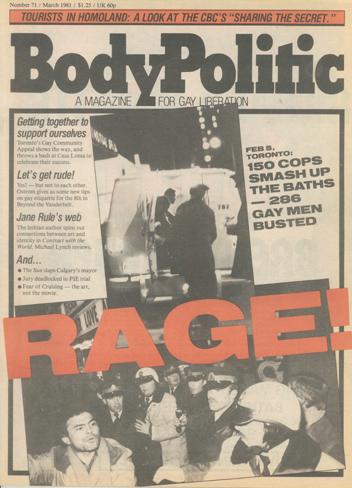

30 Years On: The Toronto Bathhouse Raids and Sexual and Gender Liberation

On February 5, 1981 150 Toronto cops busted into four gay bathhouses and arrested 306 people on charges of being found-ins or keepers of common bawdyhouses. These arrests were deliberately conducted so as to humiliate and terrify the men who were charged. Doors were kicked in and men were dragged out naked, verbally abused and beaten up. In 1981, there were no human rights protections from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, and people could be and were fired simply because they were perceived as lesbian or gay. Many were fearful of employers, families or friends finding out that they had sex with people of the same gender. There were almost no major public figures who were out and no lesbian/gay visibility in the media or the entertainment industry, except as threats or objects of derision.

But these raids did not achieve their goal of turning back the clock on Toronto’s lesbian and gay communities, which were beginning to consolidate themselves politically and geographically. Instead, they ignited a mighty and militant movement that ended up changing the rules of sexual politics forever, ultimately winning full legal equality if not liberation.

Looking Back at Anger

The days that followed the bathhouse raids saw mass militancy fuelled by an electric rage. I have been on a lot of demonstrations before and after, but the ones that followed the raids stand out for the fury and joy of the participants. The demonstrations combined civil disobedience with mass mobilization, with thousands chanting “No More Shit” and “Fuck Your 52” (the raids were conducted by Toronto Police’s 52 Division). Busy streets were shut down by angry crowds who were defiant and totally unwilling to follow the rules.

The movement was not born out of the raids. The Stonewall riots in New York in June 1969, a time when many people were becoming radical, had kicked off a new phase in gay liberation and lesbian feminist organizing. In Toronto, relatively small numbers of people began organizing in new ways, developing media (the magazine Body Politic), community spaces and political organizations. After the bathhouse raids, a much wider layer of the community mobilized, building on the foundations of the work done through the 1970s in developing political strategies and new ways of thinking about gender and sexuality.

The movement that emerged in response to the bathhouse raids, coalescing around the Right to Privacy Committee, was remarkable in its political sophistication. It developed a full spectrum of responses, ranging from militant civil disobedience in mass demonstrations to huge public meetings and effective legal defense for the hundreds facing charges. The outreach, for example leafleting in bars, was impressive and made it the responsibility of anyone who was gay or lesbian or supportive of sex and gender freedom to do something.

Ultimately, this movement made an important contribution to the politicization of lesbian and gay identities. Coming out, publicly announcing your sexuality, was not only a personal act of self-definition but also a political act of aligning with an activist movement. It was only as this movement began to win significant rights that the separation of sexuality as a lifestyle choice from sex/gender liberation as a political movement was possible.

The mobilization sparked by the bathhouse raids changed the way many thought about their own sexualities. Despite the hard work in the 1970s of the early gay liberationists, wide layers of people still felt tremendous shame and fear around their own same-sex activities in 1981. For those who were at those marches and meetings, something new emerged – pride, anger, a vibrant sense of comradeship and a transformative impulse to fight for justice.

