Two Views on the NATO Military Intervention in Libya

The United Nations-NATO military intervention in the Libyan civil war has posed a challenging question for socialists in Canada – all the more given the active participation of the Canadian armed forces in the air war.

This raises some difficult questions – should socialists in Canada have supported the March 17 U.N. Security Council initiative to impose a “no-fly zone” over Libya in order to protect civilians against a possible massacre by forces led by Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi? Or is this just another imperialist intervention that will make matters on the ground worse, and impose its own will on the outcome of what is essentially a civil war? Will the NATO forces go beyond the U.N. resolution of “no-fly zone” to explicit regime change.

What is our alternative to the Canadian government’s present course of making war on Libya?

Once NATO air strikes began on March 19, the scope of the intervention broadened quickly. The “no-fly zone” has become a broader NATO air war against Gaddafi forces. The leading interventionist powers are reportedly meeting in London, supposedly to plan Libya’s future. Nonetheless, the debate among socialists over the U.N. “no-fly” resolution illuminates the basic issues in this conflict.

These are genuine divisions in political assessment, that the Left needs to keep debating in terms of our differences and strategies. Certainly, in terms of Libya but also with respect to the wider Arab revolts shaking one bankrupt regime after another. The differences also reflects, it needs stating, the more general weakness of the global Left. We are unable, at this point in time, to shift the international correlation of political forces, and thus are left responding to the intervention of the imperialist powers from a vantage of weakness. There is no capacity for a thorough-going socialist intervention, that would alter the terms in which both the imperialists and the rebels make their calculations.

In a recent intervention, Phyllis Bennis concludes:

“The U.S.-led (NATO cover or not) military intervention [in Libya] is underway. Our job now is to make sure it does not escalate even further into full-scale invasion, and to try to end it as soon as possible. And then to work as hard as we can to support the efforts to consolidate and expand the extraordinary accomplishments of the uprisings of the 2011 Arab Spring in Libya and the rest of the region.”

In the articles published below, two of the socialists most active in defending movements for democracy and social change in the Mideast present contrasting views on the U.N. resolution and the resulting intervention.

Gilbert Achcar, arguing for a position of not opposing the U.N. initiative in the strict terms passed, is a Lebanese Marxist and long-time defender of liberation movements in the Middle East, now teaching at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

Kevin Ovenden, argues for opposition to the U.N. initiative in itelf, as well as the likely consequences for further actions by the imperialist powers, is a London-based Marxist, antiwar activist, member of the executive of the Respect Party, and leader of Viva Palestina.

— The Bullet

Libya: A Legitimate and Necessary Debate

From an Anti-Imperialist Perspective

Gilbert Achcar

“The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was indeed a compromise with the imperialists, but it was a compromise which, under the circumstances, had to be made. … To reject compromises ‘on principle,’ to reject the permissibility of compromises in general, no matter of what kind, is childishness, which it is difficult even to consider seriously … One must be able to analyze the situation and the concrete conditions of each compromise, or of each variety of compromise. One must learn to distinguish between a man who has given up his money and fire-arms to bandits so as to lessen the evil they can do and to facilitate their capture and execution, and a man who gives his money and fire-arms to bandits so as to share in the loot.” – Vladimir I. Lenin

The interview I gave to my good friend Steve Shalom the day after the U.N. Security Council adopted resolution 1973 and which was published on ZNet on March 19 provoked a storm of discussions and statements of all kinds – friendly, unfriendly, strongly supportive, mildly supportive, politely critical or frenziedly hostile – far larger than anything I could have expected, all the larger because it was translated and circulated into several languages. If this is an indication of anything, it is that people felt there was a real issue at stake. So let’s discuss it.

The debate on the Libyan case is a legitimate and necessary one for those who share an anti-imperialist position, lest one believes that holding a principle spares us the need to analyze concretely each specific situation and determine our position in light of our factual assessment. Every general rule admits of exceptions. This includes the general rule that U.N.-authorized military interventions by imperialist powers are purely reactionary ones, and can never achieve a humanitarian or positive purpose. Just for the sake of argument: if we could turn back the wheel of history and go back to the period immediately preceding the Rwandan genocide, would we oppose an U.N.-authorized Western-led military intervention deployed in order to prevent it? Of course, many would say that the intervention by imperialist/foreign forces risks making a lot of victims. But can anyone in their right mind believe that Western powers would have massacred between half a million and a million human beings in 100 days?

This is not to claim that Libya is Rwanda: I’ll explain in a moment why Western powers didn’t bother about Rwanda, or don’t bother about the death toll of genocidal proportions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but intervene in Libya. Reference to the Rwandan case is given here only to show that there is room for discussion of concrete cases, even though one adheres to firm anti-imperialist principles. The argument that Western intervention in Libya is bound to make civilian victims (I’d actually care even for Gaddafi’s soldiers from a humanitarian perspective) is not determinative. What is decisive is the comparison between the human cost of this intervention and the cost that would have been incurred had it not happened.

To take another extreme analogy for the sake of showing the full range of discussion: could Nazism be defeated through non-violent means? Were not the means used by the Allied forces themselves cruel? Did they not savagely bomb Dresden, Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing huge numbers of civilians? In hindsight, would we now say that the anti-imperialist movement in Britain and the United States should have campaigned against their states’ involvement in the world war? Or do we still believe that the anti-imperialist movement was right in not opposing the war against the Axis (as it was right indeed in opposing the previous one, the 1914-18 world war), but that it should have campaigned against any massive harm purposely inflicted upon civilian populations with no evident rationale of a necessity in order to defeat the enemy?

Enough now with analogies. They are always subject to endless debates, even though they serve the useful purpose of showing that there can be situations where there can be a debate, situations where you have to give up to bandits, or call the cops, etc. They show that the belief that any such attitudes should be automatically rejected as a “breach of principles,” without taking the trouble of assessing the concrete circumstances, is just unsustainable. Otherwise, the anti-imperialist movement in Western countries would appear as only concerned with opposing their own governments without giving a damn about the fate of other populations. This is no longer anti-imperialism, but right-wing isolationism: the “let them all go to hell, and leave us in peace” attitude à la Patrick Buchanan. So let us calmly assess the concrete situation that we’re dealing with these days.

