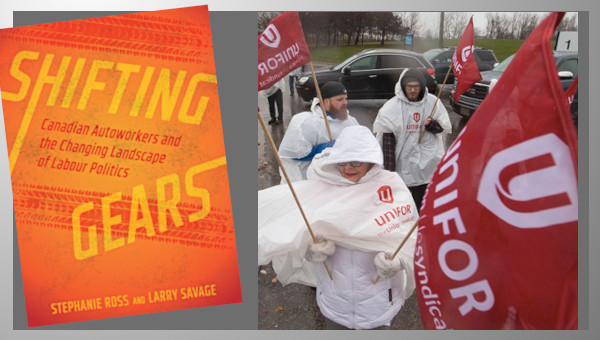

Ford Canada Concessions: Could it Signal the End of an Era?

While the CAW and Ford enter into another round of concessions bargaining – in the wake of concessions in the UAW – there is an argument to be made that the time for trading concessions for promises of investment and jobs should be ending. These two pieces argue for such an outcome. The first, by retired CAW National Representative Herman Rosenfeld calls for a movement that makes Ford the new pattern. The second, by former Ford Oakville worker Euan Gibb, describes the successful effort to oppose concessions at CAW Local 707 in 2008.

The Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) and the Ford Motor Company have been engaged in contract talks, scheduled to resume formally on October 26th. Ford is demanding that the union give up the same package of concessions that workers at GM and Chrysler gave up last spring, as part of the conditions of those companies receiving government aid. The union is demanding that Ford commit to maintain a specific proportion of investment in Canada as a condition of agreeing to concessions.

At that time, workers at GM and Chrysler agreed to reductions in time off the job, job intensity protections, rights for new hires, as well as adding new monthly co-payments for drug and benefit plans. That was on top of a previous set of early bargained concessions – said to be worth $300-million by the CAW leadership at the time – given up in 2008 before the current crisis even began. At that time workers at Ford Oakville voted to reject these concessions, but were forced to accept by large majorities at other Ford units.

Ford hasn’t asked for or received bailout money from the U.S. and Canadian governments (although it has had access to a range of auto sector subsidies over the last few years). The company borrowed from private sources and engaged in a process of restructuring before the near failure of the other two. Since then, it has been more than able to hold its own in the face of the ongoing crisis. The company has so far refused any commitment to maintain investment or jobs here

After being pressured into giving up concessions a number of times, workers at Ford in auto plants in both the U.S. and Canada are tired of the threats and broken promises. There is no need to match the takeaways bargained and imposed at Ford’s U.S.-based competitors. Instead, Ford’s collective agreement can become the basis of a new pattern in the industry. Canadian autoworkers can take the lead in making it happen. It’s time to put an end to the era of concessions.

Concessions Fatigue

Ford UAW representatives meeting in late August told the American union’s leaders that the workers there were tired of being asked to give up past gains in exchange for false promises of jobs and investment. They reported that workers are suffering from what they called ‘concessions fatigue.’ Taking back white collar staff concessions at GM last month only reinforced this. The UAW leaders were forced to back off – at least for the time being – from accepting company demands for concessions. Unfortunately, last week the UAW leadership bargained a new tentative agreement with $500-million in new concessions. It remains to be seen how the membership responds.

Impossible Trade Off

Ford will not guarantee investment levels or jobs, so the trade-off of concession for jobs is not credible. Ford’s shareholders are opposed and want the company to take a hard line. Ford’s overall investment levels are being reduced, although the U.S. agreement reportedly includes future product commitments at five assembly plants there. In any case, there is no way to force the company to live up to commitments it might make through collective bargaining, as seen in the recent past at the GM truck plant and at Chrysler.

Given this situation, demands that Ford guarantee a specific level of Canadian investment in exchange for concessions either won’t work or can only result in vague promises that have little real meaning. In the latter case, workers would be left with more concessions in exchange for nothing. Workers are increasingly realizing this, making it difficult to get ratification votes for a new round of takeaways. This puts pressure on the current CAW leadership that seems committed to applying the latest round of concessions to Ford.

