The Puzzle Defined

Most developed economies continue to experience fall-out from the financial crisis of 2007-08. The Eurozone has been most ravaged, but the U.S. and UK have not fared much better. After the initial rebound from the most severe crisis, growth in many economies has been decelerating to the point that some are once again contracting in

real terms. At the same time, unemployment remains high – hitting record levels among youth in Europe for example – real incomes are flat for the vast majority, inequality is on the rise and austerity programs targeted at social services are eating further into living standards.

Canada has partly bucked these trends. While the overall growth rate has not returned to pre-crisis levels, it has not done nearly as poorly as that in Europe or even the USA. Other measures of economic well-being do not suggest the level of alarm felt in harder-hit economies. To give two examples, the Canadian unemployment rate has grown relatively modestly and the distribution of gains since the crisis has not been skewed toward the very top to the extreme that it has been in the U.S. and elsewhere. The financial press is increasingly optimistic – just this past week cheering newly-released above-forecast quarterly growth figures – and the Conservative government remains steadfast in touting our supposed economic prudence and resilience.

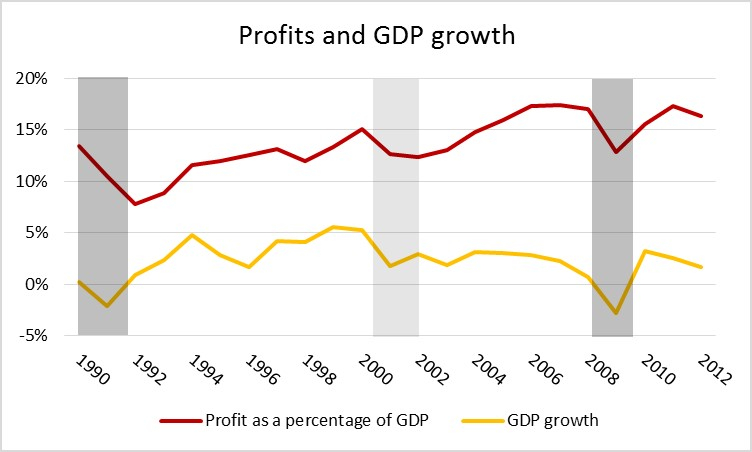

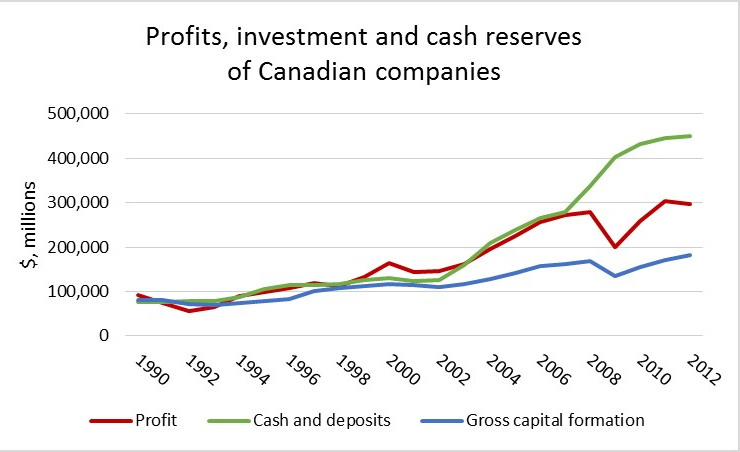

Finally, but not least, Canadian corporations also have had it relatively good since the crisis. Other than a sharp dip around 2008, profits have remained high and growing.

Measured as a percentage of GDP, profit quickly returned to pre-crisis levels, which themselves were higher than anytime over the past two decades.

