Somalia, Yemen, Ethiopia: The Wounds of Underdevelopment, Colonialism/Imperialism, and the Cold War

Until the astonishing imperialist assault by the United States on Venezuela and the kidnapping of Nicolás Maduro and his wife, news related to Israel’s recognition of Somaliland, Saudi Arabia’s attack on southern Yemen, and the agreement between Ethiopia and Somaliland on the use of Red Sea ports were among the hot headlines on many global venues. The chaotic and miserable conditions of these three war-torn countries, and the poverty and displacement of these ancient nations, are the direct result of internal underdevelopment, colonial and imperialist interventions, and competition among major foreign powers. Moreover, for those sympathetic to the former Soviet Union, these three countries were once prominent examples of the “non-capitalist path of development” or a “socialist orientation.”

A very brief and rapid glance at these painful pasts may help shed light on today’s situation, in which all three countries, to varying degrees, are “failed states” and, aside from the great powers, are exposed to conflicts involving emerging regional actors.

Historical Background and Imperialist Rivalries

Yemen and Somalia, traditional tribal societies that have been influenced by the spread of Islam in the region since the seventh century CE, converted to Islam in various ways, giving rise to different local sheikhdoms. Later, during the colonial rivalries of the nineteenth century, foreign powers entered the region not only to exploit natural resources – including Britain’s export of Yemeni coffee (oil had not yet been discovered in Yemen) – but primarily to gain access to the strategic Red Sea passage on both sides of the Gulf of Oman: one in the south of the Arabian Peninsula and the other in the Horn of Africa (Map No. 1). This route had gained extraordinary importance after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

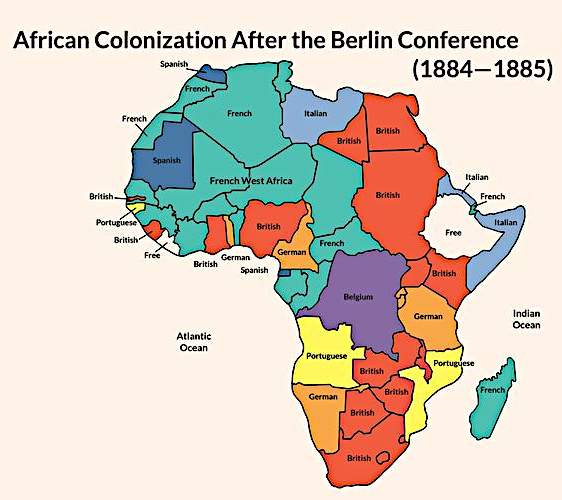

Ethiopia, which at that time possessed a long coastline along the Red Sea, also had distinctive characteristics as a predominantly Christian country and one of the oldest monarchical systems in the world. With the formal partition of Africa among European colonial powers at the disgraceful Berlin Conference of 1884, Ethiopia was the only country in East Africa that was not handed over to the colonizers and did not fall under colonial occupation (Map No. 2). In 1895, Italy invaded Ethiopia but soon encountered resistance and retreated to Eritrea, where it remained. Later, in 1935, during the fascist era, Italy once again occupied Ethiopia. Ethiopian resistance forces, with the assistance of Britain, expelled Italy from Ethiopia, and Emperor Haile Selassie returned to the country. In 1952, with the support of the United Nations, the groundwork was laid for the union of Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Somalia, until the Middle Ages, lacked a central government and consisted of several sultanates. For a period, it came under Ethiopian control; however, resistance by the Somali people put an end to this domination. Portugal also attempted to occupy Somalia but was forced to withdraw due to popular resistance. Under Europe’s colonial design, Somalia was assigned to Italy. At the same time, a small but strategic area – located between Somaliland in the north and Ethiopia’s Eritrean region at the narrow entrance to the Red Sea, Bab el-Mandeb – was given to France. Until independence in the 1960s, this territory was known as “French Somaliland,” later becoming the small country of Djibouti. Today, it hosts foreign bases – not only French, but also American, Chinese, Japanese, and Italian (Map No. 3). In 1888, Britain took control of northern Somalia as “British Somaliland,” while Italy established “Italian Somaliland” in the south. Muslims, led by a cleric, Sayyid Muhammad Abdullah, who had founded the Dervish movement and whom the British derisively called the “Mad Mullah,” resisted the British Empire for twenty years. During World War II, Italy occupied British Somaliland, but in 1941, Britain took control of Italian Somaliland. In 1960, both Somali regions were united and gained independence as the “Somali Republic.”

