One Year After the G20 Protests: Forms of Protest Reflect Our Power

In June 2010, leaders of the G20 countries gathering in Toronto were met with a large protest march organized by union officials as well as by a series of actions organized by community-based activists. Police arrests of activists began before the march. Many hundreds of arrests followed, in the wake of attacks on property in downtown Toronto by some protestors.

In this article, Clarice Kuhling looks at why some people who want radical change embrace attacks on property as a tactic and what this means for those who recognize that “smashing shit up” doesn’t help build the kind of power needed to resist the state’s austerity agenda and change society for the better. The article is adapted from a longer chapter in a book due out from Between the Lines in November 2011 entitled Whose Streets? The Toronto G20 and the Challenges of Summit Protest, edited by David Wachsmuth and Tom Malleson.

— Editors of New Socialist Webzine.

On the one year anniversary of the anti-G20 protests, where the largest mass arrests in Canadian history were carried out, civil society groups held a press conference challenging the lack of a full public inquiry into police abuses and breaches of civil and political rights – the details of which are still unfolding. And more than one year later, the crucial question as to why property damage repeatedly re-emerges as a protest tactic remains under-analyzed.

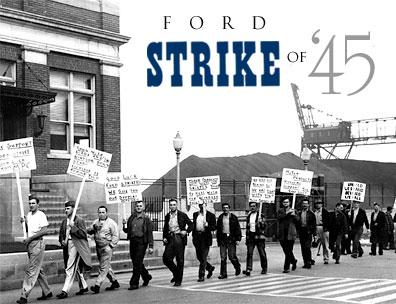

Factors in adequately understanding the context in which breaking windows has emerged as a seductive form of protest tactic include the absence of mass social protest, the weakening of left politics oriented in some way to mass action and mass struggle, the decline of working-class organizing both inside workplaces and in the community at large, the growth of an increasingly passive, unaccountable, and bureaucratic labour leadership and union structures which reinforce this passivity, and the decline of spaces and places to connect with working-class activism.

“Smashing shit up,” then, is both an expression of this context and a direct reflection of the low level of struggle and resistance in labour unions and on the left. Ultimately, selecting out particular protest tactics for criticism without a larger critique of strategies of left resistance inhibits our ability to learn the lessons that this round of protests and movement building could teach us about building for the next.

These tactics keep reappearing precisely because they represent a wholesale departure from the forms of passive politics and bureaucratically controlled resistance that have increasingly monopolized the political terrain of working-class struggle in the last half-century in both Canada and the USA.

Labour Retreat

As a crucial mechanism and expression of working-class power, labour unions would be one of the most obvious institutions from which a challenge could be mounted. However, the Cold War greatly weakened radicalism within working-class movements: many leftist radicals were purged from unions, and some unions, like the Canadian Seamen’s Union, were destroyed outright through these purges.

And while the legal protection won in the 1940s did grant workers the freedom to organize and bargain, with these new rights came restrictions. Workers could no longer legally engage in sympathy strikes, strike during the life of a collective agreement, or strike in support of political demands. Union officials were now obliged to police their own members by discouraging them from undertaking illegal strike action.

The new collective bargaining process thus imposed a host of regulations and requirements on workers which dramatically circumscribed their activities. The site of struggle shifted increasingly away from the streets and workplaces and over to the sterile boardrooms of bargaining tables – and into the hands of the union officials, bureaucrats, and professionals who increasingly dominated these spaces.

As David Camfield notes, the union officialdom which emerged as a distinct social layer became increasingly preoccupied with “preserving stable union institutions and bargaining relationships with employers.” Labour militancy was sacrificed in exchange for labour peace, and gradual incremental gains in the welfare state were won (for a time) at the expense of further struggle for more profound social transformation. And while radical movements did emerge in the 1960s and 1970s, they failed to build a new radical left inside the working-class movement of any significance, except in Quebec.

Previous historical periods also had more openings for people to connect with working-class politics and activism. These openings were crucial, and provided the organizational forms and the physical and intellectual spaces where people could plug into militant working-class struggles. These “infrastructures of dissent,” as Alan Sears calls them, are “the means of analysis, communication, organization and sustenance that nurture the capacity for collective action” and for challenging the system.

Such infrastructures of dissent included various Marxist and anarchist political formations, left-wing ethnic organizations, community and civil rights organizations, radical publications, and left oppositional currents within unions. But these also included actual physical spaces (the community halls, bars, sports clubs, and coffee houses) and the cultural and leisure activities that people shared (the choirs, plays, parades, picnics and dance groups) as well as the informal networks that existed in people’s neighbourhoods, communities, and workplaces. All of these provided the spaces and forms of organization necessary to debate and analyze, learn how to organize and fight, to dream and hope and offer visions of what kind of workplace or society should emerge.

The decline, co-optation or destruction of such vehicles for working-class resistance, occurring alongside the declawing of unions, has dramatically altered social life. Forms of collective action that were previously part of working-class experience both in workplaces and in communities have been replaced by individual coping strategies, and the openings once available to plug into militant working-class struggles have dramatically narrowed for young activists, not to mention for anyone who is disaffected, disenfranchised, and disillusioned.

Thus younger activists have very little connection to and identification with unions in particular and radical working-class politics in general. Instead we have a widening cleavage – first apparent during the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) protests in Quebec City in 2001 – between newly radicalizing younger activists with little exposure to radical working-class politics and labour activists who, as David McNally put it, “are not connecting with the energizing experiences of more militant forms of direct action and who have yet to make a connection with anti-capitalist ideas.”

The decline and retreat of working-class activism (which includes the structural separation of workers arising from the reorganization of work and individual coping strategies which have gradually replaced more collective forms of action) is an objective problem, a real historical development emerging from a historically specific social context. And the present day separation between labour movement activists and radicalizing youth – between workplace struggles and street protests – is a direct expression of this historical development and context.