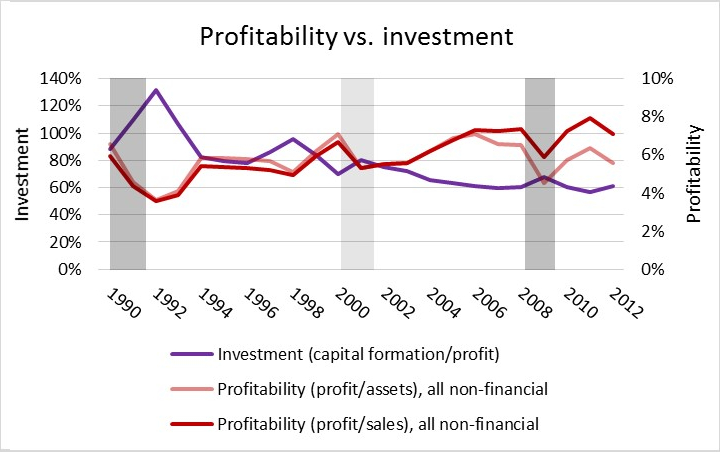

Profitability has similarly recovered, though here the extent varies based on the measure of profitability. Gross profit margins (operating profit divided by sales) have recovered fully. The relatively smaller recovery in returns on assets (operating profit divided by assets)

likely reflects the continuing expansion of asset values – a point I will return to shortly. The continuing high profitability of Canadian companies contrasts sharply with the other developed economies where profitability has not rebounded to pre-crisis levels and remains depressed.

The third measure in Figure 2, however, shows something completely different: the ratio of investment to profits has been falling steadily for the past two decades and now sits at just above 60 per cent. Companies are putting less and less of their earnings back into their stock of buildings, machinery and other equipment – the tools they use to produce goods and services. For every dollar earned before tax, only about 60 cents goes back into maintaining and expanding business capital. Compare this to 80 or more cents just a decade ago. Take

additionally into account the fact that corporate taxes have been cut steadily across Canada for the past two decades – Unifor’s Jim Stanford recently highlighted some of the same trends in Canadian business investment, arguing for the failure of the deep corporate tax cuts to deliver on their promise of boosting investment – and there emerges a picture of a serious investment crisis.

Here, finally, is something Canada shares with other economies that have experienced greater fallout from the financial crisis: sustained falling investment. This is Canada’s profitability puzzle. Our economy has managed to escape the deeper slump suffered by many other developed countries, especially in terms of profit, but also output and, to a lesser extent, employment. We have managed to do so, however, while closely mirroring the stagnation in investment that has accompanied sharper downturns elsewhere. So what is going on?

“Yet rather than invest and despite near-zero interest rates, Canadian corporations have been happy to stash away cash, pay out dividends and consolidate control through share buybacks.”

Government officials and mainstream commentators would likely rephrase this as “what is the big fuss?” The economy is not only growing but picking up steam. We’re doing something right, even if we don’t know what it is. Perhaps the new economy does not require the same levels of investment. Sure, stagnant incomes and unemployment may be problems for some people but these issues will resolve themselves in due course as growth continues. Sadly, this is the same, tired trickle-down theory that has failed the working- and middle-class majority for the past 30 years. This time, however, after the most severe financial crisis since the Great Depression, there are more fundamental questions about our economy lurking in the background.

Profits are the main spur economic activity under capitalism; they are the driving force of the capitalist engine. Capitalist firms exist, in the final analysis, to generate profit. If both profits and profitability are high, then investment should not be in a long-term downward trend. Investment in repairing, upgrading and creating new buildings, machines and technologies is what allows companies to continue to make money. Otherwise these slowly fall apart and profits become compromised. Yet rather than invest and despite near-zero interest rates, Canadian corporations have been happy to stash away cash, pay out dividends and consolidate control through share buybacks. Not only has this benefitted balance sheets and the (predominantly) wealthy owners of business while doing far less for the majority of Canadians, it has produced a profound disjoint. The lack of investment is a worrying sign, but one easily overlooked while other indicators remain relatively healthy.

Pieces of the Puzzle:

Some factors behind our high-profit, low-investment climate

There are a number of factors that are potentially contributing to the disjoint between profitability and investment, none of them particularly sustainable.

