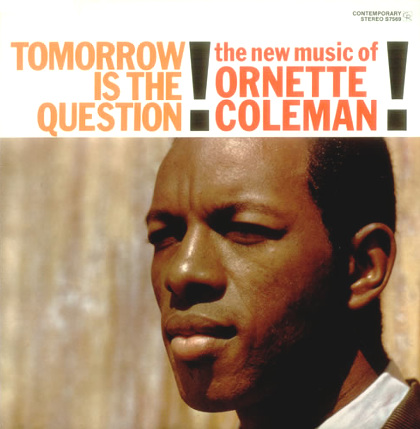

Ornette Coleman died in June of a cardiac arrest on the same day as an infamous bad guy actor, Christopher Lee and legendary professional wrestler Dusty Rhodes. One can’t help but chuckle at the Colemanesque improvisation of the Grim Reaper. Coleman was perhaps the jazz musician with the most theoretical depth, even if his own cultural production never hit the highs of his early performances for Atlantic Records. Like Godard, Brecht or David Byrne, Coleman was as illuminating – if not sometimes moreso – when theorizing his own project, as he was in the project itself. Indeed, the man was so on point, that no less than Jacques Derrida comes off as humble – even insecure – in an interview that he conducted with Coleman in 1997. After an awkward mouthful attempting to make Derridean sense of improvisation’s dialectic of repetition and rupture, the comrade with the saxophone said to the French philosopher: “Repetition is as natural as the fact that the earth rotates.”

Derrida clearly seemed interested in Coleman’s dictum of “harmolodics” which decenters the specificity of tone. Decentering tone, however, was grounded in what Coleman referred to as “punching the C.” Every musician has their own “movable C,” understood as a tone, a note, a timbre, a sound that was related to another tone, note, timbre – that is to say, a sort of determinate negation. That repetition, that ideational presence of structure in a seemingly formless void is always-already present when sound is produced, or when social time is measured in a sense that sound become what we know as “music.” This is perhaps why one of the most satisfying moments for listeners of improvised music – jazz, rock, bluegrass or post-rock – is the segue or the re-entry of improvisation back into the chord pattern and metre of the composition being explored – the reappearance of the syncopation. The syncopation that confused Adorno exists, after all, even in seemingly un-syncopated temporal parcels of social time.

Derrida clearly seemed interested in Coleman’s dictum of “harmolodics” which decenters the specificity of tone. Decentering tone, however, was grounded in what Coleman referred to as “punching the C.” Every musician has their own “movable C,” understood as a tone, a note, a timbre, a sound that was related to another tone, note, timbre – that is to say, a sort of determinate negation. That repetition, that ideational presence of structure in a seemingly formless void is always-already present when sound is produced, or when social time is measured in a sense that sound become what we know as “music.” This is perhaps why one of the most satisfying moments for listeners of improvised music – jazz, rock, bluegrass or post-rock – is the segue or the re-entry of improvisation back into the chord pattern and metre of the composition being explored – the reappearance of the syncopation. The syncopation that confused Adorno exists, after all, even in seemingly un-syncopated temporal parcels of social time.

Blues, R&B and Bop

Coleman started out playing Rhythm and Blues in his home state of Texas, a veritable musical petri dish. Indeed he once played alongside the legendary King Curtis, whose staccato signature may be well known to those familiar with the theme to Benny Hill or the wonderful saxophone solos on early 45s by the Coasters. The path from blues through R&B and finally to bop was a natural progression for a whole generation of Black musicians in the early fifties. Everyone wanted to be Charlie Parker, no doubt, but you had to learn how to occupy a groove, a specific quantity of measured time constituting what we now think of as a “song.” In turn, within the set parameters of R&B, one had to distinguish oneself within a far stricter syncopation than, say, what was being developed as “cool” jazz by Davis, Evans and more middle-class, trained musicians in New York, L.A. and Chicago.

