As we near 2015, the United Nations (UN) will probably set new objectives on behalf of the global community to supersede the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The MDGs are held largely by the UN, the World Bank and many anti-poverty campaigners, which I label here the anti-poverty consensus, to have been a success. According to the UN, The First MDG – the objective of halving world poverty between 1990 and 2015 – was achieved already in 2010.

U.S. President Barack Obama and UK Prime Minister David Cameron, amongst others, have been arguing for some time now for the total elimination of world poverty by 2030. Who on Earth could possibly fail to celebrate the global community’s achievements to date on poverty alleviation? Who could disagree with the objectives of achieving zero global poverty?

U.S. President Barack Obama and UK Prime Minister David Cameron, amongst others, have been arguing for some time now for the total elimination of world poverty by 2030. Who on Earth could possibly fail to celebrate the global community’s achievements to date on poverty alleviation? Who could disagree with the objectives of achieving zero global poverty?

To see what is wrong with the above proclamations and objectives, we need to view them from a radically different perspective to that of the anti-poverty consensus. To do so we may start by reminding ourselves of the term ‘doublethink’ coined by George Orwell in his dystopic novel 1984. Winston, the novel’s main character defines Doublethink as “To know and not to know, to be conscious of complete truthfulness while telling carefully constructed lies… to use logic against logic, to repudiate morality while laying claim to it…”

Anti-Poverty Consensus

The anti-poverty consensus legitimates the extreme concentration of global wealth in the hands of a tiny minority whilst ideologically justifying continued mass impoverishment. It is an example of doublethink in at least four ways. Firstly, the international poverty line as devised by the World Bank and used by the UN to calculate extreme poverty is $1.25 (U.S.) a day purchasing power parity.

This is an inhumanely low poverty line. If applied to Britain it would be equivalent to 37 people living on a single minimum wage, with no benefits.1

There are other more humane poverty lines. The London-based New Economics Foundation argues for $5 (U.S.) a day.2 World Bank insider Lant Pritchett advocates $10 (U.S.) a day.3 Both would reveal a much higher incidence of world poverty than claimed by the anti-poverty consensus. Pritchett’s calculation shows that 88 per cent of humanity lives in poverty. Martin Ravallion, author of the World Bank’s $1.25 (U.S.) poverty line himself admits that it is extremely conservative.4

This poverty line is invaluable for the anti-poverty consensus because it purports to show how millions are being pulled out of poverty by neoliberal globalization. A higher more humane poverty line would show many billions of people living in poverty with little hope of escape from it under the present development model.

Secondly, the anti-poverty consensus argues that global poverty reduction is best pursued through rapid economic growth. This requires the world’s rich to become much richer before the poor of the world can become a little less poor. It also hides from view the way in which the world’s rich have been increasing their share of global wealth at the expense of the world’s poor.

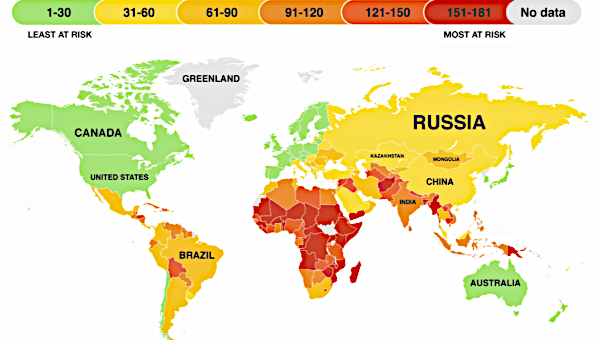

By 2013 the richest 1 per cent of the world controlled $110-trillion, or 65 times the total wealth of the poorest 3.5 billion people.5 This concentration of wealth is based, in part, on the immiseration of the world’s poor. The latter have seen their share of global wealth reduced over the last 30 years through falling wages, reduced social protection, rising unemployment and the privatization and despoliation of natural resources.

Thirdly, the anti-poverty consensus is opposed to reducing inequality, within or between countries. Inequality is not portrayed as contributing to poverty. Re-distribution of wealth and resources is strictly off the political agenda. The wealth of the rich is safe.

The fourth way in which the anti-poverty consensus is an example of doublethink is in its rejection of forms of human development that do not fit into its model of perpetual economic growth and wealth concentration. This denial requires the deligitimization and repression of alternative attempts at pursuing human development, and the forcing of these movement’s members back into poverty. But it is precisely these movements that we should look to if we are concerned with identifying new forms of human development.

Labour-Centred Development

In The Global Development Crisis I propose the concept of Labour-Centred Development based upon the actions of mass movements. Examples include: struggles by landless workers from Brazil to India to gain access to land; attempts by indigenous communities to protect their natural resources from Multi-National companies; mass protests by industrial labourers in China and by South African miners for living wages and improved working conditions; and unemployed workers in Argentina and elsewhere in Latin America taking over and running factories rather than face a life of unemployment and insecurity.

There are examples of attempts at labour-centred development the world over. Each one contains the seed of an alternative mode of human development to that proposed by the anti-poverty consensus. However, they face repression by states and private armies, demonization in the media, and are ignored in much of the professional development studies literature. This is because they potentially threaten the elite view of the world that prioritizes economic growth and wealth concentration over real human development.

These movements embody ideas of development based upon using existing wealth to eliminate poverty and to enhance human abilities and choices, directing production toward human need rather than profit, of sharing and reducing working hours, and ultimately, economic democracy.

These social movements have another thing in their favour compared to the global anti-poverty industry. They are part of the mass of the world’s labouring class, whilst the anti-poverty consensus is led by, and serves, the interests of the world’s elites. But this is why the latter require doublethink – to mask their own self-interest as part of a global common interest. •