One factor is continuing consumption spending by Canadian households. Canadian consumers have been happier to pick up the slack from falling business spending than their counterparts in other countries. The level of household debt as a percentage of GDP in Canada has been rising unabated since the crisis, albeit now at a slower rate than during the explosion of debt between 2001 and 2007. This is another anomaly amongst developed economies, as household debt levels have actually been slowly falling since the crisis most everywhere else. What economists call “deleveraging,” or the destruction of bad debts, has not happened on an aggregate level in Canada and Canadians are simply taking on ever greater amounts of debt, putting themselves at greater risk if things turn sour.

The next factor is closely related and that is the continued growth in asset prices. Debt can keep growing if banks and others believe that the assets which secure debt will continue to increase in value. The main asset owned by many Canadians is housing property. The housing market in Canada never saw the kind of correction experienced by the U.S. and the European countries hit hardest by the crisis. The IMF recently put overvaluation in Canada’s housing market at between 5 and 10 per cent and listed it as one of the larger risks to continued recovery; the organization also noted in a separate publication that house price-to-rent ratios are 85 per cent above average, the highest in the world.

More broadly, there is the danger that asset bubbles have substituted investment

more broadly as sources of profit and growth in the economy. Canada may have been shielded from the full effects of such a change, but the persistent fall in investment may be a warning sign. Although radical economists have long argued that the developed economies may be entering a situation of relatively constant stagnation and slump that can only be broken by inflating short-lived asset bubbles, which inevitably pop and return things to the low-growth, persistent-unemployment status quo, their sentiment is now being echoed more and more broadly, including by mainstream Keynesians.

Then there is the issue of corporate cash. When profits are growing but are not re-invested in the companies that generate them, corporate cash accounts grow. This influx of cash can further exacerbate bubbles as it searches out profits on financial markets. Utilizing profits to increase cash deposits rather than investing them back in businesses can also reflect changes in management that have occurred over the past decades, particularly at publicly-owned companies. As managers have received greater portions of their earnings in the form of shares and other bonuses, greater attention has been paid to stock prices. Cash deposits are useful for policies such as share buybacks that directly impact share prices and as a means to placate investors with higher dividend payments.

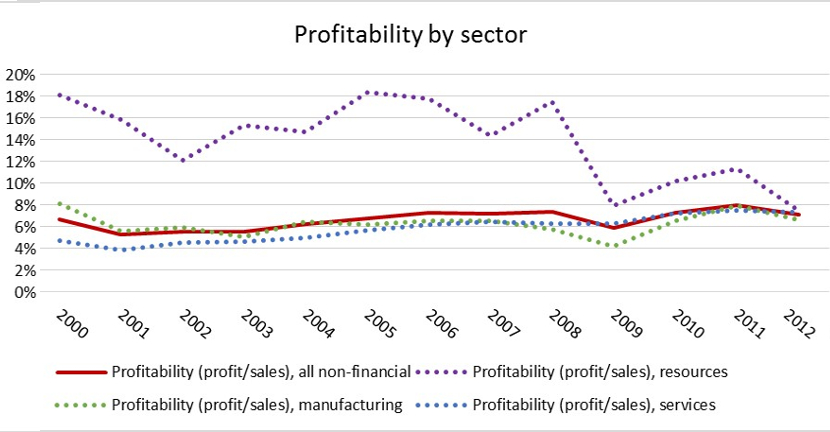

Finally, Canada’s economy is small, open and increasingly resource-dependent. Some final clues may be found in the fall in profitability experienced by the resource sector.

As Figure 3 shows, profitability in resources fell dramatically during the most acute crisis and has remained lower during the recovery. This has happened despite a quick rebound in many global commodity prices. There are many possible reasons for this drop in profitability – too many to explore here – from lower prices on some key commodities to increased competition, particularly from the U.S., to political concerns. Regardless of their source, profitability declines in such a key sector may have disproportionate effects on investment in other sectors.