We shall begin with the nature of Gaddafi’s regime. The facts here leave little room for legitimate disagreement. It is only for the attention of those who believe, in good faith and out of sheer ignorance, that Gaddafi is a progressive and an anti-imperialist that I discuss it. True, Gaddafi started as a relatively progressive anti-imperialist populist dictator, who led a military coup against the Libyan monarchy in 1969 imitating the Egyptian coup that toppled the monarchy there in 1952. His first hero was Gamal Abdel-Nasser, although his regime was initially more right-wing ideologically, with much more emphasis on religion (later, Gaddafi pretended to give a new interpretation of Islam). He started very early on recruiting people from poorer countries as mercenaries in his armed forces, initially for the Islamic Legion that he set up.

He proclaimed the replacement of existing laws with the Sharia in the early 1970s, just before embarking on an imitation of the Chinese “cultural revolution,” with his own Islamic version of Mao’s Little Red Book: the Green Book. He also imitated the pretense of the “cultural revolution” of instituting “direct democracy,” through the creation of a system of “popular committees” supposedly turning Libya into a “state of the masses” – actually one with a record proportion of people on the payroll of the security services. More than 10% of the Libyan population were “informants” paid for exerting surveillance over the rest of the society. Gaddafi extensively jailed or executed opponents to his regime, including several of the officers who had taken part along with him in the overthrow of the monarchy. In the late 1970s, he decided to turn the Libyan economy into a combination of state capitalism in large enterprises and private capitalism with workers’ “partnership” in smaller ones and abolish rents and retail trade (even hairdressers were nationalized!). He also devoted part of the state’s oil revenue to improving the living conditions of Libya’s citizens, a “revolutionary” version of the way in which some of the Gulf monarchies with high per capita oil income cater to the needs of their own citizens in order to buy themselves a social constituency – while, as in Libya, mistreating the immigrant workers who constitute a major part of their labour force and their population.

In the next decade, faced with the disastrous results of his erratic policies and the crisis of the USSR, upon which he depended for his arms purchases, Gaddafi pretended to imitate Gorbachev’s perestroika, liberalizing Libya’s economy, but hardly its political life. His next major political turnabout took place in 2003. In December of that year, he came to the political rescue of Bush & Blair, announcing that he had decided to renounce his weapons of mass destruction programs. This was badly needed boost for the credibility of the invasion of Iraq as a way of halting WMD proliferation. Gaddafi was suddenly turned into a respectable leader and was warmly congratulated, with Condoleezza Rice citing him as a model. One after the other, Western leaders flocked to Libya paying him visits in his tent and concluding juicy contracts. The one who built the closest relation with him is Italian hard-right and racist prime minister Silvio Berlusconi: his friendship with Gaddafi was not only very fruitful economically. In 2008 they concluded one of the dirtiest deals of recent times, agreeing that poor boat people from the African continent intercepted by Italian naval forces while trying to reach European shores would be delivered directly to Libya instead of being taken to Italian territory, where they would have to be screened for asylum. This deal was so effective that it reduced the number of such asylum-seekers in Italy from 36,000 in 2008 to 4,300 in 2010. It was condemned by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, to no avail.

The idea that Western powers are intervening in Libya because they want to topple a regime hostile to their interests is just preposterous. Equally preposterous is the idea that what they are after is laying their hands on Libyan oil. In fact, the whole range of Western oil and gas companies is active in Libya: Italy’s ENI, Germany’s Wintershall, Britain’s BP, France’s Total and GDF Suez, U.S. companies ConocoPhillips, Hess, and Occidental, British-Dutch Shell, Spain’s Repsol, Canada’s Suncor, Norway’s Statoil, etc. Why then are Western powers intervening in Libya today, and not in Rwanda yesterday and Congo yesterday and today? As one of those who have energetically argued that the invasion of Iraq was “about oil” against those who tried to outsmart us by saying that we were “reductionists,” don’t expect me to argue that this one is not about oil. It definitely is. But how?

My take on that is the following. After watching for a few weeks Gaddafi conducting his terribly brutal and bloody suppression of the uprising that started in mid-February – estimates of the number of people killed in early March ranged from 1000 to 10,000, the latter figure by the International Criminal Court, with the Libyan opposition’s estimates ranging between 6,000 and 8,000 – Western governments, like everybody else for that matter, became convinced that with Gaddafi set on a counter-revolutionary offensive and reaching the outskirts of Libya’s second largest city of Benghazi (over 600,000 inhabitants), a mass-scale slaughter was imminent. To give an indication of what such repressive governments can perpetrate, just think of the fact that the Syrian regime’s 1982 repression of the uprising in the city of Hama, with less than one third of Benghazi’s population, resulted in over 25,000 deaths. Had a massacre on a similar scale occurred with Gaddafi’s rule consolidating as a result, Western governments would have had no choice but to impose sanctions and an oil embargo on his regime.

The conditions of the oil market that prevailed in the 1990s were characterized by a depression in prices, at a time when the U.S. was going through its longest economic expansion ever, the bubble-sustained boom of the Clinton years. It was very comfortable for Washington and its allies to maintain an embargo on Iraq during that decade (at a quasi-genocidal cost). It is only at the end of the decade that the oil market started moving out of depression into a rise of prices that everything indicated to be of a structural nature, i.e. a long-term rising tendency. And it is no coincidence that George W. Bush and his cronies came out then in favour of “regime change” in Iraq. For it was the condition without which Washington wouldn’t tolerate lifting the embargo on a country whose major oil deals had been granted to French, Russian and Chinese interests (the three leading opponents of the invasion at the U.N. Security Council – surprise, surprise!).

