The Mexican Crisis and the Oaxaca Commune

The Oaxaca Commune was an extraordinary experience of popular insurgency and democratic self-governance. Though its rise and fall was conditioned by the particularities of the Mexican political crisis of 2006, the forms of the struggle have a universalistic relevance. “Assembleist” forms of direct democracy were developed in order to organize both the rebellion and the governing of the city of Oaxaca for the five months that the popular forces controlled the city. This experience demonstrated the tremendous creative potential that can emerge in the course of popular struggle. It also exposed the limitations of rebellion in one region. The pamphlet below is an attempt to understand the experience of the Oaxaca Commune, its strengths and limitations. It also is an attempt to situate the rebellion in the conjuncture of the national crisis, a crisis that created space for the rebellion and, as it was not yet a national revolutionary crisis, set limits on its development and eventually led to its defeat. The national situation allowed the movement to grow but also set boundaries on its potential. The movement was brutally repressed on November 25, 2006, but it has survived – weakened but alive, vibrant, and with great potential.

The Continuing Crisis in Mexico

The crisis of the neoliberal-authoritarian Mexican regime continues to deepen. The regime has very little political legitimacy. Popular discontents exploded in two mass and creative mobilizations in 2006, that of the anti-fraud movement over the Presidential elections, and the Oaxaca insurgency and commune. These two movements, while sharing many of the same roots and hopes, were very different movements. And their failure to coalesce into a broader movement was a key factor in their mutual defeat. Nevertheless, important currents in the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (Party of the Democratic Revolution – PRD) provided linkages between the Oaxacan popular movement and national forces. Now, the deepening crisis – and likely split – of the national PRD could isolate the Oaxaca resistance even more from national struggles.

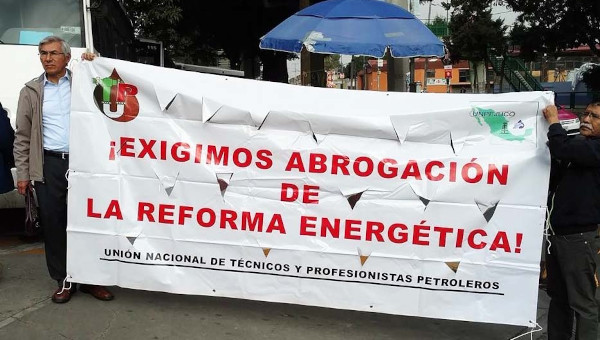

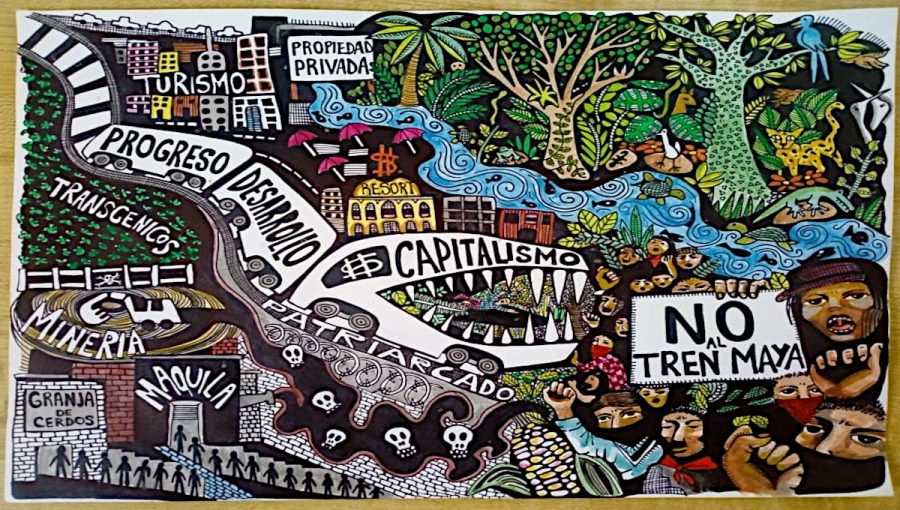

Neither the national crisis nor these two movements have disappeared. The national crisis deepens by the day with the determination of the national government to carry out a slightly-veiled privatization of oil and energy and anti-labour reforms. The tenacity of popular resistance has slowed the neoliberal assault without being able to stop it. The “catastrophic equilibrium” of the Mexican regime continues. Militarization and repression have intensified but popular resistance continues to grow, in spite of continuous repression and the weaknesses and political crises of the left.

State-engineered assassinations, disappearances and arrests have continued on a daily basis in Oaxaca. Some people have remained in jail since that day. The low intensity war against popular movements that started even before November 25, 2006 has continued ceaselessly. It has had a great human toll and, combined with the defeat of the popular insurgency, has led to a significant decomposition of the social order. In addition to the constant violence by the state, there has been a generalization of violence in society. This presents very difficult conditions for the resurgence of mass, open, popular resistance.

The Oaxacan Popular Resistance

Nevertheless, the various components of the Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca (Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca – APPO) continue the battle against repression, authoritarianism and neoliberalism. Section 22, the Oaxacan state section of the teachers union, whose repression initiated the rebellion – and who provided a core of cadre for the popular movement – continues to fight for union democracy, improvements to education, better wages and working conditions, and an end to the ongoing repression. And both section 22 and the APPO play important roles in attempts to form national movements of resistance. The APPO has sought, with some success, to deepen its roots in small towns and the countryside. But the same structures of power and the same repressive governor that the people rose up against continue. None of the problems that gave rise to the APPO have been resolved. Section 22 and the APPO lost the battle in 2006 but the war continues. Major mobilizations are planned for Oaxaca for May that will intensify both the resistance and the repression.

The possibilities for the resurgence of the Oaxacan popular movement will be conditioned by developments both at the state and the national level. The Oaxacan resistance needs a strong national left as an ally but the Mexican left itself is in deep crisis. The defeat of the Oaxaca movement and the escalation and institutionalization of extreme violence in Oaxaca also present extremely difficult conditions for the growth of the Oaxacan movement. There is, however, a continuing vitality to movements of resistance in Oaxaca and no end in sight to the continuing assault of neoliberalism and repression. There is also now a shared memory of democratic, popular insurgency that can play an important role when popular resistance rises to new levels again.

The Oaxaca Commune has added the experience of popular, self-governing insurrection to the repertoire of images, strategies, and processes of struggle in popular consciousness. As things polarize more and more in Mexico, this example could take on even more relevance as an alternative in the repertoire of those in struggle. But for a new Oaxacan rebellion to have any possibilities of success, the Mexican left nationally must overcome its deep crisis. •