Two Takes on the Bolivian Uprising in Potosi

The Andean countries in Latin America have been at the centre of attempts to form anti-neoliberal political alliances and put on the agenda a 21st century socialism. Bolivia has formed an important crucible for these struggles. The battles of miners in the 1980s, the coca farmers from the 1990s on, the water wars in Cochabamba from 2000, the struggles of the indigenous communities for sovereignty and control over resources, across decades, and the confrontations with the ruling classes in Santa Cruz, have all inspired the Left outside Bolivia. The Movement for Socialism-Political Instrument for

the Sovereignty of the Peoples (Movimiento al Socialismo), or MAS, was founded in 1998 under the leadership of Evo Morales, in good part growing out of and as part of these struggles.

In the 2005 elections, Morales won the presidency and the MAS a majority in the Chamber of Deputies. The struggle for sovereignty, control over resources and against neoliberalism and U.S. imperialism had now entered into the struggle over the state. These political developments in Bolivia concretized linkages with Venezuela, and the basis for the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América, or ALBA). This has been crucial for building an anti-neoliberal politics, new ideological space for socialism and a counter to American imperialism. But like in Venezuela, the struggle against neoliberalism and the encrusted social structures and inequalities of dependent capitalism have not been so easily overturned. And in particular the existing bourgeois state and capitalist ruling classes in neither of these countries is simply stepping to the side. Indeed, in both cases there is a unique alignment of forces that is producing unprecedented

forms of dual power. In this context, crucial social struggles are bound to break out over the gross inequalities of peripheral capitalism in an era of neoliberalism. In this context, these struggles escape conventional categorizations. They simultaneously reveal the contradictions of neoliberalism, in the stalemate in social power, and the still unfavourable international correlation of forces for socialist advance.

The struggle in the city of Potosi in Bolivia, and the surrounding region, is revealing of all this and more, as the poorest region of Bolivia, the centre of mining and resident to mass indigenous and peasant communities. Potosi is also, of course, the historical silver mines ruthlessly exploited by European colonialists.

The Bullet here presents two takes on the struggle in Bolivia from two of the most important socialist commentators on Bolivia in English, Jeffery Webber and Federico Fuentes, both spend a great deal of time in the region as well as Bolivia. — Socialist Project

Bolivia: Social Tensions Erupt

Federico Fuentes

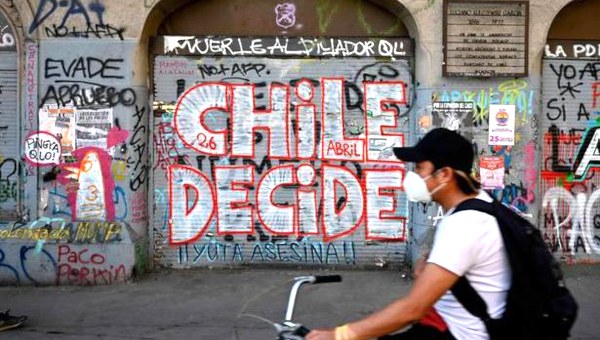

Recent scenes of roadblocks, strikes and even the dynamiting of a vice-minister’s home in the Bolivian department (administrative district) of Potosi, reminiscent of the days of previous neoliberal governments, have left many asking themselves what is really going on in the “new” Bolivia of indigenous President Evo Morales.

Since July 29, the city of Potosi, which has 160,000 inhabitants, has ground to a halt. Locals are up in arms over what they perceive to be a lack of support for regional development on the part of the national government.

Potosi is Bolivia’s poorest department but the most important for the mining sector, which is on the verge of surpassing gas as the country’s principal export because of rising mineral prices.

Indigenous Quechua protesters blockaded the main road between La Paz and Potosi on August 8.

Julio Quinonez, a miners’ cooperative leader told El Diario on August 4: “We don’t want to continue to be the dairy cow that the other regions live off as they always have. Potosi can move forward whether through independence, federalization or autonomy as established in the constitution.”

Local media reported that 100,000 people attended a rally in the city of Potosi on August 3. A hunger strike was initiated that swelled to include more than 600 political and social leaders, including the governor, some local deputies aligned with Morales’ Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) and 20 sex-workers.

