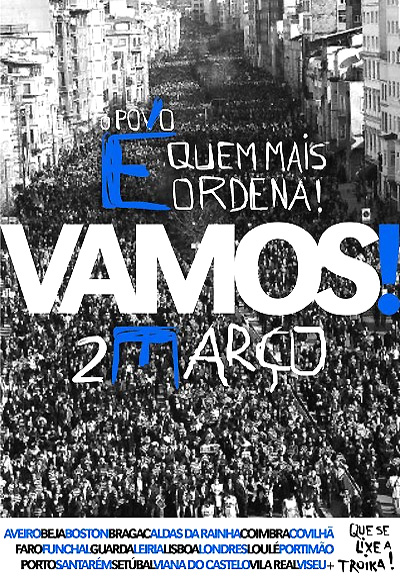

On Saturday, 2 March 2013, “Que Se Lixe a Troika” (Fuck the Troika) demonstrations represented a qualitative as well as quantitative shift for the anti-austerity movement in Portugal. In more than 40 towns and cities across Portugal, 1.5 million people (800,000 in Lisbon) took to the streets against the government’s slavish submission to the dictates of the Troika of IMF, ECB, and EU. In the wake of the first “Que Se Lixe a Troika” demonstration on 15 September, an ongoing militant dockers’ strike, and a general strike on 14 November of last year, Saturday’s demonstration is starting to tackle the unfinished business of the 1974 Portuguese Revolution.

Portugal’s rulers are trembling. In the run-up to the demonstration on Saturday, the Lisbon City Council removed all loose cobblestones along the demonstration route in the city center. This comes after protests have been steadily radicalizing in the course of a few months. Clashes between police and protesters in front of parliament, revolutionary murals going up in city centers, protesters piling up rubbish in front of banks, and government ministers being insulted by the public are commonplace in Portugal 2013.

Portugal’s rulers are trembling. In the run-up to the demonstration on Saturday, the Lisbon City Council removed all loose cobblestones along the demonstration route in the city center. This comes after protests have been steadily radicalizing in the course of a few months. Clashes between police and protesters in front of parliament, revolutionary murals going up in city centers, protesters piling up rubbish in front of banks, and government ministers being insulted by the public are commonplace in Portugal 2013.

Students at the ISCTE University in Lisbon hit the headlines in recent weeks when they heckled Deputy Prime Minister Miguel Relvas in front of live television cameras and forced Relvas to flee the building while students sang the revolutionary anthem “Grândola, Vila Morena.” The action resonated with millions of people glued to their TV screens as Relvas has been under attack for obtaining his university degree from a private university in a matter of a year.

Greek-Style Austerity

Once labeled “the good pupil of the Eurozone,” Portugal is quickly turning into a Greek-style laboratory of austerity and neoliberalism. Unemployment now stands at 17.5 per cent with one and a half million people out of work. According to Eurostat figures about 24 per cent of the Portuguese population live below the poverty threshold. The economy is estimated to contract by two points this year. While this manifests itself in a sharp drop in domestic consumption the continued instability of the Eurozone adds fuel to the flames. Cuts to healthcare and the welfare state as well as diminishing purchasing power is making life unbearable for millions of Portuguese people.

This week European Finance Ministers will meet in Brussels to discuss the re-negotiation of the terms of the 2011 bailout. Portugal’s debt is expected to reach 120 per cent of GDP this year and the country currently pays 3.6 per cent interest on troika loans. It has committed itself to selling off five million euros worth of state assets. Most recently, Portugal’s sewage and drinking water has been privatized. In December, the government sold its shares of the profitable airport provider ANA to the French company VINCI for a bargain price, making sure that the European Union’s built-in mechanism of redistribution from South to North is maintained.

However, in an ironic twist of events, companies from Portugal’s ex-colonies have seized the opportunity for revenge. Angola’s Banco BIC is buying Portugal’s nationalized, scandal-ridden Banco Português de Negócios (BPN) for a fraction of its €180-million asking price. An Angolan company has already bought Portugal’s biggest furniture maker, and Portuguese construction companies such as Teixeira Duarte, Soares da Costa, and Mota-Engil have been switching from their domestic market to Angola. On the other side of the Atlantic, Brazilian businessmen are still eyeing up the Portuguese airline TAP after a failed deal in early December. And a Brazilian cement maker and a Brazilian steelmaker have clashed over control of Cimentos de Portugal.

Crisis of Hegemony

It is no surprise that the governing coalition has hit rock bottom in the opinion polls and that the crisis of hegemony has been sharpening in recent weeks and months culminating in Saturday’s protests. Twitter, Facebook, and the blogosphere indicated weeks ago that Saturday’s demonstration would be a massive display of people’s power. The events on Saturday confirmed this and established “Que Se Lixe a Troika” as a movement and a new political actor in Portugal’s austerity debate.

Saturday’s demonstration succeeded in uniting three strands of the resistance: The “indignant” with their homemade placards have been one of the most exciting features of the last six months of struggle. With humorous and biting slogans such as “I prefer the horses in my lasagne to the donkeys in the government,” they have captured the rage of a people failed by capitalism. The students of Estudantes pela Greve Geral, the precarious workers of Precários Inflexíveis, and the situationist-like direct action group Exército de Dumbledore, who have been coordinating and building networks since the mid-2000s, are successfully mobilizing people beyond their classrooms, reading groups, squats, and social centers into a movement which has the power to turn the tide on neoliberalism.

The trade unionists of the main trade union confederation CGTP have been spurred into action by this political movement as well as its own successive general strikes, days of actions, and local disputes. This week TAP employees will be protesting the government’s attacks on the industry by holding a giant replica one-way ticket to Toronto for Economics Minister Álvaro Santos Pereira. On March 21-23 workers will strike for 48 hours.

The movement’s reference point is the 1974 revolution. The choreographed singing of the revolutionary hymn “Grândola, Vila Morena” and protesters’ use of the carnation show that this movement isn’t about cosmetic changes to government policy expected after September 15 when protesters successfully forced the government to back down from its proposal to increase social security contributions from workers and decrease those of bosses.

Instead, the new movement is aiming to get the old unfinished business of the revolution done. Inasmuch as Zeca’s revolutionary song acts as the link between different and disparate struggles against austerity, it also extends the collective memory of the revolution to a new generation of activists who don’t have the same political structures, parties, and institutions of workers’ power as during the height of the revolution.

The votes of censure against the government at the end of the demonstrations on Saturday, though, showed that the movement can start to create the kind of organizations that the struggle so desperately needs. Town after town, city after city voted to censure the government in mass assemblies. Echoing the spirit of Tahrir Square, Puerta del Sol, Syntagma, and the Wisconsin Senate occupation, the protesters sent a clear signal of defiance to the government. Now, activists should learn from the people’s defiance and hold such votes of censure in workplaces, universities, and neighborhoods. This could create the kind of movement that could once again replace horsemeat with beef and kick the donkeys out of government. •

Mark Bergfeld was an international delegate to the Left Bloc Congress and reported on the general strike from Lisbon on November 14, 2012. This article first appeared on the MRzine website.