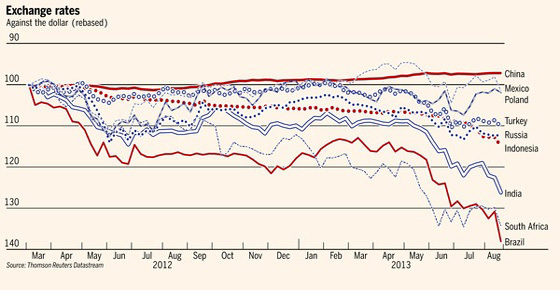

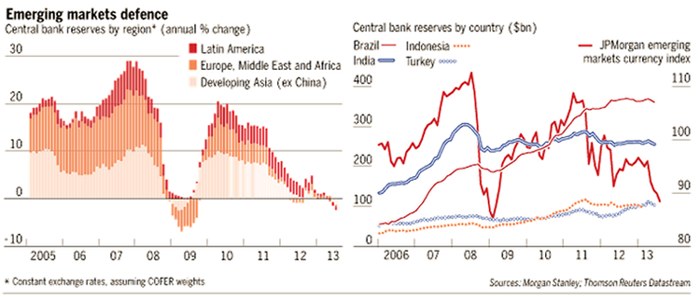

Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Turkey are encountering significant economic turbulence. Since late 2008, the U.S. Federal Reserve has been pumping liquidity into financial markets, amounting to $85-billion a month since last December.1 The cheap money enabled by low short and long term interest rates flooded into “emerging markets” with the expectations for higher returns by financial capital from this ‘carry trade.’ Thanks to capital inflows and low borrowing costs, emerging markets have been able to score high rates of growth and finance their deficits. When the Fed signalled the end of its ultra loose monetary policy in late May, however, capital flows began to reverse and return to the U.S. and other core states. The capital markets in emerging countries have registered around $1.5-trillion outflows since May.2 Due to the outflows and currency market interventions, central banks in the developing world have lost $81-billion of reserves.3 National currencies devalued by 22 per cent in Brazil, 20.4 per cent in India, 14 per cent in South Africa, 11.5 per cent in Indonesia, and 11.1 per cent in Turkey.4

Turkey is one of the economies hit the hardest. The Turkish state has moved to stem the depreciation of the Turkish lira through increasing overnight lending rate and forex auctions. Since early June, the central bank has spent 15 per cent of its net reserves.5 But the lira has continued to free fall to a record low of 2.04 per dollar and 10-year bond yields surged to above 10 per cent for the first time in 19 months.6

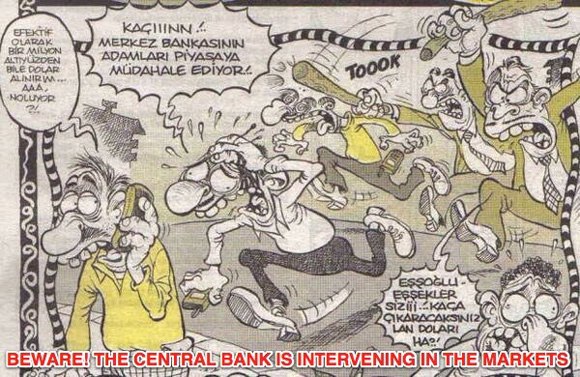

Economists and investors alike have been pressuring the central bank to increase interest rates and shift back to orthodox monetary policy instruments rather than using the confusing system of an ‘interest rate corridor.’ In fact, the Bank of Turkey has a limited toolset. Its total reserves are around $137-billion, compared to Brazil’s $372-billion,7 and less than $50-billion is available for its dollar auctions.8 In other words, it is incapable of following the path of Brazil, which has responded to the turmoil by announcing a $60-billion currency intervention program. The Bank has also been so far reluctant to hike interest rates and slow down growth. Instead, Erdem Basci, the governor of the Central Bank promised to “defend the lira like lions” whereas Caglayan, the minister of economy advocated just “letting it go.” The Bank’s administration has close ties with the Erdogan government which, in the context of political unrest, aims to keep its 4 per cent growth target even if skyrocketing inflation is the price to pay.

