Leo Panitch’s Many Lessons on Living Under American Empire

Leo Panitch’s untimely death last weekend is a tragic loss for the international left. His intellectual and political contributions toward rebuilding working class movements in such diverse settings as North America, the UK and Greece were consistently lucid, incisive and trenchant – that is, indispensable. They reflect an internationalist commitment to concrete struggles for democratic socialism from a strategic standpoint, always mindful of capital’s pervasive power across the planet, particularly after the demise of the Soviet bloc.

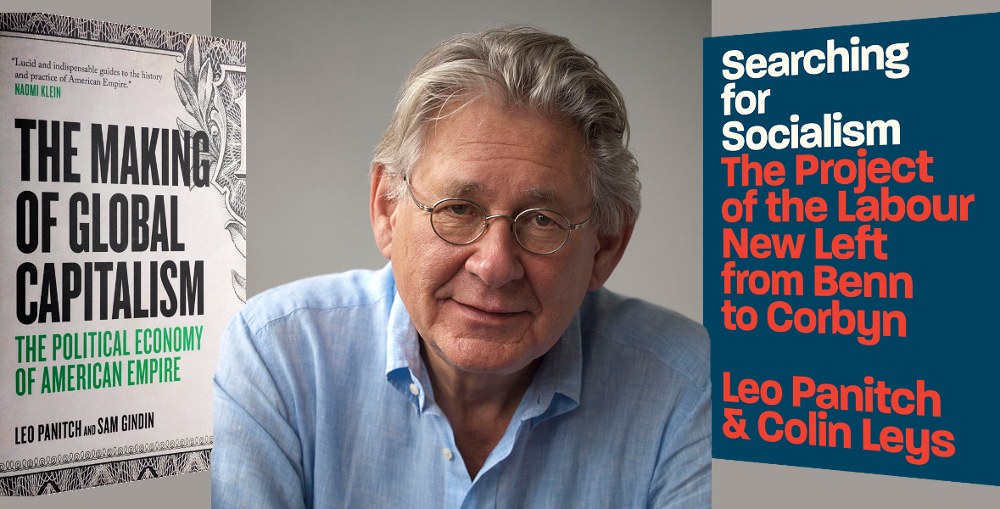

Others will write about Leo’s life-long involvement with the UK Labour Party, both as an active participant and academic observer of the Bennite left – not least in his latest book Searching for Socialism written with Colin Leys. These assessments were shaped by Ralph Miliband and Nicos Poulantzas’ theories of class power and the capitalist state, but from the 1990s Leo also reformulated and upscaled these concepts when applying them to the analysis of global capitalism. Through his collaborative work in editing the annual Socialist Register, and culminating in the prize-winning book on the political economy of the American Empire (co-authored with Sam Gindin), Leo provided invaluable insights into the dynamics of the contemporary international system.

Foremost among these was the insistence that globalization is authored by states. In a variation of Karl Polanyi’s paradoxical dictum that ‘laissez-faire was planned’ under the nineteenth-century free-trade Pax Britannica, Panitch and Gindin demonstrated how neoliberal globalization was the product of a state-sponsored re-regulation of markets across the world in favour of the capitalist class through privatizations, labour reforms, union-busting legislation, fiscal discipline, trade and financial liberalization, and so forth.

The Role of Capitalist States

Like other anglophone Marxists radicalized by 1968 – David Harvey, Peter Gowan, and in a different way, Paul Hirst – Panitch cautioned against underplaying the role of capitalist states in managing the common affairs of the global bourgeoisie. Against the then vogueish invocations of a post-national, decentralized, rhizomatic Empire, Panitch (on international matters almost always now writing with Gindin) kept reminding us that national institutions like central banks, ministries or departments of trade and finance, and their accompanying regulatory bodies were critical to the proper understanding of global capitalism. It was also imperative to register that some states – the USA, principally – were far more powerful than others.

Their injunction might be summarized thus: ‘follow the memo’. Marxist critics of global capitalism should trace the changes and continuities among top staffers and take seriously the sometimes conflicting policy positions of leading state – and indeed multilateral – functionaries. This seemingly uncontroversial recommendation runs contrary to the more ‘structuralist’ views of state power, particularly with regard to American foreign policy, where policymakers are seen to have limited autonomy and external relations appear instead constantly and consistently to be driven by Washington’s manifest imperial destiny.