The trigger for the protests was an age-old dispute over departmental boundary demarcations with neighbouring Oruro following the discovery that a hill in the area contains minerals used to make cement.

Locals are demanding the government invest more in the region, frustrated that the government has not resolved the daily problems of a poverty-stricken region with an infant mortality rate of 101 in every 1000 babies born – despite sitting on 50% of the world’s lithium.

Local Demands

They are proposing the construction of a cement factory, the completion of a road between Potosi and the department of Tarija, the reopening of the Karachipampa metallurgical plant and an international airport for what is one of Bolivia’s premier tourist destinations.

Another demand is the preservation of the Cerro Rico. These legendary mountains overlooking the city of Potosi used to hold the world’s largest silver mine. Now it is in danger of collapsing as a result of centuries of rapacious looting dating back to colonial days, when Potosi was the same size as London and financed much of Europe’s development.

Locals have occupied an electricity plant and threatened to cut off supplies to the nearby Japanese-owned San Cristobal mine – the largest in Bolivia. Supplies of food and other essentials are beginning to run extremely low. Many roadblocks have been lifted, but negotiations between the government and local authorities stalled as they demanded that Morales himself, and not his “right-wing” ministers, come to the table.

Meanwhile, locals in Uyuni in the south of the department, home to the famous salt lakes and Bolivia’s lithium reserves, voted on August 12 to blockade roads against the protests being organized by the Potosi civic committee. They claim the civic committee wants a lithium processing plant to be built closer to the city so that it solely benefits the city of Potosi. They are also demanding that the government install an interconnected electrical system in Uyuni and build a Uyuni-Huancarani highway.

These protests have been preceded by similar, though smaller protests, by workers over wages, clashes in Caravani between rival local peasant organizations over the site of a new citrus processing plant and a march by Amazonian indigenous peoples demanding consultation before any state activity to exploit natural resources.

These are warning signs of some of the challenges that the process for change underway in Bolivia faces. To understand the protests it is necessary to look at the relationship that exists between social movements, the government and Morales.

Background

The MAS, or Political Instrument for the Sovereignty of the Peoples (IPSP), as it was originally known, emerged both as a result of the process of decentralization of Bolivia’s political system through the creation of municipal councils and local National Assembly deputies in the early 1990s, as well as the crisis that the political system underwent around the same time.

With the old ruling political parties in a state of terminal decay and the old left-wing groups having either disintegrated or incorporated itself into the traditional party system, it was Bolivia’s rising indigenous and peasant organizations that gave birth to their “political instrument” with the aim of entering the electoral arena and moving from resistance to power.

The core of this new political instrument was the peasant confederation, CSUTCB; the “Bartolinas,” a peasant women’s confederation; the colonizers confederation, CSCB (now know as intercultural communities, CSCIB) and the coca growers of the Chapare, from whose ranks Morales emerged.

Through winning control of a number of local councils and seats in congress, the cocaleros became the core around which the various regional and sectoral organizations would coalesce in the late 1990s to make up the IPSP (more commonly known as MAS, its electorally registered name).

In 2000, an important cycle of revolutionary struggle exploded, beginning with the opposition to water privatization in Cochabamba and uprisings in support of indigenous self-determination in the Aymara highlands.

The first wave of this cycle peaked with the overthrow of the president Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada in October 2003, when a diverse range of worker, peasant and indigenous organizations first united against the government’s attempts to cheaply export the country’s gas via Chile. The movement demanded the president’s resignation following the massacre of more than 60 people.

A second wave of resistance brought down his successor in June 2005, again with diverse organizations uniting around the issue of gas. This paved the way for Morales’ victory in December 2005 presidential election, with a historic 54.7% of the vote.

Fierce resistance from the traditional elites, who felt they were being pushed out of power, triggered the third, most powerful revolutionary wave in this cycle of struggle.

Bunkered down in the wealthier eastern states, the right-wing opposition set off a chain of events aimed at overthrowing Morales. However, the combined action of Morales’ government, the social movements and the armed forces crushed the coup attempt in September 2008, a blow the opposition has yet to fully recover from.

