Libya and the Danger of Humanitarian Intervention

Events are rapidly unfolding in Libya and the surrounding region, and military intervention appears to be an increasing reality as the hours pass. One look at the principal Western nations deploying their military forces to the Mediterranean says a great deal: the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and France. Italy has also repudiated its friendship treaty with Libya, effectively freeing up Italy’s military outposts for use in southern Libya. These are the same Western powers that intervened in Haiti, Kosovo and Afghanistan on ‘humanitarian’ grounds, and they appear to be rearing their ugly heads again under the same humanitarian pretext.

Some context is necessary. States like Libya have the right to full sovereignty under the United Nations’ Charter, but individuals also have equal rights to “life, liberty and security of person” under the UN Declaration of Human Rights (ignoring here the structures of these institutions in terms of the powers they represent). From this contradiction between state sovereignty and human rights emerges the issue of ‘humanitarian intervention.’

Noam Chomsky notes that “the right of humanitarian intervention, if it exists, is premised on the ‘good faith’ of those intervening, and that assumption is based not on their rhetoric but on their record, in particular their record of adherence to the principles of international law, World Court decisions, and so on.”

One should certainly assess the dismal record of the U.S., Canada and their allies on this matter. The urgency of the Libyan crisis, however, and the mounting press chorus for intervention merits immediate attention. Suffice to say that the hegemonic American superpower has asserted its overwhelming military force with ruthless force wherever strategically possible. According to a key planning document of the Canadian Defence Forces, it is “in Canada’s interest to cooperate closely with the United States so long as national sovereignty is not sacrificed.” National sovereignty has always been somewhat of an afterthought in security and defence matters in the Canadian state. Sovereignty has proven consistently subservient to cooperation with U.S. imperial ambitions on almost all major foreign policy issues. Canada pursues its own imperialist ambitions in conjunction with the U.S., not apart from it.

Western Powers and the Conflict in Libya

With this in mind, the current status and pace of events unfolding in Libya are reason for grave concern in Canada. Western allies continue to engage in a level of rhetorical evasion, with U.S. Defence Secretary Robert Gates playing down the idea that U.S. forces would intervene militarily in Libya. But there is a problem here. Namely, his rhetoric stands in complete contradiction with facts on the ground.

U.S. forces have already been deployed to the region. The Kearsarge, an amphibious assault ship, and the Ponce, a transport docking ship, have been deployed to the Mediterranean. An additional 400 Marines are en-route “in support of the Kearsarge.” The aircraft carrier, USS Enterprise, is currently in the Red Sea and could deploy fighter jets in a Libyan no-fly zone, should Egypt allow the jets to pass through its airspace. It is impossible to assess precisely what U.S. resources are being dedicated to Libya, as facts are shrouded in a veil of national security.

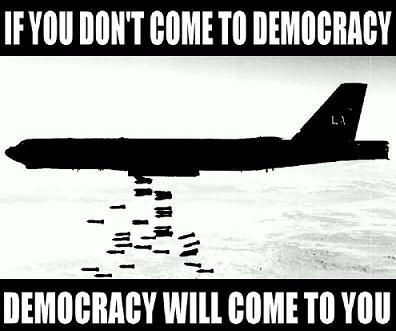

With respect to the no-fly zone, the United Kingdom is clearly prepared to enforce a zone without a resolution from the United Nations. “There have been occasions in the past when such a no-fly zone has had clear, legal, international justification even without a Security Council resolution,” UK Foreign Secretary William Hague said. One such ‘occasion’ occurred recently – in Iraq. Iraqis will be recovering for years from the brutal siege and occupation that left, in the most modest of estimates, over 100,000 dead. “Let’s just call a spade a spade,” Secretary Gates bluntly stated in outlining what a no-fly zone over Libya would entail. “A no-fly zone begins with an attack on Libya to destroy air defences. That’s the way you do a no-fly zone.” This is worth keeping in mind, as both the Liberals and New Democratic Party in Canada have openly supported implementing a no-fly zone over Libya. The Conservative Party has remained notably silent on this point.

Given that the UK is promoting a no-fly zone through NATO rather than the UN, it should come as no surprise that the United States is also prepared to intervene outside of a UN mandate. Secretary Gates made it very clear that there was “no unanimity within NATO for the use of armed force.” His language is carefully chosen. This entirely evades the legitimacy of NATO acting outside of a UN mandate. In fact, it sidesteps the UN altogether. This also evades the illegitimacy of threatening the use of force, which is explicitly prohibited within the UN Charter, on the premise that such actions and threats are unequally deployed against weaker states.