With the crisis still raging elsewhere, Canadian companies may be simply following global trends in terms of investment and reflecting the economic situation beyond our borders, especially that in the United States. The willingness of Canadian consumers to keep spending, the influx of resource boom profits and some more stringent financial regulations may have all contributed to propping up profitability while investment dropped. Especially if companies are looking beyond our borders when making investment decisions.

Sources of the Puzzle:

Looking beyond the standard account

A gap between strong profitability and dismal investment does not correspond with standard accounts of how the economy functions. According to standard accounts, strong profitability should encourage investment, not depress it further. This theoretical relationship is not borne out in recent Canadian experience.

Beyond the standard account, there are many competing pictures of how such the current puzzling situation can emerge and low private-sector investment can be revived. Here, I want to look at two such pictures and focus on the latter aspect of reviving investment. The first picture comes from Keynes, the second from Marx. I am particularly indebted to Michael Roberts, who has written extensively on the crisis from a UK perspective and who used a similar framework in a recent article (on the adoption of the idea of a permanent slump by mainstream Keynesians).

The two pictures agree on a diagnosis of on-going stagnation – with low investment being just one feature. Indeed, the lack of sustained recovery across much of the developed world has led increasing numbers of mainstream economists to declare that the current slowdown is permanent. Paul Krugman, likely the most prominent Keynesian economist, recently wrote that we may have entered a “permanent slump.” Even the more hawkish Larry Summers has added his voice to the chorus, referring in a recent speech at the IMF to a period of “secular stagnation.” Many Marxist and other radical economists have, of course, been making the same point for years, citing a variety of structural changes and imbalances in the economy, particularly those that characterize the neoliberal period that began in the 1970s when the great post-war boom lost steam.

Demand: The Keynesian way out of the puzzle

While their diagnosis may be similar, Keynesian and Marxian economists see the way out of the current long-term slump rather differently. In general, the Keynesian story is one of weak demand. When the housing bubble burst in the U.S. and other economies in 2007-08, it led to reductions in wealth, employment and income that quickly lowered demand. Only massive injections of money into the majority of developed economies via quantitative easing (QE) stopped a full-blown depression. The problem is that QE has resulted in maintaining interest rates effectively at zero without spurring significant recovery. With near-zero interest rates, the hope is that money should be like a hot potato: costly to hold, moving rapidly from banks who loan it to companies who invest then hire and pay workers who then spend it on consumption resulting in profits that can once again be invested.

This hoped-for virtuous cycle has not quite worked out. Much of the new money has instead gone to equity and real estate markets. The funds that have made it to businesses have served in large part to increase their cash deposits and allowed them to pay out dividends and buyback shares. A significant share of this then also ends up in housing and equity, further driving up asset prices. The flood of cash has increased worries about the growth of new bubbles in both real estate and stock markets across the world.

Unlike the U.S., the UK, the Eurozone or Japan, Canada has not implemented QE. On the other hand, more traditional monetary tools have been sufficient to bring our interest rates in line with the near-zero rates elsewhere. And even without the same quantities of central bank-supplied cash, Canadian companies have been able to follow global trends due to their sustained profitability.

Figure 4 shows how the cash reserves of Canadian companies have ballooned and a recent report by the CLC finds that dividend payouts as a share of profits have also expanded rapidly since 2007. Even without QE, our economy is flush with cash that, given the paucity of business investment, ends up in asset markets. Indeed, Canada recently had the undesirable honour of making Nouriel Roubini’s list of countries susceptible to housing bubbles. Roubini’s claim to fame was, of course, predicting the 2007-08 housing crisis long before it happened.

This rather long detour provides the context to return to the Keynesian solution to inadequate investment. In short, if the problem is inadequate demand, then the solution involves generating new demand. The virtuous cycle of productive investment leading to growth in output, employment and incomes has, however, not restarted despite monetary policy that has sustained interest rates near zero. Since the private sector has been unwilling to undertake investment in capital goods like technology, machinery and buildings to generate jobs and increase output, households continue to face unemployment and stagnant incomes. Households are reluctant to spend, new private sector money goes into financial assets and real estate and demand remains depressed.