Ironically, while its electoral base grew to 64% in December 2009, the MAS itself was greatly weakened.

The MAS was born in the countryside, where the structures of the “political instrument” and the powerful peasant and indigenous organizations were one and the same. But it began to expand into the cities following its 2005 victory, where social organizations are much weaker and individual affiliation prevailed.

In many cases, due to the lack of trained professionals in the peasant and indigenous organizations, Morales was forced to rely on “invitees” from the already existing state bureaucracy to run the government.

Most of Morales’ first cabinet came from these sectors, causing concern among the founding organizations of the MAS, who felt they were not being treated as they should be, with quotas in the government.

While the relatively autonomous social organizations united to defend “their” government during times of intense confrontation, they have also tended to retreat to more local and sectoral demands.

Now in government, many of these groups began to view the MAS as a vehicle to access employment in the public service, just as the middle classes did with their parties when they were in power.

The absence of internal structures in the MAS that could allow a debate over its future led to it becoming increasingly irrelevant as anything more than a place to look for work.

Above all this stood Morales: at the same time as leading the process of change, he is head of state, head of the MAS and even continues to head the cocalero union in the Chapare.

With a debilitated MAS, Morales increasingly plays the role of mediator between ministers, social organizations, party leaders, militants, and “invitees.” This created the rise in demands on the government by various sectors, who having supported “their” government through the intense battles of the last few years, now want it to resolve all the problems inherited from centuries of colonialism.

Here the government is encountering a number of challenges. There is a state bureaucracy which works more to undermine than advance the government’s projects and social organizations with political baggage inherited from the previous society. The government points out it is impossible to resolve century-old problems overnight.

According to an August 9 article by Pablo Stefanoni, Morales outlined the fight against narco-trafficking and contraband, low levels of public investment, personal ambitions and the industrialization of natural resources as key problems. “It is in the construction of the state that the success or failure of the reforms underway will play out,” Stefanoni said.

But to do this, it is vital to reconstruct a political instrument that can truly become a space for the exchange of debates and ideas about the future of the process, capable of generating proposals and uniting the necessary forces to implement a coherent project of change.

Otherwise, indecision, improvisation, inaction and incoherence will continue to plague Bolivia’s process of change. •

This article appeared in Green Left Weekly.

The Rebellion in Potosi:

Uneven Development, Neoliberal Continuities, and a

Revolt Against Poverty in Bolivia

Jeffery R. Webber

The streets of the city of Potosi, 600 kilometres southeast of the capital of La Paz, are desolate, distended with the uncollected garbage of 18 days of a general strike and popular revolt against poverty. Over 700 vehicles are trapped in road blockades at Villa del Carmen, Betanzos, Chaqui, Dan Diego and elsewhere, separating Bolivia’s poorest department (state) from its neighbouring territories, as well as from Argentina and Chile.

Stores are closed, and public and private institutions boarded up, along with schools, markets, and banks. Cash machines are out of money, food and fuel supplies are low, and inflation is lifting the prices of remaining basic commodities into the clouds. Only vehicles authorized by Potosi’s Civic Committee – the umbrella organization through which the protests have been organized – are permitted to navigate the streets, although some Potosinos, as residents of this city of 160,000 are known, make their way on bikes and motorcycles through the few internal streets that remain passable. The dynamite of miners is set off from time to time to remind people that this is a city in revolt, even if negotiations with the government – after six aborted efforts – have finally begun in the neutral city of Sucre.

The Poor Shut Things Down

The avenues and alley ways of Potosi are adorned with red and white – the colours of the department – and roughly 500 blue tent stations are scattered in different locales, providing shelter for possibly 1,000 people on hunger strike, including the governor, who is a member of the ruling party but has temporarily broken ranks under grassroots pressure.[1] Two MAS congress persons also joined the hunger strike initially, but were then successfully pressured into abandoning that route by higher-ups in the party.