The present conditions of the world oil market are indeed conditions where oil prices, after falling briefly under the shock of the global crisis, have resumed their upward movement, several months before the revolutionary wave in North Africa and the Middle East. This, in a condition of unresolved global economic crisis, with an extremely fragile fake recovery. Under such conditions, an oil embargo on Libya is simply not an option. The massacre had to be prevented. The best scenario for Western powers became the fall of the regime, thus relieving them of the problem of coping with it. A lesser evil option for them would be a lasting stalemate and de facto division of the country between West and East, with oil exports resumed from both provinces, or exclusively from the main fields located in the East under rebel control.

To these considerations one should add the following: it is nonsensical, and an instance of very crude “materialism,” to dismiss as irrelevant the weight of public opinion on Western governments, especially in this case on nearby European governments. At a time when the Libyan insurgents were urging the world more and more insistently to provide them with a no-fly zone in order to neutralize the main advantage of Gaddafi’s forces, and with the Western public watching the events on television – making it impossible that a mass-scale slaughter in Benghazi would go unseen, as it was so often the case in other places (like the above-mentioned Hama, for instance, or the Democratic Republic of the Congo) – Western governments would not only have incurred the wrath of their citizens, but they would have completely jeopardized their ability to invoke humanitarian pretexts for further imperialist wars like the ones in the Balkans or Iraq. Not only their economic interests, but also the credibility of their own ideology was at stake. And the pressure of Arab public opinion certainly played a role in the call by the Arab League of States for a no-fly zone over Libya, even though there can be no doubt that most Arab regimes were wishing that Gaddafi could put down the uprising, and thus reverse the revolutionary wave that has been sweeping the whole region and shaking their own regimes since the beginning of this year.

Now, what do we do with that? A mass uprising, facing an all-too-real threat of large-scale massacre was requesting a no-fly zone in order to help them resist the criminal regime’s offensive. Unlike the anti-Milosevic forces in Kosovo, they were not calling for foreign troops to occupy their land. On the contrary, they had good reason for having no confidence in any such deployment: their awareness, in light of Iraq, Palestine, etc., that world powers have imperialist agendas, as well as their own experience of the way the same world powers cozied up to the tyrant oppressing them. They very explicitly rejected any foreign intervention on the ground, only asking for an air cover. And the UNSC resolution excluded explicitly upon their request “a foreign occupation force of any form on any part of Libyan territory.”

I won’t dwell on the unacceptable arguments of those who try to shed doubt on the nature of the uprising’s leadership. They are most often the same as those who believe Gaddafi is a progressive. The leaders of the uprising are a mix of political and intellectual democratic and human rights dissidents, some of whom have spent long years in Gaddafi’s jails, men who broke with the regime in order to join the rebellion, and representatives of the regional and tribal diversity of the Libyan population. The program they are united on is one of democratic change – political freedoms, human rights, and free elections – exactly like all other uprisings in the region. And if there is no clarity about what a post-Gaddafi Libya might look like, two things are certain: it can’t be worse than Gaddafi’s regime, and it can’t be worse than the quite more obvious likely scenario of a crucial role of the fundamentalist Muslim Brotherhood in post-Mubarak Egypt, given by some as an argument for supporting the Egyptian dictator.

Can anyone claiming to belong to the left just ignore a popular movement’s plea for protection, even by means of imperialist bandit-cops, when the type of protection requested is not one through which control over their country could be exerted? Certainly not, by my understanding of the left. No real progressive could just ignore the uprising’s request for protection – unless, as is too frequent among the Western left, they just ignore the circumstances and the imminent threat of mass slaughter, paying attention to the whole situation only once their own government got involved, thus setting off their (normally healthy, I should add) reflex of opposing the involvement. In every situation when anti-imperialists opposed Western-led military interventions using massacre prevention as their rationale, they pointed to alternatives showing that the Western governments’ choice of resorting to force only stemmed from imperialist designs.

There was a non-violent solution out of the Kosovo crisis: for one, the offer made by Yeltsin’s Russian government in August 1998 of an international force to implement a political settlement jointly imposed by Moscow and Washington. It was relayed by then U.S. ambassador to NATO Alexander Vershbow, and just ignored in Washington. The same could be added about February 1999. The Serbian and NATO positions were different, but negotiable, as was shown after 78 days of bombing, when the U.N. resolution was a compromise between them. There was a non-violent solution to get Saddam Hussein to withdraw his troops from Kuwait in 1990: aside from the fact that he could not have withstood for long the tight sanctions that were imposed on his regime in order to force him out, he was offering to negotiate his withdrawal. Washington preferred to destroy the country’s infrastructure and send it “back to the stone age,” as the reporter for the UNSC described the country’s situation after the war in 1991.

What then was the alternative to the no-fly zone in the Libyan case? None is convincing. The day when the UNSC voted its resolution, Gaddafi’s forces were already on the outskirts of Benghazi, and his air force attacking the city. A few days more, they might have taken Benghazi. Those who are confronted with this question give very unconvincing answers. A political solution could have been contemplated had Gaddafi been willing to allow free elections, but he wasn’t. He and his son Saif gave the uprising no choice other than surrender (promising them an amnesty that nobody could have trusted), or “civil war.” I’ll ignore those who say that the population of Benghazi could have fled to Egypt and taken refuge there! It is not worthy of comment. I’ll also ignore those who say that Arab armies only should have intervened, as if an intervention by the likes of the Egyptian and Saudi armed forces would have caused fewer casualties, and represented less imperialist influence on the process in Libya. The answer that sounds more convincing is the one advocating arms delivery to the insurgents; but it was not a plausible alternative.

