Scapegoating Politics: How Fascism Deploys Race, and How Antiracism Takes the Bait

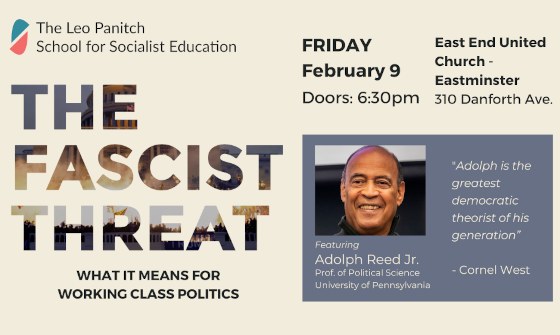

Adolph Reed will be speaking in Toronto on February 9th, The Fascist Threat and What it Means for Working Class Politics.

In 2022 and early 2023, a highly publicized petition campaign sought to recall New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell. Louisiana law sets high hurdles for recall initiatives; in a jurisdiction the size of New Orleans, triggering the process requires valid signatures from twenty percent of registered voters on a petition requesting a recall election, and the effort ultimately failed. Nevertheless, the campaign is worth reflecting on for three reasons.

First, it at least bears a strong family resemblance to right-wing Republican attacks on Democrat-governed cities that recently have escalated from inflammatory rhetoric to concerted attempts to disempower, by extraordinary means, jurisdictions Democrats represent. To that extent, the Cantrell recall campaign is of a piece with the many Republican efforts at voter suppression around the country and the right’s broader and more openly authoritarian assault on democratic institutions at every level of government about which Thomas Byrne Edsall sounded the alarm in the New York Times.1

Second, the NOLATOYA campaign illustrates how race can function as a condensation symbol, a shorthand, diffuse, even tacit component of a discourse of political mobilization while not necessarily defining the mobilization’s policy objectives. Third, the character of the campaign, especially in light of the larger tendency of which it may be an instance, and the opposition’s responses also demonstrate the inadequacy of race-reductionist understandings even of the racialist element that helped drive it and the other reactionary initiatives, such as the Mississippi legislature’s move to undercut the authority of Jackson’s elected government.

The Recall Campaign

The recall’s sponsors sought to stoke and take advantage of anxieties about street crime – most conspicuously the waves of porch piracy, carjackings, and homicides that spiked in New Orleans as in many cities during and after the Coronavirus pandemic and lockdown – as well as the prodigiously bad, borderline dangerous condition of municipal roads and streets, a seemingly inexplicable and chronically unresolved breakdown of the city’s privatized sanitation pick-up operation, and the at best inconsistent quality of other public services.2 The campaign also played on hoary, racially inflected tropes such as generic allegations of incompetence and evocations of charges of immoral and “uppity” behavior, for example, in attacks on Cantrell for allegedly having an affair with a police officer on her detail, living at least part-time in a municipally owned luxury apartment on Jackson Square in the heart of the Vieux Carré, and flying first class at the city’s expense on international trade junkets.3 Recall supporters eventually leveled inflammatory allegations of incompetence, hostility to law enforcement, or corruption against the black, recently elected Orleans Parish District Attorney and unspecified judges and suggested that subsequent recall initiatives should target them as well.

The campaign’s titular co-chairs were black: one, Belden “Noonie Man” Batiste, was a perennial candidate for electoral office who received five percent of the vote in the 2021 mayoral primary that Cantrell won with nearly sixty-five percent; the other, Eileen Carter, is a freelance “strategy consultant” who had been a first-term Cantrell administration appointee.4 Its sources of financial backing remained shadowy for months, but disclosures eventually confirmed that more than ninety percent of the campaign’s funding came from a single white developer and hospitality industry operative, Richard Farrell, who, in addition to having contributed to Cantrell in the past, had been one of Louisiana’s largest donors to the 2020 Trump presidential campaign.5 Opponents of the recall argued that the fact that the initiative was funded almost entirely by a Trump mega-donor and its organizers’ attempt to purge the voter rolls in order to reduce the total number of signatures needed to force a new election6 indicated a more insidious objective, that the campaign was a ploy to advance the Republicans’ broader agenda of suppressing black voting and to discredit black officials.7

After much hype, the campaign failed abysmally. Certification of the petitions confirmed both that organizers had fallen far short of the minimum signature threshold required to spur a recall election and that support was sharply skewed racially. The latter was no surprise.8 The campaign originated in one of the wealthiest, whitest, and most Republican-leaning neighborhoods in the city. And, as I have indicated, proponents’ rhetoric – notwithstanding their insistence that the initiative had broad support across the city – traded in racialized imagery of feral criminality, and it too easily veered toward hyperbolic denunciation of the mayor’s purported moral degeneracy and an animus that seemed far out of proportion to her actual or alleged transgressions, which in any event hardly seemed to warrant the extraordinary effort of a recall, especially because Cantrell was term-limited and ineligible to pursue re-election in 2025. The extent to which recall advocates’ demonization of her drifted over into attacks on other black public officials also suggested a racial dimension to the campaign that no doubt made many black voters wary.

