Conservatives: Overestimating their Popularity

“For a Germany in which we live well and happily.” Maybe it was just this less than catchy campaign slogan that cost Angela Merkel’s conservative CDU so dearly at the polls; leaving the party at a record low of 26.8 per cent of the total vote. What is more likely, though, is that the slogan was better at revealing chancellor Merkel’s state of mind – something like: A Germany that should be happy that I govern it so well – than capturing the mood of many of her erstwhile supporters. The conservatives had little sense that terrorism and refugee hysteria were much more than media spectacles. The hysteria indicates how much the so-glad-it’s-not-as-bad-as-elsewhere mood that helped to elect Merkel in the aftermath of the Great Recession and after the Euro-crisis had given way to a much more pessimistic zeitgeist. Locked into the corridors of power, Merkel and her party underestimated the shift from positive to negative outlooks amongst significant parts of the electorate.

Social Democrats:

Stumbling over the equity-employment trade off

The Social Democratic Party (SPD) failed doing the splits. One foot, notably at the beginning of Martin Schulze’s campaign, moved toward genuine social democratic policies. The reward: A massive surge in the polls and party membership. Yet, while the campaign went on, the other foot moved toward the embrace of the social counter-reforms that, in the early 2000s, former chancellor Gerhard Schröder forced through party and parliament at the cost of losing the left wing of the SPD, which merged with the then existing Party of Democratic Socialism into Die Linke. For years, corporate media and Merkel praised the Schröder-cuts as trigger of an employment boom. In fact, Merkel won the last two elections resolutely by propagating the view that Germany had found the magic formula to prosperity while the rest of the world went bust. Crediting Schröder rather than herself as originator of this formula gave her an aura of modesty in a political world mostly inhabited by bullies and big mouths. And, of course, it was a constant reminder to social democratic supporters, who are usually more concerned with social justice than conservatives, that it was ‘their’ chancellor who cut the German welfare state to size.

| Vote share in % | Change in % from 2013 election |

|

|---|---|---|

| CDU | 26.8 | -7.4 |

| CSU | 6.2 | -1.2 |

| SPD | 20.5 | -5.2 |

| Die Linke | 9.2 | 0.6 |

| Greens | 8.9 | 0.5 |

| FDP | 10.7 | 6.0 |

| AfD | 12.6 | 7.9 |

| The Bavarian CSU (Christian Social Union) and the CDU (Christian Democratic Union) in the rest of the country form a joint conservative caucus in the federal parliament. SPD – Social Democratic Party of Germany, FDP – Free Democratic Party (liberal), AfD – Alternative for Germany (far right). [German federal election, 2017] |

||

The SPD tried twice to cash in on their alleged role in boosting employment. They failed twice and decided to have it both ways this time: Advocating social justice and taking credit for advancing employment at the price of escalating inequality. Voters, proving that they are much smarter than politicians usually think they are, figured that this was a contradicto in adjecto. Some among them may also have had doubts whether a trade off between equality and employment exists in the first place. Whatever issues voters had with the SPD, their electoral results went from bad to worse, reaching, like the CDU, an all-time low of 20.5 per cent.

Die Linke: Unable to capitalize on widespread tastes for welfare state policies

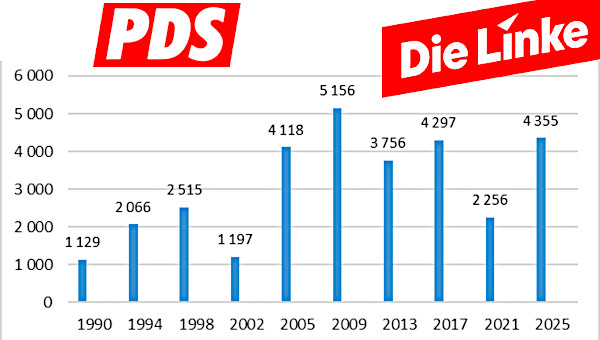

Die Linke is puzzling. Founded as a merger of left-wing social democrats who defected from Schröder’s Third Way SPD and the PDS, which came out of East Germany’s former ruling Socialist Unity Party, Die Linke had social justice written on its birth certificate. It furthers constant debate around the question how social justice could be realized in a world of class struggle from above and economic stagnation. These debates deliver a plethora of facts and arguments to hammer out election campaigns. One of its frontrunners, Sarah Wagenknecht, routinely deconstructed neoliberal mythologies about the welfare state and union triggered crises and developed alternative policies out of the rubble of these mythologies. This ability made her something like a media darling. But neither Wagenknecht’s media presence nor the endless hours party activists spent on the campaign trail helped to translate the widespread taste for social justice, time and again revealed in opinion polls, into rising support for Die Linke.