Arms delivery could not be organized and become effective – especially if we’re thinking of sophisticated anti-aircraft missiles – in 24 hours! This could not have been an alternative to a massacre foretold. Under such conditions, in the absence of any other plausible solution, it was just morally and politically wrong for anyone on the left to oppose the no-fly zone; or in other words, to oppose the uprising’s request for a no-fly zone. And it remains morally and politically wrong to demand the lifting of the no-fly zone – unless Gaddafi is no longer able to use his air force. Short of that, lifting the no-fly zone would mean a victory for Gaddafi, who would then resume using his planes and crush the uprising even more ferociously than what he was prepared to do beforehand. On the other hand, we should definitely demand that bombings stop after Gaddafi’s air means have been neutralized. We should demand clarity on what air potential is left with Gaddafi, and, if any is still at his disposal, what it takes to neutralize it. And we should oppose NATO turning into a full participant of the ground war beyond the initial blows to Gaddafi’s armor needed to halt his troops’ offensive against rebel cities in the Western province – even were the insurgents to invite NATO’s participation or welcome it.

Does it mean that we had and have to support UNSC resolution 1973? Not at all. This was a very bad and dangerous resolution, precisely because it didn’t define enough safeguards against transgressing the mandate of protecting the Libyan civilians. The resolution leaves too much room for interpretation, and could be used to push forward an imperialist agenda going beyond protection into meddling into Libya’s political future. It could not be supported, but must be criticized for its ambiguities. But neither could it be opposed, in the sense of opposing the no-fly zone and giving the impression that one doesn’t care about the civilians and the uprising. We could only express our strong reservations. Once intervention started, the role of anti-imperialist forces should have consisted in monitoring it closely, and condemning all actions hitting at civilians where measures to avoid such killings have not been observed, as well as all actions by the coalition that are devoid of a civilian protection rationale. One article of the UNSC resolution should definitely be opposed though: it is the one confirming the arms embargo on Libya, if this means the country and not the Gaddafi regime alone. We should on the contrary demand that arms be delivered openly and massively to the insurgents, so that they no longer need direct foreign military support as soon as possible.

A final comment: for so many years, we have been denouncing the hypocrisy and double standard of imperialist powers, pointing to the fact that they didn’t prevent the all-too-real genocide in Rwanda while they intervened in order to stop the fictitious “genocide” in Kosovo. This implied that we thought that international intervention should have been deployed in order to prevent or stop the genocide in Rwanda. The left should certainly not proclaim such absolute “principles” as “We are against Western powers’ military intervention whatever the circumstances.” This is not a political position, but a religious taboo. One can safely bet that the present intervention in Libya will prove most embarrassing for imperialist powers in the future. As those members of the U.S. establishment who opposed their country’s intervention rightly warned, the next time Israel’s air force bombs one of its neighbours, whether Gaza or Lebanon, people will demand a no-fly zone. I, for one, definitely will. Pickets should be organized at the U.N. in New York demanding it. We should all be prepared to do so, with now a powerful argument.

The left should learn how to expose imperialist hypocrisy by using against it the very same moral weapons that it cynically exploits, instead of rendering this hypocrisy more effective by appearing as not caring about moral considerations. They are the ones with double standards, not us. •

This article was first published on the europe-solidaire.org website.

The Arab Revolution Must Stay in Arab Hands: A Response to Gilbert Achcar

Gilbert Achcar interviewed by Farooq Sulehria

The Arab revolution has widened the left’s horizons. In the region itself there is now a historic possibility of a new radical politics: successful resistance to the hegemonic Western powers and to Israel fused with the movement of the young and propertyless masses against the corrupt and complicit elites.

The fall of Ben Ali and Mubarak shattered decades of Western policy, rocking them onto the back foot. They are now moving onto the front foot, as the regional despots raid their political and military arsenals to cling on.

Thus the developing Arab movements and the left face new political challenges and strategic choices. That is the context of the legitimate debate Gilbert Achcar has framed over the Western military intervention in Libya.

Gilbert outlines a case for qualified political support for the soon to be NATO-commanded air and naval operations in Libya (no one on the international left is in a position to do anything materially/militarily themselves).

He writes as a well known Marxist and opponent of the Afghan and Iraq wars, a supporter of the Palestinian struggle and a genuine friend of the most radical edge of the Arab revolutions.

Gilbert Achcar is no part of the liberal attack pack, who in natural alliance with the neoconservatives brought us the disasters of Afghanistan and Iraq. But he argues that over Libya the left should support the action of powers who occupy those two countries, albeit with many caveats and with vigilant suspicion.

It is a badly mistaken position over Libya. When its logic is generalised – as Gilbert does – it plays dangerously into the hands of the reactionary forces which he and the left hope the Arab revolutions will eventually eradicate.

Western Intervention Across the Region

Gilbert introduces two analogies to make the point that socialist principles are not articles of religious faith and are no substitute for providing concrete answers based on a “factual assessment” of concrete situations.

The point is helpful: the analogies, not. As he acknowledges, proceeding by analogy tends to generate confusing polemics over what is common between unique events, each of which is itself the subject of considerable controversy and of radically different factual assessments.

The Rwandan genocide, one of his examples, is arguably (at the very least) more a horrific lesson in the consequences of actual Western intervention, in its totality up to and including the eve of the slaughter, than it is a counter-example for those Gilbert takes to task for a “religious” opposition to all Western military action.

In any case, even the Western leaders who have driven the Libya bombing have not suggested that the events they say they forestalled were analogous to the Holocaust or the Rwandan genocide – though the most rabid tabloids and the bomberatti have. It is self-defeating for the left to insert those connotations ourselves. It is even more damaging if we at the same time fail to foreground the most salient and distinctive feature of which the uprising in Libya is an expression – the wider Arab revolutionary upheaval.

That regional process, and what it means both for the Western powers and for those who have risen up in Libya, barely features in Gilbert’s analysis. Instead, he largely accepts the question as Nicolas Sarokzy, David Cameron and Barack Obama frame it: a particular, Libyan moral dilemma confronting their publics and states, whose wider actions are cropped out.

