CUPE 3903 represents contract faculty, teaching assistants (TA) and graduate assistants at York University in Toronto, Canada. In August 2014, their collective agreement expired. Since then, teaching assistants and graduate assistants went out on legal strike, which is in its third week as of March 16, 2015. There are three core issues they are striking for: 1) protecting tuition indexation, which means if the school raises tuition, it must, as an employer, raises wages in step; (2) better funding for Master’s students, many of whom earn $0 dollar paycheques each month; and (3) LGBTQ employment equity.

CUPE local 3903 joined U of T’s educational workers (CUPE 3902) in a strike that now affect two of Canada’s largest universities and involves nearly 10,000 student-workers. This is purely a student strike and reflects a brewing student movement in Toronto. Undergraduate support has been staunch, with hundreds occupying the York’s senate chambers and thousands signing petition pledging support for their striking TAs. Calls for abolishing tuition are more audible by the day. Indeed, other locals across North America are voicing support and an anti-tuition rally is scheduled for Saturday, March 21st at 1pm at Dundas Square, which thousands plan on attending.

The below content comes from The Penguin, a strike newspaper created by a collective of CUPE 3903, with help from local 3902. Its purpose was to break down the walls between the campus and society and impress on Torontonians the fact that cuts to all social services are suffocating families like garrote wire around a throat. Transit service is deteriorating, the cost of living is becoming morally odious, education is becoming inaccessible from kindergarten to high school (with mounting school closures) and education is becoming exclusive for the rich and highly-indebted. In these article below, we highlight the common problems students and society face but stress that through broad-based social movements a better city is possible and a better Canada is on the horizon.

On Strike At York University

Instead of teaching undergraduate classes, conducting research, or even attending our own classes, graduate students in CUPE 3903 at York University are out on the picket lines. We’d much rather be in the library or the classroom, but we’ve stopped our work until York agrees to a very simple principle: education must be accessible to everyone.

Access to Education

Whether they are teaching assistants, course directors, or graduate assistants, all of the students in our union have benefitted from something called “tuition indexation.” Simply put, this is a clause in our contract stating that any tuition increase for Master’s and PhD students must be matched by an equal increase in the funding they receive from the university. Our funding comes from our employment contracts, and tuition indexation ensures we don’t do the same work for less money.

Considering that our funding packages, after tuition, already leave us well under the poverty line in a city like Toronto, maintaining tuition indexation is essential. Last year, York decided that tuition indexation no longer applies to new students, and raised annual tuition fees for international graduate students by $7,000. When you compare tuition costs with funding and wages, international students at York barely break even. Tasked with full-time academic work and unable to legally work outside the university, these students are in an impossible situation.

In our current round of bargaining, York has made it clear that they plan to implement major tuition fee increases for all graduate students. Without an increase in funding, York’s plan will push higher education out of reach for most students – at a time when advanced degrees are a requirement for many careers.

On Strike for Future Students

The message this sends to future students is clear. While York claims to value the essential work graduate students do to keep the university running, the administration expects these services to be provided more cheaply by incoming cohorts.

CUPE 3903 has a different vision for the future of our university. We know that high-quality education for undergraduates starts with valuing the work of educators. We know that students from all backgrounds need to be able to complete their work without worrying about how to pay for groceries and rent. We know that LGBTQ students face serious barriers to education, and that an accessible university must provide them with strong equity protections.

Fighting for a Living Wage

Much like our colleagues in CUPE 3902 at the University of Toronto, Master’s students at York know what it feels like to be taken for granted by a prestigious university. After paying tuition, York Master’s students are left with a mere $3,000 to live on for the entire year.

While fixing the Canadian university system means making a commitment to future generations of students, we’re asking York to respect the efforts of the Master’s students that make this university work today. Right now our members are keeping the university afloat with ballooning student loans and part-time jobs. A modest increase in funding would not only ease the financial burden on our members; it would be a much-needed gesture of respect.

For a Better York

Our strike has already produced some important gains. On Monday, March 9th, our contract faculty members reached a settlement when the university agreed to significant improvements in their job security. This is a strong first step towards getting our members back to work, but we all stand united for the rights of teaching and graduate assistants.

