In the night between April 18th and April 19th a boat filled with up to 950 migrants sank in the Mediterranean Sea, 70 miles north of Libya, while trying to reach the southern European border. This was not only the greatest tragedy to date involving migrants in the Mediterranean Sea, it is also the latest in a long series of deaths: around 14,600 from 1993 to November, 2012; 900 in little more than a year from January, 2014 to April, 2015, before this latest tragedy.

In the face of between 700 and 900 deaths, it is difficult to write a series of numbers and data, when anger, sadness, and shame would seem to be a more appropriate response. Yet, the risk of a merely emotional response is that, after a while, these continuous reports about people starved to death, frozen, or drowned on these miserable boats, trying to reach a far off dream of safety and well-being, will end up anaesthetizing us all, to the point that these deaths will become part of our everyday normality. To avoid ending up feeling nothing, then, it is necessary to understand. And the first thing we should understand is that the migrants coming from Africa and the Middle East, running away from wars and extreme poverty, die in the Mediterranean Sea of hunger, thirst, hypothermia, violence, and shipwrecks, but most importantly, they die of the European Union.

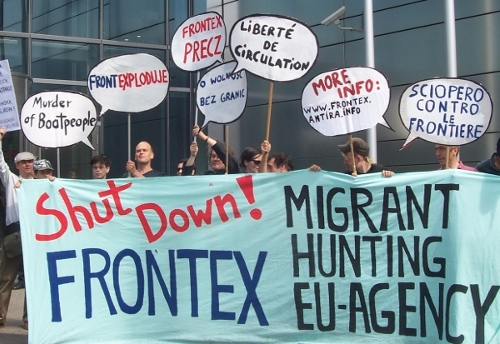

The Creation of Frontex

The number of deaths has seen a decisive increase starting from 2003, reaching a peak in 2011: more than 2500 in a single year, to be contrasted with the less than 500 a year between 1993 and 2001. This significant increase is not fortuitous. It is rather the outcome of specific policies implemented by the European Union for the control of immigration. This process started in 2002, when the European Council of Seville began the process of joint management of migration flows. But the decisive steps arrived in 2004, when exiles’ camps were created outside Europe, European governments reached the first agreements about asylum with Libya, and the European Council created Frontex, the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders, which became operational in October 2005.

Among its various tasks, Frontex is responsible for the coordination of operational border security cooperation among EU States, for assisting the training of border guards, and for operationally and technically assisting EU States in moments of increase of migration flows. Bilateral agreements among EU and non-EU States, for example between Mauritania, Senegal and Spain or between Italy and Libya, have not only allowed Frontex to operate directly within the territory of non-EU States, but also those very non-EU States to participate in the various operations for the patrolling of the Mediterranean Sea. It is important to notice that the participation of non-EU states in these bilateral agreements and in the operations of control, repression, and discipline of migration flows have been implicitly bought through import-export contracts or joint ventures offered to them by EU States.

In spite of the European institutions’ and mainstream media’s efforts to present Frontex as an agency that has as one of the main goals the rescue of migrants who try to cross European borders in dangerous circumstances, as a matter of fact Frontex is nothing but the military longa manus of the European Union for patrolling borders, managing camps outside EU borders, and, to put it simply, keep migrants away from Europe or regulate migration flows according to the interests of European labour markets. As a report by Human Rights Watch stresses:

“Although Frontex has insisted it is less ‘actor’ than ‘coordinator,’ it has quickly developed into a powerful actor that plays a key role in enforcing EU immigration policy. The Frontex budget has grown exponentially in recent years, reflecting this development. From €6.2-million in 2004 (just under $9-million (U.S.)), Frontex’s budget grew to more than €88-million (or over $120-million (U.S.)) in 2010.”

Many of Frontex’s joint maritime operations have as their aim preventing boats with migrants from reaching European borders. This not only prevents asylum seekers from having access to procedural rights that apply in EU territory, but also greatly increases the probability of shipwrecks.

Moreover, not only are there no clear mechanisms for investigating the violation of human rights in joint operations or areas of operation in which Frontex is present, but in some cases Frontex directly participated in activities that were clearly violating basic human rights, for example by cooperating with national authorities in transferring migrants to and detaining migrants in detention facilities in conditions that violate international human rights standards.

The enormous increase in shipwrecks and migrants’ deaths in the Mediterranean Sea in the last years is directly related to the implementation of European immigration policies through Frontex. These deaths are no accidents. They are a mass murder. •

This article first appeared on the www.publicseminar.org website.