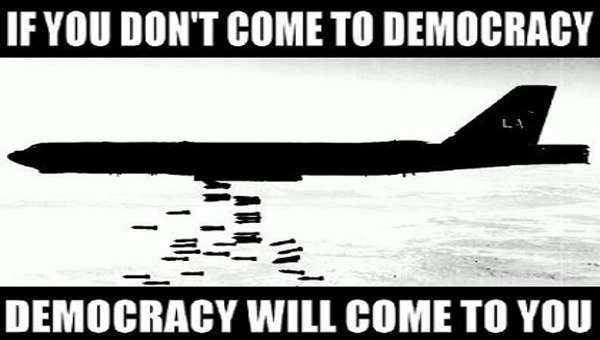

But their military action is not some singular response to a potential humanitarian crisis. It is more even than the latest chapter in a history of wars attended by specious humanitarian claims. That said, history alone – recent and ongoing in Iraq and Afghanistan – should cause anyone who hopes for a progressive outcome to this bombing or who invests it with moral worth to pause and reflect.

The bloody past and present also contribute to the rational underpinning of a far from “religious” anti-war sentiment, which goes beyond the left to embrace an unprecedentedly large section of public opinion – a testament to the international movement against the Iraq war.

The context, however, is not merely historical. The same actors who are launching missile strikes over Libya are intervening at the same time and with the same objectives across the rest of the same region. (Unless we are unfeasibly to imagine that their motives, interests and aims are fundamentally different in Libya and in the Gulf – an unsustainable moral-political atomism, certainly for a Marxist.)

The same European Union mandarin – civilising-colonialist Robert Cooper – is briefing about bringing democracy to Libya and also writing apologias for the Saudi-orchestrated murder of democrats in Bahrain.

The same President Obama who said that attacks on hospitals were a casus belli against Tripoli is standing by his allies in Riyadh and Manama, who spent many days… attacking hospitals under the noses of the U.S. Fifth Fleet.

The same Treasury revenue going up in smoke as missiles explode in Libya is subsidising Israel’s missiles blowing up people in Gaza – not two years ago, but today, now, with the threat of much more imminently.

The same Qatar that is belatedly providing air support for the attacks in Libya is simultaneously sending troops to attack democrats in the Persian Gulf.

For sure, there are great fractures and differences of emphasis as the U.S. with its European and Arab allies seeks to cohere a response to the challenge posed by the Arab revolutions.

The U.S. would like more palliative reforms from the Kings of Arabia; the Saudis want to give none. Hillary Clinton has cleaved as long as possible to the autocrat in Yemen; Alain Juppe, stung by the political crisis wrought by his predecessors’ intense relationship with Ben Ali, called earlier for Ali Abdullah Saleh to go.

But the overall aim is the same: to corral the revolutionary process and ensure it is steered along a path which is stable and compatible with the interests of the Western powers and whichever safe pairs of hands they can identify in each state.

Oil and Western Policy

Those interests do ultimately come down to the control of Middle Eastern and North African hydrocarbons. Is the West’s policy about oil? On one level it is always about oil. When Silvio Berlusconi and Sarkozy embraced Muammar Gaddafi, the unspoken interest was oil. When they find themselves intervening to overthrow him, the underlying interest remains oil – just as it was when the West supported Saddam Hussein in his attack on revolutionary Iran and then, a decade later, drove him out of Kuwait, embargoed Iraq for 12 years, finally invading a second time and executing him.

The same imperial, capitalist objectives in the region can be served by different politiques d’Etat; to paraphrase Lord Palmerston, imperial chancellories have no eternal friends and no eternal enemies, only eternal interests – as Hosni Mubarak discovered at the eleventh hour.

So why the change in policy toward Gaddafi? There are those who serially tell us that this time it’s different, this time the Western governments are subordinating self-interest to humanitarianism. Gilbert is not one of them. But his argument lends them credibility – and if adopted by the left would encourage them to go further.

Gaddafi managed neither to fall on his sword, like Mubarak, nor to crush the opposition, like the Al Khalifa kleptocrats in Bahrain – but only after the intervention of the U.S.’s oldest ally in the region, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

He did succeed through vicious repression and playing on sectional divisions in Libyan society in displacing the dynamic of the youth-led revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt (which has also been central in Sanaa, Yemen, for six weeks) with an armed conflict more resembling a civil war.

In those circumstances he became a liability for the West. On the eve of the bombing campaign Obama said that the instability in Libya threatened “vital U.S. allies in the region.”

Gaddafi himself had already proven that he had no intention of posing such a threat. Those who think that he is some kind of anti-imperialist now would do well to reflect that even as he denounced the Western bombardment as “crusader aggression” he was proclaiming himself as the only possible Libyan leader to maintain peace with Israel and to prevent African migrants from entering Europe.

It is preposterous, as Gilbert says, to claim that Gaddafi has been hostile to Western interests over the last decade and that that is why the West want to topple him. But equally, it is evident over two last weeks that the flaking-rule of this recently acquired, flakey ally no longer served them well.

The wrangling in Western capitals over how to respond and bring a return to stability more plausibly reflects the uncertainty that has beset their attempts to rally a riposte to the Arab revolution than it does some dawning recognition of a hitherto absent moral sensibility. Unlike in Egypt, there was no army high command to switch allegiance to smoothly and safely.

The same hesitancy marked the Arab despots. They want an end to the revolutionary wave, but they have no loyalty to, still less liking for, Gaddafi – or necessarily for each other; the Qataris long campaigned for the toppling of Mubarak. The West’s actions are a single axe to fell a two-headed monster, they hope.

Gilbert says we should not “dismiss the weight of public opinion on Western governments” in deciding their actions, justified as preventing a slaughter in Benghazi.

Now, only the self-appointed and deluded leaders of “global civil society” would claim that public opinion in Europe and north America is what drove the decision to go to war. Britain and the U.S. went to war on Iraq despite public opinion.