A racial explanation of the recall initiative offers benefits of familiarity. It fits into well-worn grooves of racial interest-group politics on both sides. It permits committed supporters of the recall to dismiss their effort’s failure as the result of blacks’ irresponsible racial-group defensiveness to the point of fraudulence and conspiracy, and it enables opponents to dismiss grievances against Cantrell’s mayoralty by attributing them to an effectively primordial white racism linked via historical allegory to the Jim Crow era.9 So, when journalists Jeff Adelson and Matt Sledge estimated that, although fifty-four percent of registered voters in Orleans Parish are black and thirty-six percent are white, seventy-six percent of the petition’s signers were white and just over fifteen percent were black, the finding was easily assimilable to a conventional “blacks say tomayto/whites say tomahto” racial narrative. The authors’ punchy inference that “White voters were more than seven times more likely to have signed the petition than a Black voter” reinforces that view.

By Adelson and Sledge’s calculation, more than 23,000 white voters signed the recall petition compared with roughly 7,000 blacks. At first blush, that stark difference seems to support a racial interpretation of the initiative. Yet that calculation also means that more than 57,000 white voters, for whatever reasons, did not sign it. That is, roughly two and a half times more white Orleans Parish voters did not sign the recall petition than did. One might wonder, therefore, why we should see support for the recall as the “white” position. Signers clustered disproportionately in the most affluent areas citywide, and those least likely to sign were concentrated in the city’s poorest areas. As Adelson and Sledge also note, there are many reasons one might not have signed the petition. Those could have ranged from explicit opposition to the initiative; skepticism about its motives, likelihood of success, or its impact if successful; absence of sufficient concern with the issue to seek to sign on; or other reasons entirely. That range would apply to the seventy percent of white voters who did not sign as well as the nearly ninety-five percent of black voters who did not. From that perspective, “race” is in this instance less an explanation than an alternative to one.

Organizers and supporters of the recall no doubt also had various motives and objectives, and those may have evolved with the campaign itself. Batiste and Carter are political opportunists and, as a badly defeated opponent and a former staffer, may harbor idiosyncratic personal grievances against Cantrell; they also cannot be reduced merely to race traitors or dupes not least because roughly 7,000 more black voters signed onto the recall petition. Farrell and the handful of other Republican large donors who sustained the initiative likely had varying long- and short-game objectives, from weakening Cantrell’s mayoralty to payback for the city’s aggressive pandemic response, which met with disgruntlement and opposition from hospitality industry operators, to fomenting demoralization and antagonism toward municipal government or government in general, to enhancing individual and organizational leverage in mundane partisan politics, including simply reinforcing the knee-jerk partisan divide. And, even if not in the minds of initiators all along, voter suppression in Orleans Parish may have become an unanticipated benefit along the way.

Other enthusiasts no doubt acted from a mélange of motives. Demands for “accountability” and “transparency,” neoliberal shibboleths that only seem to convey specific meanings, stood in for causal arguments tying conditions in the city that have generated frustration, anxiety, or fear to claims about Cantrell’s character. Those Orwellian catchwords of a larger program of de-democratization10 overlap the often allusively racialized discourse in which Cantrell, black officialdom, unresponsive, purportedly inept and corrupt government, uncontrolled criminality, and intensifying insecurity and social breakdown all signify one another as a singular, though amorphous, target of resentment. The recall campaign condensed frustrations and anxieties into a politics of scapegoating that fixates all those vague or inchoate concerns onto a malevolent, alien entity that exists to thwart or destroy an equally vague and fluid “us.” And that entity is partly racialized because race is a discourse of scapegoating.