Capitalist states are certainly conditioned to facilitate the smoothest possible transnational reproduction of profitable markets, but this can take very different forms, subject to internal and external constraints and contingencies. Newly industrializing nations like America, Japan and Germany generated inter-imperialist rivalry at the end of the nineteenth century, leading to World War I, while the ‘unipolar moment’ immediately after the Cold War offered unique opportunities for the consolidation of neoliberal globalization.

Experiments in post-war reconstruction serve, for Panitch and Gindin, as especially powerful instances of planning and coordinating efforts attached to the successful reproduction of global capitalism. Drawing on historians of the Marshall Plan like Michael Hogan, and inspired by Antonio Gramsci’s prescient essay on ‘Americanism and Fordism’, Panitch and Gindin underline how capital is above all a social as well as a productive force – especially when it is imposed from the outside.

War-time planning during the 1940s by a newly-emerging American security state for a post-war Washington-led international order lay at the heart of the European Recovery Program. But the ‘New Deal synthesis’ of growth, productivity, and redistributive stability it promised was also reliant on the fear of Soviet communism driving sufficient elements of the European working classes into an ‘American way of life’.

The coordinating role of the American state in generating economic integration among capitalist ruling classes – and indeed incorporating subaltern classes into the western alliance – was combined with the social power of a Fordist regime that fuelled not just consumption-driven production, but also its attendant cultural forms. Whether in Dagenham or Yokohama, Miles Davis was as much a part of American hegemony as the Ford Escort (or Mazda).

Post-Cold War Capitalism

The lessons of all this for the contemporary, post-Cold War period are threefold. First, reports announcing the death of global American hegemony were – and continue to be – grossly exaggerated. As might be expected from a global capitalist system, the US has competing economies and regionally contending states in the People’s Republic of China and Russia, but this is not tantamount to a nineteenth-century inter-imperial rivalry, nor a new global Cold War. Like any other major capitalist state, China is pursuing international influence and economic gain as a partial power. It will go to war over Taiwan and Hong Kong, and will use the Belt and Road Initiative to further integrate its domestic market, as well as export surplus capital and secure lines of communication and trading partners across Eurasia and beyond.

None of this even comes close to replacing the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency; challenging America’s status as the world’s principal destination for foreign direct investment in value terms; Washington’s dominance over the major international financial institutions; let alone its dwarfing of Chinese military power with hundreds of installations across all the world’s continents, and fleets patrolling the planet’s oceans.

“Progressives seem to believe,” Panitch and Gindin argued in 2013, “that to shout American decline from the rooftops de-legitimates the system.” But in fact, it can simply reinforce the ruling class’s resolve to reverse perceived decline and, more damagingly, distract the left from the real political challenges in transcending global capitalism through democratic mobilization, rather than waiting for irresolvable internal contradictions to play themselves out.

Here a second key insight becomes apparent, namely the historical particularity of an American Empire that rules through rather than over states. This empire of open doors (free trade) and closed frontiers (formal sovereignty) operates an informal imperialism where, as Marx would have it, “the dull compulsion of economic relations completes the subjection of the labourer to the capitalist.” War, violence, dispossession and oppression have, to be sure, all accompanied capitalist development throughout the centuries, and they are certainly latent to all market exchange. But, like his former colleague at York University in Canada Ellen Meiksins Wood, Leo was also keen to stress how it is the billions of seemingly unremarkable, instrumental, lawful market transactions that take place daily across the world which fundamentally reproduce global capitalism.

This being so, the final lesson derived from Panitch and Gindin’s analysis of global capitalism under American Empire is that class mobilizations in and against the state are critical to any credible strategy of socialist transformation. If class power is reproduced through the social infrastructure of the capitalist state, so too can it be undone by democratizing the immense resources of capital and the state. Anti-imperialism in this sense comes as much from resisting the war-mongering, ecological destruction and transnational super-exploitation emanating from the world’s leading capitalist states, as it involves building alliances within and across those states – including the US, China, Japan and Europe -to radically transform them from within.

Like many militants of his generation, Leo saw socialist strategy in the long duration – as a process full of setbacks, sudden accelerations, unexpected triumphs, and all the doldrums in between. Of his many legacies, both political and intellectual, one that will doubtless persist is Leo’s unique capacity to bridge past and present struggles; connecting older and younger comrades across different parts of the world in focusing on the big prize: the self-emancipation of the working class. •

This article first published on the Labour Hub website.