There is little enthusiasm for this war – that much is clear from the conflicting opinion polls. So we are left with the observation that public outrage at a predicted massacre was just one factor among many in Sarkozy’s and Cameron’s drive to get the missiles launched and bombs dropped.

Morality and Western Bombs

Let us put to one side that it was the dire warnings of the very politicians who pushed for bombing – Juppe and William Hague preeminently – which informed the public discussion about a possible slaughter. Let us also return shortly to whether their warnings were right and what might have been done.

In a limited sense public compassion was significant. It determined the ideological register in which London, Paris and Washington have chosen to relegitimise their roles in the Arab region after the battering they have taken from Iraq and the fall of their allies in Tunisia and Egypt.

Gilbert touches on it when he identifies the West’s concern to ensure a continued “ability to invoke humanitarian pretexts for further imperialist wars like the ones in the Balkans or Iraq.” But that means that giving any credence to their current humanitarian pretext simply makes it easier for them to construct exactly the narrative for more Iraqs.

Emboldened Western powers make further wars more likely. Supporting their military actions contributes to that.

Unless we are to detach Libya from what the Western powers are doing and will do in the region and elsewhere, that consequence surely weighs on one side of the moral balance Gilbert enjoins us to strike: “what is decisive is the comparison between the human cost of this intervention and the cost that would have been incurred had it not happened.” The dead in Bahrain and Yemen deserve to be counted too.

The first cost we will come to know as events unfold in North Africa, the Middle East and beyond. The second, we can never know with certainty.

It has become largely accepted that Gaddafi was about to take Benghazi and would have killed thousands. The success and scale of Gaddafi’s repression do not for a second decide our opposition to it. But they are crucial to Gilbert’s test for whether we should support what the Western powers are doing.

So let’s assume that Juppe, Hague and others were right: Gaddafi was about to win and kill thousands. ”Can anyone claiming to belong to the left just ignore a popular movement’s plea for protection… when the type of protection requested is not one through which control over their country could be exerted?” asks Gilbert.

Up to then, however, the rebels’ requests had been ignored, not by the left, but by those to whom they were addressed. They asked the great powers who now pose as their protectors for access to weapons days into the uprising. They were refused.

At the time, Berlusconi’s Foreign Minister Franco Frattini voiced most clearly the West’s suspicions about the Benghazi rebels: they were an unknown quantity but some were definitely Islamist (he warned ominously of the proclamation of an “Islamic Emirate” on the southern Mediterranean) and a banner opposing Western interference was prominently displayed.

So intelligence had to be gathered (special forces and spies were dispatched), guarantees had to be sought (commitments to Libya’s commercial treaties were swiftly obtained), the picture allowed to clarify and nothing be done which would enable any agency independent from the interests of the Western corporations and states which had got along famously with Gaddafi over the previous 10 years.

The condition that intervention would not amount to exerting control over the country was breached before the words in the U.N. resolution ruling out an occupation were typed up. What else might Sarkozy and Clinton in Paris three days before the U.N. vote have bargained over from a position of strength with the former regime figures who they plucked as representatives of the Benghazi opposition?

Gilbert does not address the baleful effects of the West’s embrace on the opposition itself. Nor does he consider how intervention led by the former North African colonial powers allows Gaddafi, of all people, to wrap himself in the shroud of Omar Mukhtar, the hero of the devastating Libyan war of independence against fascist Italy, thus giving him another weapon to shore up support.

The opposition may well have started as an admixture of forces comparable with the Tunisian and Egyptian movements. But the former regime elements, appointing themselves as leaders, and reliably pro-Western figures have unsurprisingly been promoted as the rebellion becomes more dependent on Western military force.

If war is an extension of political conflict by other means, then military conflict extends its own political logic. In a position of military weakness the Benghazi council has called for greater and greater Western military action.

Rebels complained early on that they were not in a position to call in Western air strikes. They may want U.S., French and British planes to be the opposition air arm, but they are under U.S./NATO command. It calls the shots. It isn’t the rebels’ airforce; they are now more NATO’s ground force.

The Benghazi council has not yet called for ground troops – which are not ruled out by the U.N. resolution – but if a stalemate sets in… what then? Perhaps some more on-the-ground “specialists” to guide in the missiles or some more “advisors” (special forces, ie highly trained killers, are already there)?

Should the left ignore the call for further help, even if a “popular movement” warns of massacres and, as the Pentagon has said, air action alone is not certain to achieve victory on the ground? Shouldn’t we support steps to make the missile strikes more accurate, to reduce “collateral damage”? Wouldn’t it be immoral not to?

Should we seek to expose the insincerity of the West by demanding more militarily action on behalf of the rebels if they don’t succeed quikely? Should we greet any move toward de facto partition with demands that the West “finishes the job” and removes the butcher Gaddafi?

Surely it would be immoral, having prevented the fall of Benghazi, to watch the fighting drag on and Gaddafi remain in control of most of the country? It is the rebels’ requests, after all, which authenticate the moral case for supporting the bombing, according to Gilbert. And they want more bombing.

The war has already gone further than the restricted no-fly-zone Gilbert says it would be immoral to oppose. The U.N. resolution went well beyond that. The opening attacks were not against aircraft but on ground forces and Gaddafi’s compound – they had the coordinates from Ronald Reagan’s assassination attempt in 1986. Given the results of every other Western air war, is there any doubt that the cruise missiles and “smart bombs” have caused civilian casualties? (At the time of writing Western warplanes are fully engaged in bombing Ajdabiya so the rebels can take it.)

Herein lies the essential unreality of Gilbert’s position. He wants to scalpel out from the U.N. resolution and NATO bombing a humanitarian kernel that we must support. We should oppose the rest. We should monitor the course of an inherently chaotic war to ensure that military action doesn’t go beyond the humanitarian aims we have imputed.