Thirty Years On

Personally, I can say that there is no way I would have imagined that within my lifetime we would see full legal equality for lesbians and gays in Canada, a large number of out public figures (though not in certain realms, like sports), open discussion in the media and a wide range of movies, books and popular television programs with lesbian and gay characters. You may or may not like Glee, but it is a remarkable political accomplishment that it even exists. It is now actually regarded as bad form to express overtly discriminatory ideas about lesbians and gays, while 30 years ago it was commonplace. The experience of mobilizing against the bathhouse raids also provided a crucial political toolchest for AIDS activism and a militant, effective response to the impact of a devastating epidemic that was met with official inaction and even more a vicious clampdown on the part of the state.

It’s not liberation, but it is very real social change won through militancy. Yet it is important to understand the limits of these changes. The movement that grew out of the bathhouse raids won those reforms that fit most easily with a changing capitalist system as neoliberalism developed. One key aspect of the neoliberal agenda was to cut back the state, from slashing social programs to deregulating various industries. This included a partial moral deregulation that saw governments relax their controls over gambling, drinking, dancing and censorship of movies, books and plays. The goal was to open up new profit opportunities in these areas. The deregulation of sexuality aligned with this agenda, though it would not have happened without militant mobilization.

It is in fact common that our movements ultimately win those changes most compatible with the changing capitalist system, this side of the revolution. This does not diminish the gains, but it means that our victories are often contradictory, winning real reforms yet bearing the stamp of a system grounded in inequality and dehumanization. In the area of gender and sexuality, there is still a long way to go for real freedom.

Violence continues against people perceived as “queer,” that is as non-conformists in gender and/or sexuality. People still get beaten up and threatened, or even killed. The fear of violence remains part of the calculus of queerness in this society. High school is one place where this violence is particularly overt. It is disproportionately young men who carry out this brutalization, so full liberation means challenging the particular kinds of masculinity that promote violence against both women and those perceived as “queers.”

Only some sections of those who engage in same-gender sexual practices and/or gender transgression have won rights since 1981. There are very specific reasons that words “gay and lesbian” conjure up images of white men (and some white women) who are economically relatively well off. The whole way the movement has defined sexual freedom reflects the specific experiences of particular people in the global North and certain members of the elite in the global South.

Same-gender practices and gender transgression take many forms in a variety of cultural and geographic contexts, often among people who also engage in heterosexual practices and do not identify as “gay” or “lesbian.” Yet the model of sexual freedom that has taken shape over the past 30 years has tended to cast all other forms of same-gender sexuality as inferior relative to specific “out” lesbian and gay identities that have emerged mainly among white folks in the global North. It is a central feature of whiteness that the experiences of racialized people get read as inferior and “primitive.” This has been true in the area of sex and gender politics.

Indeed, some lesbian and gay figures, particularly in Europe, are fully aligned with racist and imperialist efforts that scapegoat people of West Asian, North African and South Asian backgrounds, claiming that the real threat to sexual freedom comes from “immigrants.” This makes overt what was already present beneath the surface in contemporary ideas about lesbian and gay rights as the pinnacle of sexual freedom.

Full liberation means challenging developing sex and gender politics that are anti-racist, anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist. They must also be anti-capitalist, as our ability to control our bodies and our lives is highly constrained by the way capitalism works. At a simple level, poverty undercuts sexual freedom, as people who are hungry, inadequately sheltered and stripped of rights often lack the power and resources to take control over their bodies and lives. Our sex and gender freedom is eroded by overwork and exhaustion, employer regulation of workers’ comportment and partner separation due to migration for work and survival.

It goes further. In capitalist conditions, lesbian and gay identities are largely forged through specific patterns of consumption, for example wearing certain clothes, sporting specific haircuts or going to particular commercial spaces such as bars. Capitalist social relations that turn goods and services into commodities for sale on the market ultimately have a huge impact on the way we live our genders and sexualities.

The movement that grew out of the bathhouse raids produced really significant gains that have made a real difference in the lives of many. We have to celebrate these gains, and learn from the mobilizations that produced them. We also need to work together to fight for a broader vision of sexual and gender liberation. •

This article first appeared on New Socialist Webzine.