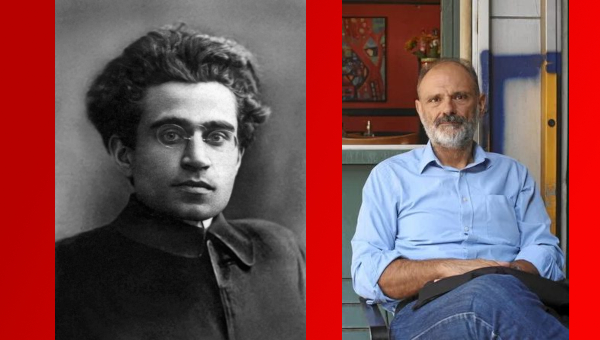

In just the last few weeks, the radical left has lost two of its most important, elegant and eccentric voices, Alexander Cockburn and Gore Vidal. Much (virtual) ink has already been spilled about the manifold aspects of their careers. To be an unabashed cliché monger, Cockburn and Vidal were men of the twentieth century to be sure, but in many ways men of the 19th century. Cockburn, as a journalist was not unlike Marx, decoding the minutae of world affairs in stylish and often very funny prose.[1] Vidal, as Richard Seymour has recently pointed out,[2] was not unlike Oscar Wilde, an acerbic critic on the inside of the ruling class. In lieu of a complete overview, this article seeks to make the case for the importance of radical – and accessible – journalism, and how much Vidal and Cockburn will be missed in the post-print epoch.

Indeed, on one hand, there’s never been a better time to access information, though there’s certainly a lot of disinformation out there. Yet with the plethora of blogs and ‘first take’ journalism, a penchant for moralism and scolding tones and/or saccharine spirit lifting, one is hard-pressed to find a popular Left writer of even an iota of the calibre of Cockburn and Vidal. Indeed, up to the end of their careers – in Cockburn’s case, merely days before his passing, they were still at it with style, Cockburn flaying the Occupy movement for failing to build radical organizations.[3] Contrast that to left-opinion writing in most left or mainstream venues. There is very little humour or zest, with some exceptions. There is not a welcoming tone toward the reader, instead there is a language of initiates. This is not to take away from the plethora of great and accessible radical venues, including The Bullet. This is merely to make the point that the style of writing, of essays, of polemic, engaged in by Vidal, Cockburn and precious few others, seems to be a dying breed.[4]

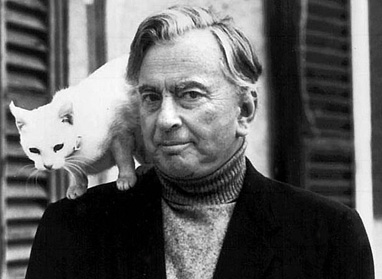

Vidal: Literary Essayist

Let’s just cite a few of their achievements – take Vidal‘s pioneering queer literature,[5] dozen or more Hollywood screenplays,[6] and over half a century as one of the best literary essayists the English language has ever produced, finding socialism implied in the books of L. Frank Baum, flaying the Kennedys, admiring Nasser. While not a Marxist, Vidal knew to historicize. He contextualized the actions of Timothy McVeigh and Al Qaida alike without for a moment condoning their deeds. Indeed, one of his great moments, and one that built his post 9/11 reputation as the scourge of the neocons, was an essay in which he contextualized 9/11 as thus:

“It seems forgotten by our amnesiac media that we once energetically supported Saddam Hussein in Iraq’s war against Iran and so he thought, not unnaturally, that we wouldn’t mind his taking over Kuwait’s filling stations. Overnight our employee became Satan – and so remains…. Our imperial disdain for the lesser breeds did not go unnoticed by the latest educated generation of Saudi Arabians, and by their evolving leader, Osama bin Laden, whose moment came in 2001 when a weak American president took office in questionable circumstances.”[7]

These words, written for Vanity Fair, were refused publication. Vanity Fair had previously published his contextualization of McVeigh, perhaps one of the most powerful works ever written in understanding the relationship between neoliberal austerity measures and the rise of right-wing populist movements, and foretelling of the violent turn these movements took in the nineties. Vidal, along with Cockburn, was among the few on the Left who raised the alarm over the growing executive power deployed by Clinton, the attack on Waco that so alarmed the right and became a rallying cry. Indeed, both pointed out that the Patriot Act, imposed by Bush and his cronies, was a logical continuation of Clinton’s own ‘anti-terrorism’ policies. Vidal indeed struck up a correspondence with McVeigh that a less courageous writer would not have dared, and was even a witness to his execution by the American state. The long piece that came out of their correspondence, provoked by McVeigh contacting Vidal after reading his work on the growth of the security state, is likely one of Vidal’s crowning achievements, combining analysis of the government’s case against McVeigh, personal takes on their correspondence and contextualizing McVeigh’s act against the ongoing “harvest of shame” against Midwestern American farmers as well as “de-industrialization.”[8]