In recent days, over 100,000 people have taken to the streets in marches. Peasants from nearby Jatun Ayllu Yura (independent indigenous community) physically occupied the hydro-electrical station that supplies power to the biggest mine in the department, San Cristóbal, run by a Japanese multinational, and the site of major worker and peasant disputes earlier this year.[2] San Cristóbal is losing $2-million (U.S.) per day in exports. $500-thousand (U.S.) is lost daily from the cooperative mining sector. Tourism is dead in Potosi, at the peak of its season (unless we count the few beleaguered backpackers still stuck in the area). “This is going to affect the entire Gross Domestic Product (GDP),” said Minister of Economy and Finance, Luis Arce, a prestigious expert in the inane and obvious. “We hope that the conflict will be resolved so that it will not have major economic impacts on the country.”[3]

The protests began on July 30 with a 48 hour general strike to drive home popular disaffection with the government’s failure to respond to a series of electoral commitments made to the destitute department. These agreements had first been outlined in a petition delivered by the Civic Committee to Morales back in 2009. The 48 hour strike was extended to an ongoing action with indefinite end when the government’s response was silence.[4]

The favoured government tactic has been to exhaust the strike through inattention, but this has seemed only to radicalize and broaden the base of support for Potosi’s militancy around six principal, immediate demands: (1) resolution of department borders between Potosi and Oruro, particularly around the mountain of Tahua, rich in the rock base used for cement production; (2) the immediate installation of a promised cement factory in the community of Coroma, to create jobs; (3) the reopening of a metal processing plant in Karachipampa; (4) the structural preservation of the over-mined Cerro Rico (the massive, historically and symbolically crucial mountain that towers over the city of Potosi); (5) the construction of an international airport in the department to attract tourism; and (6) the completion of promised highways.[5]

So we’re dealing with the poorest department in the country (where life expectancy is dramatically below the national average), which gave roughly 80% support to the MAS in the last elections, rising up in a protest against neoliberal continuity and the failure of basic responses to endemic poverty.

The class character of the protest is complex. Some of the leadership is clearly composed of cooperative miners. The richer layer of the cooperative miners is basically constituted by reactionary petty capitalists working together with transnationals in Potosi against the rights of state-employed miners.[6] Also in the leadership are other sectors that might accept merely a clientelistic buy-out by the MAS to “solve” the situation.

But the rebellion has matured into something much, much larger. Eighteen days of general strike (total lockdown of the city) and a thoroughly impenetrable regime of coordinated road blocks are not easily carried out absent mass popular support. While ostensibly led by the Civic Committee of Potosi, in which the cooperative miners play a partially determining role, the sectors in revolt also include communities of indigenous peasants, various unions of the formal working class, the informal urban poor, organized sex workers, university students and professors, artists and intellectuals, and even the city’s soccer team.[7]

“The historical necessity of the region, to which no government has ever attended,” sociologist José Mirtenbaum suggests in a recent op-ed, “produces these types of just and legitimate demands, which speak to all citizens. The qualitative magnitude of the historical causes are too enormous to measure. It’s absolutely legitimate that a population takes to the streets to reclaim their natural resources and for other demands that have much to do with their symbols,” as a people.[8]

Neoliberal Mining and Uneven Capitalist Development

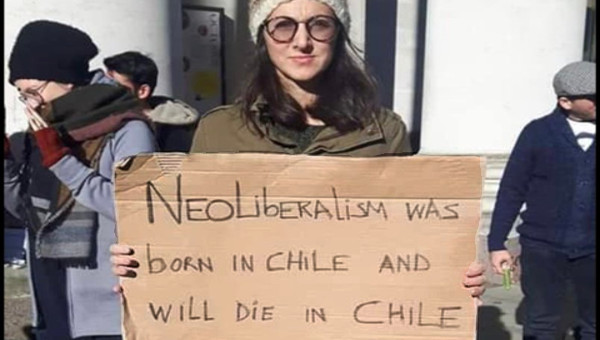

“In search of profit and driven to compete,” Marxist geographer Neil Smith reminds us, “capital concentrates and centralizes not just in the pockets of some over the pockets of others but in the places of some over the places of others.”[9] With the crash of tin prices in 1985 and the onset of 15 years of brutal neoliberal restructuring in Bolivia, capital increasingly vacated the impoverished department of Potosi – once the silver capital and slave graveyard of the Spanish Empire – and entered the new dynamic centre of Bolivian accumulation – the agro-industrial, hydrocarbon-rich, and narco-fuelled right-wing heartland of Santa Cruz.