If households and businesses cannot be counted on to increase demand, the only sector left is government. Direct government spending via infrastructure investment and expanded social programs is the Keynesian solution to stagnant private investment. Once the reserves of unemployed labour and unproductive capital are put to use by government, there is hope that the private sector will begin to invest again. Rather than businesses putting money into assets, Keynesians count on them seeing new outlets for their products – demand coming from both direct government spending and the incomes of those employed in government projects – thus spurring investment in productive capital. In the Keynesian version, renewed investment-led growth ultimately happens in virtue of human psychology. Optimism about the future and the vision of profit to be made drives the “animal spirits” of business owners. The end result is a virtuous cycle of investment driven by optimism.

Destruction:

The Marxian way out of the puzzle

The Marxian picture, on the other hand, gives priority to profit. If profit drives the capitalist engine, then when it falters, so does the whole machine. Inadequate investment in non-financial capital is a sign that the profitability of undertaking such investment is too low, especially as compared to the profitability of speculative investment in assets. What matters is not so much then the absolute level of profitability but the profitability of new capital whether it is applied to production (most broadly, of goods or services) or speculation. This can help explain the profitability puzzle in Canada and unite the Canadian investment trends with those in economies experiencing even deeper stagnation. Growing asset bubbles in economies like Canada’s that escaped the last crisis relatively unscathed can yet depress investment.

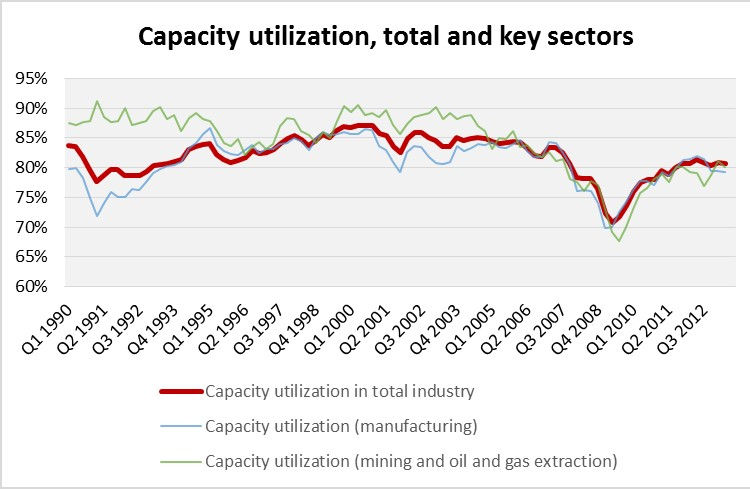

Other factors that can hamper the profitability of new productive capital include

overcapacity – too much capital sitting idle that makes new investment redundant – new technology – greater research costs and greater risks – and debt stemming from existing capital. Perhaps Schumpeter – incidentally no friend of Marxian economics – summed it up best, calling capitalism the system of “creative destruction.” While high profitability is often associated with much of both parts of this definition, the sources of low profitability often boil down to their lack. The Second World War and its aftermath illustrate this perfectly: the destruction of so much productive capacity combined with intense wartime innovation laid the foundation for a 20-year prosperity based on rebuilding and the transfer of wartime technology into the consumer sector. This produced not only two decades of not only high profitability but sustained investment and growth.

Today, on the other hand, we are witness to an explosion of creativity on the side of speculative investment and a growing mass of productive capital that has not been destroyed.

Capacity utilization has been slowly falling in Canada: evidence that a surplus of idle productive capital makes new investment relatively unprofitable, even in the resource sector. On the Marxian picture, without the destruction of some of this idle stock or some other means that impacts relative profitability across the uses of capital, even renewed demand may not be enough to generate significant new productive investment.