But race is not the only basis for scapegoating. As I indicate elsewhere, “the MAGA fantasy of ‘the pedophile Democratic elite’ today provides a scapegoat no one might reasonably defend and thus facilitates the misdirection that is always central to a politics of scapegoating, construction of the fantasy of the ‘Jew/Jew-Bolshevik-Jew banker’ and cosmopolite/Jew and Jew/Slav subhuman did the same for Hitler’s National Socialism.”11 The scapegoat is an evanescent presence, created through moral panic and just-so stories and projected onto targeted individuals or populations posited as the embodied cause of the conditions generating fear and anxiety. As an instrument of political action, scapegoating’s objective is to fashion a large popular constituency defined by perceived threat from and opposition to a demonized other, a constituency that then can be mobilized against policies and political agendas activists identify with the evil other and its nefarious designs – without having to address those policies and agendas on their merits.

A Facebook post a colleague shared from a relative long since lost to the QAnon/MAGA world exemplifies the chain of associations undergirding that strain of conspiratorial thinking and its scapegoating politics: “It’s time for Americans to stop hiding behind the democracy dupe that has been used as an opiate to extort American wages to wage war against any country that said no to Rothschild’s money changing loanshark wannabe satan’s cult.” My colleague underscored that the antisemitism apparent in that post was a late-life graft onto the relative’s political views; neither Jews nor Jewishness had any presence in the circumstances of their upbringing, neither within their family nor the broader demographic environment. Antisemitism, that is, can function, at least for a time, as an item on a checklist that signals belonging in the elect of combatants against the malevolent grand conspiracy as much as or more than it expresses a committed bigotry against Jews or Judaism.

It is understandable that the partly racialized recall campaign would provoke a least-common-denominator objection that it was a ploy to attack black, or black female, political leadership. It no doubt was, at least as an easy first pass at low-hanging fruit in mobilizing support. However, complaint that the recall effort was racially motivated missed the point – or took the bait. Scapegoating is fundamentally about misdirection, like a pickpocket’s dodge. A politics based on scapegoating is especially attractive to proponents of anti-popular, inegalitarian agendas who might otherwise be unable to elicit broad support for programs and initiatives that are anti-democratic or facilitate regressive redistribution.12 And the forces driving the Cantrell recall campaign fit that profile.

That it was backed by significant right-wing donors yet failed so badly raises a possibility that the recall campaign may never have been serious as an attempt to remove Cantrell from office.13 If their prattle about accountability, transparency, and responsibility to taxpayers were genuine, organizers should have admitted the failure and not bothered to submit their petitions and thereby avoided the administrative burdens of the certification process – unless forcing that extraordinary undertaking were part of a Potemkin effort to simulate a serious recall campaign. Instead, well after it should have recognized and acknowledged failure, the campaign organization attempted to keep recall chatter in the news cycle by means of coyness and dissimulation regarding the status of their effort and continued to manufacture supposed Cantrell outrages, no matter how dubious or picayune, to feed the fires of salacious exposé of the “you won’t believe what she’s doing now!” variety. When authorities confirmed the magnitude of the failure, including evidence of thousands of obviously bogus signatures nonetheless submitted, organizers fell back on the standard MAGA-era canard in the face of defeat – challenging the credibility of the officials designated by law to determine the signatures’ validity. Notwithstanding the complex motives and expectations of individual supporters, all this further suggests that the recall initiative at one level was suspiciously consistent with the multifarious assaults on democratic government that right-wing militants have been pursuing concertedly around the country since at least 2020.

That larger, more insidious effort and its objectives – which boil down to elimination of avenues for expression of popular democratic oversight in service to consolidation of unmediated capitalist class power14 – constitute the gravest danger that confronts us. And centering on the racial dimension of stratagems like the Cantrell recall plays into the hands of the architects of that agenda and the scapegoating politics on which they depend by focusing exclusively on an aspect of the tactic and not the goal. From the perspective of that greater danger, whether the recall effort was motivated by racism is quite beside the point. The same applies to any of the many other racially inflected, de-democratizing initiatives the right wing has been pushing. With or without conscious intent, and no matter what shockingly ugly and frightening expressions it may take rhetorically, the racial dimension of the right wing’s not-so-stealth offensive is a smokescreen. The pedophile cannibals, predatory transgender subversives, and proponents of abortion on demand up to birth join familiar significations attached to blacks and a generically threatening nonwhite other in melding a singular, interchangeable, even contradictory – the Jew as banker and Bolshevik – phantasmagorical enemy.