Moving beyond the chitlin circuit to Los Angeles, Coleman operated elevators while voraciously reading music theory, realizing that notation, scales and harmony were nothing but appearances. They were social relations, rules with which the social ear had been trained to hear a ‘proper’ schema, and that – as such – certain sounds “clash.” In actuality, Coleman was hardly the first to discover this on his own, but it is not so simple as him rejecting notation and so-called “western harmony.” It was that he had a more expansive and dialectical understanding of what can be seen, on one level of abstraction, as one of many modes of exposition for his mode of inquiry. In a sense, this was a political project, he later told Derrida that “sound has a much more democratic relationship to information, because you don’t need the alphabet to understand music.” It would seem that conscious knowledge of one’s “moveable C” was secondary to the ability to listen to each other, to take what already exists – as a composition or as a “vamp” by a rhythm section, and enter an area where musically speaking, the free development of each was the free development of all.

Coleman’s early records, more than anything else testaments to this insight. What can specify good improvisation – however labelled – from mere noise depends on whether the musicians, whether consciously or not, are aware of their “movable C” and thus able to listen to one another. Coleman, and his co-thinkers and collaborators like Don Cherry and the recently departed Charlie Haden were consciously trying to innovate but there was never an aesthetic arrogance to what they were doing, compared with others from this time of aesthetic ferment. Coleman’s first two records pushed boundaries, both in its resuscitation of a very traditional blues framework, his rhythm section almost sounding like it came from Chicago. He and Don Cherry’s experiments at this point were with pitch and playfully provocative – indeed, it can be said without hesitation that at least in the jazz idiom, such rudeness to tradition was the aesthetic equivalent to the development of punk rock. As Thom Jurek of AllMusic puts it, his early Pre-Atlantic records Coleman founded “a people’s groove that only confounded intellectuals.” Intellectuals could “dig” the introduction of modal tuning or the experimentation with textures in the Blue Note camp. But this Coleman guy, whoa – what the hell is he doing?

1959

To aficionados of jazz, 1959 is the year that it really all started to shift. To traditionalists like Ken Burns and Wynton Marsalis, there is an implication that this birth of experimentation was the downfall of their pristine culture of jazz. To those who are moved in a way that cannot be expressed in language, this was the peak of the form as a whole. Including Coleman’s third record, there are at least half a dozen masterpiece records from 1959 – Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue; John Coltrane’s Giant Steps; Charles Mingus’s Mingus Ah Um and its companion piece Mingus Dynasty and the often overlooked debut by hard-bop trumpet player Donald Byrd, Byrd in Hand. There can be no dispute that all of these records are transformational. Some are more mellifluous and easy to listen in what may be called a “chilled out” fashion (Davis, Byrd), while others demand an active listen (Mingus). It is notable that while all of these records were experimental in that they brought new sounds to the jazz idiom that was moving beyond bop and hard bop, all but Byrd imported musical frameworks that had heretofore been foreign to jazz as a whole. Byrd, on the other hand experimented with texture – two saxophones, a drummer who played on the twos when he should have been playing on the ones, that sort of thing.

Then of course, there was Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come. Like Byrd, Coleman’s innovation was endogenous within jazz as a blues-derived form, as compared with the exogenous shifts that came from Mingus, Davis and Coltrane. Indeed, this record is simultaneously incredibly challenging and staunchly traditional. While certainly not the first to do so, the sound of a jazz combo without a piano (or less often, a guitar) playing the chord changes was missing. Even so, one can almost hear that phantom piano as one listens – it is the “moveable C” that provided a set of rules, all the musicians could ‘hear’ it as well, it seems – Don Cherry and Coleman’s anything-but showy improvisations remind one of watching a dance performance without hearing the sound. After a while one starts to hear what one perceives as parcelled out sound that is guiding the movement of the dancer’s bodies.

The song “Lonely Woman” stands to this day as one of the most poignant, even intimate jazz compositions, a sort of blues-for-postwar capitalism, a cold war dirge. Coleman told Derrida: “I came across a gallery where someone had painted a very rich white woman who had absolutely everything that you could desire in life, and she had the most solitary expression in the world. I had never been confronted with such solitude, and when I got back home, I wrote a piece that I called ‘Lonely Woman’.” Like many of the best politically-minded artists of the last half century, Coleman approached the political sideways and was never as publicly connected with the far-left as his colleagues like Haden and Cherry. Nevertheless, this five-minute burst of empathy was radical in every possible way in that it grasped the inherent sadness of late fifties life, yet, like the filmmaker Billy Wilder, for example, never reduced that sadness to some ideological existential mourning of the “human condition.”

