Opening Ontario and Constraining Collective Bargaining

The Case of Carleton’s Capitalist University

As austerity measures intensify around the world, the axe has come down particularly hard on post-secondary education.[1] So-called education ‘reform’ has shown itself to be a lightning rod for confrontation. Throughout the U.K., in cities like London, Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, Cambridge, Belfast and Glasgow, student protests and university occupations have erupted over draconian cuts to benefit programs and the trebling of tuition fees. Over 130,000 protestors, joined by student, trade union and community activists, have taken to the streets to demonstrate against £1-billion in cuts to education, including wage restraint measures, new user-fees, furloughs and a host of public sector spending restraint measures. Despite the otherwise peaceful protests, the state and its police force have responded in the most aggressive of ways: mass arrests, kettling, preemptive overnight raids, tear gas and excessive use of their batons. Britain’s most senior police officer has recently warned: “The game has changed” and “disorder” will be dealt with accordingly.[2]

In order to deal with unprecedented budget shortfalls, caused, it must be recalled, by the lead agents of the capitalist class (its bankers, insurance companies and politicians), the public sector is now being strangled. The capitalist sector is, morerover, catching a second wind, and engaging further flagrant excesses. In the 12-months ending in June, the top 100 Financial Times-London Stock Exchange directors in the UK saw their earnings rise sharply by 55 per cent with the biggest increases coming in “performance-related” bonuses. They now earn two-hundred times more than the average UK worker.[3] As in the UK, much the same is taking place throughout the rest of Europe, with anti-austerity protests of students and workers erupting in Italy, Greece, Portugal, Spain, Belgium and elsewhere. Incredibly, rather than laying blame on the origins of the present (private sector-led) recession, budget shortfalls are being blamed on an allegedly bloated and outdated public sphere.

This is creating new openings for privatization of public assets and services as a means to pay for the crisis. In North America, the austerity measures are unevenly being introduced, though emphatically similar in their aims and measures. In Canada, the Federal Conservatives have responded with pay freezes, service cuts, corporate tax reductions, proposed asset sell-offs and the curtailment of social program spending.[4] In Ontario, much the same is occurring. This raises several questions. Where are the anti-austerity protests and the Canadian student movement? How are the federal and provincial budgets impacting public sector collective bargaining? And how are unions responding? In what follows, we address these questions with a particular focus on the recent round of bargaining between Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) Local 4600 and Carleton University in Ottawa.

Opening Ontario

As the Great Recession intensified throughout the summer of 2007, the Ontario Liberal government of Dalton McGuinty has responded, like elsewhere, not by rejecting neoliberalism, but by reinventing it. With an expected budget shortfall of $18.7-billion for 2010-11, and deficits expected to continue well into 2017-18, a number of measures were proposed in the spring budget to re-establish balanced-budgets. Despite some modest ‘pump-priming’ and avoidance of the massive cuts being inflicted in many countries in Europe and state and local government in the U.S., Ontario has adopted policies of tax shifting that reduces corporate taxation for competitiveness and increases taxes on workers, new user fees, wage repression, erosion of social assistance and the streamlining of public sector services. With the transition from ‘rescue strategies’ to ‘exit strategies,’ Ontario provides a vivid portrait of the re-invention of neoliberal policies even by centrist governments attempting to avoid a hard right fiscal turn. The budgetary measures were prefaced by the Speech from the Throne of 8 March 2010, titled the Open Ontario Plan. Together, the Throne Speech and the budget outline of the government’s plans and, recalling the 1990s and the Conservative government of Mike Harris, signal a new era of neoliberal austerity.

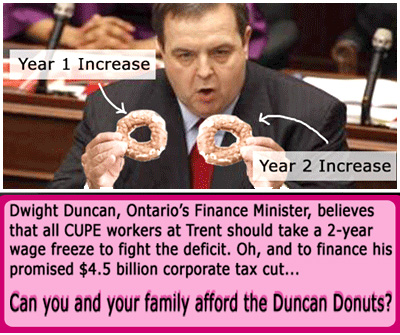

The Open Ontario Plan emphasizes three central policies. The first is ‘tax relief.’ The government of Ontario lowered the general Corporate Income Tax (CIT) rate from 14 per cent to 12 per cent; it will be reduced further to 10 per cent by 2013-14. This includes reductions in the CIT for manufacturing and processing, the reduction of the Corporate Minimum Tax, and the elimination of the Capital Tax. As well, personal income tax cuts have also been enacted, due in part to counteract the imposition of the HST. Further, in another example of the pursuit of market fundamentalism, nearly $1-billion will be lost by the government owing to cost overruns at public-private-partnerships and the introduction of privatization measures. All in all, following the full phase-in of Ontario’s comprehensive tax reforms, the marginal effective tax rate, which measures the tax burden on new business investment, will be cut in half by 2018. As such, businesses will be subsidized by $4.6-billion from tax cuts on income and capital over the next three years under the guise of stimulating “competitiveness” and attracting investment (expected to occur through private sector hiring, and ‘trickle-down’ economic theory).[5]