Please join us in asking the university to return to the bargaining table and to offer a contract that makes accessible education a priority for all current and future students. Our demands won’t cost the university much, but they’ll make a huge difference in the lives of our members. The sooner we’re back in our classrooms, the sooner we can get to work on building a better York.

On Strike At University of Toronto

While teaching assistants and course instructors at the University of Toronto are responsible for a majority of the teaching at one of Canada’s elite universities, they receive about 3.5 per cent of the university’s $2-billion budget. On strike since February 27th, CUPE 3902 Unit 1 members are eager to get back to work, but they’re waiting for the university to return to bargaining with an offer that actually improves their income.

The university’s proposed wage increase, from $42.05 to $43.73 per hour, seems generous on the surface. Seeing this hourly rate, many Torontonians may wonder what the strike is all about. What Toronto needs to know is that an increase in the hourly wage will not raise the total yearly funding package for most teaching assistants.

Under the terms of the university’s offer, the standard funding package for graduate students remains fixed at $15,000 per year, where it has stood for the past seven years. A wage increase will not increase the overall amount of annual funding teaching assistants receive, because if the salary portion of the funding package increases, the scholarship portion decreases along with it.

Teaching assistants at UofT have one basic, reasonable demand: a funding package that reaches Toronto’s before-tax poverty line of $23,298. Although the university administration budgeted an income surplus of $194-million for 2014-15, they have refused to even consider an increase in funding for their graduate students.

When wealthy universities expect students and staff to live on poverty wages, something is clearly broken in the higher education system in Canada. •

Education Restructuring and Cuts

As strikes at the country’s two largest universities continue, Canadians have begun to wonder: why are York University and the University of Toronto so resistant to providing their graduate students with a fair contract? Part of the responsibility lies with the Ontario government. Increasing tuition fees on indebted and underfunded students isn’t just bad management practice; it’s part of the larger problem of chronic funding shortfalls for post-secondary education in Ontario.

Ontario’s education spending per full-time post-secondary student is the lowest of any Canadian province, and stands 24 per cent below the national average. With the Ontario government spending $3,500 less per student compared to average provincial spending, students in Toronto are left to make up the difference on their own.

Changes to federal policy in the 1990s have also resulted in a 50 per cent decrease in federal funding for post-secondary education. To make matters worse, there is now no mechanism to ensure that federal transfers intended for universities and colleges are actually used for that purpose by provincial governments.

Funding a Better University

With the burden of funding post-secondary education shifting from governments to students and their families, Ontario universities have begun to look for alternative sources of cash. While government coffers seem chronically empty, stock markets continue to post record highs. But the promise of the market is often overstated: over the last ten years, risky investments by both York and UofT have resulted in hundreds of millions in lost education dollars.

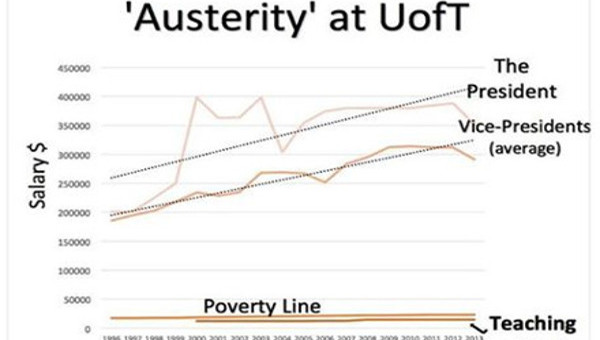

There is no doubt that many of the problems in Canadian higher education are structural. But university management is all too happy to point to the province to explain their budget woes. The detail conveniently left out of their story is administrator salaries. At York, President Shoukri earns $478,405 per year – nearly half a million – while a handful of other top administrators earn well above $300,000. When it comes to paying management, it seems there’s always room in the budget.

