Income Inequalities, Living Wages and Union Organizing

It is now accepted across a wide spectrum of political thinking that the period of neoliberalism has sharpened income inequalities. This has occurred along a number of dimensions. The capitalist class has seen an increase in wealth from an increasing concentration of assets; a rapid run-up in asset prices; and corporate profits having been restored to historically high levels. Some professional classes, particularly in the massive financial, legal, accounting, and management bureaucracies that have grown along side neoliberal globalization, have shared in this surge of incomes.

In contrast, for the broad swath of salaried and waged workers there has been general wage compression. This compression has slowly crept into the strongest sectors of the economy, notably Canadian autoworkers have moved in the direction of concessions bargaining, though productivity remains high, the value extracted from workers enormous, and government subsidies vast. At one time the leading force against concessions bargaining in Canada, the CAW leadership is now regularly helping rewrite contracts to accommodate wage and work rules concessions, enabling the auto companies to whipsaw its membership from Oshawa to Windsor to Brampton, and back again. It is hard even to recall when CAW last led a major struggle or strike against the auto companies.

In weaker sectors, pattern bargaining has long been broken, and wage compression and dispersion even more extreme. In the bottom tranches of the labour market, precarious work, high unemployment and the breaking of the link between minimum wages and median wages has added to the numbers of the working poor. And, in a further effort to spread labour market insecurity and bolster profitability, neoliberal policies have actively rolled back the relationship between welfare rates and average income levels. This labour market dynamic has intersected with, and furthered, racial and gender stratifications across Canadian society.

This is a shorthand description of the social processes of capitalist accumulation shaping income distribution today more generally. In Canada, wage pressures have been impacted by continental processes since NAFTA. Such wage compression has encompassed both the U.S., where they have been just as severe as in Canada, and Mexico, where the crisis of living standards and work for the Mexican working classes cannot even be compared with the other two. Mexico fits within the general patterns of income distribution across Latin America under neoliberalism of stagnant or falling per capita incomes for some two decades, 70-80 % of new job growth in the informal sector, and half the population living in poverty.

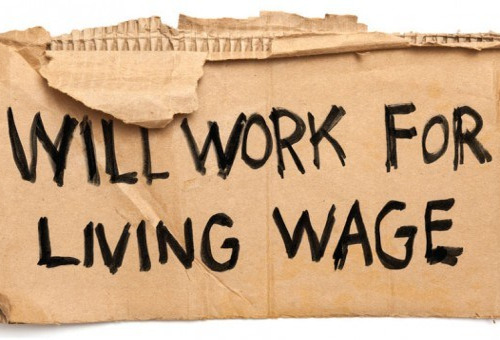

In this context, it is imperative that the left get behind living wage campaigns as one aspect of a response to neoliberalism. The labour movement in Canada has been supporting a $10 minimum wage with key campaigns occurring at the Federal level, in B.C., in Ontario and in Toronto. Other campaigns are also directed at addressing welfare levels, as in the ‘Ontario Needs A Raise Campaign’ of the Ontario Social Justice Network and the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty’s ‘Raise the Rates’ mobilization. In the U.S., there have been numerous successful living wage campaigns targeting the municipal level. And the economic crisis in Mexico has new emergent sections of the labour and social movements coming together to call provocatively for a ‘continental living wage campaign’. A key political question is how to link these campaigns up, and particularly not to separate campaigns for minimum wages apart from ones for welfare rate increases. There is a significant opportunity opening up to unite these struggles and forge major political mobilization across Ontario, Canada and North America in the coming months.

A central component of successful class struggles for living wages rolling back the obscene income distributions of neoliberalism will be union organizing. The Bullet publishes here two articles addressing the issue of living wages in terms of organizing in the hotel and retail sectors, and the recent press release of the CLC supporting the federal minimum wage struggle.

Hotel Workers Lead the Struggle

to ‘Upgrade’ the Service Economy

Sedef Arat-Koc, Aparna Sundar and Bryan Evans

In the years preceding and immediately following the Second World War, the trade union movement served to transform work and life for industrial workers and their communities by creating the means to bargain for better wages and working conditions. Now, in the first decade of the 21st century, North American hotel workers are engaged in a key struggle to transform the quality of work and life in the service economy.