When the SPD candidate Schulz hinted at a social democratic turn early in his campaign, SPD ratings shot up. When these hints turned out as fake news, SPD ratings collapsed but it still wasn’t Die Linke that benefited from the widespread taste for social democratic policies that the SPD couldn’t satisfy. Compared to the last elections, Die Linke’s share of the total vote improved by a meagre 0.9% to 9.2 per cent.

The Greens: From greening the old left to elitist lifestyle policies

The Greens share Die Linke’s inability to capitalize on widespread discontent. However, the difference between the two is that Die Linke aims at turning discontent with economic and social conditions into a social force that could change these conditions. The Greens, once a vanguard of greening old left agendas, would be content to attract voters from governing parties to increase their electoral market share within largely unchanged conditions. As a social force, they mostly represent a saturated middle class engaging in greened conspicuous consumption to distinguish itself from the cheap-deal chasing classes. Locked into self-chosen exclusivity, they have a hard time gaining shares in mass democratic voter markets. But this doesn’t mean that they are locked out from the corridors of power. At the time of writing, it seems that 8.9% of the total vote suffice as entry ticket to a coalition government with the conservatives and the liberal FDP.

The Greens emerged at the tail end of the rebellious 1970s as an attempt to transform the still existing zeal of the new social movements into an institutional presence against the rising tide of neoliberalism. The new social movements, to be sure, were triggered by insufficiencies of the old left. Tragically, efforts to green the old red agenda failed inside the movements and the Green party also. This opened the door for their transformation into a rather elitist middle-class party. A position it shares with the liberal FDP.

Liberals: Organize opportunism embraces economic nationalism

After WWII, this party of organized opportunism gave democratic cover to some old Nazis, though most of them joined the conservatives, and free traders. This strange mix was only possible under Cold War conditions. When policies of détente softened these conditions and the 68 rebellion signalled the coming of a new world, the FDP shed its Nazis and reinvented itself as a party of social liberalism and became a coalition partner of the SPD in the late 1960s. In the 1950s and into the early 1960s, the still Nazi-enriched liberals had been loyal to the equally Nazi-staffed conservatives. The late 1960s social liberal incarnation of the FDP didn’t last long; it had barely begun when a combination of economic crises and various social movements represented a double threat to profit rates. Under those conditions, the social democratic left failed to forge a bloc with unions and other social movements that would have pushed the entire party from the post-WWII class compromise to a socialist reformism consciously deepening the crisis of profitability to further socialist transformation. Yet, efforts to do so were enough for the liberals to renew their alliance with the conservatives. Being a catchall party with support from farmers, the petty bourgeoisie and even layers of the working class, the conservatives were slow and hesitant to embrace the neoliberal creed capitalists adopted in response to the crisis of profitability.

The liberals with a smaller support base less reliant on the social layers supporting the conservatives became the vanguard of neoliberalism in Germany. They were so true to their principles that eventually many of its long-time supporters realized that they had long denied stakes in the welfare state and that future doses of neoliberal policies might kill these stakes. As a result, the FDP failed to pass the 5% mark necessary to gain seats in parliament in the 2013 elections but, scoring 10.7% of the vote, had quite a comeback this time around. The liberals had refined their neoliberal commitments, inextricably linked to free trade in the past, by calling upon the state to secure the gains from international economic activity for German citizens. In a time of economic instability and stagnation where even many middle-class people fear they might fall behind, this economic nationalism has more voter appeal than the unrepentant free trade commitments of the pre-Great Recession and pre-Euro-crisis years.