But means and ends were always wider. That’s why the vaunted international consensus collapsed within 24 hours. There was no actual demarcation between a supposed humanitarian mission and the wider objectives of the belligerents – especially of Sarkozy and Cameron, who openly proclaimed a doctrine of regime change.

The political futility of Gilbert’s position is apparent when he writes, “… we should definitely demand that bombings stop after Gaddafi’s air means have been neutralised.” The Pentagon declared them neutralised the day before his article appeared, but the bombing continued.

Alternatives to NATO Action

So what is left of the argument that we should have supported a no-fly-zone which was superseded before the Security Council vote? Only that Benghazi was about to fall, there would be a massacre and there was no alternative to supporting Western action which, whatever its wider ambitions and methods, did prevent it. Let’s accept the claim of an imminent massacre and look at whether there was any alternative.

Gilbert dismisses the idea of the rebels arming as impractical: there were only “24 hours” for them to get the weapons and learn to use them. But any impracticality is a result of the political priorities of the Western powers.

For two weeks they refused weapons and imposed an embargo to stop any shipment while they sought guarantees that the Benghazi rebels would not use them against their vested interests in Libya, established under Gaddafi over the last decade. They blackmailed the genuinely revolutionary elements and suborned others of the Benghazi leadership as Gaddafi’s armour moved in. The left everywhere should say so clearly, not accept the fait accompli of coercion.

Gilbert argues that the left could oppose war against Serbia and Iraq because we were able to point to diplomatic alternatives, but that over Libya there were none. Now, I don’t know how realistic Vladimir Putin’s diplomacy was in relation to Slobodan Milosevic or how credible was Saddam Hussein’s offer to withdraw from Kuwait. But neither do I remember those being necessary conditions for the movements against the wars of 1991 and 1999.

Following Gilbert’s thesis nonetheless, there was a high level African Union delegation on its way to Tripoli to seek a diplomatic settlement when the Western bombing started. Gilbert suggests that Gaddafi is too irrational to be a party to a mediated solution. But we were told that Milosevic and Saddam were also mad dogs, genocidal dictators who would never accept a mediated solution. These are hardly strong grounds for opposing the Balkan and Iraq wars yet giving the West the benefit of the doubt over Libya.

Gilbert argues that any Arab-organised intervention would cause just as many civilian casualties and lead to just as much imperialist influence over Libya. He cites Saudi Arabia and Egypt as two possible interveners. A few moments’ factual assessment shows that such an intervention would likely open up very different possibilities.

It was almost certainly impossible for Saudi Arabia to lead an intervention perceived as supporting the Arab revolution. It was leading the suppression of the revolution in Bahrain at the same time. It is the most brittle and ancient of anciens regimes, which has rejected all calls for it to broaden its social base through serious reform. The tensions would have exposed it utterly and opened a breach for the Saudi opposition movement – much more so than in tiny Qatar. That’s why the House of Saud voted for the West to do it.

Egypt is different. Mubarak is gone. The army remains. But it presides over a society in which an actual revolution is still being fought out. It’s currently Washington’s biggest regional concern. An intervention led by Egypt would not have simply been a cat’s paw of London, Paris and Washington. Its reflex within Egypt would not have been of the “bomb the new Hitler” variety that is dredged up on these occasions in the imperialist countries. It would have been conditioned by the new found activism of the Egyptian people.

Egyptian socialists have issued a statement opposing the West’s military action in Libya and agitating for popular pressure to come to the aid of the rebellion in their western neighbour. You only have to picture Egyptian flags, of the kind that fluttered in Tahrir Square, being waved in Benghazi rather than the Tricolor and Union Jack to appreciate what the difference would be.

There were alternatives to supporting the West’s bombing. Of course, they were not ones Sarkozy, Cameron and Obama would freely choose. They had to be argued and fought for against the line of the Western governments. In that sense they were not as immediate as the willing decisions of those who control powerful states. But if the left were to accept that the only realistic solutions are those that the U.S., EU and NATO want to entertain, then we too succumb to blackmail and there seems little point in building an independent left. We face strategic choices.

Democracy and the Islamist Scarecrow

The left wing of the Egyptian revolution – the most important in the region thus far – has rejected that blackmail. They are not people who can be dismissed as armchair critics sitting in comfort. And the mass forces that were ranged against Mubarak remain independent of Western tutelage.

Gilbert, however, privileges the Libyan rebels, who are now dependent on Paris and London, acting on Washington’s dime – Pentagon spending was 50 per cent of the NATO total 10 years ago, now it is 75 per cent.

In a deeply worrying aside, he asserts that whatever regime the Libyan rebels might form now would automatically be better than “the fundamentalist Muslim Brotherhood” playing a “crucial role” in post-Mubarak Egypt. That makes a terrible concession not merely to the Western powers’ military action, but to their politics and ideology as they try to reshape the Arab region under rejuvenated hegemony.

They want the public East and West to believe that regimes dependent on Western force of arms and constructed at conferences in Paris or London – like Nouri Al-Maliki’s in Iraq – are a priori better than long suppressed Islamic movements playing an independent, prominent role. The Arabs, they maintain, are not ready for unguided democracy. Israel’s Tzipi Livni is promulgating bespoke criteria for Arab parties to be admitted to the democratic club; they include recognising Israel.

The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood does not fit the Islamophobic demonology and in any case is an organic part of Egyptian society – a vital point for anyone who truly believes in national self-determination. As the political space has opened up so have the divisions in an organisation that was always more of a coalition than a monolithic party. There is a widening crack between a politically conservative old guard and a youth imbued with revolutionary aspirations. In fact, several parties look set to emerge from the Brotherhood’s ranks. They include those who emphasise radical democratic and social change as opposed to the imposition of restrictive mores.

The most popular model among the mainstream of the Brotherhood and among many other Islamists in the region is now the AKP government in Turkey. It is far from a socialist administration. But it beggars belief that on account of its Islamic roots it and those who emulate it must be by definition worse than the forces who hope to come to power in Libya under Western bombs and licence.