It must be recalled that Canadian post-secondary education has been in dire straits ever since reductions to the Canada Health and Social Transfer changes enacted by the Conservative government of Brian Mulroney and continuing through subsequent Liberal governments to the present Conservative government of Stephen Harper. Between 1987-2007, the percentage of university operating budgets funded by the federal and provincial governments declined from 81 per cent to 57 per cent. While in 1990 tuition fees accounted for 20 per cent of institutional operating budgets, today it’s over 50 per cent. Thus between 1991-2008 average domestic tuition fees across Canada increased by 176 per cent.

Ontario occupies the position as the most expensive province in the country to complete an undergraduate degree at on average just under $6000 per year, while in 1990 the average cost of Canadian tuition was under $1,500. Ontario is also the most expensive province to complete a graduate degree at on average $8,500 per year. This pales in comparison with Quebec’s average undergraduate cost of $2,415, which have been frozen for thirty-five years. It must be recalled that Quebec never passed the cost of federal funding cuts onto students and that college also remains free for residents. Similarly, between 2002-04, the government of Newfoundland and Labrador reduced tuition fees by 25 per cent and have since then been frozen (although austerity measures may undermine the freeze, and the Quebec differential). In Ontario, the tuition fee freeze that students won between 2004-06 was cancelled by the Liberal government and replaced with a tuition framework that allows for increases of between 5 and 8 per cent per year until 2012. As a result, Ontario undergraduate students hold the largest debt at graduation at on average $37,000 per student, and increasing to $43,700 for PhD graduates. At $9,718 average per-student funding, Ontario spends 20 per cent less than the national average of $12,500 leading to larger class sizes and debt overhangs that have resulted in the number of summer days a student would have to work to make enough money to pay tuition fees for one year rising from barely over six weeks in 1980 to fifteen weeks by 2010 (based on undergraduate fees averaging $5,951, minimum wage and an eight hour work day). As well, Ontario provides no funding transfers to universities for foreign students.

Both Premier McGuinty and Finance Minister Duncan have consistently reiterated that they are not ruling anything out when it comes to legislating further austerity measures, wage freezes or employee furloughs. Such measures will allegedly ‘save’ the government $750-million over two years. Bearing in mind the public sector attacks at the federal and provincial spheres, McGuinty has urged Ontario municipalities to follow their lead and impose a 5 per cent target of austerity while freezing wages. Borrowing from the austerity discourses that have been proffered by NDP, Liberal and Conservative governments alike, McGuinty and Duncan have argued that the public sector has been ‘sheltered’ from the recession and should therefore ‘tighten their belts’ by sacrificing wages, benefits and working conditions. McGuinty has also warned that he could have ‘imposed’ this on municipalities (perhaps alluding to future plans?). In craftily suggesting that Ontario’s 139,000 municipal workers make a ‘sacrifice,’ opportunistic mayors and city councils throughout Ontario have turned to austerity and cuts (most blatantly visible in newly elected Toronto Mayor Rob Ford’s ‘gravy train’ mantra).

Not only does compensation restraint not extend to the private sector, it excludes those most generously remunerated by public tax dollars. The restraint measures exclude public sector managers and CEOs who are still entitled to ‘performance-related’ pay and bonuses. This means, for instance, that CEOs in organizations in the public sector are not included, such as University Health Network CEO Robert Bell (just under $831,000 per year) and OMERS CEO Michael Nobrega (at about $1.9-million per annum); and neither are corporations heavily dependent upon public sector contracts, such as P3s, or for profit companies like Extendicare and its CEO Tim Lukenda (at $1.5-million in yearly total compensation). The restraint act only targets workers, especially women, earning between fifty and twenty-five times less. Moreover, it needs stressing, that average public sector wages did not return to their real 1992 levels until 2008. The Ontario restraint agenda reduces public sector wages and begins to move them back toward their pre-1990s levels.