Stereo Jazz

Coleman never matched the heights of this record – but two records later, his innovation of Free Jazz was introduced to the world. The record is, quite literally, one forty minute piece of improvised music played by what seems to the listener as two distinct combos coming out of the left and right speaker. Stereo was a new form of mechanical sound reproduction at this time, and indeed most early stereo jazz recordings are far inferior to the “mono” or monaural (one channel) sound, replete with sound separation that feels ‘unnatural’ and processed – this is especially the case in early stereo mixes of Blue Note records. The effect here, with the contribution of legendary producer Nehusi Ertegun, gives the feel that an unedited jam session was actually two separate performances – but then as often as not, one notices that the drummers and bass players are playing in unison. This isn’t to say that the brush-strokes of Billy Higgins and plunk-a-plunk funk of Scot LaFaro on the left and the pounding toms and snares of Ed Blackwell and rule-breaking, nearly guitar-style plucking of Charlie Haden on the right were playing the same exact groove. They were – in combination – the moveable C, though there were times that they would break out. As well, while Coleman was the bandleader, on this record he was one of four unique reed and brass tones, sharing the left channel with Cherry with what Shelby Manne called their “laughing and crying tones,” but on the right you have the mellifluous and quite traditional trumpeter Freddie Hubbard playing alongside perhaps the most adventurous musician on the record, Eric Dolphy squawking away on bass clarinet. Indeed, Dolphy often would subtly trade places with Haden in providing a low, guttural groove.

Unlike what followed, in which the concept of “Free jazz” was taken literally, there was much by the way of conception – by Coleman and his bandmates as well as the producer. Atlantic Records branded this style, packaging the record with a replica of a Jackson Pollack painting on the inside of the gatefold album cover. Later free jazz, with the possible exception of the work Dolphy and John Coltrane engaged in, lost the “moveable C.” While sometimes incredibly interesting, it was often predicated upon the idea that musicians could just play together without listening to each other. Coleman thus spent the rest of his career not so much digging further into a form that he had already perfected. Rather, he spent much of the sixties, into the seventies, experimenting with texture and instrumentation. While never recording the absolute masterworks that he would for Atlantic Records, Coleman’s innovations, both as a theoretician and musician (he played free jazz with symphony orchestras, learned to conduct, played violin, oboe and piano) continued at a steady pace, without interruption, for the last half century.

In the early nineties, Coleman was hanging out backstage, waiting to sit in with the much beloved and much detracted improvisational rock band, the Grateful Dead. Coleman didn’t like what he was hearing. An admirer of Jerry Garcia’s effervescent guitar playing, Coleman had played with him a number of times. But these were the dying days of the junked-out Grateful Dead. Improvisations that once had seemingly unrelated and indeed contradictory had degenerated into six musicians playing whatever was coming into their minds. Not a pretty sight. Listening to this cacophony, Coleman said to the Dead’s manager: “Man, these guys don’t listen to each other when they play.” Yet a listen to a bootleg recording of the concert has Coleman hitting the stage during the Dead’s “space” segment (their own “free jazz” that by the nineties was very much driven by MIDI and electronics). Suddenly, the band sprung to life culminating in a version of Bobby Bland’s “Turn on your Lovelight” – precisely the type of Rhythm and Blues that Coleman played as a kid in Texas. The band was listening to each other again.

Listening. This was the key to Ornette Coleman’s cultural production as a whole. It is easy to romanticize the best improvised music in a quasi-new age sense, that is to say the idea that some type of extra-human intelligence of a sort is channeled at “peak moments.” Indeed, many improvisational musicians, unable to fathom the affect they and their audience experience, take to this kind of belief. It is notable, thus, that Coleman, while sometimes having a foot in the milieu of “spiritual jazz” alongside comrades like Don Cherry and Charlie Haden, never took to such mystification. This mystication is redolent of Frederic Jameson’s point about conspiracy theory, that is to say, the repressed awareness of totality is mystified as conspiracy. Coleman’s “moveable C” and praxeological demystification of the democracy of sound-as-social-time was able to – in a self-aware sense – channel the totality in a fully realized sense. The rational kernel in the mystical shell of invisible music is filled out by the sharp-dressed man with the wailing sax. I’m going to miss him. •

This article was first published on the Red Wedge magazine website.