Challenging Ford’s Claims

Ford’s arguments don’t hold water and need to be challenged. While globalization gives corporations power, comparing Canadian labour costs with those in India, Mexico and China is irrelevant. Canadian workers can never compete with those costs and no amount of concessions would change that. Claims that Canadian labour costs are the highest in the world are also not credible. German hourly costs remain higher, particularly considering productivity levels. Comparisons with American costs are also problematic: even the CAW has argued that workers have yet to be hired at the lower wage rates promised in the 2008 agreements; productivity levels remain higher in Canadian plants and the rise of the loonie is a temporary factor that can be addressed politically and affects all of the companies. Finally, labour costs are less than 10% of the cost of vehicles.

Ford has fared the best among the U.S.-based auto companies during the current crisis. Sales have been higher. Its losses have been smaller. Industry analysts and Ford executives have predicted market share increases and greater prospects for success for the company as the crisis period ends and the auto market picks up. It is true that Ford’s American competitors have had their debt loads eliminated by the bankruptcy procedure while Ford’s have not. Ford’s debt obligations cannot be addressed through labour cost adjustments or collective bargaining.

Workers at Ford do not need to cut their incomes, benefits, reduce their break times or increase their workloads – as workers at other companies have been forced to do – in order to allow the company to survive. Like GM and Chrysler, longer term survival has nothing to do with labour costs, but is based on more fundamental factors that need to be addressed through a program of economic and political demands. The CAW needs to develop a new approach to the sector, one that takes into account the requirements of the environmental crisis, and seeks to cut the dependency on the competitive success of individual corporations.

Options

The current situation is a difficult one for a union leadership that seems committed to concessions: it can’t count on real guarantees from Ford for new investment and workers have become increasingly wary about ratifying new concessions even with them. The unprecedented rejection by the Oakville Local 707 of the last concessionary agreement in 2008, and the close vote at CAMI last month, where only 60% of the production workers ratified similar contract modifications and there was a mood of anger and impatience, have to be weighing on their minds.

There is an option for the union that would have to be driven from below. Workers at Ford-Canada should refuse any new concessions and demand that the current agreement (itself containing concessions bargaining in 2008) should remain in place until it expires in 2011, renegotiate it or extend it for an extra year at that time and use it as a new pattern for GM and Chrysler to match. They should be supported by workers at GM and Chrysler. All have an interest in maintaining the gains of Ford workers and an end to the concessions strategy. When the next round of bargaining begins, they should demand that GM and Chrysler match Ford. That might also inspire American workers and begin a process of moving forward.

This challenges those who argue that pattern bargaining requires Ford workers to fall into line with the other companies. Pattern bargaining was instituted in order to force all competitors to maintain the highest negotiated standards of wages, benefits and working conditions – not the lowest. Assuming that the auto market will be in healthier shape at that time, it provides an opportunity to move away from the U.S. government-imposed set of concessions, which, after all, were tied to the cost structure of the non-union Japanese-owned transplants. If the goal is to organize them, it would only make sense to show workers there that the union stands for something better than they already have. If not, why would they want to join a union?

If Canadian CAW autoworkers want to win a new pattern, they will have to organize for it. The time between now and the next round of bargaining must be filled by creating the conditions for challenging the companies. There needs to be a campaign which argues that the era of concessions is over and educates and mobilizes across the entire auto sector – including at the suppliers – to collectively engage activists, their co-workers and people in the communities. The lack of any real campaign to challenge the corporate-driven propaganda about labour costs which preceded the bankruptcy crisis contributed to the isolation of autoworkers and the defeat.

There is an amazing diversity and potential among the union’s activists, staff and elected representatives. The CAW has the capacity to pull off a campaign of reframing, organizing and building a movement plant-by-plant, member-by-member, instead of retreating and trying to defend smaller and smaller pieces of what remains.