The Turkish government’s position over Libya is to call for Gaddafi to go, to limit action strictly to humanitarian objectives, to criticise military “excesses” and to oppose Western politicking. In those respects, it’s a position not unlike Gilbert’s. But he cedes the pass to those who are waving the Islamist scarecrow.

Events since the appearance of Gilbert’s article have made bald assertions of the superior progressive credentials of the now Western-dependent opposition in Benghazi untenable. Serious media organisations such as the Los Angeles Times – not conspiracist supporters of Gaddafi – have carried first hand reports of grizzly treatment of black migrant workers at the hands of Benghazi’s new security section. They are also rounding up those they say are “Gaddafi loyalists.” What fate lies in store?

We have been here before. We have seen other sectional movements prove incapable of transcending the divisions fostered or exploited by the regime they oppose, and thus failing to unite the bulk of society behind them. We have seen how in a bitter military conflict some have ended up playing on those divisions themselves. Some have even taken a portion of the brutality they have faced and hurled it back in kind.

In Benghazi under Western oversight we are not seeing the kind of sloughing off of the muck of ages that lit up Cairo’s Tahrir Square when Muslims and Christians linked arms against divide and rule and pressed the most radical revolutionary path.

For several reasons, among them Gaddafi’s repression, that process was marginal to the Libyan uprising. The Western powers certainly do not want to see it emerge now in Benghazi, or in Tripoli if Gaddafi falls. They won’t want the voices in Misrata that are skeptical of the West’s role to grow louder. And they are now in a stronger position to stop all that happening.

Imperial Hypocrisies

Gilbert, of course, points out U.S. and European hypocrisies. The apparent contradiction on which the hypocrisy rests is not incidental. It is rooted in a consistent set of deep interests which are far from contradictory: their hands on the spigot of the world’s energy economy against competitors from without and the mass of the people within.

But with Libya as his point of departure Gilbert’s resolution of the seeming inconsistencies of the West takes us in exactly the wrong direction. If followed, it would lead to a strategic divergence on the left and inadvertent relief to the hypocrites.

Gilbert spells out his approach by pondering the prospect of major Israeli air strikes against Gaza and a hypothetical call for a Western no-fly-zone in response: “Pickets should be organized at the U.N. in New York demanding it. We should all be prepared to do so, with now a powerful argument” – the argument that you did it over Libya so do it over Gaza.

In fact, while the deputy prime minister of Israel has mooted an imminent repeat of Operation Cast Lead, more limited air strikes are already happening, and more intensely than at any time in the last two years.

So this isn’t a question for the future. It is now. What is the response, and what ought it be?

In the region, the reaction among the left and progressives has been overwhelmingly to point to continuing Western – crucially U.S. – backing for the state of Israel, the latest egregious example being yet another U.S. veto of a Security Council resolution opposing illegal settlement building.

It’s been to highlight Tel Aviv’s request for a further $20-billion subvention from Washington. It has been to focus attention on the transitional government in Egypt to demand it reflect popular sentiment, break fully with the Mubarak/Sadat years, open the Rafah border, cut off gas supplies to Israel and declare for the Palestinian struggle. (It has already felt sufficient pressure to caution Israel against an all-out Gaza war.)

Similar arguments are being raised by the radical left and the now considerable pro-Palestinian movement in Europe and the United States.

Their direction of travel is not for further Western military engagement in the Middle East following Libya – intervention that may come in Syria if events follow a similar pattern. It is for ending that engagement – direct and through Western support for the military machines of Israel and Saudi Arabia.

It is not to demand European and U.S. diplomats descend in greater number to “help” bring peace and justice. It is to tell the likes of latter day Prince Metternich, the State Department’s Jeffrey Feldman, to get back to Washington and take with him his schemes for manipulating opposition forces which he perfected in the sectarian labyrinth of Lebanon.

It is not for the West to do more; it is for them to stop doing what they are doing.

This isn’t a semantic game. The movement that emerged in Tunis and Cairo shows the potential for a new agency in the Arab region – a radical force that is independent of elites, big and small, Western and domestic.

Sidi Bouzid and Tahrir Square restored Arabs themselves as the agents of progress in their region after the catastrophe of the neocon experiment with Iraq and all that went before. The West wants to reinsert itself, forcibly if necessary, as the principal actor, the arbiter of progress for the natives.

It might be objected that it is an uphill struggle for popular Arab movements to force a retreat in Western policy, and to frustrate their and the regional rulers’ interests. That’s true.

But it is far more preferable, and infinitely more realistic, than lobbying for the imperial powers to become something which they cannot be: a force for progress, if only they could be persuaded to resolve their supposed mixed motives and conflicted thinking in the right way.

This strategic choice is being fought out now in Yemen. The most dynamic elements in the society – the young people who gather outside Sanaa’s university – are choosing the Cairo of Tahrir Square over the Benghazi of Western suzerainty. But there are other powerful, sectarian or sectional political actors too. Some toy with Western or Saudi backing to compensate for a failure to pull decisive force behind their own bids to be the replacement for Saleh’s regime.

A similar political battle is starting in Syria, where the West does have a vital interest in toppling the regime – but not for one that would be even more of a problem for it and Israel. It doesn’t want a Tahrir Square in Damascus; it would like a Benghazi or Baghdad – and it will act accordingly.

The first phase of the Arab rising of 2011 carried echoes of the European revolutions of 1848. They made flesh the truly progressive modern force which Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels identified in the Communist Manifesto published that year as “the independent movement of the immense majority, in the interest of the immense majority.”

Such independence in the matured global capitalist system of today depends upon many things. Above all it cannot happen without spurning the embrace of the biggest capitalist powers and consistently opposing their ideologies, their political machinations and their killing machines. •

Kevin Ovenden is a member of the executive of the Respect Party, and leader of Viva Palestina. This article was first published on the socialistunity.com website.

Resources:

- More left views on Libya at the Links website.