Yemen, with its ancient history, in the modern era initially came under the control of the Ottoman Empire but soon faced popular uprisings. In the early seventeenth century, the British Empire established a trading post in Mocha on the Red Sea coast for the commerce of Yemen’s famous coffee, and as the strategic importance of the Red Sea increased, Britain expanded its influence in southern Yemen. Competition and conflict among the Ottomans, Egypt, and Britain continued. In 1914, the Anglo-Ottoman Treaty delineated spheres of influence, in effect laying the groundwork for the later division of Yemen into northern and southern regions. With the outbreak of World War I, Ottoman influence disappeared.

With the rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt and the strengthening of Arab nationalism from the 1950s onward, republicanism intensified in opposition to the rule of the Yemeni imams. For a time, Yemen even joined the “United Arab Republic” created by Nasser. In 1962, the Yemeni imam died, and Nasserist officers proclaimed the establishment of the Yemen Arab Republic. A bloody civil war ensued in North Yemen between supporters of the new imam, backed by Saudi Arabia and Britain, and the Nasserist republicans; it ultimately ended in victory for the republicans. Egypt assisted in forming a liberation army and demanded the independence of South Yemen, where various Yemeni tribes were engaged in guerrilla warfare against Britain. Even repeated bombardments by the British Empire failed to defeat them. Finally, with Britain’s withdrawal from the region in 1966, South Yemen achieved independence in 1967, leading to the creation of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen. (One of the reasons Egypt suffered such a rapid defeat in the Six-Day War with Israel was that a portion of its army and resources was tied down in Yemen.)

Military Coups and the “Socialist Orientation”

The 1960s and early 1970s brought major transformations to all three countries – Somalia, Yemen, and Ethiopia. In each of them, military coups were carried out by officers with socialist leanings. The bitter experience of the damage inflicted on their countries by imperialist powers was not without influence on their turn toward socialist ideas and the Soviet Union, especially at the height of the Cold War. All three governments sought to advance socialist policies in their backward, tribal, feudal, and deeply religious societies by copying the Soviet system.

The political systems of all three became one-party regimes under the strict control of the ruling party, its politburo, and the security apparatus, accompanied by repression of opponents. Economically, to varying degrees, they nationalized industries and agricultural land and established cooperatives. They also implemented important reforms aimed at improving the living conditions of low-income groups, promoting gender equality, and expanding health care and education. Taken together, these policies were aligned with the theory of economic and social development known as the “non-capitalist path of development,” later termed the “socialist orientation,” which at the time was widespread among Soviet supporters and fraternal parties, including in our own Iran.

In Somalia, in 1969, following the assassination of the president, the army commander, General Mohamed Siad Barre, came to power through a coup and took control of the country with a military junta known as the “Supreme Revolutionary Council.” He had been trained at a military academy in Italy and had worked in the police and security apparatus during the period of Italian rule in Somalia. He introduced many changes in infrastructure development, the fight against illiteracy, and nationalization.

After several years, he dissolved the Revolutionary Council and established the “Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party as the sole ruling party,” based on “scientific socialism” and “Islamic principles.” As he consolidated his personal power, he sought to annex the scattered Somali-inhabited surrounding regions. One of these regions was Ethiopia’s Ogaden, which he invaded in 1977. Interestingly, at that time, Ethiopia too – as will be discussed – had brought to power a similar Soviet-aligned system.

The Soviet Union attached great importance to both Ethiopia and Somalia because of their strategic locations, and when it failed to prevent war between its two allies, it sided with Ethiopia, which it considered politically closer. Soviet advisers and Cuban troops assisted Ethiopia, and Somalia suffered a severe defeat. Siad Barre, whose position was weakened, expelled all Soviet advisers from Somalia, severed relations with the Eastern Bloc, moved closer to the United States, and, with the rise of Reagan, received substantial US aid.

Gradually, opposition to Siad Barre’s dictatorship intensified, and he escalated repression. Guerrilla warfare by various clans further weakened his regime, and finally, in 1991, he was overthrown and fled to Nigeria. The resulting power vacuum led to Somalia’s civil war and the devastation and chaos that engulfed the country.

In Ethiopia, following a massive famine, mutinies by soldiers combined with the participation of broad segments of society led to a wide-ranging movement with demands, among others, for land reform and the release of political prisoners. In 1974, a military group led by Mengistu Haile Mariam overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie and brought a Soviet-aligned system to power.

Initially, leadership rested with a military junta, but Haile Mariam sidelined the other generals and established his dictatorship through extremely violent repression. During the Ogaden War mentioned above, he became increasingly dependent on the Soviet Union. He pursued policies of nationalizing industry and land and enforcing forced collectivization. In 1984, he founded the “Workers’ Party of Ethiopia” and became its general secretary.

Severe famine intensified social and political problems. Opponents of the regime formed the “Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front.” With the weakening of the Soviet Union and the beginning of its collapse after the Afghanistan war, Soviet aid to the Ethiopian government was cut off, and opposition forces advanced toward the capital. Haile Mariam’s efforts to mobilize the population and students failed, and in 1991, he fled the country for Zimbabwe. He was later sentenced to death in absentia by a court.