However, with the onset of the commodities boom in 2002, and still today, even in the midst of the ever-mutating global crisis, transnational capital has found its way back to mineral-rich Potosi. Unfortunately, with the continuity of neoliberal mining policy under the government of Evo Morales, the bulk of the wealth generated by mineral exploitation continues to be repatriated to imperial countries outside of Bolivia, leaving only poverty, unemployment, regional underdevelopment, and environmental contamination in its wake.

This is the backdrop to the extraordinary and ongoing popular revolt against poverty we’ve witnessed in Potosi since it first broke out, 18 days ago, on July 30, 2010. Again, the crux of the situation is that the mining regime that prevails in Potosi, as elsewhere in the country, is fundamentally neoliberal, and that this is a MAS strategy, not a deviation from their plan, or a distortion by disgruntled state bureaucrats, leftover from old regimes.[10]

For example, a recent study of a Canadian subsidiary, Pan American Silver, operating in the department through a shared-risk contract with the state company COMIBOL (COMIBOL effectively controls about 30% of the project), shows that the company will pay merely 17% taxes and royalties on projected gross sales value over the next 30 years. The taxes going to the municipality where the company is located, one of the poorest in the country, are just over 0.5%. This is straightforward looting. By comparison, in various shared risk contracts in Chile (hardly a socialist haven) taxes and royalties going to all levels of the state amount to up to 51%, whereas, in Peru, it’s on the order of 26%.[11]

The hegemony exercised by transnational capital in the mining sector in Bolivia calls into question the viability of the Morales government’s commitment to “harmony” and “equity” between different forms of property (state, private, communitarian, and cooperative), or what it terms a “plural economy.” Vice-President Álvaro García Linera has theorized the independent development paths of different forms of property under the rubric of “Andean-Amazonian Capitalism,” but his theory resolutely fails to account for the overwhelming dominance and power of private property – under the control of transnational capital – in the underdeveloped capitalist socio-economy of Bolivia. In mining, the role of COMIBOL has been entirely marginalized and the power of transnational mining capital to loot continues unabated.[12]

Reconstituted Neoliberalism

Neoliberal continuities in Bolivia’s political economy under Morales are not restricted to mining, and this is increasingly evident to perceptive thinkers from across the political spectrum. “What has changed in these last few years,” asks Roberto Laserna, one of Bolivia’s most renowned neoliberal intellectuals. “A lot, if one observes the process in terms of its discourse and symbols and maintains a short-term perspective. But very little if one is attentive to structural conditions and observes the economic and social tendencies with a longer-term view.”[13] I rarely agree with Laserna, but on this point he is precisely on target.

Most of Morales’ first four years can be described, from an economic perspective, as high growth and low spending. Prior to the fallout of the worldwide economic crisis, which really started to impact the Bolivian economy in late-2008 and early-2009, the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) had grown at an average of 4.8 per cent under Morales. It peaked at 6.1 per cent in 2008, and dropped to an estimated 3.5 per cent in 2009, which was still the highest projected growth rate in the region. This growth was based principally on high international prices in hydrocarbons (especially natural gas) and various mining minerals common in Bolivia.

Government revenue increased dramatically because of changes to the hydrocarbons tax regime in 2006. But fiscal policy remained austere until the global crisis struck. Morales ran budget surpluses, tightly reigned in inflation, and accumulated massive international reserves by Bolivian standards. Public investment in infrastructure, particularly road building, increased significantly, but social spending rose only modestly in absolute terms, and actually declined as a percentage of GDP under Morales.