Third, the Ontario government is contemplating the massive privatization of public goods and assets in order to pay down its deficit. McGuinty’s Liberals recently paid $200,000 to CIBC World Markets and Goldman Sachs to write a ‘white paper’ proposing the creation of ‘SuperCorp.’ The idea behind the mega-corporation would be to combine Ontario’s Crown assets, including nuclear power plants, power generation and 29,000 kilometers of electrical transmission and distribution lines, its six-hundred plus liquor stores and gaming operations, in order to package and sell it off bit by bit. Paralleling these developments are also measures that aim to restructure employment standards legislation along B.C.’s ‘self-help’ model and the deepening of inter-provincial free trade agreements, such as that between Ontario-Quebec, which opens up procurement contracts, services and assets, including a NAFTA-like state-dispute resolve mechanism that could result in companies taking the provinces to court over ‘unfair’ treatment.

Collective Bargaining at Carleton

With the provincial government taking a firm stand on public sector wage restraint, the onus falls on public sector workers to protect the services they provide and use, and to achieve fair compensation packages for the work they do. In the Ontario university sector alone, some 25 locals of CUPE representing both academic and non-academic staff had collective agreements expire between March 31st and August 31st 2010. Through CUPE Ontario, bargaining units in the university sector were invited to sign on to the resolution developed by the Ontario University Workers Coordinating Committee (OUWCC). The resolution advocated that “Locals at the bargaining table in 2010 and 2011 commit to no concession bargaining and the core coordinated bargaining proposals.” These included discussing the appropriateness of flat rate wage increases, and enhancing efforts at improving benefit and pension plans, employment equity and job security as well as collective agreement language on eliminating violence in the workplace.

Of the seven proposals contained in the OUWCC resolution, two are of particular importance. The first was committing to negotiating new wage and compensation packages in spite of the provincial government’s desire to impose wage restraints. The second was encouraging Locals to sign three-year collective agreements. The goal in the former was to ensure that public sector workers are not the ones who must pay for bailing out the corporations and banks. In the case of the latter, encouraging locals to sign on to three-year agreements was one method of ensuring that coordinated bargaining could continue and that university locals could more effectively support and contribute to the struggles in other cities. The value and utility of coordination across the university sector raises several important strategic and political questions that, in and of itself, requires further unpacking and future discussion.

In addition to coordinated bargaining at the provincial level, two Carleton University CUPE Locals (2424 representing support and administrative staff and 4600 Unit 1 representing teaching assistants (TA) and Unit 2 representing contract instructors) as well as the faculty association (Carleton University Academic Staff Association-CUASA) had collective agreements expire between April 31st and August 31st 2010. A third CUPE Local’s (910 representing physical plant workers) agreement will expire at the end of December. All in all, then, Carleton’s ‘Big Four’ unions were essentially bargaining at the same time. This created the ideal circumstances – at least on the surface – for coordinated pressure. As one way to develop and enhance the cooperation of the different bargaining units, the four union locals joined with both the undergraduate (CUSA) and graduate (GSA) student associations in a loose association called ‘Campus United.’ Together, various participants attempted to develop a pro-active support system through which activities and resolutions could be coordinated, but also a space in which bargaining strategies, tactics, messaging and due process could be openly discussed, debated and built upon. Weekly inter-union meetings allowed representatives to keep their own memberships informed and afforded the opportunity to see what issues could be harnessed together for purposes of collective bargaining. But there is a big difference between bargaining together and bargaining collectively.[7]

Differences Between Workers

Despite what were very productive and helpful meetings over the summer and into the fall term, several key issues emerged. The most immediate was the differences between workers who held positions as ‘careers’ and those that held positions as ‘jobs’ as a source of temporary ‘funding’ to get through graduate school or as workers in part-time teaching positions. On the one hand, the faculty and the support staff with careers and a long-term investment in the Carleton community and, on the other, the contract instructors and teaching assistants that were either precariously employed with little job protections and/or graduate students with a set deadline for the completion of employment as stipulated in their offer of admission.