In South Yemen, where the “National Liberation Front of Occupied South Yemen” had emerged during the anti-colonial struggle, the Marxist–Leninist wing of the Front ousted the Nasserist president in a military coup in 1969. With the support of the Soviet Union, China, North Korea, and East Germany, it established the “Yemeni Socialist Party.” The one-party system moved toward nationalization of banks and insurance, industry, and land. Important reforms were also implemented regarding women’s rights, including the prohibition of polygamy and child marriage, the introduction of secular education, judicial reforms, and the replacement of sharia law with civil law.

In foreign policy, in addition to supporting the Palestinian movement, South Yemen supported the Dhofar movement in Oman – a conflict in which the Shah of Iran, following the Nixon Doctrine and acting as a proxy for the United States, had entered the war. The Soviet Union also established a naval base in South Yemen for its Indian Ocean fleet. In 1986, a Soviet oil company succeeded in discovering oil in South Yemen. Meanwhile, internal disagreements within the political leadership reached a climax in 1986, and leaders turned their weapons on one another. More radical elements seized control, and civil war broke out. Many people migrated to the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen). With Gorbachev’s rise to power, changes occurred within the party. The two Yemens unified in 1990.

One of the key reasons for Soviet support of the so-called socialist orientation of these three countries was the transformation that had taken place in naval control during that decade. With the death of Gamal Abdel Nasser and the rise of Anwar Sadat in Egypt – and his “rectification” policies – the Soviet Union lost its naval bases in Egypt. More importantly, in 1966 the United States acquired the Diego Garcia archipelago in the middle of the Indian Ocean from Britain, which had deceptively taken it from Mauritius and named it the “British Indian Ocean Territory,” leasing it to the US for fifty years. (In 2019, the International Court of Justice ordered its return to Mauritius, but Britain, with US support, has still ignored the ruling.) By establishing major air, naval, and missile bases on these islands, the United States effectively brought the entire Indian Ocean under its control. The establishment of allied governments in the Horn of Africa and South Yemen could create a balance in control of the region’s seas for the Soviet Union; therefore, it supported regime changes in this region, just as it was simultaneously doing in Afghanistan.

Failed States and New Conflicts

Each of these three countries has undergone many transformations over the past few decades. New civil wars fractured nation-states that had been formed in different ways, and the central governments in these countries – largely except Ethiopia – effectively turned into “failed states.” Poverty and hunger wiped out or displaced large segments of their populations. Religious fundamentalist movements replaced the former national movements.

Following internal conflicts and the collapse of the central government, Somalia was once again fragmented in 1991, and Somaliland in the north unilaterally declared independence. The Civil War disrupted social order, and the country descended into chaos. Thousands of US troops, in connection with a UN peacekeeping mission, entered areas near Mogadishu, but Somali militias attacked them, and many were killed and wounded. US troops withdrew, but clandestine operations by the CIA continued. In 2006, Islamists influenced by al-Qaeda formed the “Islamic Courts Union” in southern Somalia and advanced rapidly. The United States, with the help of Ethiopia and through extensive bombings, suppressed the forces of the Islamic Courts. However, a more dangerous current emerged from within these courts under the name “al-Shabaab,” which had previously served as their military wing. Al-Shabaab continued terrorist operations and sought to impose its desired religious order, and after some time, formally allied itself with al-Qaeda. The United States attempted to halt the advance of the Islamists by uniting Somali tribal leaders. Still, suicide bombings, kidnappings, hostage-taking, and other terrorist operations continued – not only in Somalia but also in neighbouring countries. More importantly, given Somalia’s long coastline, piracy disrupted shipping in the Somali shorelines.

Ethiopia

also experienced fragmentation following the fall of its government in 1991. Eritrea, which encompasses Ethiopia’s entire coastline along the Red Sea, declared independence in 1993 through a UN-supervised referendum, turning Ethiopia into a landlocked country. War and conflict with Eritrea lasted for years, and eventually, in 2018, Ethiopia was forced to accept the new borders. However, independent Eritrea, under a one-party authoritarian system, made little progress and today is one of the most underdeveloped countries. A significant portion of its young workforce has emigrated. Ethiopia, which is organized along ethnic lines, has also experienced other border conflicts, and scattered civil wars continue. Despite all its problems and hardships, Ethiopia is less chaotic than the other two countries. It has also, through a formal agreement with Somaliland, gained access to its coastline – an issue to which Somalia has strongly objected. Given the risk of renewed conflict between Somalia and Ethiopia, this could further compound regional problems.