Race Reductionism

An important takeaway from the nature of this threat is that a race-first politics is not capable of responding effectively to it. Race reductionism fails intellectually and is counterproductive politically because its assumption that race/racism is transhistorical and its corresponding demand that we understand the connection between race and politics in contemporary life through analogy with the segregation era or slavery do not equip us to grasp the specificities of the current moment, including the historically specific dangers that face us. This is not a new limitation. That anachronistic orientation underwrote badly inaccurate prognostications about the likely political impact of changing racial demography in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and was totally ineffective for mounting challenges to charterization of the Orleans Parish school system and the destruction of public housing in the midst of the city’s greatest shortage of affordable housing.15 Race-reductionist interpretation could specify neither the mechanisms nor the concatenation of political forces that impelled either of those regressive programs. Race reductionists seemed to assume that defining those interventions, as well as the regressive real estate practices commonly known as gentrification and the problems of hyper-policing, as racist would call forth some sort of remedial response.16 It did not.

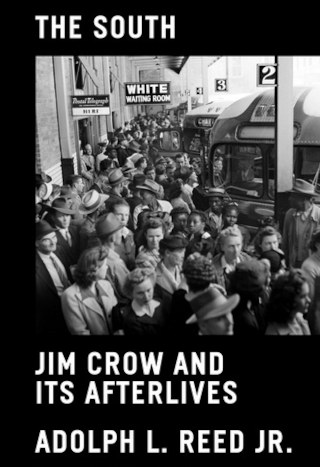

Similarly, just as assertion that mass incarceration is the “New Jim Crow” does not help us understand or respond to the complex political-economic or ideological forces that have produced mass incarceration,17 criticism of contemporary voter suppression efforts by tying them to those at the end of the nineteenth century does not help us specify the nature of the threat, the objectives to which it is linked, or approaches to countering it. Regarding voter suppression and disfranchisement, even in the late nineteenth century, while a) its point was openly and explicitly to disfranchise blacks and b) there is little reason to doubt the sincerity of the commitments to white supremacy expressed by disfranchisement’s architects, disfranchising blacks for the sake of doing so was not the point either; neither was imposing codified racial subordination an end in itself.

The racial dimension of the reactionary campaign then was also a smokescreen that helped to facilitate assertion of ruling class power after the defeat of the Populist insurgency by attacking blacks as a scapegoat, a misdirection from the Democrat planter-merchant-capitalist elites’ sharply class-skewed agenda, including codified racial segregation, which they could not fully impose until the electorate had been “purified.” From the architects’ perspective, the problem with blacks’ voting was ultimately that they did not reliably vote Democrat. If black voters could have been counted on to vote for the Democrat agenda, committed white supremacy likely would have found expression in areas other than suffrage. Indeed, one facet of Bookerite accommodationist politics at the time – articulated by, among others, novelist Sutton Griggs – was that black Americans’ reflexive support of Republicans had forced Democrats to resort to disfranchisement and that, if principled Democrats felt they could count on black votes, they wouldn’t need to pursue such measures.18 Among advocates of voter suppression today, black voting is in part a metonym for a composite scapegoat that includes Democratic or “liberal” or “woke” voters, all of whom, like the liberal pedophile cannibals, are characterizable as not “real Americans” and whose voting is therefore fraudulent by definition. And propagandists meld the images together in service of deflecting attention from the right’s regressive policy agenda.19

It is instructive that at the same time contemporary rightists commonly tout evidence of support from blacks and Hispanics. Of course, that move is largely a cynical ploy – the lie, straight from the fascist agitator’s handbook, accompanied by a knowing wink to the faithful – to deflect criticism of their obvious racial scapegoating. However, knee-jerk dismissals of that reaction as disingenuous or of black and Hispanic supporters as inauthentic, dupes, or sellouts are problematic. There is certainly no shortage of malicious racism within the right wing, but black and Latino supporters of right-wing politics cannot all be dismissed as the equivalent of cash-and-carry minstrel hustlers like Diamond & Silk or cash-and-carry lunatics like Ben Carson and Clarence Thomas, just as the 7,000 blacks who signed the Cantrell recall petition cannot be dismissed as dupes of the NOLATOYA campaigners. While the percentages remained relatively small, increases in black and Hispanic votes for Trump between 2016 and 2020 indicate that those voters see more in the faux populist appeal than racism or white supremacy.20

What is true of those black and brown voters who are unlikely to see themselves as racists21 is no doubt also true for some percentage of whites who gravitate toward the reactionary right’s siren song.22 I do not mean to suggest that we should pander to the reactionary expressions around which the right has sought to mobilize those people. Nevertheless, I do want to stress that what makes many of them susceptible to that ugly politics is a reasonable sense that Democratic liberalism has offered them little for a half century. Obama promised transcendence and deliverance, based on evanescent imagery deriving largely from his race. His failure to live up to the “hope” he promoted set the stage for an equal and opposite reaction.