In order to fix education in Ontario, the province must find a source of funding that alleviates the burden on those who can least afford to pay. With an 11 per cent reduction in

corporate taxes over the last 15 years costing the province billions in lost revenue, raising the provincial corporate tax rate

would be an obvious place to start. At Ontario universities, another question looms: why not adjunct administrators instead of adjunct or contract faculty? •

The Vicious Cycle of Tuition,

Debt and Unemployment

According to leaders in government and the private sector, a university or college education provides young people with crucial skills for an increasingly demanding job

market. For prospective students, getting a degree or diploma is promoted as both a smart investment in their future and a personal contribution to the challenges facing Canadian society. But how well does this vision of post-secondary education match our current economic reality? What can Ontario youth expect from all their hard work and effort?

The Spiral of Tuition Hikes

The numbers tell a sad story. Since 2006, tuition fees at Ontario universities have skyrocketed by 370 per cent (adjusted for inflation), saddling Ontario students with the most expensive education in Canada. With average tuition costs of $7,539 per year, Ontario students pay nearly triple the fees of their colleagues in Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador.

Thirty years ago, roughly 80 per cent of the average Ontario university’s revenue was covered by government funding. Today, government funding only covers around 46 per cent, and students contribute 41 per cent to the university bottom line. These numbers signal a radical shift to a funding model that has individuals rather than society as a whole bearing the costs of post-secondary education.

The Student Debt Trap

Faced with a demanding course load and a tight job market, most university students are simply unable to pay for the costs of a degree on their own. For Ontario students who need to borrow money to help pay for their education, going to university means racking up an average personal debt of $37,000. In 2012, almost 425,000 students in Canada borrowed money to finance their studies. According to the Canadian Federation of Students, student debt is increasing by $1-million per day – a figure that only takes government student loans to undergraduates into account. When you add graduate students and bank loans to the picture, the figures are even more ominous.

These unsustainable debt levels are contributing to a Canadian household debt bubble bigger than that of the U.K. or the U.S. before the 2007 financial crisis, according to a recent report by the McKinsey Institute. Taken together, Canadians currently owe a total of $1.5-trillion. For Canadian students, paying down their student loans increasingly looks like a lifelong project.

Hard Times in the Labour Market

Turning to the world of work, youth employment numbers aren’t very encouraging either. Currently standing at 15.3 per cent, Ontario’s youth unemployment rate is one of the highest in the country. But unemployment isn’t the only problem; the quality of job opportunities has also taken a big hit since 1990.

There are now more part-time than full-time jobs in Canada. The number of temporary jobs has doubled since 1997, and in many sectors jobs have simply been eliminated. To take manufacturing as an example, the number of youth employed in the sector in 2013 was half the 1990 figure.

To top it all off, wages have stagnated while the cost of living continues to rise. In many cases, wages have even decreased; for youth working in the manufacturing and retail sectors, wages were lower in 2011 than they were in 1990.

Reclaiming the Future

For young people in Ontario, the link between education, hard work, and a decent standard of living is close to the breaking point. Something needs to change if we want a university or college education to mean more than a ticket to a lifetime of debt and low-wage work. Join us in calling on the government of Ontario and universities like York and UofT to make these changes a reality. •

Where Will the Money for Education Come From?

The impression that York University wants to make – that it is struggling to get by, and so any money it spends on teaching assistants and contract workers will come out of the pockets of undergraduate students – is effective but untrue. Before we accept this image of York as a poverty-stricken public institution that just happened to spend more than $1-billion (and still turn a profit) last year, we should consider how they came up with this narrative in the first place.

Climate of Crisis

Creative as they are with branding, this strategy is not a York original. The Ontario government has set a strong example by spending the last several years crafting their own image of a province in fiscal crisis. Whatever “crisis” might exist can be traced to a policy of refusing to discuss things that actually generate revenue, like reversing the misguided cuts carried out by the Harris government, which represent a fiscal loss of nearly $19-billion per year.

Instead, the provincial government, following the suggestions of the 2012 McGuinty government’s Drummond Report, has embraced the spendng-cut approach to “saving” money. While this approach might keep money in government coffers, who does it help in the long run?

For example, cutting full-day kindergarten or the fifth year of high school – among the suggestions in the report – would certainly save money, but what about the long-term social costs associated with less prepared high school graduates or the repercussions of removing child care support for low-income and working families?