Fiscal policy changed in 2008 and 2009, as a consequence of a sharp stimulus package designed to prevent recession in the face of the global crisis. The social consequences of reconstituted neoliberalism – whatever the rhetoric of sympathisers on the international left – have been almost no change in poverty rates under Morales, and deep continuities in social inequality. Both of these axes persist as monumental obstacles standing in the way of social justice in the country.[14]

The realities of these dynamics do not escape even some hard-line supporters of the government, such as Ariel Vergara Garnica, Excecutive Secretary of the Federación Sindical Única de Trabajadores Campesinos de Tarija (Federation of Peasant Workers of Tarija, FSUTCT). In a recent interview, after praising the government’s respect for human dignity, responsible development, and Mother Earth, Vergara Garinca was asked about the economy under Morales: “Bolivia has grown economically at a rate of approximately 4 per cent [under Morales]; however, in spite of the fact that many say that this growth has brought big economic benefits for Tarija [a hydrocarbons-rich department in the eastern lowlands], these aren’t being felt by the people, because they have been concentrated in a few hands, and have never reached the general population.”[15]

At the same time, this dynamic has been recognized recently by no less an establishment authority than the World Bank Director for the Andean Region, Felipe Jaramillo. In an exclusive interview with La Paz daily Página Siete this week Jaramillo did begin with a call for improvement in the Bolivian investment climate – an aural tick not easily cast aside after years spent as a PhD student in the economics department of Stanford, followed by a stint as Vice-Minister of Finance in Colombia, and then World Bank posts in Asia and Europe.

Grounding himself in the data, however, Jaramillo praised the macroeconomic management of Morales, particularly his government’s fiscal and monetary austerity, commitment to extremely low inflation, and unprecedented accumulation (by Bolivian standards) of international reserves.[16] This assessment explains why, earlier in the week, the World Bank agreed to provide Bolivia with $150-million (U.S.) in concessional loans for various projects, loans which are of course subject to a series of neoliberal conditionalities with which the Morales government appears set to comply. The same is true of a $30-million (U.S.) loan from the Inter-American Development Bank agreed to simultaneously.[17]

The Rupture in Potosi and the Rising Discontent of the Popular Classes

Bolivia’s nine departments.

Negotiations have now started with the government in Potosi, but it’s hard to exaggerate the significance of this break with the MAS, and the ways in which the government’s populism will be unable to contain the growing discontent from urban and rural popular classes.

For example, the factory workers of La Paz, who supported the MAS officially in the December 2009 elections, have now distanced themselves from the government. This was made clear in a series of strike actions in April and May 2010, alongside urban teachers, miners, and health care workers.[18] The political-ideological orientation of the Federation of Factory Workers of Cochabamba, led by former shoe-factory worker Oscar Olivera, reflects an even deeper schism with Morales.

The powerful urban indigenous-proletarian organization, FEJUVE-El Alto (Federation of Neighborhood Councils of El Alto), for the first time in four years, has changed course. Following recent elections, the new leadership has a mandate to follow the latest set of resolutions, drafted at a Congress at which thousands of representatives from the impoverished neighbourhoods of El Alto had a voice. The new resolutions state explicitly that this government represents neoliberal continuity;[19] three members of the new executive board come from a recently-established revolutionary federation of neighbourhood councils in the city.[20]

There will be major conflicts, possibly large-scale strikes, over the proposed pension law which is abysmal and which will affect the entire formally-employed working class. Further demonstrations are also likely to grow around the government’s new hard-line approach to cracking down on “contraband.” Whereas many on the left would be on board with measures against contraband mafias and narco-trafficking thugs, the reality in Bolivia is that the new measures are going to throw tens of thousands of informal workers out of work with no alternative means of employment.

Other prominent breaches between the government and popular organizations emerged this year. Particularly salient were those with the lowland indigenous organization, CIDOB, which the government accused of being a puppet of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the coca growing peasants of the Yungas region of the department of La Paz, which split with the government after a dispute between peasants and the Morales administration over development projects in Caranavi.

These fractures between the popular classes and a government that continues to insist it represents them are very distinct phenomena from the right-wing destabilization campaigns in Sucre, Santa Cruz, and Tarija in the last few years, or the related peasant massacre in the community of Porvenir, carried out by functionaries of right-wing governor of the department of Pando on September 11, 2008. The government, in this context, was correct to assume a gladiatorial stance against imperial meddling. In the latest face-offs with popular groups, the fantasy that the discontent of the exploited and oppressed has simply been artificially engendered by Empire reflects an unsavoury attachment by elements of the Morales administration to the Stalinist witch hunts of the past.