Optimism Vanquished

The policy makers and their supporters are optimistic. They celebrate minor increases in net exports that will result from depreciated lira and hope that the enormous current account deficit of $153.6-billion, or 6.8 per cent of Turkey’s GDP, will diminish. Nevertheless, gone are the days of hyper-optimist talk of a ‘lira zone’ as an alternative to the Euro Zone.9 Instead, the government is resorting to statistical games to defend its economic record. The Minister of Economy, for instance, has insisted that Turkey’s GDP is up by 350 per cent since the AKP (Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi, Justice and Development Party) came to power in 2002. However, the exact figure is 63 per cent when calculated in real values not in nominal terms (and 43 per cent growth on a GDP per capita basis). This matches up to the average of Turkey’s high growth period between 1960 and 1978, and exceeds the world growth average today. However, it is beneath the average for just the developing countries, to the AKP’s surprise.10

The picture for the Turkish economy is, indeed, gloomy. There has been a surge in corporate borrowing since the AKP came to power, making the net external debt $413-billion or 51 per cent of the country’s GDP. The debt servicing costs of private firms will rise as the lira depreciates and their profitability will deteriorate. The costs of imports will also increase, which will put added pressure on Turkey’s energy bill, already standing at about $60.11-billion for energy related imports.11 The short term capital inflows used to finance the current account deficit are now withdrawing. This will also impact the bulge in government budget deficits (now at $16-billion in 2012), with mass privatizations no longer available to aid state revenues.

If all this was not enough, Turkey is encountering the consequences of its aggressive foreign policy in the Middle East. For example, the Federation of Egyptian Chambers of Commerce suspended relations with Turkey on Tuesday to protest Erdogan’s position on the overthrow of the Morsi government.12 The Abu Dhabi National Energy Company, Taqa, recently announced its plans to pull $12-billion in investment plans from Turkey.13 Souring relations with Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates over Turkey’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt is also hurting Turkish capital. As demand from the European Union declined with austerity measures, Turkish manufacturers turned to export markets in the Middle East. Capital flows from the Arab countries had already been pouring into the Turkish real estate and construction sectors, the key engines of growth in recent years, and increased trade ties have been following.

Although the Turkish economy is clearly at a critical juncture, the institutional capacity of the Turkish state for managing the crisis in favour of the capitalist classes and placing the burden of adjustment on the working classes arguably has increased. Still, the massive revolt of June is haunting the centers of political power. Although, the participation of the working-class organizations in the protests remained limited, and the energy of the protesters has yet to be channelled into an organized anti-capitalist movement, Turkish policy makers know a significant degree of political opposition exists, and needs to be taken into consideration when making their economic plans.

False Directions

Two types of reactions against the economic turmoil should be discounted. First, the neoliberal critics of the monetary policy have attacked the central bank for its unorthodox and complex interest policy while demanding higher interests rates. The bank is criticized for its lack of autonomy from the government and its growth-obsessed preference over interest hikes.14 Although these views have a point, they fail to address the alienation of the Bank from public debate, accountability and control, and that this is a common trait of the central banks in all capitalist states today (and has increased since the crisis).15 Furthermore, the policy repertoire of the Turkish central bank is circumscribed by Turkey’s place in the hierarchy of states and the way it has integrated into the global capitalism. It is not plausible to leave economic policy dominated almost exclusively by the monetary authorities.

Second, Turkey’s growth strategy since the 2001 crisis (the AKP becoming the ruling party in 2002) is criticized for its preference of foreign funds over domestic savings; short term capital inflows over foreign direct investment; domestic consumption over investment, technological transfers, and industrial exports; and the financial sector over real economy.16 Such an orientation to social democratic economic policies are capable, if in a limited way in the current context, of steering toward a higher value-creating economy and more egalitarian wealth distribution.

However, such policies are always the product of public pressures and social movements, not those of visionary capitalists and a wilful Turkish capitalist state. And today they require the wholesale defeat of neoliberalism inside the Turkish state, and a vastly different international correlation of forces than presently exists. The revolt in June showed that there are many people who are disenchanted by capitalism itself, not merely by a set of capitalist policies. The people are increasingly becoming aware that an aspirin won’t cure cancer. But an alternate treatment will require a rebuilding of a viable organized Turkish left that is just beginning to show the signs of rebirth. •

* Re the title… reference to “Peace at Home, Peace in the World,” a famous phrase of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk (the founding leader of the Turkish Republic) that was later accepted as the motto of Turkey’s foreign relations.