We Do Have Choices

Adding just 1 per cent to the marginal income tax rate on the richest 1 per cent of Ontarians could generate potential revenues of $250-million. Expanding that 1 per cent increase to the richest 10 per cent would mean $640-million more. Phasing out the capital tax in 2004 and eliminating it in 2010 has “saved” businesses $2.1-billion.

Clearly, we aren’t limited to choosing which expense or social service to cut, or between fair wages and fair tuition. We can only be convinced of these false choices if we forget that there are other options available. •

Tax Cuts and the Cost of Living

Crisis in Toronto

Even as the number of Toronto millionaires reaches above 118,000, many of the city’s residents are now facing a cost of living crisis. Between 1970 and 2005, the proportion of Toronto designated as “low-income neighbourhoods” grew from 19 per cent to 53 per cent, while “extreme low-income communities” jumped from 1 per cent to 9 per cent. The residents of these neighborhoods are disproportionately racialized, particularly compared with the demographics in wealthy areas downtown.

The Affordable Housing Gap

A lack of access to decent and affordable housing has played a central role in driving this transformation. According to the Ontario Non-Profit Housing Association’s 2014 wait-lists survey, there are some 165,069 people on wait-lists for housing in Ontario, with 38,000 households added to the queue over the last 10 years. Despite an estimated average wait time of 3.89 years, some names have been waiting for up to a decade. These numbers reflect a policy trend – started by past Conservative governments and maintained by Kathleen Wynne’s Liberals – of slashing social programs designed to support low-income families.

At the local level, Rob Ford has similarly slashed housing subsidies. The City of Toronto Shelter Support and Housing Administration took a cut of $137-million in 2012 under Ford’s administration. An additional $128-million was cut in 2013, making for a 33 per cent reduction in two years. Meanwhile, real-estate developers are reaping huge profits from an unprecedented condo-boom that shows few signs of slowing down.

Ripping-off transit riders

For the many Toronto residents who depend on transit, Mayor Ford snarled their daily commute when he slashed 62 routes in 2010. As a result, serious overcrowding is now a permanent feature at peak times. Current Mayor John Tory has followed a similar strategy of making transit riders bear the costs of service improvements with his recent announcement of a TTC fare increase. As many will recall, Tory made promises during his election campaign that TTC fares would remain frozen.

Under the new hikes, a monthly Metropass will now cost $141.50. Fares paid by riders now make up 70-80 per cent of the TTC’s total operating revenues, which is the highest proportion for any transit system in North America.

A Common Cause and a Common Solution

For education workers at York and the University of Toronto, managing housing and transportation costs on a limited fixed income is a serious challenge. Beyond the university, growing numbers of Toronto residents are struggling to pay for their own basic necessities. These problems have a common cause, and we believe they have a common solution. •

Resources:

- CUPE 3903 (York) – 3903.cupe.ca, betteryork.ca, facebook.com/CUPE3903, facebook.com/StudentsForABetterYork.

- CUPE 3902 (UofT) – cupe3902.org, weareuoft.ca, facebook.com/StudentsForCupe3902.

- David Bush and Doug Nesbitt: “Austerity Strangles Ontario: the TA strikes in Context,” The Bullet No. 1088.

- “Solidarity with CUPE 3902 and 3903,” LeftStreamed No. 252.

- Jordy Cummings: “Still striking to win at York University,” Socialist Worker.

- Alan Sears: “Student Power, Worker Activism and the Democratic University,” New Socialist Webzine.

- Alan Sears and James Cairns: “Austerity U: Preparing Students for Precarious Lives,” The Bullet No. 932.

- Jeffrey Noonan: “Win This Strike!,” The Bullet No. 874.

- Chris Dewar and Alex Ramirez: “Class and Conflict in the University Sector,” The Bullet No. 478.

- “Capitalism in the Classroom,” LeftStreamed No. 214.

- Tyler Shipley: “Demanding the Impossible: Struggles for the Future of Post-Secondary Education,” The Bullet No. 215.

- Eric Newstadt: “The Neoliberal University: Looking at the York Strike,” The Bullet No. 165.