The hotel workers are represented by UNITE-HERE which launched the ‘Hotel Workers Rising’ campaign in December 2005 with the active and very public support of actor Danny Glover who linked the necessity for supporting the struggles of low wage workers. And it is more than low wages at the centre of this struggle. The intersection of race and class in the hotel industry is anything but ambiguous. The higher-end front-line positions which also allow for career progress are invariably staffed by white workers. The back-room, largely dead-end positions are reserved for black workers and immigrants. The statistics make clear the racialization of hotel work where fully seventy per cent (70%) of hotel workers are immigrants and fifty-two per cent (52%) are visible minority. The median wage for Toronto hotel workers – union and non-union – is $26,000 per year. Not exactly a princely sum in one of Canada’s most expensive cities. Median hourly wages run from $10.48 to $11.22, depending on the type of job. The union factor is significant as unionized workers average $14/hour – a differential approaching 40 per cent!! Working conditions are a 21st century Dickens tale characterized by intensification of work, a lack of job control and consequently, soaring injury rates. Musculo-skeletal Disorders (MSD’s) are amongst the highest in any industrial sector as a result of the volume of heavy lifting required especially among hotel housekeepers. In one massive study of 40,000 hotel employees found that injury rates were increasing as hotels added heavier beds and room amenities such as treadmills.

The Hotel Workers Rising campaign is creative and enthusiastic. Its actions and events are heavily attended by not only hotel workers but their families and community allies. It isn’t so much a campaign as a social movement which looks and feels like it not only central but on the winning side of change. And it is! This success is no doubt in part the result of the campaign vision and strategy to link these industry issues to larger questions of what kind of quality of life, what kind of society and economy do we want to have in Canada and in North America? Hotel Workers Rising explicitly links their efforts to the

Toronto Labour Council’s Million Reasons to Take Action campaign which seeks to mobilize around the damning fact that one million workers in the greater Toronto area earn less than $30,000/ year. Again, the racialized dimension in these numbers cannot be lost as many of these underpaid and undervalued workers are people of colour and new Canadians. The Labour Council’s campaign ask, as does Hotel Workers Rising – are we willing to leave these people behind and if so what kind of society will we have built. The lesson of these campaigns is honest and true – when workers and their families can lift themselves out of poverty, then they and their communities become better places to live.

The battle Hotel Workers Rising has chosen to fight is nothing less than a direct and open challenge to the practices of neoliberal restructuring and the logic of global hyper-competition. In the hotel sector, the forces of globalization have forced a rationalization within the hotel industry which is increasingly populated by a handful of multinational chains – Hilton, Starwood (Sheraton, Four Points, Westin, and Le Meridian), Marriott, Fairmont (Delta), Intercontinental (Crown Plaza, Holiday Inns) to name the more prominent ones. The hotel sector, as with the service sector generally, confronted by the issue of productivity. It requires human labour and skill. Technology can do little to extract more profit in this sector. Instead, profit can only be increased the old fashioned way – through extreme exploitation of labour. And hence, the macro political problem the hotel workers and UNITE-HERE have chosen to take on: how to better distribute that profit, as a beginning basis to increase workers’ power beyond profits. It’s not an abstract problem.

Between 1981 and 2001 the poverty rate for immigrants in Toronto increased by 125%. So much for a rising tide lifting all boats! The 1990s were a decade if decline and stagnation for most Canadians. The worst since the Great Depression. In that bitter decade incomes of two-parent families dropped 13% in real dollars. The plight of single-parent families was, of course, worse. Their incomes dropped 18%. As of 2005, 35.1% of Toronto’s children lived in poverty. A disgusting fact given that the economy has never been more robust in creating wealth. In 2004, corporate profits reached a all-time, historic high composing 14% of the Canadian GDP. And all this while our modest welfare state continues to shrink and restrict benefits. For example only 26 per cent of Toronto’s jobless are even eligible for Employment Insurance. Again, this speaks volumes as to the importance of the hotel workers campaign to lift living standards throughout the service economy.