Most of all, race-reductionist explanations and simplistic historical analogies are counterproductive as a politics because they fail to provide a basis for challenging the looming authoritarian threat. I have asked supporters of reparations politics for more than twenty years how they imagine forming a political coalition broad enough to prevail on that objective in a majoritarian democracy.23 To date, the question has never received a response other than some version of the non sequitur “don’t you agree that black people deserve compensation?” or sophistries like the flippant assertion that abolition and the civil rights movement did not have a chance to win until they did.24 Recently, a questioner from the audience, someone with whom I have had a running exchange over many years regarding racism’s primacy as a political force, catechized me at a panel at Columbia University [beginning at 1:01:48] for my views on the Mississippi legislature’s attacks on the city of Jackson. There was no specific question; the intervention was a prompt for me to acknowledge that the Jackson case is evidence of racism’s independent power. That interaction captures a crucial problem with race reductionism as a politics. It centers on exposé and moralistic accusation.

But what would happen if we were to accept as common sense the conviction of advocates of race-reductionist politics that “racism” is the source of the various inequalities and injustices that affect us – including the anti-democratic travesties being perpetrated on Jackson’s residents and elected officials? What policy interventions would follow? And how would they be realized? Those questions do not arise because the point of this politics is not to transform social relations but to secure the social position of those who purport to speak on behalf of an undifferentiated black population. Insofar as it is a politics at all, it is an interest-group arrangement in which Racial Spokespersons propound as “racial” perspectives points of view that harmonize with Democratic neoliberalism. For the umpteenth time,25 a politics focused on identifying group-level disparities within the current regime of capitalist inequality is predicated logically, but most of all materially, on not challenging that regime but equalizing “group” differences within it. That anti-disparitarian politics hews to neoliberalism’s egalitarian ideal of equal access to competition for a steadily shrinking pool of opportunities for a secure life.26 And, as has been explicit since at least 2015, when the Bernie Sanders campaign pushed a more social-democratic approach toward the center stage of American political debate, anti-disparitarian “leftism” is a militant ideological force defending neoliberalism’s logic against downwardly redistributive threats, to the extent of denouncing calls for expanding the sphere of universal public goods as irresponsible and castigating appeals to working-class interests as racist.

Decades of race reductionist assertion and resort to history as allegory in lieu of empirical argument and clear political strategy27 have propagated another discourse of misdirection. Insistence that any inequality or injustice affecting black people must be understood as resultant from a generic and transhistorical racism, for instance, shifts attention away from the current sources of inequality in capitalist political economy for reductionist antiracists just as culture war rhetoric does for the right. As the genesis of the “racial wealth gap” has shown, the premise that slavery and Jim Crow continue to shape all black people’s lives and forge a fundamentally common condition of suffering and common destiny has underwritten a racial trickledown policy response that is a class politics dressed up as a racial-group politics.28 The sleight-of-hand that makes capitalist class dynamics disappear into a narrative of unremitting, demonic White Supremacy does the work for Democratic neoliberals, of whatever color or gender, that the pedophile cannibal bugbear does for the reactionary right. Thus race reductionism can present making rich black people richer and narrowing the “wealth gap” between them and their white counterparts as a strategy for pursuit of justice for all black people or attack social-democratic policy proposals as somehow not relevant to blacks and indeed abetting white racists, or attempt to whistle past the fact that the Racial Reckoning produced by the Summer of George Floyd culminated most conspicuously in a $100-million gift from Jeff Bezos to Van Jones and a flood of nearly $2-billion of corporate money into various racial justice advocacy organizations.

The rise of the authoritarian threat should raise the stakes of the moment to a point at which we recognize that this antiracist politics has no agenda for winning significant reforms, much less a strategy for social transformation, that it is not only incapable of anchoring a challenge to the peril that faces us but is fundamentally not interested in doing so. There seems to be a startling myopia underlying this politics and the strata whose interests it articulates – unless, of course, its only point is to secure what Kenneth Warren characterizes as “managerial authority over the nation’s Negro problem,”29 no matter what regime is in power. In that case, the Judenrat is in effect its model, and therefore all bets are off. •

This article first published on the NonSite website.

Adolph Reed will be speaking in Toronto on February 9th, The Fascist Threat and What it Means for Working Class Politics.