“Asked why he had not at least said that he was sorry for the murder of innocents, he said that he could say it but he would not have meant it. He was a soldier in a war, not of his making. This was Henleyesque. One biographer described him as honest to a fault. McVeigh had also noted that Harry Truman had never said that he was sorry about dropping two atomic bombs on an already defeated Japan, killing around 200,000 people, mostly collateral women and children. Media howled that that was wartime. But McVeigh considered himself, rightly or wrongly, at war, too. Incidentally, the inexorable beatification of Harry Truman is now an important aspect of our evolving imperial system. It is widely believed that the bombs were dropped to save American lives. This is not true. The bombs were dropped to frighten our new enemy, Stalin.”[9]

Vidal was a standard left-liberal in the 1950s, which would be taken as social-democratic in today’s hollowed out political landscape. He even ran for congress in 1960 (and for that matter, the senate in 1982). Seeing the inner workings of Washington forever altered his view of the possibility of liberal reforms through the state, and this point was first manifested in his excellent play, The Best Man, which is enjoying a revival right now, and was made into an excellent film. His attitude toward liberal politicians as essentially weak and servile, if well-meaning and confused, was captured in his performance (as an actor) in Tim Robbins’ satire, Bob Roberts, in which he plays a liberal Democratic senator fighting to retain his senate seat against Robbins’ new-right hero.

Of course, Gore Vidal was an aristocrat who had lifelong contempt for his own ruling class whilst enjoying all of its privilege – or how about that great good spat he had on TV with William F. Buckley Jr. on Firing Line during the Chicago 1968 Democratic convention. In the face of the famous reactionary Buckley’s McCarthyite smears and sneering aristocratic hypocritical homophobia,[10] Gore called the tactics used against Democratic Convention protesters “crypto-fascist,” along with Buckly’s defense of these tactics, and what is more, offered what can only be interpreted as a forthright defense of the Vietnamese revolutionaries, prompting the angry Buckley to lash out with a homophobic epithet and threats of violence. This brief television clip encapsulates so much about Vidal, the American aristocrat, an inconvenient relation to Al Gore, taking his argument with a fellow notable beyond an argument ‘within the family,’ not flinching in the face of the slings and taunts of a cowering Buckley.

Cockburn: Oxonian Marxist

If anything captured the greatness of Cockburn in a similar fashion, it is a classic critique of bourgeois media he wrote for Harper‘s (and re-printed in Corruptions of Empire), centred around the venerable ‘serious’ PBS news programme, the McNeill/Lehrer news report. Satirizing the “two sides of every story” news programming style, Cockburn wrote fictional scenarios of Robert McNeill and Jim Lehrer debating and seeing both sides of the story of the crucifixion, slavery and other historical episodes. Previously, after arriving from the UK as an Oxonian Marxist with a lifelong connection to the Verso/New Left Review community, he took up a column in the Village Voice, that as James Wolcott recently pointed out, virtually invented media criticism, now the nightly practice of Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert. The pinnacle of this line of writing was the Harper‘s piece. The point here was politically pedagogical, in a very Gramscian sense, as well as a roaring good read.

“The McNeill/Lehrer report started in October 1975, in the aftermath of Watergate. It was a show dedicated to the proposition that there are two sides to every question, a valuable corrective in a period when the American people had finally decided that there were absolutely and definitely not two sides to every question. Nixon was a crook who had rightly been driven from office; corporations were often headed by crooks who carried hot money around in suitcases; federal officials were crooks who broke the law on the say-so of the president. It was a dangerous moment, for a citizenry suddenly imbued with the notion that there is not only a thesis and antithesis, but also a synthesis, is a citizenry capable of all manner of harm to the harmonious motions of the status quo.”[11]

Cockburn was never a ‘vulgar Marxist’ or a conspiracy theorist; indeed, he made great sport of disproving the ravings of 9/11 truthers as much as he flayed Oliver Stone and the JFK mythologists in the pages of The Nation in the early 90s (found in his The Golden Age Is In Us). To Cockburn, JFK was the man who started the Vietnam war, assassinated Lumumba and repeatedly attempted to assassinate Castro. So it mattered little whether he was killed by a conspiracy or by a lone gunman.[12] As opposed to a conspiracist or ‘elitist’ worldview, Cockburn’s weltanschaung always contained a clear class analysis. On the day of September 11, Cockburn with his co-editor Jeffrey St. Clair wrote “Who Saw It Coming?”:

“’Freedom,’ said George Bush in Sarasota in the first sentence of his first reaction, ‘was attacked this morning by a faceless coward.’ That properly represents the stupidity and blindness of almost all Tuesday’s mainstream political commentary. By contrast, the commentary on economic consequences was informative and sophisticated. Worst hit: the insurance industry. Likely outfall in the short-term: hiked energy prices, a further drop in global stock markets. George Bush will have no trouble in raiding the famous lock-box, using Social Security Trust Funds to give more money to the Defense Department. That about sums it up. Three planes are successfully steered into three of America’s most conspicuous buildings and America’s response will be to put more money in missile defense as a way of bolstering the economy.”[13]