To advance the ‘high road’ vision of the campaign, UNITE-HERE has taken over the past months 14 strike votes in Toronto area hotels and garnered an astonishing 98% strike vote. The strategy has been to set in motion co-ordinated sector-based bargaining. Victories have been achieved at the Downtown and airport Hilton and at the Sheraton Centre. The Delta Chelsea Hotel however is attempting to break the pattern being set by the union and have drawn a line. In particular, Delta Chelsea management is actively courting owners of some 25 new hotel projects now in the planning stage for Toronto to stop the union’s progress at the bargaining table. Other unions which frequently do business with the Delta Chelsea – notably the Ontario Public Service Employees Union, the Canadian Union of Public Employees, and the Power Workers Union (Ontario hydro) are currently boycotting the Delta and have cancelled a number of contracts with that hotel.

This workers’ movement harkens back to the great struggles of the Committee of Industrial Organizations which grew through the 1930s and 1940s. A movement which transformed the lives of workers and the communities in which they lived. The Hotel Workers Rising campaign has the potential to do the same, to transform our times – a trade union movement for the 21st Century, if you will. •

Challenging Wal-Mart

by Herman Rosenfeld

Raising the minimum wage and increasing the level of social assistance is a component part of challenging the large, low-wage multinationals that make up the vast majority employers of the working poor. The largest of them all is Wal-Mart.

For socialists, Wal-Mart is more than just a series of big retail stores that threaten our communities, bringing an orgy of consumerism and traffic jams. The discount retailer represents, in the words of American social scientist/historian Nelson Lichtenstein, “the template business, setting the standards for a new stage in the history of world capitalism…. It stands for a new set of technological advances, organizational structures and social relationships.”

How does a series of retail stores, play the kind of role in today’s society, that Microsoft, General Motors, U.S. Steel and the railroad monopolies played in earlier epochs?

Wal-Mart is huge. In 2004, its yearly revenues represented 2.3% of the total economic activity of the United States. It also did 20% of the retail toy business and 14% of all grocery sales in that country. Its yearly revenues are larger than those of Switzerland. If Wal-Mart was an independent country, its economy would rank 30th in the world, right behind Saudi Arabia.

It is the largest profit-making enterprise in the world. It has sales of over 300 billion dollars a year and it is predicted that Wal-Mart’s annual sales will soon reach 1 trillion dollars. A study by a leading U.S. corporate consultant firm in 2002 argued that one quarter of American productivity gains from 1995-1999 were due to Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart is the world’s largest retailer. By 2003, it had also become the world’s largest grocer.

In Canada, Wal-Mart entered the market in 1994, purchasing 122 stores previously owned by Woolco. Wal-Mart is now the largest retailer here.

Wal-Mart’s size means that it shapes the retail market in the U.S. and many other countries and since the hollowing out of the manufacturing sector, it plays an inordinately influential role in the economy.

Discount Retail Model

Discount retailing is based upon a simple set of principles. Goods are sold at the lowest possible price, with very low mark-ups over the actual cost of production and with an extremely fast rate of turnover. This places enormous pressure to lower costs at every stage: in production, distribution and in the process of retailing. Wal-Mart has perfected these principles.

Retailing had always been cost sensitive, but discount retailers were particularly driven by cost reduction. The discounters emerged after World War 2, offering large selections of cheaper goods, with stores accessible by car, located off suburban highways. In contrast with the older department stores, located in city centres, the discounters used non-skilled, non-union labour, with shopping done on a self-serve basis.

There were huge numbers of discounters during this period and by the 1980’s recession many of these companies had folded. Wal-Mart originated in the Ozark mountains of Arkansas – a very conservative, small town atmosphere in the 1960’s. Rather than attempt a rapid expansion, Wal-Mart perfected its model in the friendly confines of that part of the U.S. and developed a plan for growth across the USA.

In 1987, Wal-Mart was a successful regional retailer. Five years later, it had become the industry leader. Its dominance came from its adoption and application of information technology to the handling of goods and people; its control over suppliers; its strategic approach to growth; its global reach; ruthless labour practices and its ability to benefit from the wave of neoliberal regulatory and cultural changes that occurred during its growth period.