Endnotes

- On the extent of Republicans’ general, systematic strategy of immobilizing and delegitimizing Democratic officials and democratic government, see Thomas B. Edsall, “The Republican Strategists Who Have Carefully Planned All of This,” New York Times, April 12, 2023; and Rachel Kleinfeld, “How Political Violence Went Mainstream on the Right,” Politico, November 7, 2022.

- Tyler Bridges, “Campaign to Recall LaToya Cantrell Is Fueled By Social Media; Organizers Face Long Odds,” NOLA.com, September 3, 2022; and Morgan Lentes, “Problems with Trash Pick-ups in New Orleans Continue into New Year,” WDSU News, January 3, 2023.

- Often such tropes take a dog whistle form intended to provide plausible deniability regarding their racial character. In the 1989 New York mayoral race, comedian Jackie Mason left no room for doubt or ambiguity. In expressing his support for Rudolph Giuliani’s initial unsuccessful New York mayoral campaign and attempting to smear his opponent, David Dinkins, as incompetent, Mason infamously described Dinkins as looking “like a black model without a job”; see Howard Kurtz, “Quips Create Political Uproar,” Washington Post, September 28, 1989. Mason also disparaged Dinkins as a “fancy schvartze with a moustache,” and he and other Giuliani supporters attacked Dinkins for his supposed fashion affectations and described him as a “washroom attendant.” Kevin Baker, “David Dinkins: The Right Mayor at the Wrong Time,” Politico, December 26, 2020.

- Anita D. Brown, “Political Analysis: The Recall Fell Short, But What About all the Dust It Kicked Up?,” New Orleans Tribune, March 21, 2023.

- Matt Sledge, “Businessman Rick Farrell Drops Another Half Million on Effort to Recall Mayor LaToya Cantrell,” NOLA.com, March 16, 2023; and Connor Van Ligten, “Majority of Cantrell Recall Campaign Money Came from Notable GOP Donor, Report Says,” WWL-TV, January 31, 2023.

- State law requires valid signatures from a minimum of twenty percent of registered voters in a jurisdiction the size of New Orleans to authorize the recall process; reduction of the number of registered voters would correspondingly reduce the requisite number of valid signatures. See also Travers Mackel, “Recall LaToya Leaders File Lawsuit Against Orleans Registrar of Voters,” WDSU News, February 16, 2023.

- Charles P. Pierce, “Campaign to Recall New Orleans Mayor Turns on Fight Over Voter Rolls,” Esquire, February 28, 2023. Since the failed campaign, Republicans in the state legislature have pushed a bill that would significantly lower the threshold for triggering recall elections across the board; see Annum Sidiqqui, “Louisiana Lawmakers Push Recall Bill to Full House,” WDSU News, April 26, 2023.

- Jeff Adelson and Matt Sledge, “LaToya Cantrell Recall Petitions Show Sharp Divides Across New Orleans by Race, Neighborhood,” NOLA.com, March 10, 2023; and Paul Murphy, ”Cantrell Recall Falls Short by Thousands of Signatures, Governor Says,” WWL-TV, March 21, 2023.

- Pierce quotes Bill Rousselle, a longtime Cantrell advisor (and, incidentally, my high school classmate), who describes the recall as “a voter suppression move straight out of the Jim Crow era … complete with back room deals.” Pierce, “Campaign to Recall.”

- Damien Cahill, The End of Laissez-Faire?: On the Durability of Embedded Neoliberalism (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2015), 106–16, 155–56. Processes of de-democratization have proceeded across capitalist democracies throughout the postwar era, well before the generally recognized beginnings of neoliberalism in the late 1970s and 1980s. Often advanced rhetorically through a language of efficiency, these processes typically posit an artificial separation of politics and economics and seek to remove the latter from popular democratic oversight, rendering it as a sphere for control by experts and purportedly neutral administration. Insulation of government functions from popular interference by transferring them to unelected, often multi-jurisdictional bodies has been a staple of postwar metropolitan politics in the United States. (See, e.g., Timothy Weaver, “Urban Crisis: The Genesis of a Concept,” Urban Studies 54 [2017]: 2039–55; and Timothy Weaver, Blazing the Neoliberal Trail: Urban Political Development in the United States and the United Kingdom [Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016].) Recent scholarship has noted the significance of the emergence after World War II of a simultaneously professionalized and politicized economics profession and its impact on constraining public policy. For example, see Stephanie L. Mudge, Leftism Reinvented: Western Parties from Socialism to Neoliberalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018); Amy Offner, Sorting Out the Mixed Economy: The Rise and Fall of Welfare and Developmental States in the Americas (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021); and Elizabeth Popp Berman, Thinking Like an Economist (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022). Clara Mattei, The Capital Order: How Economists Invented Austerity and Paved the Way to Fascism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022) has argued that the notion that the economy is separate from the political realm and requires management by professional experts took shape in context of open class struggle in revanchist response to material gains workers made in the United Kingdom and Italy during World War I, and the notion of austerity, which was an invention of that process, was a battering ram against workers’ gains in those two states and elsewhere and a key building block of Italian fascism.