Ford, Chrysler, GM and the auto parts plants need to organize across their locals. Simply allowing the contract to expire in 2011 without building an anti-concessions campaign will only postpone the problem – even if the market picks up dramatically. It would make it harder to respond to the companies when they argue that they need new concessions in order to be able to respond to the competition of the transplants. If the market doesn’t pick up, not building resistance now would make it easier for the leadership to take advantage of the fear and insecurity of the members. •

How Local 707 Oakville Activists

Led a Movement Against Concessions

Euan Gibb

The present demand for more concessions from the UAW and CAW, and the ‘concession fatigue’ of workers, needs to be understood in context. This is the story of what can be accomplished if we work together to defeat concessions.

There were two plants in Oakville, just west of Toronto on Lake Ontario, until a few years ago. The truck plant that had been there since the sixties was closed in June 2004 and there was no new product for the (then) van plant. In this context of job fear, the company used the now familiar strategy of blackmail in 2006. Workers at the plant were told to vote yes for a package of concessions or Ford units in Hermosillo, Mexico or Atlanta, Georgia would get the new product.

Local union leaders effectively delivered the message of the company and told workers that now was not the time to fight. Some of the reps made the case that workers would be able to turn things around once the new product was in the plant. Concessions included a reduction in the number of in-plant union reps, reduction of inter-departmental bidding rights reduced break time and outsourcing of cleaner jobs (high seniority jobs off the line). Despite the fact that this Oakville plant eventually got the investment (that many suspected would have occurred anyway) things did not turn around. Oakville was converted to a modern ‘flex’ plant where multiple vehicles are produced from the same assembly line.

Then they came for more concessions in 2008. Workers were being told that we should vote yes in solidarity with workers in Windsor and St. Thomas. This argument anticipated the ‘manufacturing footprint’ argument that the CAW is now putting forward. But there were no guarantees then either. The media was going crazy with details of what would be given back this time. It included less time off the line, outsourcing some of the shipping/driver jobs, less holidays and a one-time bonus offered in place of the holiday time. The ratification vote was a week away when workers found out about the details of the upcoming demands.

Several workers got together to write and distribute a leaflet in the plant independent of the local union. The central demand articulated in the leaflet was the need for more time – time to discuss what concessions would be accepted if any. A ‘NO’ vote was called for in order to take some time. The entire process had been rushed.

The day of the ratification vote there were a few presentations from the National union before a clear confirmation about what concessions were going to be demanded and the case for acceptance. One of the presentations showed several ‘storm clouds’ appearing over the auto industry including an exceptionally high Canadian dollar, an auto industry going through structural changes and an approaching economic crisis. The case for concessions was restated by outgoing CAW President Buzz Hargrove.

The main problem was that the case on offer contrasted starkly with workers’ known and lived experience in the cyclical auto industry. Mandatory overtime had been in place for months at the plant and the cars that were being made in Oakville were selling like crazy. The presentation did not go well. Workers were angry and felt like they were being patronized. People clearly understood the location of their plant in the broader restructuring of the North American auto sector. Consequently, they didn’t hesitate to articulate their anger during and after the presentations. Speaker after speaker at the microphones argued for a rejection. A few of the elected reps and bargaining team members called for ratification using arguments about loyalty and deference to authority.

People were not convinced. By early evening the results were in – the first rejection of a recommended contract at a major auto plant in the union’s history! The numbers were not overwhelming, but they certainly were unambiguous. This should have provoked the reconvening of the bargaining teams but this never happened. Workers at the other Ford locations in St. Thomas, Windsor and the Bramalea parts depot all voted to accept the offer.

The case was made that these workers ‘swamped’ the Oakville workers’ vote and so the concessions were accepted. However, the collective agreement between the national union and the company clearly stated that workers at ‘each’ location must ratify the contract in order for it to come into force. To workers in Oakville this point seemed like a technicality and not worth trying to engage in a high-stakes internal gamble with uncertain external outcomes. It seemed like the point had been made. •