On the one hand, the Marxian picture may be more fatalistic than the Keynesian. On the other, overcapacity provides opportunities for more transformative steps on a local level. Take the example of the recently-closed Heinz factory in Leamington, Ontario. Sold off and slated to be closed by its new owners, the idle factory could be taken over by its former workers and transformed into a co-op. While such a co-op would still have to function within the capitalist system, the conditions for its viability would not be exactly the same as those for a capitalist enterprise. In addition, the economic democracy instituted by a workers’ co-operative is a potential stepping stone to more profound economic change.

The question, then, is whether demand or destruction are what is needed to spur investment and reinstitute a growth regime not based on asset bubbles. The answer, in the short term, is likely some mixture of the two. The obstacles to both are, however, substantial. The wholesale destruction of capital has, until now, been made possible by external circumstances such as war – something not on the horizon. Transformative, institutional change, on the other hand, is politically unattainable on a large scale in the short term. The Keynesian solution is also politically problematic in the current climate: the funds for any significant government spending program will eat into profits one way or another.

Puzzle Solved: Austerity gives profits a boost

At this point, however, the Conservative government’s answer to the same question of what is needed is neither; instead, the government proposes a third alternative: deleveraging. This is a fancy “d”-word for austerity or, rather, the lowering of public debt, which is the aim of austerity. The austerity agenda is a political tool with strong economic foundations. The profitability puzzle may be no mystery after all; it is an intentional strategy to ensure the private sector gain with no pain, high profitability with low investment.

Austerity is not an isolated Canadian phenomenon nor is it a new one. The neoliberal era that began sometime in the 1970s has seen austerity in one form or another applied worldwide. Economic crises have especially provided governments with excuses to institute or continue austerity policies that would not have been difficult to institute otherwise. While Canada did not experience the latest economic crisis to the same extent as a number of other countries, it has seen a more moderate version of many of the same trends – such as slower growth and lower employment. The crisis was large enough to allow the Harper government to continue and deepen a tentative austerity regime. While Canada has not pursued austerity programs as spectacular as some, for example the UK or Spain, the Conservative government has,

nevertheless, succeeded in substantially reducing the size of government, small cut by small cut. While Canadian austerity policies predate the crisis, the crisis has only helped to entrench them and further orient them toward propping up profitability.

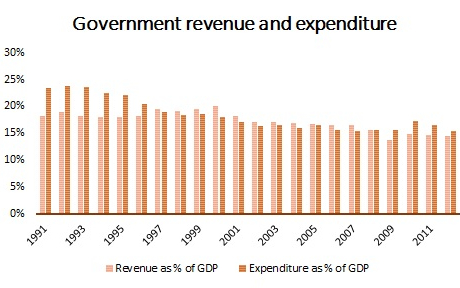

For over two decades, Canadian government expenditures have been falling steadily as programs and thousands of public service jobs have been cut across departments.

The drop in expenditures has allowed the government to cut revenues at the same time and still remain within striking distance of the neoliberal imperative for balanced budgets. Although a number of taxes have been cut, the most stunning has been the fall in corporate tax rates – from 28 per cent in 2000 to a paltry 15 per cent at present. Despite this enormous tax break as well as significant cuts to government spending and income and a forecast to balance the books by 2015, austerity has done little to stimulate private sector investment. The government “getting out of the way” of the private sector has simply left a great big hole that business seems to have no intention of filling. There is, however, a method to this madness.

When Jim Flaherty claims that austerity is working, he is telling the truth. The inaccuracy appears when he says that austerity is working because it has kept Canada from experiencing a more significant economic downturn. Austerity, as so many commentators (Will Hutton, John Cassidy, Sally Kohn) have pointed out, has failed utterly in its stated aims of reviving growth, investment and employment everywhere it has been applied. It has succeed in accomplishing other goals. In the most crisis-ridden countries like Greece and Portugal, austerity has allowed governments to keep paying their creditors even as the population is driven closer and closer to the brink of abject poverty. In Canada, on the other hand, austerity has allowed the corporate sector to maintain high profitability without investing or expanding stable employment.