Far right AfD:

Neoliberalism wrapped in Deutschland über alles

Even more successful than liberals at rebranding as economic nationalists was the far right AfD by wrapping its programmatic commitment to neoliberal counter-reforms into thick layers of racism, Islamophobia and, more recently, anti-Semitism supplemented with praise for Germany’s Nazi-past. This brew allowed the AfD to increase its vote share by 7.9%, a little more than the losses suffered by the conservatives, to 12.6 per cent. All other parties campaigned in an ideological field demarcated by neoliberal economics, by conjuring up its past glory, like the conservatives, amending it with touches of social justice, green or assertive foreign policies, like the social democrats, Greens and liberals respectively, or by advocating for the transformation of the neoliberal order into a new kind of welfare state or even a socialist order, like Die Linke. The AfD abandoned the economic field entirely and moved on to politically greener, or maybe browner, fields of race and nation. In a softer version these are presented as culturally inherited identities, in a hard-core version they are biologically determined. Deutschland über alles is the key message in both versions.

Fear Takes Centre Stage

All other parties consider the AfD as a threat to democracy and social cohesion in Germany. To be sure, most parts of the Bavarian CSU and parts of the CDU understand this threat as some other party, the AfD, occupying an ideological field they had reserved for themselves in the past even though they made less noise about it than the AfD. Apart from this qualification, the shock about the AfD’s rise is genuine but pretty helpless, too. Expressions of this shock adopt the far right agenda so that the AfD’s preferred scapegoats – refugees – have taken centre stage in political discourse while they are marginalized economically and socially. Other parties don’t share the AfD’s message, at least not as blatantly as the AfD puts it forward. They may even oppose it. But by focusing so much on refugees they contribute to the shift in discourse from economics to race and nation. Sure enough, many people who feel the pinch of economic insecurity see refugees as unwanted competitors for jobs or welfare provisions. This economic rationale would actually be open to debates seeking policies to reconcile domestic concerns about job and income security with refugee concerns about – exactly the same issues. This is what Die Linke tried. Occasionally, Wagenknecht added a dose of anti-refugee sentiment to her economic messaging while other parts of the party came to a moral defense of refugees that put the left classic argument that capitalism is based on a scarcity of jobs on hold as far as refugees were concerned. For most parts of the election campaign, though, Die Linke managed to present refugees as a particularly vulnerable part of a working class undergoing massive transformations.

The recomposition of the working class in Germany, as elsewhere, certainly has something to do with the influx of refugees and immigrants. But it also has to do, in quantitative terms probably more so, with outsourcing, privatizations, relocation of operations and automation. Combined with pressures on wages, the lowering of social standards and public service cuts this recomposition leads to massive insecurities. They are particularly hard felt, though to different degree by different layers of the working class, because long established forms of representation, through unions, parties, civil society organization and the media were thrown into crises by waves of economic restructuring. A decline of membership in unions and civil society organizations, increasing volatility in the electoral system, most recently illustrated by the fall and rebound of the FDP and the rise of the AfD, and the social media spectacle testify to this crisis of representation. This crisis renders frames through which workers and layers of the middle class could make sense of their respective economic and social conditions obsolete. As a result, objectively existing and increasing insecurities are perceived as unintelligible threats. Fear reigns supreme and eclipses reason. The new German angst is projected onto refugees and immigrants. Arriving at a time of present-day insecurities and dismal outlooks onto the future, foreigners who run for their lives or look for a brighter future unleash the ghosts of history amongst wide swaths of the German population. The conservatives were still living in the recent past when Germany looked like an island of stability in a sea of economic turmoil. Pointing at high levels of employment and balanced budgets, they were quiet about increasing inequalities and insecurities. Yet, these are important concerns for growing numbers of people.

Tragically, thinking about economic and social issues is still dominated by the neoliberal imperatives of competitiveness, deregulation and balanced budgets. Alternative ways of economic thinking that can explain growing inequality and insecurity as outcomes of neoliberal policies, thereby articulate growing discontents and rally for policy alternatives, remain in the shadow of the neoliberal populism that dominates public debates for decades. Die Linke tried hard to strike a different economic chord but it either wasn’t heard or didn’t resonate. Economic reasoning and neoliberalism, even if, or maybe because, it is more of a religion than reasoning, are widely seen as one and the same. This is not only true for 99% of economic professors, 90% of politicians but also the vast majority of the population. Consequently, people finding themselves at the losing end of neoliberalism often express their discontent in non-economic terms. That’s why the AfD’s wrapping their own brand of neoliberalism in a diversity of chauvinistic identity covers was so successful. Finding a different economic language that the discontented can understand and clearly distinguish from the neoliberal creed is possibly the key challenge for Die Linke and the left outside the party to counter the pull to the right that currently dominates politics in Germany. •