Further, it became apparent that the unions each faced their own internal issues that affected the extent to which a coordinated strategy could be developed and implemented, such as the legality of solidarity strikes and issues related to potentially crossing picket lines. For CUASA, there existed the traditional core of ‘business unionists’ who were much less concerned about labour solidarity than about what they deemed to be their own principal issues (as there was to some extent in 4600). It would be difficult to find a union today without some central concern with its own self-preservation. However the situation presented itself as an historic opportunity for Carleton’s Big Four unions to demonstrate not only their cumulative strength in numbers, but to engage in the sort of social movement unionism premised upon the building of collective capacities, mutual reinforcement and cross-campus labour solidarity. While there was certainly strong coordination between 2424 and 4600, including joint events, a joint information picket and several instances of cost-sharing, a real opportunity was floundered largely resulting from the processual issues in filing no-board reports[8] that placed CUASA, CUPE 2424 and CUPE 4600 in legal strike positions on three different days (November 15th, 17th and 22nd respectively). The result, as collective bargaining went on, first, CUASA, and later CUPE Local 2424 reached tentative agreements, leaving Local 4600 isolated without their most valuable allies.[9]

The other noticeable issue affecting coordination between the different union locals was historical. In 2007, CUPE Local 2424 had gone on strike for 18 days. With the lingering anxieties at the possibility of another strike and the difficulties of watching the other unions cross their picket lines (despite some members coming out to engage in solidarity picket duty), no one was eagerly anticipating a strike. Yet, CUPE 2424 still received an 83 per cent strike mandate from its membership and it was clear that, if deemed necessary, job action would have taken again.

CUPE 4600 also faced a number of internal challenges. The largest and most apparent was learning from the mistakes made during the last round of bargaining (2008-09) in which the members voted ‘no’ to a strike mandate, which resulted in the subsequent loss of fixed tuition indexation.[10] This was against the backdrop of York University’s widely publicized 2008-09 strike action that ended in debacle for both the university and the union, and public resentment over striking OC Transpo workers in Ottawa. This created an environment that was less than conducive to strike action, let alone unions.

An additional challenge was mobilizing the membership, including the influx of several hundred new members. In this regard, several different strategies were employed. An active role in ‘welcome-back’ week events put on by the GSA at the beginning of the academic year that ensured face-to-face interaction with new members and to create an atmosphere where members felt the executive was always approachable. As well, the local hosted a ‘meet your union’ night that offered members the opportunity to socialize in a relaxed environment. There was also an effort to ensure at least one union executive member was present at each departmental TA orientation session to inform new members about their rights and responsibilities under the collective agreement, as well as to encourage them to be involved in their union.

In addition to mobilizing new members, it was equally important to ensure that wider communication and outreach strategy reflected key concerns at the bargaining table in such a way that would appeal not only to the membership but also to the wider community. Given that there were numerous issues for both bargaining units on the table, the bargaining teams selected three or four major issues to concentrate on and emphasized what were the most troubling aspects in the most reasonable ways possible. This proved to be a very effective strategy. By holding information tables several times on campus, participating in open-panel discussions[11] and engaging in brief student radio Q&A periods, this led many to declare that 4600 had won the public relations campaign.

Having run a strong mobilization and communication campaign, members of the respective bargaining teams focused on moving talks along with the employer at the bargaining table. This was by far the most difficult and frustrating aspect of this round of bargaining. It was apparent from the start that the university had little interest in seriously dealing with the union. This was in large part because of the negotiations with the faculty association, and an administrative attitude of arrogance with regards to 2424 that had one of the University’s bargaining officers declare that a ‘monkey could do their job.’ This relative unimportance was evident in that requests to begin bargaining in August were repeatedly met with the response that the employer didn’t have a bargaining team together, that it was summer time and people were away on vacation. This disinterest in beginning the bargaining process led to filing for conciliation in mid-August to force the employer to sit down at the table.

Three dates for meetings were set for both units of 2424. The first meeting for Unit 1 TAs was held on September 8th to exchange proposals. The meeting scheduled for three hours was cut two hours short by the employer because they were unprepared to respond or pose questions about the union’s proposals. The next session for Unit 1 was the first official conciliation meeting held on the 24th of September. In relation to this, it took the first conciliation meeting on the 23rd of September for the employer to exchange proposals for Unit 2! It is quite unfortunate that a difficult bargaining climate had to be made more difficult by unreasonable delays in simply beginning the negotiation process. However, by the start of October, bargaining meetings were held on a nearly weekly basis and while not every session was positive or necessarily productive, it should be noted that the atmosphere at the table was civil.

