From the Protests to Palestine: The Far Right in Israel and the Left

Benjamin Netanyahu returned to the Israeli prime minister’s office in November, backed by a coalition of religious and far-right ethno-nationalist parties. Since then, clashes between Israeli armed forces and Palestinians have escalated, due largely to increasing raids on Palestinian civilians and highly provocative armed aggression by Israel at the al-Aqsa Mosque. Netanyahu’s government is additionally attempting to consolidate its control over the judiciary by claiming the right to appoint judges and constrain the courts’ jurisdiction – a move that has sparked massive protests across the country. On March 10, the Socialist Project discussed these developments with Avishai Ehrlich.

Ehrlich has been active in the anti-Zionist Left in Israel since 1963. He is a former professor of Political Sociology specializing in comparative protracted conflicts at the Academic College of Tel Aviv-Jaffa. He has also taught at Middlesex University in London, York University in Toronto, Tel Aviv University, and the University of Nicosia. He has been one of the editors of Khamsin: Journal of the Revolutionary Left of the Middle East and a contributor to Socialist Register and Monthly Review.

Ehrlich was interviewed by Donald Swartz, retired Professor of Public Administration at Carleton University, a member of Free Transit Ottawa, and co-author of the new edition of From Consent to Coercion: The Continuing Assault on Labour (UofT Press, 2023). Editorial assistance from Niko Block.

Donald Swartz (DS): Give us some perspective on the current upsurge in violence and what seems to be behind it.

Avishai Ehrlich (AE): The situation from the point of view of Palestinians is desperate. They’re completely dependent on servicing and working in the Israeli economy. In Gaza, the situation is much poorer, it’s closed, it’s encircled. They can go out and work now more than in the last few years and they get money from the Emirates on condition that they stay more or less quiet. In the West Bank, you have the Palestinian Authority, which is completely corrupt, with the old head of the Authority Abu Mazen who has worked with the Israelis.

But the resistance today to the Israelis is not organized; it comes from localities of young people, and most of the attempts of resistance are individuals. Many of them are very young people, I’m talking thirteen, fifteen, sixteen. They find weapons. If they don’t, they take a knife. They go out, they know they’re going to be killed. Yesterday, a young Palestinian tried, he was killed within two minutes. He managed to hit two people before he was hit himself.

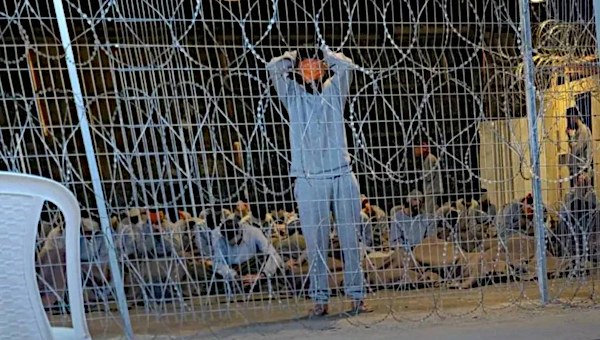

With the possibility of this thing getting more organized, the Israelis are keeping up the pressure. This means that groups of civilian-dressed soldiers infiltrate into Palestinian refugee camps on the basis of gathering information on youngsters. They search and seize them.

That means that every night you have raids in many Palestinian villages. Sometimes they come in trucks bringing commercial things to the shops, but inside are fifteen soldiers, special units. They stop at the place where they want to seize some people, burst out of this truck into the house, kidnap the people. In most cases, it ends with a shootout.

DS: We’re wondering about the aggression of the settlers in the West Bank: is it indicative of some kind of strategy to foment clashes that will justify the occupation? Are they pawns in this in some way?

AE: There is a whole ideology. The ideology is basically God has given us this land, and we’ve come back to settle it. And these people seriously believe in it.

In the past, even Netanyahu, when he had to justify his policies in the United States, still stuck to the formula of two states, which kept at least a horizon of a certain solution. This, in the new government since November, has been completely dropped. There is no talk anymore about the solution.