If one were to go through Cockburn’s entire written oeuvre, from CounterPunch and New Left Review to House and Garden and the house organ of the American Film Institute, a red thread connects all of it. When he visits the set of “Top Gun,” (found in Corruptions of Empire) he finds some of the most interesting and telling examples of the American ideology. Here we see a young Tom Cruise denying vociferously that it’s anything like a Rambo film. Indeed, here we see a young Tom Cruise as a budding anti-capitalist who doesn’t see anything inherently jingoistic or imperialistic in the glamorization of the life of the F-14 pilot.

Later, he interviews some of the F-14 pilots themselves who hold a similar ideology: a common phrase among such pilots is that it is like “sex in a car wreck.” Indeed the ideological mythology of the rugged individualist, Robinson Crusoe on a war machine are all part and parcel of the empire. Yet even this ideology, whether of the class structure of the military or of the iconoclast conquering his fears can be peeled away. Cockburn interviews a weapons designer in D.C. who points out the entire F-14 craze is a creature of the military industrial complex, a big boon for the weapons manufacturers. But in the context of combat, “a total turkey of a fighter… from a floating fortress that’s as obsolete as cavalry and which will be at the bottom of the sea in the first three days of any war.”[14]

Cockburn, alone or with writing partners, wrote a number of books that have stood the test of time. Al Gore: A User’s Manual (written with Jeffrey St. Clair in 2000) is a searing account of Gore’s hypocrisy and dishonesty as, for example, in his tearful speech at the Democratic convention about his sister’s death from lung cancer. In this speech, Gore claimed after that he was through with growing tobacco; in reality, his family held onto their tobacco interests for several years afterwards. Gore’s environmentalism is at best green capitalism, and his arguments are often pro-nuclear and Malthusian.

Cockburn’s co-edited Imperial Crusades (2004), featuring a who’s who of left writers, journalists and theorists, is perhaps the finest “as it happened” documentation of the early years of Bush’s adventurism. Perhaps his best book, however, is The Golden Age Is In Us, (1995). It contains what appear to be all of his notes from 1987 to 1994, many of which were carved into columns, others more personal, about family, his mother’s death, living in a motel. There are wonderful cameos from the likes of Robert Pollin, Paul Sweezy, Paul Baran, and Noam Chomsky. There is a controversial contextualization of Cockburn’s now less controversial view that the end of “really existing socialism” was not neccesarily something to be defended and may well prove disastrous to revolutionary forces in the developing world, dependent upon Soviet material support. He in turn prints letters in response to his arguments and rebuts them. All the way through, we see thoughts in motion, an idea from one note becomes a column which provokes more personal ruminations and thus another column and so on. There is a comment on French economic affairs followed by a rumination on Robespierre and how he (Cockburn) keeps a bust of him on his desk. The funniest moment, however, in The Golden Age Is In Us, however, involves one of Cockburn’s great foils, Ronald Reagan in a moment of glorious dialectic:

“Reagan’s emergence as a Leninist has caused some surprise and irritation in the capital. Lou Cannon was interviewing him for The Washington Post last week and asked whether Gorbachev was really and truly different from all the others. Ron said yes, he’d met most of the Soviet leaders (not true of course) and what separated Mikhail Sergayevich from the pack was that he wanted ‘to do what Lenin was teaching’ and extract the Bolshevik kernel from Stalin’s perversions. Lenin, the President explained, had favoured auguries of glasnost and perestroika and ‘had programs that he called the New Economics and things of that kind.’ Ron had evidently noted the rehabilitation of Bukharin and figured it was finally safe to come out for the NEP.”[15]

Cockburn and Vidal were each, in their different ways, totally unique in the North American journalistic landscape. They transformed the terrain of political commentary, and are all but impossible to replace. Where are the radical critics that can make you laugh while illuminating how Marxism really does explain the world around us? Where are the rebels in the ruling class (Lewis Lapham an exception) who can observe their own class with such dry disdain and sympathy? This is not merely a question of style, of form. The role of Cockburn and Vidal, and by extension, CounterPunch, in the years after September 11 was vital in developing a culture of opposition, of a pluralist approach that sometimes embraced (in my opinion) some questionable characters. It is as if one has to choose between solid analysis and good and informative writing. There are very good writers and muckrakers, but often with analysis that is less than perfect. There are others who are great analysts, but are not necessarily the most pleasurable of reads. Cockburn once wrote that his father, the great journalist Claud Cockburn, encouraged him to read Marx when he felt run down, and it was a habit he picked up. Myself, I pick up Cockburn and Vidal. •