Globalization, Supply-Chain Dominance and Sweatshop Labour

A key component of Wal-Mart’s strength is its dominance over suppliers. This reverses the historical dependence of retailers upon manufacturers.

Wal-Mart is a monopsony in relation to the supply chain – that is, it is the overwhelmingly dominant market for the manufacturers’ products (for many, it is the only retail outlet). It shapes the structure and location of manufacturers, forcing them into the same low-wage, low-cost system as the retailer. It dominates supplier production and logistics. The sweatshop empires of Nike and some of the clothing companies are miniscule compared to Wal-Mart.

Manufacturers have become dependent upon Wal-Mart’s ability to market their goods – and must respond to Wal-Mart’s requirements. Wal-Mart stores are the biggest marketing channel for consumer products in the world and the 20 million customers who shop there on an average day represent a bigger market than could be reached by traditional mass media advertising.

Wal-Mart demands low prices, a “pull” (production of goods in response to a closely monitored system that predicts the likely customer demand) and “just-in-time” delivery of goods. Suppliers must make their production and delivery system “transparent” (which Wal-Mart is able to force on them through the use of electronic forms of data and inventory control). Wal-Mart sets up its own distribution apparatus as well, replacing wholesalers.

Wal-Mart tells suppliers how and where to produce their goods. They are forced to locate overseas, seeking sweatshop labour to meet Wal-Mart cost and delivery requirements. This, in turn, also creates new logistics and transportation systems. It’s no accident that today Wal-Mart imports more goods from China than either the United Kingdom or Russia.

This has both contributed to and resulted from a new spatial division of labour: ‘developed’ countries lose manufacturing, but the role of low-wage retailing and distribution increases. Wal-Mart increases ‘de-industrialisation’ and precarious work. ‘Developing’ countries have sweated manufacturing, exporting to retailers in U.S. and Europe.

Wal-Mart would never have been able to develop this way without the corresponding advent of capitalist globalization and neoliberalism. The ability to move production across borders at will in response to cost signals makes this possible, as does the destruction of the socialist-oriented balanced developmental models that used to exist in China, Vietnam and partially in India.

Working at Wal-Mart

At the centre of the Wal-Mart’s commitment to “everyday low prices” are low wages and a system of labour control. This involves an intrusive hiring process, wage scales that are lower than other big box stores (individually assigned in secret from other workers), arbitrary hours of work (where “full-time” can mean as few as 20 hours), forcing people to work “off the clock” (not paying workers for hours worked), a precarious workforce, intense surveillance in the workplace, rampant gender discrimination and a centrally-controlled anti-union policy.

Managers formulate labour budgets that must be approved from Wal-Mart headquarters in Bentonville. They always run with too few resources, so that there is always pressure to cut labour costs. (Managers are told that Sam Walton always carried around a “beat yesterday” book that keept track of cost cutting improvements on a regular basis).

There are many facets to Wal-Mart’s anti-unionism. There is the company culture which seeks to create a “family type” atmosphere with the paternalistic Sam Walton making sure that workers’ well-being is being looked after; workers are called ‘associates’; an “open door” policy promises a sympathetic hearing of individual concerns; profit sharing, for those above a certain wage scale; daily meetings where cheers are recited and successful products are touted. There is anti-union propaganda in videos and DVD’s, portraying workers’ organizations as parasites that are jealous of Wal-Mart’s success. Finally, there is the repression of potential union drives by management. This, too, takes a number of forms such as close surveillance of the social interactions between workers, swift action by central authorities in Bentonville when there is any danger of union drives, and co-ordinated efforts to smash unionization drives once they are started. In 2005 Wal-Mart closed its Jonquiere, Quebec store, rather than bargain a first North American collective agreement.

Wal-Mart’s size and domination of retail markets help it to influence wages and working conditions and rates of unionization of society in general, as well as the sector. The very threat of Wal-Mart’s entry into grocery retailing has given unionized employers a weapon to use against workers. The largely unsuccessful California grocery workers strike, where 70,000 workers went out for 140 days, was waged against efforts by unionized employers to match Wal-Mart’s labour costs and practises.