While committed to the defence of the Morales administration against destabilization campaigns from the domestic right and various imperialist forces, these popular currents are also beginning to believe that the break with neoliberalism actually introduced in recent years has been exaggerated by the Morales administration. Rather than waiting for transformative change to come from on high in the form of state officials aligned with the MAS, the new struggles are reclaiming agency – an agency rooted in the struggles and capacities of the exploited and oppressed themselves, working independently from the MAS.

The ability of Morales to play the distant saviour, to reduce recurrent instability to mere manifestations of internal party problems, “bad-apple” ministers, disloyal bureaucrats, and social movements manipulated by nefarious CIA and NGO agents, is losing plausibility rapidly amongst the population. As much as he deigns to, Morales cannot stand above the class struggle and inherent contradictions in the capitalist development model to which his government has wedded itself.

At the moment, the Bolivian President is attending the Social Forum in Paraguay as a special guest, while several of his top Ministers are back at home in Sucre attempting to resolve the crisis in Potosi.[21] It is likely that a short-term agreement will be hashed out and temporary stability restored. However, unless the Morales government takes the unlikely turn toward abandoning its bourgeois alliances and committing itself to the authentic anti-capitalist and indigenous-liberationist demands of the popular revolts of the 2000-2005 insurrectionary cycle, the Potosi uprising is likely just the beginning of things to come.

Jeffery R. Webber teaches politics at the University of Regina, Canada. Beginning in September, 2010 he will be a Lecturer in the School of Politics and International Relations at Queen Mary University of London. He is the author of Red October: Left-Indigenous Struggles in Modern Bolivia (2010), and From Rebellion to Reform in Bolivia: Class Struggle, Indigenous Liberation and the Politics of Evo Morales (2011). He is currently in La Paz, Bolivia.

Footnotes

1.

“La Villa Imperial está unida, movilizada y desabastecida,” La Razón, August 12, 2010; “El Gobernador de Potosí está en terapia intensiva,” La Razón, August 12, 2010; “Hay ministros que no están con el proceso de cambio,” La Razón, August 11, 2010; “Conflicto en Potosí es el más largo desde la caída de Goni,” Pagina Siete, August 14, 2010.

2.

Juan Carlos Véliz, “El diálogo naufraga y Potosí radicaliza sus movilizaciones,” Página Siete, August 11, 2010; “Minera San Cristóbal para labores con pérdidas día de $2-millones (U.S.),” La Razón, August 12, 2010.

3.

“El conflicto afectará el crecimiento económico,” La Razón, August 14, 2010.

4.

Eugenio Paz, “Demandas históricas irresueltas,” Página Siete, August 14, 2010.

5.

Editorial, “Potosí sin salida,” Pulso, August 15, 2010.

6.

This layer, for example, often no longer engages in direct mining activities, but rather hires poor “cooperative” miners at super-exploitative wages. The rich layer of cooperative miners has even become known as the “nueva rosca,” or the new mining political-economic elite of the region. See Jaime Chumacero, “Potosí entre la eterna frustración y su incierta combatividad,” Pulso, August 15, 2010.

7.

“Conflicto en Potosí es el más largo desde la caída de Goni,” Página Siete, August 14, 2010; “El Origen del conflicto fue la caliza,” Página Siete, August 14, 2010.

8.

Jose Mirtenbaum, “No se puede medir la magnitude,” Página Siete, August 14, 2010.

9.

Neil Smith, “The Geography of Uneven Development,” in Bill Dunn and Hugo Radice, eds., 100 Years of Permanent Revolution: Results and Prospects, London: Pluto, 2006, p. 189.

10.

For an alternative view, see Frederico Fuentes, “Bolivia: Social Tensions Erupt,” The Bullet, August 20, 2010, available online at:bullet/404.php.

11.

Juan Collque and Pablo Poveda, “Hegemonía transnacional en la minería boliviana,” Le Monde Diplomatique, edición boliviana, agosto de 2010.

12.

Juan Collque and Pablo Poveda, “Hegemonía transnacional en la minería boliviana.”