- Adolph Reed, Jr., “Remembering Operation Bagration: When the Red Army Decapitated the Nazi Front,” Common Dreams, June 22, 2022.

- See, for example, regarding the MAGA-era reactionaries’ performance of can-you-top-this faux populist outrage in the theater of “culture” and its juxtaposition to the brazen, often vicious ruling-class programmatic agenda they pursue, Jake Johnson, “ Senate Finance Chief: Nothing Unites GOP More than ‘Helping Rich People Cheat on Their Taxes,’” Common Dreams, April 20, 2023; Jacob Bogage and Maria Luisa Paúl, “The Conservative Campaign to Rewrite Child Labor Laws,” Washington Post, April 23, 2023; Tami Luhby, “Republicans Use Debt Ceiling Bill to Push Work Requirements for Millions Receiving Medicaid and Food Stamps,” CNN, April 26, 2023; Timothy Bella, “Texas Bill Would Require Ten Commandments in Public School Classrooms,” Washington Post, April 21, 2023; Mark Wingfield, “Texas Is First Step in National Plan To Install ‘Chaplains’ in Schools Instead of Professional Counselors,” Baptist News Global, April 20, 2023; Charles Homans, “Ad Flap Leaves Bitter Aftertaste for Bud Light and Warning for Big Business,” New York Times, April 25, 2023; and Gordon Lafer, The One Percent Solution: How Corporations Are Remaking America One State at a Time (Ithaca, NY: ILR Press, 2017).

- Matt Sledge and Jeff Adelson, “With Cantrell Recall Count Complete, New Orleans Learns Signers Include Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck,” NOLA.com, March 23, 2023.

- Adolph Reed, Jr., “The Whole Country Is the Reichstag,” nonsite.org (August 2021).

- Adolph Reed, Jr., “The Post-1965 Trajectory of Race, Class, and Urban Politics in the U.S. Reconsidered,” Labor Studies Journal 41 (2016): 260–91.

- See, for example, Adolph Reed, Jr. and Touré F. Reed, “The Evolution of ‘Race’ and Racial Justice Under Neoliberalism,” in Socialist Register 2022: New Polarizations, Old Contradictions, The Crisis of Centrism, ed. Greg Albo, Leo Panitch, and Colin Leys (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2021), 113–34; and Cedric Johnson, After Black Lives Matter: Policing and Anti-Capitalist Struggle (New York: Verso, 2023).

- See Marie Gottschalk: Caught: The Prison State and the Lockdown of American Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016); Marie Gottschalk and Connor Kilpatrick, “It’s Not Just the Drug War: An Interview with Marie Gottschalk,” Jacobin, March 5, 2015; James Forman, Jr., Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2017); and Johnson, After Black Lives Matter.

- Griggs explores the possible benefits of black support for southern Democrats at several points in his pamphlets and his fictions, perhaps most notably in his 1902 novel, The Unfettered, in which the novel’s hero, Dorlan Warthell, is presented as courageous for daring to urge black electoral support for the Democratic party. See Unfettered: A Novel (Nashville, TN: The Orion Publishing Company, 1902) 90, 92. The definitive examination of the disfranchisement at the end of the nineteenth century remains. J. Morgan Kousser, The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880-1910 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974). I discuss this issue in “The Farce This Time: Race Reductionism as Class Mythology, from the Solid South to Neoliberal Antiracism,” in Adolph Reed, Jr. and Kenneth W. Warren, You Can’t Get There From Here: Black Studies, Cultural Politics, and the Evasion of Inequality (New York: Routledge, forthcoming). On Bookerism, its origins, social and economic foundations, and class character, see August Meier, Negro Thought in America, 1880-1915: Racial Ideologies in the Age of Booker T. Washington (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1963); James D. Anderson, The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988); Michael Rudolph West, The Education of Booker T. Washington: American Democracy and the Idea of Race Relations (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006); and Judith Stein, “‘Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others’: The Political Economy of Racism in the United States,” Science & Society 38 (Winter 1974/1975): 422–63 [reprinted in Adolph Reed, Jr. and Kenneth W. Warren, eds., Renewing Black Intellectual History: The Ideological and Material Foundations of African American Thought (New York: Routledge 2009)]. It is worth noting that the call to diversify black partisan allegiances has been a staple of black political conservatives’ electoral program. The principal black support group for Richard M. Nixon’s 1972 re-election campaign was Black Americans for a Responsible Two-Party System, led by former civil rights attorney, Black Power advocate, and National Chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) Floyd McKissick. Coincidentally perhaps, during that period McKissick received a $19-million commitment from the Nixon administration for his Soul City vanity project.