The settlers are trying to take over the security establishment, and the minister of internal defense is trying to build a militia, an American type of national guard, alongside the police and border police, to challenge the army. And the army kind of tries to keep, with the courts, keep some law and order or at least a semblance of law and order.

Netanyahu has now formed the government with the Likud as the biggest party, alongside the ultraorthodox national religious parties, which are the settlers’ parties, and alongside a party which for many years was ostracized as a terrorist group, the Kahana Jewish Defense League [or Otzma Yehudit]. Now they are a party, they have seven members in government, and they are part of the coalition. So, the coalition is right, extreme right, and religious right. And within this new government, the Likud is completely subdued and does only what Netanyahu wants them to do. There is no real discussion; he is like a dictator within the party.

The other active part of the coalition is the ultra-orthodox. They have a completely different agenda. They do not really accept secular Zionism. They have built an alternative to secular society; we call it the society of the yeshivot. Most of the male offspring study all their lives. They do not serve in the army, and the rate of participation in the labour force is much lower than in the rest of the population, which means they’ve created a dependent society with low income and a very high rate of birth, about three times the rate of the other sectors. And most of them are dependent on subsidies from the state.

The low participation in the labour force has to do with the fact that they have an educational system which does not teach math or English. They only concentrate on what they call religious studies, so the men are not capable of really joining the labour force. They keep them in dependence to the age of 50 or 60 on a very small stipend every month. So, this is the kind of society that needs the state in order to keep this way of life.

DS: In your correspondence with me, you were talking about some of the early demonstrations against the government and then made some reference to how the protests are being taken over by different groups, more mainstream groups. Can you talk about the initial opposition and how it’s evolved?

AE: The protest officially is about the changes that the government wants to bring in on the legal system. We have no constitution, and the High Court had relatively a lot of power. It’s easier to launch an appeal to the court than in most European countries. And the court is the “wise” arm of the state. I mean I’m the last one who thinks that the court is neutral; the court is Zionist. The High Court was involved in a military government ruling over Arabs. The High Court has made it possible to take land from Palestinians and pass it to the settlements. The High Court was responsible for justifying a lot of war crimes. But the High Court was autonomous.

This is a thorn in the side of both the religious parties and has become a thorn in Netanyahu’s side. For the religious parties, they do not recognize secular law. The secular law of the state of Israel is an alternative to the rabbinical leadership and to Jewish religious laws about marriage, funerals, and things like this. The law in Israel pays lip service to Jewish scriptures but basically is a secular law. There is abortion, there is acceptance of gay marriage. It’s a fairly liberal kind of law. And this was achieved without the constitution.

Now, for the last three years, Netanyahu has been charged with corruption. He wants now to change the whole structure of the courts, especially the selection of judges and to make the selection of judges completely political. In other words, people say he will choose the judges who will sit in his trial. But it’s more than just him. He wants to make the whole thing dependent on the government. And the government will also make the rules about what the court can intervene in or not.

That has been the official reason for the protests, to oppose the politicization of the juridical system. The main slogan is, there is no democracy without separation of judicial, government, and parliamentary powers.

But there are other reasons. Most of these people served in the army. As long as Israel is seen as a democracy among Western countries as well as the United States, there is an agreement that in cases of war – or especially about the behaviour of the army – the Israeli system is free and can investigate and bring to charge anyone who abrogates the laws, including human rights. So, one of the main shields against dragging Israel to the Hague and the international court of justice was the Israeli legal system. And what a lot of people think is that the changes will bring inevitably a lot of people to the court in Hague, and they will be charged. This is why, among other things, military elites like pilots and intelligence units are at the spearhead of these demonstrations.

So, what you have here is a protest which to start with seems to have nothing to do with the left. But it became the largest protest in the last ten or fifteen years – I would say the largest that Israel has known since its inception.

However, as my Palestinian friend said, “How can you participate in the demonstration where everyone goes with the big Israel flag? To me it looks like a fascist demonstration.” So, I had to engage with him about the meaning of the flag in these demonstrations. The flag is being contested in Israel. The right-wingers claim that the ones who defend the High Court are basically hidden leftists, hidden traitors. There is a contestation of belonging in the community. As a sociologist, I can call it the sociology of belonging. The contest over the flag is a contest over who belongs, and who is not a patriot. Again, that does not belong to the left, especially not to the anti-Zionist left.