Wal-Mart’s Vision

Wal-Mart helps usher in (and reflects) a particular social and political model: Low consumer prices serve a low-wage economy. As Wal-Mart CEO Lee Scott claims, “Low prices give people a raise every time they shop with us”).

It portrays the giant capitalist as a champion of the “little person”, reinforcing people’s identity as consumers (shoppers) and cancelling out people’s class identity. It claims to cater to the particular needs of women as caregivers and as the main shopper in the family (over ½ of which are single parent families in the U.S.), all the while reinforcing the crassest forms of sexism and paternalism.

Wal-Mart can’t be explained without the neoliberal economic and political reforms of the 1970’s and 80’s. The pool of low-wage workers (many of whom are women) and the extra responsibilities facing women made Wal-Mart possible and attractive. Government deregulation of labour markets and the loss of high wage manufacturing jobs also contributed. The rise of consumer culture and Christian conservative values in the U.S. also played a role.

How Do We Challenge Wal-Mart?

The first question to ask is, what should be our goals in challenging the retail giant and what outcomes do we want? Second, we should ask, what are the most effective ways of accomplishing them?

Should we consider trying to close them down? Aside from being totally unrealizable, this option ignores the very real need that ordinary working people have for reasonably-priced consumer goods, available in conveniently-located stores. Wal-Mart has withdrawn from South Korea and Germany, but this isn’t because the people there demanded that they be kept out. They left because, in the German case at least, they couldn’t tolerate the demands of the unionized workers and a larger culture which didn’t place low prices at the apex of society’s values.

Should we consider breaking it up through anti-trust action? This was a solution considered in a recently published article in the U.S. monthly Harpers. An American-type solution, it doesn’t make sense when applied to a retailing giant. After all, it would only increase the competitive pressures on a series of smaller, discount retailers. On the other hand, it might be a way of addressing Wal-Mart’s monopsony power in relation to its suppliers.

A particularly radical approach would argue for nationalizing it and running it as a series of co-operatives. While this would preserve the economies of scale and the application of technology to lower costs, it is certainly utopian in the current context. Such an approach might only work if we were involved in a larger social movement challenging capitalism and its logic.

That leaves us with modifying the Wal-Mart model, accepting the existence of discount, mass retailing, but changing it in a way that radically improves the conditions in supplier and Wal-Mart workplaces, provides for unionization, forces them to source locally and stop the destruction of local communities and environments.

Can Wal-Mart afford it? Just looking at fair wages and benefits, they certainly could. If Wal-Mart spent $3.50 p/h more for wages and benefits for full timers, it would cost $6.5 billion per year – less than 3% of sales. Wal-Mart claims it would wipe out profit or its “price advantage” over competitors. As a recent Wal-Mart ad crowed, “We’d betray our commitment to tens of millions of customers, many of whom struggle to make ends meet”. (Costco pays $16.00 p/h – 65% more than W-M average and 33% more than Sam’s Club. Costco also covers 82% of its U.S. workers with health insurance, while W-M covers only 48% of its workers.)

What Are Some of the Ways to Force Wal-Mart to Change?

Most important is unionizing them. But current attempts are hardly adequate. It’s not that there isn’t a potential base for organizing the retailer. In the last few years there have been some near successful drives, and just recently there was a mass walkout in a Florida store over hours of work.

Wal-Mart will never be unionized by scattered efforts to organize individual stores. Organizing Wal-Mart requires the same kind of strategic approach that the CIO used to organize the key manufacturing sectors during the 1930s and 1940s. Then, the nascent industrial union movement, inspired by radical social and political movements and legitimized by important legislative reforms, succeeded in unionizing much of the unskilled workforce. Unions worked in a coordinated manner, using a variety of elements: mass, direct action; targeting key areas in each industry; salting and working from the outside; community mobilization.