However, as CUPE 4600 moved closer to a legal strike position, the university administration demonstrated their true colours in regards to unionized labour. Under the guise of ‘fulfilling their obligations to students’ as well as ‘protecting the welfare of students’[12] the university’s “Contingency Plan” sent to all Deans and Associate Deans from Assistant Vice-President Academic Brain Mortimer on November 14th, stated that, “it is essential that the university have available all of the information that it requires to complete its mission even if some employees are on strike.” Meaning that, “all documents, files, computer records, e-mail and voicemail that are part of the university’s work must be accessible by appropriate supervisors and managers.”[13] Further, the Contingency Plan requested that all departmental chairs and directors collect from TAs and Contract Instructors, “(i) all ungraded work (ii) all graded but unreturned work and (iii) all interim term grades…well before the first legal strike date.” Quite clearly, the Contingency Plan sought to create the conditions for members of 4600 to scab on themselves by handing over the products of labour that would be withdrawn during a strike. Further, this Plan demonstrated just how little value the university places on the work performed by TAs and Contract Instructors by effectively stating that the work could be done without us if we were foolish enough to let them do it. In short, what the Contingency Plan at Carleton indicates is the willingness of senior university administration to undermine the bargaining position and power of unions by any means at their disposal.

Surveying the Outcome

The first obstacle in resisting the public sector wage freeze at Carleton was to convince members that such a move by the employer constituted a serious threat to working conditions and take-home pay. It was argued throughout the fall that this could not be accepted. Across Canada between 2003-09, rent, inflation, food and public transportation increased between 7 and 20 per cent, while tuition rose on average over 26 per cent. These conditions are all generally worse in Ottawa. As such, convincing the membership to grant a strike mandate proved rather straightforward. The challenge was to bargain from a position of strength, using support from the Carleton community and our members’ strong strike vote mandates on October 29th of 74 per cent and 89 per cent for Units 1 and 2 respectively.[14]

When the topic of wage increases was broached during the initial bargaining sessions, the employer responded that their hands were tied (by the province and the Board of Governors) and that they couldn’t move from the province’s direction of zero per cent over two years. This was unacceptable, especially since it was revealed that tuition rates would be rising 4.5 per cent each year between 2011-17, seriously eroding the post-tuition income position of graduate students. The union pressed the university’s bargaining team to return to the Board of Governors and obtain a new mandate.[15] Despite the evidence and data presented that demonstrated increasing university revenues (a large part from increased enrollment and tuition costs), the university did not change their tune of austerity.

It was not until the strike deadline was approaching that movement began from the employer on wages. At first it was ‘hypothetical,’ then a proposed low ball ‘signing bonus’ offer. It was only when there was less than a week before the strike deadline that the employer began tabling wage increases. The increases to the base wage in part resulted from the tentative settlement reached with CUPE 2424, which saw increases of 1.5 per cent over the first two years and 2 per cent in the third and fourth. Similarly, the final offer tabled by the employer on November 20th (just two days before the legal strike deadline) included a 1.5 per cent wage increase for the first two years and a 2 per cent increase in the third year for Unit 1. It was the same for Unit 2 with an additional 0.4 per cent market sector adjustment in the third year. The inclusion of a market sector adjustment for contract instructors resulted from the growing wage disparity between Carleton and the University of Ottawa, which translated into roughly a 14 per cent difference per course taught!

Despite the climate of austerity, the CUPE 4600 settlements suggests some positive signs for university sector bargaining units in Ontario. First, successfully reaching new collective agreements at Carleton that included base wage increases should aid other university locals in negotiating similar agreements. Second, it demonstrated that provincial austerity measures and wage restraints constitute an unreasonable demand on the public sector. It does not take an arbitration ruling to prove this fact.[16] Third, the fightback against austerity can result in a much more engaged membership, with new people volunteering for union positions. It also resulted in numerous other people that may have in the past remained indifferent to the bargaining process to attend meetings, ask questions and become more engaged.[17] The task now, is to maintain and go beyond this mobilization by continuing to improve the working and the learning conditions for members of the Carleton community.

Moving Forward

It is clear that university unions confront increasingly neoliberal universities. Like other Canadian universities, Carleton has been steadily emulating the American model of privatized post-secondary education. The user-fee model, which assumes private, post-graduation returns by charging up-front fees borrowed against expected future earnings, has shown itself to be a fundamentally flawed model for post-secondary education. What is needed is a comprehensive publicly funded post-secondary education system financed through progressive taxation measures to re-establish equitable access to university education and a measure of insulation from the vulgarization of research and study by corporate interests.

The Canadian Federation of Students’ Our Bright Future policy series papers offer a number of important and forward-thinking proposals. In order to cope with chronic under funding, many universities and colleges are turning to part-time instructors rather than full-time, tenured faculty, resulting in an increased rate of precarious employment as well as reduced student-professor face time. Democratic control over resources, knowledge production and public spaces is monopolized by private interests with no other aim but to make a profit.