But the Israeli Arabs are twenty percent of the citizens of Israel. And they are in Parliament; they have three political parties, and they are politically essential in creating the possibility of a non-insane non-settler coalition. So, the demonstrators started by calling the Arab population to demonstrate. The Arab population said we do not want to demonstrate under this flag, we want to bring Palestinian flags. Palestinian flags in a demonstration alongside all these Israeli flags with all of the people who really are avid volunteers in military units – it doesn’t go together. On the other hand, a lot of Arabs did not want to come without the flags. The result is that the Arab participation in this protest movement is limited.

DS: Can you reflect on the weakening of the Israeli left? What remains of it?

AE: The term left is not used very systematically in Israel and does not mean the same thing outside as inside Israel. In Israel, the key thing of left and right is vis-à-vis the Palestinian question. Outside of Israel, left and right is basically about the economy and the kind of social regime: involvement of government privatization, capitalism, and so on. We do not really have, apart from a small Communist Party, we don’t have any more a labour movement. The Labour Party has four members in Parliament, and the Labour Party is not pro-labour. The result is that it’s not a party that people regard as an alternative.

To the left of the Labour Party is the Meretz Party, which was sort of an offshoot of Mapan, or Hashomir Hazair, which has become a liberal party. It is not social democratic anymore.

I would say that the Communist Party veers between social democracy or Eurocommunism to a tiny group of Stalinists.

But apart from this, on the parliamentary level there is no Left left. The Meretz party attracts some gays, feminists, but has no meaningful attitude toward the welfare state or social democracy. So, the Left has died a long time ago.

Let me say more about the Communist Party. The Communist Party is basically an Israeli-Palestinian party. It has between four and five members in Parliament; it is itself a coalition of forces which are not socialist but which at least are secular and not particularly nationalist. It pays lip service to questions of minimum wage and union stuff, but that’s about it. It stands for the two-state solution. But the party is ninety-eight percent Arab. The number of Jews in the party, I would say, is at most three thousand. So, when you’re talking about how many people are non-Zionists, we’re talking about these kinds of numbers, a few thousand, less than my five fingers.

What we do within the marches is that the so-called left has opted for demonstrating within the demonstration. The demonstrations usually gather on late Saturday afternoon, and there is a central place where people speak. And the left has created a kind of focus area, where there are red flags, there are lots of posters distributed and carried which have to do with the conflict, with “there is no democracy with occupation,” so the common theme is democracy. So, doctors come and they say there is no health without democracy. Students come and they say there is no academia without democracy. And we say there is no democracy with occupation.

A lot of people on the left said we don’t know if we should be there, it has nothing to do with us. I say, look, we don’t know how it’s developing. It’s not an event, it’s a process. A process has no ending. The point is to be there, to have material, and try to call up meetings and invite people to come.

DS: Within the West Bank, the people that are that are pushing the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) strategy are secular and are pushing the issue of rights, equal rights. Given what you’re describing, with the democracy themes within the protests in Israel, is this not a vehicle through which more Palestinians could be brought into a movement for equality?

AE: In theory, yes. In practice, the people who are secular and doing BDS are not doing at the same time violence, or bombs, or whatever. It can’t go together. Either we fight or we do BDS. I’m not blaming the Palestinians. I mean, I said many times to my Palestinian friends, if I was a Palestinian, I would do exactly as you do. So, it doesn’t come as criticism, even against armed struggle. I can see why it’s necessary. I’m not a pacifist, but you can’t have both things.

And even BDS has been presented, like every criticism of Israel, as being anti-Semitic. In the demonstrations, the BDSers will not have a great success. If it would have success among the non-Zionist left is irrelevant. Can the BDS make inroads into the Israeli mainstream? At the moment, no.

The question is, will the United States or the Europeans go heavier on an Israeli government or prevent a more authoritarian approach to Palestinians? I doubt it. If they do not do it, can BDS do it? I’m not sure. I don’t think so. That doesn’t mean that the BDS should stop working where it can and do what it can in the countries that it can. •