- I suggest how the chain of associations works in Adolph Reed, Jr., “How Serious Is the Authoritarian Threat in the United States? What Can We Do About It?” Common Dreams, November 12, 2022.

- Mara Ostfeld and Michelle Garcia, “Black Men Shift Slightly Toward Trump in Record Numbers, Polls Show,” NBC, November 4, 2020; and Steven Shepard, “New Poll Shows How Trump Surged with Woman and Hispanics – And Lost Anyway,” Politico, June 30, 2021.

- See, for example, Leslie Lopez, “‘I Believe Trump Like I Believed Obama!’ A Case Study of Two Working-Class ‘Latino’ Trump Voters: My Parents,” nonsite.org (November 2016).

- Once again, the best estimate is that between 6.7 and 9.2 million Trump voters in 2016 had voted for Obama in 2012. Geoffrey Skelley, “Just How Many Obama 2012-Trump 2016 Voters Were There?,” Sabato’s Crystal Ball, June 1, 2017.

- Adolph Reed, Jr., “The Case Against Reparations,” The Progressive (December 2000): 15–17; and Adolph Reed, Jr., “’Let Me Go Get My Big White Man’: The Clientelist Foundations of Contemporary Antiracist Politics,” nonsite.org 39 (March 2020).

- On the latter response, see, for example, “The Reparations Debate (Keeanga Yahmatta-Taylor and Adolph Reed, Jr.),” Dissent, June 24, 2019.

- Reed and Reed, “Evolution of ‘Race’”; Adolph Reed, Jr. and Merlin Chowkwanyun, “Race, Class, Crisis: The Discourse of Racial Disparity and its Analytical Discontents,” in Socialist Register 2012: The Crisis and the Left, ed. Leo Panitch, Greg Albo, and Vivek Chibber (London: Merlin Press, 2011), 149–75; Adolph Reed, Jr., “Splendors and Miseries of the Antiracist ‘Left,’” nonsite.org (November 2016); Adolph Reed, Jr., “Black Politics After 2016,” nonsite.org 23 (February 2018); Reed, “Clientelist Foundations.”

- Walter Benn Michaels and Adolph Reed, Jr., “The Trouble with Disparity,” nonsite.org 32 (September 2020). Reprinted in Michaels and Reed, No Politics but Class Politics (London: ERIS Press, 2023).

- Adolph Reed, Jr., “The South: The Past, Historicity, and Black American History (Part 1),” U.S. Intellectual History Blog, April 3, 2023; and Adolph Reed, Jr., “The South: The Past, Historicity, and Black American History (Part 2),” U.S. Intellectual History Blog, April 10, 2023.

- Reed and Reed, “Evolution of ‘Race,’” 122; Adolph Reed, Jr., “Bayard Rustin: The Panthers Couldn’t Save Us Then Either,” nonsite.org 41 (January 2023); Adolph Reed, Jr., “The Surprising Cross-Racial Saga of Modern Wealth Inequality,” The New Republic, June 29, 2020; Adolph Reed, Jr., “Want to Turn the Pitiless March of Gentrification Into a Parable of Progress? The New York Times Shows Just How It’s Done,” The Nation, April 4, 2023. And who doubts that the eventual outcome of the San Francisco reparations program will be, instead of a preposterously large sum of individual transfer payments, an earnest public Confiteor rejecting the benighted past in favor of the neoliberal ideal of equal opportunity before the logic of the market? And, if it has any material effect at all, that it will be a much less preposterous sum set aside in race-targeted development funds that will make rich black people richer, accompanied by tinkle-down underclass-correction programs propagating the Gospel of Prosperity in the place where redistribution should be?

- Kenneth W. Warren, So Black and Blue: Ralph Ellison and the Occasion of Criticism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 27.