A prominent example of this at Carleton is the attempted introduction of NAVITAS, a for-profit multinational educational corporation that charges (primarily international) students exorbitant fees while setting up shop at publicly funded institutions by renting space, using the university name and logo in promotional materials, hiring non-unionized staff, appropriating intellectual property and offering an unaccountable commodity disguised as university education.[18] Such agreements are part of Carleton’s strategy of marketizing education with a focus on corporate branding campaigns premised on business-related programs. This is also reflected in initiatives aimed at attracting foreign students who pay two to three times what domestic students pay in tuition fees. The VP of Finance at Carleton University, Duncan Watt, recently declared: “If we could find a way of actually attracting graduate students and paying them less money, that would be a very good thing for us.” As it is, tuition is projected to rise by another 31.5 per cent over the next six years.

Carleton University is just one example of how Canada’s post-secondary education is being slowly privatized. The corporatization of universities is being given further impetus by the turn to public sector austerity to bail out the banking system, after the biggest economic disaster in history. Students around the world are now also on the front-line of victims of the financial crisis. Activists engaged in student, trade union and community organizing are going to need to stand up together to defend public services. The neoliberal axe of austerity will only continue to cut deeper and harder if it is not met with resistance. •

Endnotes:

1.

Carleton’s marketing motto is “Canada’s Capital University.”

2.

See the presentations by George Rigakos, Mark Neocleous and Gaeton Heroux: “Neoliberalism In Transition: Security, Police and Capital.”

3.

Unfortunately the growing disparity between wealth and power is also occurring in Canada. See the recent study by Armine Yalnizyan.

4.

See the articles by Bryan Evans and Greg Albo and Carlo Fanelli and Chris Hurl at www.alternateroutes.ca.

5.

See Ontario’s Tax Plan Backgrounder, 2010; OPSEU: Ontario Cost Overruns; Ontario’s Long-Term Report on the Economy.

6.

Of positive note, a recent arbitration decision awarded 17,000 workers in long-term care homes a 2 per cent wage increase for 2010. In the ruling, the arbitrator said that employers and labour leaders must respond to economic decisions, not a government’s fiscal policy, in setting wages.

7.

This transfer of information to members is often taken for granted by large organizations but at Carleton it is a precious resource. For CUPE 4600, the contracts with contact information of members will trickle in for the course of months making the updating of a database a constant process. For the undergraduate and graduate student associations, the university does not provide a member list or contact information. Meaning that the only way either student association can contact members directly is by members individually signing up for a listserve.

8.

Either bargaining unit can request a no-board report during the conciliation process with the representative of the Ministry of Labour. Once requested and granted, a no-board report places the bargaining units in a legal strike or lockout position within 17 days of its receipt if a new collective agreement is not reached.

9.

This is reminiscent of CUPE Local 79 executives during the 2009 City of Toronto civic workers strike. They reached a tentative agreement and were ready to leave CUPE Local 416 on the lines alone, before mass rank and file uproar made them change their position. See Barnett and Fanelli, 2010.

10.

Fixed tuition indexation protected Teaching Assistants from increases in tuition by fixing it to a particular year regardless of when the TA began their employment. With the lost strike vote, there is now a system of rolling tuition indexation wherein tuition is fixed to the first year of employment.

11.

“Unions Speak to Students About Possible Strike,” The Charlatan.

12.

This is taken from an email entitled “Employee Rights and Responsibilities in the Event of a Strike” sent by the Vice-President Finance and Administration Duncan Watt on November 18th to all members of CUPE 4600 just four days prior to the legal strike deadline.

13.

The fact that emails and documents must be accessible by appropriate supervisors and managers should be a strong warning to other union locals in the university sector against using the university email service or saving grades on shared drives housed by the university server.

14.

“CUPE 4600 Strike Vote Results.”

15.

One of the most difficult aspects of bargaining in the university sector is the fact that the people who sit across the table are not necessarily the ones who make key decisions, especially regarding compensation packages. The bargaining mandate is developed by a special executive council from the Board of Governors, which leaves the representatives for the university as pawns for their ‘principals’ instead of actual bargaining agents.

16.

A recent arbitration ruling awarded the University of Toronto faculty association a 4.5 per cent wage increase over two years.

17.

While negotiations were ongoing with the unions on the Carleton campus, the university was also withholding the student fees that it collects and holds in trust for both CUSA and the GSA. This not only angered many people on campus, but demonstrated the inability of the Carleton senior administration to work with key campus communities. The student associations filed legal action against the university. See: www.gsacarleton.ca.