13.

Roberto Laserna, “El cambio que no cambia,” Pulso, August 8, 2010.

14.

Drawing on data from Bolivia’s National Institute of Statistics, the best study thus far charts poverty and extreme poverty trends up to 2007, which are the latest available figures. The study notes that since 2005 there has been only marginal change in the poverty rate, and that this change has been slightly upward, from 59.9 per cent of the population in 2005 to 60.1 per cent in 2007. Levels of extreme poverty increase from 36.7 to 37.7 per cent over the same two year period. At the same time, other categories relevant to living standards highlighted, such as household density, and access to electricity, running water, and sewage systems, all show modest improvements between 2005 and 2007. It is possible that poverty levels have improved since 2007, and it should also be noted that these figures do not take into account improvements in the social wage of workers and peasants – i.e. any improvements in social services for the poor. Again, however, social spending has actually declined as a percentage of GDP under Morales, even as it increased in real, inflation-adjusted terms. The record on poverty shows that there is little to celebrate. The key data here is derived from Mark Weisbrot, Rebecca Ray, and Jake Johnston, Bolivia: The Economy During the Morales Administration, Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, December 2009, p. 16. It ought to be noted the poverty figures from ECLAC do not correspond with the figures discussed here. The latest ECLAC publications provide national figures for 1999 and 2007, and claim that there has been a downward shift in Bolivian poverty from 60.6 per cent poverty to 54 per cent poverty between these years. See ECLAC, Anuario Estadístico de América Latina y el Caribe, 2009, Santiago: ECLAC, 2009, p. 65.

Inequality, likewise, remains a huge barrier to achieving social justice in the Bolivian context. Between 2005 and 2007 income inequality, as measured by the Gini Coefficient, declined from 60.2 to 56.3. Figures for the distribution of Bolivian national income show that the poorest 10 per cent of the Bolivian population received 0.3 per cent of national income in 1999, and still received only 0.4 per cent by 2007, the last available figure. Meanwhile, the richest 10 per cent of the population took home 43.9 per cent of national income in 1999 and precisely the same percentage in 2007. If we broaden our perspective, to compare the bottom and top fifths of the social pyramid, we reach similar conclusions. The poorest 20 per cent of society took in a mere 1.3 per cent of national income in 1999 and, in 2007, a still-paltry 2 per cent. The richest 20 per cent of the population pocketed 61.2 per cent of national income in 1999 and 60.9 in 2007. In other words, there has been almost no change on either end of the scale in terms of the redistribution of income, never mind the redistribution of assets. See, Mark Weisbrot, Rebecca Ray, and Jake Johnston, Bolivia: The Economy, p. 18 for inequality figures employed here.

15.

Quoted in Danitza Pamela Montaño T., “La economía, el reto para consolidar el nuevo Estado,” Pulso, August 8, 2010.

16.

“ ‘Hay que mejorar el clima de inversión’: El máximo del Banco Mundial en la región mira a Bolivia,” Página Siete, August 15, 2010.

17.

Demmis Valenzuela, “BM asegura recursos para tres proyectos: Con un aporte de $140-millones (U.S.),” Página Siete, August 11, 2010; “BID entrega $30-millones (U.S.) para apoyar la gestión pública,” Página Siete, August 11, 2010.

18.

Personal interview with Wilson Mamani, Executive Secretary of the Federation of Factory Workers of La Paz, August 11, 2010. Also see, Jeffery R. Webber, “Evo Morales and Bolivia’s Reconstituted Neoliberalism,” International Socialist Review, forthcoming (September-October, 2010).

19.

Raúl Zibechi, “Movimientos-Estados-movimientos,” La Joranda, July 16, 2010.

20.

Personal interview with Carlos Rojas, ex-leader of FEJUVE-El Alto, August 10, 2010.

21.

“El diálogo avanza pero Potosí mantiene el paro y el bloqueo,” Pagina Siete, August 15, 2010; “IV Foro Social: Presidente Morales viaja a Paraguay,” Página Siete, August 15, 2010; “El diálogo se abre en Sucre, pero sigue el paro y bloqueo,” La Razón, August 14, 2010.