The Lessons of the World Cup for our Victim Culture

That we are living in an age of victim culture is well-exemplified by an article recently published by the CBC suggesting that minorities “feel apprehensive about heading into the wild because they don’t see themselves reflected in the outdoor industry and media.” The underlying premise is that a paucity of representations of members of these groups constructs the outdoors as a kind of “unsafe space” of which people from these communities ask, according to the African-American author of a book called The Adventure Gap, James Mills, “‘Do I belong here? And if somebody believes that I don’t belong here, will they do something to harm me?’”

Now, evidence provided in the article is scant, relying mainly on anecdotes. I could easily provide many to the contrary. But, surely, even if the evidence did support the claim, the important question is to what extent does the article not simply reproduce a certain Catch-22 rather than pointing beyond it. The paradox is the following: There are no people who look like me engaging in activity X, so I don’t feel comfortable engaging in that activity. Because I don’t feel comfortable engaging in activity X, there will be no people who look like me engaging in that activity. What journalism such as this fails to address is how people from marginalized communities, historically, were able to take chances and strike out in new directions and, occasionally, placed themselves in real danger, but also experienced real satisfactions from breaking through barriers (real or perceived) preventing them from participating in certain activities or fields. Such a possibility seems to be ruled out by this kind of writing.

Now, evidence provided in the article is scant, relying mainly on anecdotes. I could easily provide many to the contrary. But, surely, even if the evidence did support the claim, the important question is to what extent does the article not simply reproduce a certain Catch-22 rather than pointing beyond it. The paradox is the following: There are no people who look like me engaging in activity X, so I don’t feel comfortable engaging in that activity. Because I don’t feel comfortable engaging in activity X, there will be no people who look like me engaging in that activity. What journalism such as this fails to address is how people from marginalized communities, historically, were able to take chances and strike out in new directions and, occasionally, placed themselves in real danger, but also experienced real satisfactions from breaking through barriers (real or perceived) preventing them from participating in certain activities or fields. Such a possibility seems to be ruled out by this kind of writing.

Victim Culture

By “victim culture” I mean a constellation of assumptions, values and norms that suggest oppressed groups need to be sheltered in particular ways from prejudice, bias or worse. This has already been an increasingly common refrain in many institutions of higher education, although, happily, it’s one that doesn’t particularly resonate at my own, at least not yet. Such a refrain holds that students require protection from dangerously “triggering” literature or art works, where “safe spaces” need to be constructed exclusively for female or minority students where they won’t have to interact with menacing white men. And where students are increasingly shielded from having to actually make arguments in response to perspectives they may disagree with. Victim culture is a form of infantilization as feminist cultural critic Laura Kipnis has argued.

This kind of rhetoric has spilled over into the public sphere. Not too long ago, for example, trans activists demanded that certain books be taken off the shelves of the now-defunct Vancouver Women’s Library (VWL) because they made the space “unsafe.” A local bookstore that had the temerity to supply the VWL with books was threatened with a city-wide boycott. This was far from the worst of it.

As the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre argued, rather than being determined by a pre-given essence, we first exist in the world and then decide what sort of person to become. While there are clearly social and historical limits to such freedom, Sartre was on to something important. We are human to the extent that we take up freedom as kind of a project. Before their estrangement, Sartre was close to writer Albert Camus. Camus contended that human existence was “absurd,” that it entailed a Sisyphean search for order in a disordered world. The only defensible response was a perpetual act of rebellion at this condition. Significantly, Camus, one time the goalkeeper for the University of Algiers, famously stated that, “What I know most surely about morality and the duty of man, I owe to football.” As a keeper he was the quintessential outsider.

While it’s possible to point to any number of courageous acts of rebellion from Spartacus, to Rosa Parks to “Tank Man” in Tiananmen Square to Pussy Riot, in the immediate aftermath of the World Cup football might just hold some further moral lessons for us today. A French squad boasting some 18 players of African descent beat a feisty Croatia 4-2. One of their goals was scored by teenage sensation of Algerian-Cameroonian descent Kylian Mbappé.

Mbappé is the heir of Camus. While U.S. President Donald Trump hailed the victory shortly after the game’s conclusion, he was oblivious of its irony coming only a couple of days after his statement that “immigration was destroying the fabric of European culture.” The chant resonating on the Avenue Champs-Élysées was equalité, fraternité and Mbappé!

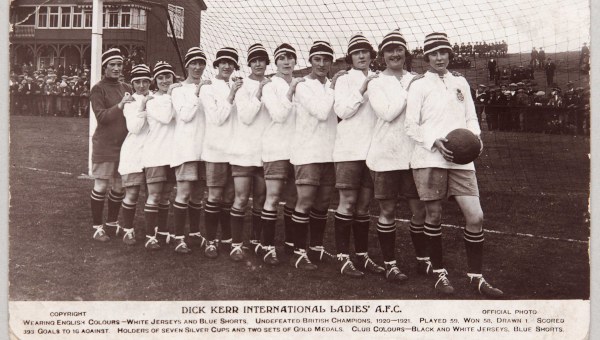

France isn’t the only side to prominently feature immigrants in its squad, the same is true of teams like top-ranked Germany and semifinalists Belgium and England. England is an especially remarkable case insofar as, historically, its game has been particularly rived by virulent post-colonial racism and exclusion. It’s easy to think that black players – the so-called Windrush generation arriving in the U.K. from the Caribbean between 1948-1971 – have always dominated the English Premier League, but this is simply not the case. Only a short four decades ago did players like Laurie Cunningham, Viv Anderson and John Barnes break into the game against massive odds.

Football, Race and Racism

The brutalities of football and race, I know intimately and first-hand. I first visited London in 1973 to meet my grandfather who had been expelled from Idi Amin’s Uganda and now lay dying. I recall quite vividly watching the FA Cup Final on the telly (Sunderland beat Leeds United 1-0), but also the fearful tones in which my relatives spoke of the very dangers posed to Asians around football stadiums. They lived close to the storied Wembley Stadium, the site of England’s first and only World Cup victory some seven years earlier.

Despite my family’s emphatic warning, I fell in love with the beautiful game and would return less than a decade later on trials for Aberdeen and Leicester City Football Club. There certainly was no one who looked like me in British football, but I was oblivious. When I entered the dressing room I felt like a “brother from another planet;” Scotland great Gordon Strachan asked me point blank, “What are you doing here?” On the pitch I was targeted with racial epithets and intimidation and I recall vividly the way a Leicester City coach kept referring to me in training as “Abdullah.” I nearly didn’t survive the journey by night train from Aberdeen with a mob of “Paki-bashing” Arsenal supporters.

Despite the racism of the early 1970s, black players persisted in England as elsewhere and the genuinely anti-racist effects of their heroic strides can hardly be overstated. When the racists of the English Defence League or the French Front National today seek to hold up their national team as the model of ethno-nationalist virtue they come up against what is for them embarrassing multicultural, civic representation of their respective nations.

Black players endured brutal fouls from other players on the pitch, as well as verbal and other forms of abuse from the fans in the stands, and made names for themselves playing for the national team and, perhaps more importantly, opening doors for generations of players that followed in their footsteps. What if these players, in keeping with “victim culture,” had said to themselves: “I don’t see anyone out on the pitch like me, it’s not a ‘safe space,’ so I won’t play?” If these rebels hadn’t somehow found the courage to strike out in bold, new and, frankly, dangerous directions, the football world and, more importantly, anti-racist struggles around the globe would be all the poorer for it. •

This article first published on the Vancouver Sun website.