Today, unions in both the USA and Canada need to put aside their narrow institutional interests and make the unionization of Wal-Mart a number one collective priority. Needless to say, in order to pressure Bentonville, such a campaign would requite a fundamental change in the deferential approach that most unions take towards both employers and neoliberal governments. They also would have to work with a number of mass movements that are affected by Wal-Mart, such as the women’s movement, environmentalists, former Wal-Mart workers, health care activists, anti-globalization and anti-sweatshop organizations and movements for local community democracy. (The consequences of not developing such an approach can be seen by the pathetic response of the union movement to the closure of the Jonquiere store. Wal-Mart got the message, loud and clear.)

There is also the proposed Wal-Mart Worker Association model of non-majority unions, proposed by veteran American organizer Wade Rathke. He argues that current conditions don’t allow Wal-Mart unions to become sole bargainers for workers now. Instead, we must build towards that goal, organizing those workers who wish to affiliate to the union movement as part of a bigger series of campaigns, including struggles over workplace rights.

Unions also need to show low wage workers like those at Wal-Mart that they are the most appropriate tools for increasing their living standards and bettering their working conditions. They must challenge two-tier wage models increasingly imposed in the organized retail sector and show why they can provide an alternative to the culture of paternalism that rules places like Wal-Mart.

Political Mobilization is Key

Currently, there are a series of local campaigns to force Wal-Mart to accept certain terms and conditions in order to gain entry to these communities. Local laws affect store size, zoning and location, minimum wages and working conditions, provisions for an impact assessment study, local sourcing and protection of small merchants. Some have successfully limited Wal-Mart, others have kept Wal-Mart out and still others were defeated by Wal-Mart inspired counter campaigns. Hopefully, these campaigns can become part of what clearly needs to be a bigger, multifaceted challenge to Wal-Mart.

As a key leader and beneficiary of both neoliberalism and capitalist globalization it only stands to reason that the giant retailer can only be tamed or reformed as part of a movement against key elements of the latest stage of capitalism. Without a political movement that seeks to limit the mobility of capital, fight free trade and support struggles in developing countries like China for worker rights and alternative development models, it is hard to see how we can succeed in reforming Wal-Mart. In a similar way, the battle against Wal-Mart needs to proceed alongside efforts to establish living wage levels, strengthen labour standards and re-regulate labour markets here at home. •

Herman Rosenfeld is a retired CAW activist living in Toronto.

The Canadian Labour Congress:

Canada Needs a $10/hour Minimum Wage

“Canadians expect that everyone who works should be paid fairly,” says Ken Georgetti, president of the Canadian Labour Congress. “Too many Canadians are working in full time jobs, yet they still have to choose between paying the rent and feeding their families. It’s time to bring back the federal minimum wage to help the growing number of working families earning poverty wages.”

A worker today needs to earn $10.09 per hour for 2,000 hours to reach the poverty line. – Disturbingly, the proportion of adult workers (age 25 plus) who are working for less than these wages has increased in 2006. They are workers who, working full-time hours for the whole year, still would not reach the Statistics Canada low-income line.

“The federal government recently commissioned and paid for its own review of Canada’s labour standards. The report came in last October and it calls for the restoration of a federal minimum wage that would be set at the poverty line as a way to address the growth of precarious, low-wage jobs across the country,” explains Georgetti. (That report is available at www.fls-ntf.gc.ca/en/fin-rpt.asp).

In December, the Canadian Labour Congress’ Report Card 2006 Is Your Work Working for You?, which compares job and income statistics for the first half of each year since 2001, noted a disturbing growth in the number of Canadians unable to earn enough to meet their basic needs in the first part of 2006 despite strong job creation numbers over the same period.

“Getting a job is supposed to mean getting ahead. It’s supposed to be a family’s ticket out of poverty. A country so prosperous and rich in opportunity should be able to do better for working citizens,” concludes Georgetti.

The Canadian Labour Congress’ Report Card 2006 Is Your Work Working for You?, is available at www.working4you.ca.

The Canadian Labour Congress, the national voice of the labour movement, represents 3.2 million Canadian workers. The CLC brings together Canada’s national and international unions along with the provincial and territorial federations of labour and 135 district labour councils.

Web site: www.canadianlabour.ca