Bring Politics Back Into Society: 40% Abstained – Not Without Justification

What we had long expected to occur has happened: in Italy, where antifascism is written into the Constitution, Fratelli d’Italia, the party of Giorgia Meloni, has won – Meloni who does not call herself a fascist because doing so would be illegal but loses no opportunity to show that she is one.

This is not through her party symbol, which is intentionally dominated by the historic tricolour flame, but through the ties she repeatedly emphasises with all similar organizations circulating in Europe, from that of Marine Le Pen to Spain’s VOX, to the Hungarian and Polish governments. While the total votes of the right have not increased, it is still dangerous that Meloni absorbed almost five million votes of those who only five years ago had voted for Lega (the League) or Silvio Berlusconi, both of whose forces have by now become marginal.

Meloni has now won, and President Sergio Mattarella is obliged to entrust her with the task of forming the next government, whose policies, however, will not be, in substance, very different from Mario Draghi’s. Neoliberal globalization is no longer a choice that national governments can make; it has long been installed by the major financial groups on the international market; the national governments can only decide on details. Meloni has, in any case, already declared her fidelity to NATO, and Draghi is now working with her to get the best out of the EU. She will also try to make people believe that there has been a political turn. Worst of all, her government will have an impact in the areas of civil rights, the persecution of immigrants, women’s rights, abortion, the rights of LBGQTs, education, etc.

Contempt for Democracy

But the most worrisome aspect is the contempt for democracy, the illusion conveyed to the system’s victims that if the ‘chatter’ of politics is eliminated and we put our trust in a strong hand, all problems will be solved.

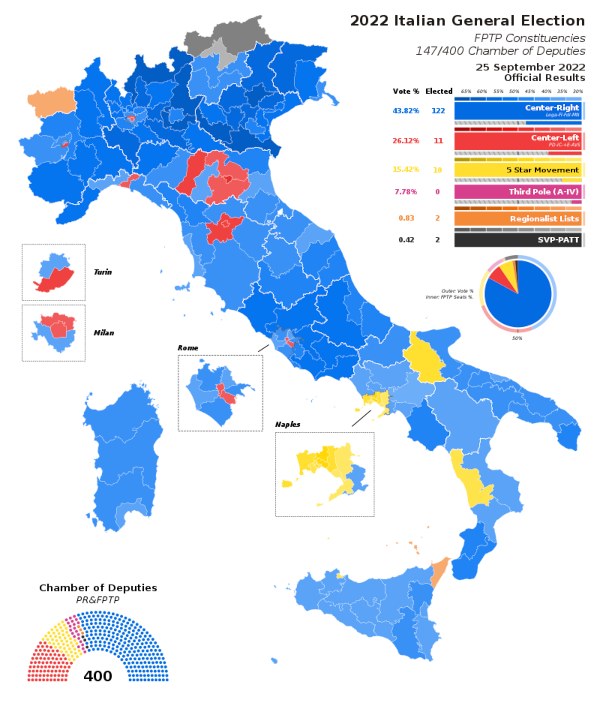

I am emphasising this aspect of our future government because we cannot explain the thinking of Italians if we focus only on traditional antifascism, neglecting the class core of the current political context. This is an error made in the electoral campaign of the Partito Democratico (PD) (which was the real loser, leading to Letta’s announcement that he will step down). It was a stance taken out of concern to not frighten the centrist groups with whom it sought to ally itself up to the end. The result was a break from the Five-Star Movement, which, by contrast, recouped a large part of its large electorate of five years ago, reaching third place at 15.3%, just a little below the PD. It won especially in the South, on the basis of its good social programme. In recent years, this movement, born as a protest ‘against politics’, defining itself as ‘neither right nor left’, would end up governing with all forces, but it passed through a tormenting experience, which led to its maturing and the marginalization of its more ambiguous wing. Today, it is clearly aligned – although with a culture that is certainly not a traditional left one – with our front. It is no accident that it garnered a great many votes from those who wanted to condemn the PD’s choice to exclude them from the ‘broad antifascist front’.

Reconstruction of the Italian Left

Above all, there is now an urgent, and also a possibly attainable, goal: the reconstruction of the Italian left. The most significant statistic of these elections, to which no one has paid attention, is that almost 40% of Italians (9% more than the last time) did not go to the polls, especially young people. Not because they are depoliticized but because they are not interested in an institutional political debate so distant from what they consider to be important: the epochal looming historical change due to the ecological threat,with which no minister is occupied. (It has been calculated that only 0.5% of the time taken by election campaign speeches was devoted to this issue.)

Reconstructing the Italian left is possible, but it is something that will take a long time, and it does not consist in copying the ‘Mélenchonian’ project because it is not enough to put together little pieces of defeated parties as was done in France. (Would it have been possible if France had not experienced the ambiguous but powerful jolt of the Yellow Vests rebellion?) It is possible to relaunch a left, even bringing with it a part of the cultural heritage and experience that ought not to be discarded. But it has to start from society, reconstructing a network of communities and projects, not pretending that we can return to the great post-war years when the social compromise was possible that allowed a relative redistribution of resources and important reforms but which by now have eroded everywhere (as in Sweden). Now, either we confront the very core of our system of producing, consuming, and living – requiring a real revolution – or the road will be open to the violence inevitably produced by unsustainable injustice. This is the main ground on which we will have to fight. The 18 MPs and senators we now have through the Verdi-Sinistra Italiana list will certainly help us, but the main task is to reconquer society.

Unione Popolare (composed of Rifondazione Comunista, Potere al Popolo, DemA, Manifesta, and other groups) did not manage to enter Parliament, as was predictable due to the terrible electoral law that has made so-called technical alliances necessary. (Sometimes one has to accept a small compromise, one which in this election was worth the effort, as it has not required of Sinistra Italiana any political concession. Otherwise, the left would have completely disappeared from Parliament, which would have had a very negative symbolic impact.)

The ‘obligatory revolution’ now on the agenda is called ‘degrowth’ – which is not, as our dinosaurs would have us believe, a return to a Middle Ages of austerity but, rather, the conquest of a different kind of happiness. (A professor at the University of Tokyo has recently published a book entitled Capital in the Anthropocene, which speaks precisely of what happiness might be that is not based on the obsessive consumption of superfluous commodities. It became a bestseller in Japan, breaking all records with 500,000 copies sold. A poll has shown that nearly all its readers are young people.) •

This article first published on the transform! europe website.