All of this points toward a NATO-led attack based on some premise of humanitarian intervention and benevolent intentions. The question of foreign intervention, however, is not entirely straightforward at this point. The National Libyan Council, which is asserting itself as the post-Gaddafi transition regime, appears divided on calling for foreign intervention. This ambiguity alone could easily form the pretext for outside intervention.

France has also begun sending aid to rebel and opposition forces in eastern Libya. MRZine editor Yoshie Furuhashi rightly notes that “ostensibly the content of the French aid is humanitarian, ‘doctors, nurses, medicines and medical equipment,’ but how long will it take before the need to send humanitarian aid becomes a pretext for sending soldiers to guarantee its safe delivery?”

The question is vital, but so is the rapidly escalating humanitarian crisis. Some 75,000 people have already fled Libya for neighbouring Tunisia, with an additional 40,000 waiting at the border and numbers growing by the minute. The UN High Commission for Refugees is calling for “a massive humanitarian evacuation of tens of thousands of Egyptians and other third country nationals” because “we are witnessing now a huge humanitarian disaster.” The danger is that a ‘humanitarian evacuation’ can easily slip into ‘humanitarian intervention,’ and everything seems to indicate that this is a distinct possibility.

The Canadian Response

The Foreign Minister of France, Alain Juppe, has explicitly rejected military intervention without a “clear mandate” from the UN Security Council. Canada has, indeed, a mixed track record on this point, often now willing to act outside of the UN when in the ‘national interest.’ Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Foreign Affairs Minister Lawrence Cannon have remained notably silent on the matter, leaving Canada with ample room to act outside of a UN mandate. Writer and activist Arundhati Roy rightly notes that “keeping quiet, saying nothing, becomes as political an act as speaking out. There’s no innocence. Either way, you’re accountable.”

“Canada pursues its own imperialist ambitions in conjunction with the U.S., not apart from it.”

To make up for its absence at the UN, Canada is instead bolstering its physical military presence in the region. The Canadian Forces have deployed the HMCS Charlottetown and its 240 personnel to the Mediterranean, and additional Canadian personnel are already located on the neighbouring island of Malta, where an operations centre has been established by the United Kingdom. Prime Minister Stephen Harper has also announced his intentions to exceed sanctions imposed by UN Security Council Resolution 1970, which calls for an arms embargo on Libya, cargo inspections of ships headed to Libya, and a travel ban on Gaddafi and individuals associated with him.

For all of this action, the Canadian national press are lauding the government in all of its liberal benevolence. “Canadians who believe that their military’s primary purpose should not be to fight wars, but fervently want their troops to only be Boy Scouts, should be pleased by Ottawa’s evolving commitment to the crisis in Libya,” writes PostMedia journalist, Matthew Fisher. Even with a comparatively small military presence relative to the ongoing Canadian mission in Haiti, “there will still be a feel-good factor.”

Humanitarian Imperialism

It is worth stressing that the threat of using force and violating state sovereignty outside of the UN Security Council runs explicitly against the UN Charter. Chomsky has previously quoted two (liberal) authorities on the matter, Hedley Bull and Louis Henkin, who offer vital context to the present circumstances in Libya. Bull some time ago warned that: “Particular states or groups of states that set themselves up as the authoritative judges of the world common good, in disregard of the views of others, are in fact a menace to international order, and thus to effective action in this field.” This certainly applies to NATO powers as they assert themselves outside of the UN as “authoritative judges of the world common good.”

Henkin, in a similar vein, has written that:

“pressures eroding the prohibition on the use of force are deplorable, and the arguments to legitimize the use of force in those circumstances are unpersuasive and dangerous… Violations of human rights are indeed all too common, and if it were permissible to remedy them by external use of force, there would be no law to forbid the use of force by almost any state against almost any other. Human rights, I believe, will have to be vindicated, and other injustices remedied, by other, peaceful means, not by opening the door to aggression and destroying the principle advance in international law, the outlawing of war and the prohibition of force.”

It appears that NATO powers are, once again, setting themselves up as “authoritative judges of the world common good,” as the U.S. and Britain – coupled with disgraceful silence from Canada – are clearly willing to implement policies independently from the UN. There are clear “pressures eroding the prohibition on the use of force,” however well-couched they may be in humanitarian rhetoric. The historical record of American and Canadian ‘humanitarian intervention’ provides ample grounds for rejecting any form of involvement. Even the use of military forces for ‘humanitarian evacuation’ is a danger that needs close watching, as this could quickly slip into outright intervention and sustained military presence. In the midst of all of this, quickly obscuring from the picture are the Libyan people, who began this popular movement in the name of democracy and freedom, established on their own terms. •

Matthew Brett is a graduate student in political science at Concordia University. He can be reached at brett.matthew@yahoo.ca.

Also available as a PDF in French – translation by Marc Bonhomme.