However, bureaucratic labour leaderships, rather than serving as a force for social change, have increasingly acted to inhibit more militant formations within the unions, to stymie working-class resistance, or even to block union action of any kind. Sometimes union leadership control goes beyond simple orchestration of contained mobilizing efforts and, sadly, extends toward inhibiting the formation of more militant fight-back strategies which might provide alternative spaces for collective action. Then, as now, the top leadership of the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) was centrally involved in orchestrating (and policing) from above the form that labour protests were to take. Compare CLC President Ken Georgetti’s statement in April 2001 (“It’s a good symbolic act to walk away”), with a press release by him on the Saturday of the anti-G20 labour march: “We cooperated with police in choosing the route and had hundreds of parade marshals to maintain order.”

Rupturing Boundaries

The commonly heard chant “Whose streets? Our streets!” aptly captures the feeling of exhilaration at registering our dissent by taking over the streets in a demonstration – especially when done in ways that rupture the tightly choreographed boundaries of typical protests. The experience of being part of a mass crowd in opposition can be inspiring and can challenge previous assumptions about the world.

But this heady feeling doesn’t last long if opposition is not translated at some point into something more, some tangible result. The awe and inspiration we experience from being part of such events is quickly dulled when marching in circles or to empty parking lots is all we ever do, and when any attempts at more oppositional forms of protest and more militant actions are immediately shut down or managed from above, like a faucet turned on and off (mainly off!).

Dismissively tossing accusations of ‘adventurist’ at the tactics employed by some protesters in response to such manoeuvrings from above tends to obscure the ongoing reality of labour leadership’s simultaneous passivity and collusion in repeatedly shutting down militant struggle. It also fails to acknowledge the sheer anger that many feel at the failure of various community and labour organizations to adequately mount an effective fight-back strategy in the face of an ongoing onslaught by capital against the working-class.

This onslaught is not felt equally across generations or across the whole working-class, and it reflects the emergence of new and complex forms of working-class differentiation. It also presents new obstacles and challenges to building solidarity. The role of capital and the state in reorganizing the labour force and redistributing wealth to favour capital (controlled by some segments of older adults) at the expense of youth wage-labour can clearly be seen in the explosive growth of subordinate service occupations and temporary, part-time, contract work held by younger non-unionized workers (as well as workers of colour, and particularly women of colour) and in the setting of minimum wage standards (not to mention ‘flexible’ labour markets).

According to one report, two-thirds of minimum wage earners are under twenty-four years of age, and while minimum wage would have placed one approximately 40 per cent above the official poverty line in the mid-1970s, it now positions one 30 per cent below that line. Similarly, the unfortunate tendency of some unions to protect their own members at the expense of the larger working-class, or even to bargain differential protections for workers within the same collective agreement (seen in the increased incidence of two-tier contracts which guarantee benefits to older generations of workers but diminish or outright eliminate these provisions for newer, younger workers) has further complicated efforts at bridging the yawning gap between radicalizing youth and labour movement activists.

From Anger to Action

We need to have honest, open, respectful discussions that begin to grapple with the level of anger that the intensification of neoliberal capitalism has generated, and that begin to strategize about how we can begin to translate anger into a resistance movement actually capable of turning the tide – without self-righteous name calling or accusations. Unless we contend with the reality that some young activists will turn to particular forms of direct action as a substitute for any other kind of power, then we will continue to have militant breakaway marches and smashed windows. As long as a servile, passive politics takes the place of (indeed ‘substitutes’ for) active militant resistance, then we will continue to see part of the public expressing their frustration in ways that are not easily contained.

“As long as a servile, passive politics takes the place of (indeed ‘substitutes’ for) active militant resistance, then we will continue to see part of the public expressing their frustration in ways that are not easily contained. And yet, an analysis of strategies and tactics is desperately needed.”

And yet, an analysis of strategies and tactics is desperately needed. The unfortunate reality is that smashing a window, even many windows, does not challenge the power of capital in any fundamental way, let alone overthrow the power of capital. Profits are not impeded when insurance can cover the cost of replacing windows, and capitalism does not grind to a halt – or even turn tail and run – when specific meetings are shut down or interrupted or when the ‘symbols of capitalism’ (the windows of Starbucks and Adidas, for example) are smashed. Changing the world would be so much easier if this were the case!

Rather, the inequality inherent in capitalist production derives from the fact that the value of the work we perform is more than what we are paid in wages, and that difference (the profit) goes to the employer, not us. Disrupting this social relation means getting at the core of what makes capitalism function as an economic system. Because the profit taken from us relies on our continuing to work, effectively challenging capital would require disrupting this chain of profit acquisition through stopping work. And going from challenging capital to ultimately overthrowing capital would involve seizing control of, and paralyzing the production of profits in, these very workplaces.

This dauntingly far-reaching task of seizing control – collectively and democratically – of our workplaces and other institutions will thus obviously require large mobilizations. But it will also require large numbers of us actively working together, self-organizing – in stark contrast to more passive forms of political engagement (such as electoral politics) undertaken by isolated individuals. And this mass self-activity must be capable of disrupting the immobilization, powerlessness and cynicism that we often feel, so that we begin to experience our world in new ways – as makers of history capable of changing our world rather than bystanders watching our world make or break us. Tactics like an occupation, blockade, militant strike, or sit-in, for example, are some of the methods that better enable us to begin to take power with our own hands. These three elements – mobilizing a lot of people, in ways where we ourselves are active and not passive, and in ways that enable us to experience and wield our power collectively – are key ingredients in building our counter-power. •

This article first appeared on the New Socialist Webzine.