For the corporate sector, the proposition is a pretty good one: if the government can help us maintain high profits without renewed investment, then why bother investing? Indeed, investment is a risky undertaking. Austerity, on the other hand, is a sure-fire strategy for transferring wealth upwards and risk downwards in the income distribution. There are myriad mechanisms at work to effect this redistribution.

Take corporate tax cuts for instance. These are in reality tax cuts for the rich who (predominantly) own corporations. With lower taxes, corporations have extra cash to pay out higher dividends or invest in a variety of financial assets, including stocks and real estate (remember, there is no need to invest in productive capacity!). These assets are, again, largely owned by the rich and it is they who have the most to gain from higher asset prices. In addition, there is no need to worry about the inevitable correction or crash, as recent history shows that corporations, banks and the wealthy will be bailed out by governments. And when the dust settles, they will be the ones with enough left over to buy up the few assets that the now-poorer middle class and poor will be selling off to make it through.

Cuts to government services, on the other hand, can make space for the private sector to provide some of these same slashed services. The transfer of wealth can occur outright via privatization or indirectly, as when private companies fill the gaps left behind when the government stops providing a service. These mechanisms and others amount to the same neoliberal story of privatizing gains and socializing risks and losses.

It is telling which department and agencies are not subject to budget cuts. For example, the CSEC, Canada’s high-tech spy network, is receiving more funds than forecast. This increase, however, makes perfect sense in light of the recent revelations that Canada is conducting widespread economic espionage – targeting, amongst others, the Brazilian government. Why risk the little investment there is in uncertain ventures when you can get the government to spy for you and rig the game in your favour? Although not directly part of the austerity agenda, this is yet another example of government helping to sustain the high profit, low investment status quo.

The strategy of maintaining high profitability and low investment via austerity also has effects on the majority of the population through (un)employment and debt loads. With low investment, fewer jobs – and even fewer good jobs – are being created. While the official unemployment rate has fallen since the depths of the crisis, at 7.2 per cent it remains higher than it has been most of the past decade. However, taking into account underemployment and discouraged workers, this official unemployment rate is off by roughly a factor of two. Meanwhile, the employment rate, or the percentage of Canadians who do hold a job, fell off sharply after the crisis and has not recovered; it is the same as it was a decade ago and much lower than at its recent peak. Of the jobs that are being created, the vast majority are in the lowest-paid occupations, often precarious, and many of them are also part-time – another way that risks are socialized.

Government austerity also means that everyone pitches in and takes on debt to keep profitability high. Canadian household debt has kept up its rapid growth throughout the crisis and its aftermath. It now stands at 95 per cent of GDP, higher than in both the U.S. and the UK. Meanwhile, corporate debt has fallen from above 60 per cent of GDP in 1990 to just over 50 per cent today. Add to this the explosion of corporate cash holdings and it turns out that Canadian companies have the safety cushion and rainy-day fund that most Canadian families lack. Household debt rather than rising incomes brought about by productivity-enhancing investment is fuelling consumption and, to an extent, rising asset prices. When things go wrong – and in this unsustainable model they inevitably do – the result for many middle- and lower-income Canadians will be financial hardship and higher unemployment.

As noted at the beginning, the Harper government has chosen to follow neither demand stimulation nor industrial policy to solve the problem of slumping investment. Instead, it has pursued austerity, helping maintain corporate profits through a variety of mechanisms that impact on everything from government services to household debt to employment. Government discipline in the name of austerity has produced other kinds of discipline for households: the discipline of precarious work or, worse, the unemployment line, the discipline of debt repayment and, ultimately if necessary, the discipline of the dwindling welfare cheque. Investment can remain in a slump because the private sector is let off the hook – not by chance, but by design.

So, while profitability and growth have remained stable in Canada since the crisis, allowing the government to brag while implementing austerity measures, low investment has managed to largely sneak under the radar. Yet high profits and low investment are not the hallmarks of long-term, sustainable growth. Instead, they are a troubling sign of the bubble economics that was supposed to have largely bypassed Canada. For now, lagging investment has not made itself felt. Somebody is still making money… except it’s just probably not you. •