Yemen was unified in 1990 through the merger of the North and the South. After the collapse of the Soviet-backed government in South Yemen, US financial aid to Yemen was established. However, when Yemen refused to join the US-led coalition following Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, the aid was cut. In 1994, conflict between the North and South resumed after the vice president was expelled and the South declared secession. At the same time, al-Qaeda was expanding its influence in Yemen, and the country gradually became one of al-Qaeda’s key bases. In 2000, al-Qaeda attacked a US ship off the coast of Yemen, killing several sailors. This led to renewed rapprochement between the United States and Yemen, along with financial and military assistance. Shortly thereafter, al-Qaeda attacked the US embassy in Sana’a, killing many diplomats and staff.

The uprising of Yemen’s Zaydi Shiites led by Hussein al-Houthi – who was eventually killed – resulted in prolonged and bloody conflicts between the Zaydis (thereafter known as the Houthis), along with foreign interventions and Iran’s Islamic regime and Saudi Arabia’s rivalry, fragmenting Yemen. In the south, a separatist faction known as the “Southern Transitional Council” confronted the central government, whose territorial control gradually shrank. The Houthis advanced to the point that they captured Sana’a, the capital, forcing Yemen’s government to relocate to Aden. As a result, Yemen is now effectively divided into three parts: the Houthis in the north with the Iranian regime’s support; the Yemeni government in Aden backed by Saudi Arabia; and the rest of the south under the control of the Southern Transitional Council (STC) supported by the United Arab Emirates. At the time of writing this article, Saudi Arabia bombed the headquarters of the southern separatist leader – who was also a member of Yemen’s Presidential Leadership Council – after inviting him to Riyadh and being refused. Subsequently, he fled to Abu Dhabi and STC announced its dissolution, but breakaway separatists continue their fight.

Regional Actors

Apart from the role of the major powers in the current turmoil in these three countries, competition among regional actors has brought even greater misery to the people of this region. The details of the power struggles among regional powers are themselves another story. However, it is necessary to point out some of the most important new actors in this region: Israel.

Access to the Red Sea has been vital for Israel ever since it occupied the port of Eilat through a deal with Emir Abdullah I, King of Jordan, promising Jordan would control the West Bank. The port of Eilat, adjacent to and effectively attached to Jordan’s port of Aqaba, gains access to the Red Sea through the Gulf of Aqaba (Map 4). Israel has sought to establish relations with some of the countries bordering this sea. It has maintained good relations with Ethiopia and openly supported Ethiopia during Eritrea’s independence movement, fearing that Eritrea – with its predominantly Muslim population and more than a thousand kilometres of Red Sea coastline – could pose a problem for Israel. Nevertheless, after Eritrea’s independence, Israel attempted to establish relations with it. Following medical treatment of Eritrea’s president in Israel, arranged by the US ambassador, official relations between the two countries were established in 2022. However, due to disagreements whose reasons were not disclosed, Eritrea did not accept Israel’s ambassador, and both embassies are currently without ambassadors.

In recent years, Houthi missile and drone attacks, as well as their attacks on Israeli and other ships, have drawn Israel’s attention toward establishing and expanding relations with Somalia and (southern) Yemen. For this reason, Israel has been the only country to recognize Somaliland, which has seceded from Somalia, and just a few days ago, Israel’s foreign minister visited Somaliland. Israel’s main objective – ostensibly the promise of technical assistance to Somaliland’s agriculture – is clearly to enter this sensitive and strategic region to counter the Houthis and Israel’s other adversaries.

At the time of writing this article, rumours circulated that Israel’s intention in recognizing Somaliland was the forcible displacement of Palestinians from Gaza to Somaliland. Later, Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohammad, in an interview with Al Jazeera, confirmed this. He said that “Israel wants to force Palestinians out of their country and force Somalia to bring another nation into its territory.” He also added that Israel is trying to open a military base there, emphasizing that this will have dangerous consequences for the region and, given the strategic significance of the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea, will have a global impact.

In addition, beyond its repeated bombings of Yemen in areas controlled by the Houthis, Israel favours strengthening the southern separatists, namely the Southern Transitional Council. The extent to which the United Arab Emirates’ support for this separatist movement is connected to Israel is unclear. However, given the increasingly close formal relations between the UAE and Israel, and the UAE’s role as one of the main supporters of Trump’s “Abraham Accords,” it can be assumed that Israel has greater expectations from this relationship. The southern separatists currently control the strategic island of Socotra in the Arabian Sea, located near the tip of the Horn of Africa off the coast of Somalia. Israeli influence in this area could help advance its expansionist policies. That said, Saudi Arabia’s recent attack on areas controlled by southern Yemeni separatists – accompanied by the humiliation and retreat of the UAE, and the dissolution of STC – could create obstacles to such plans.

Two major and wealthy powers on the Arabian Peninsula – Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – are other key actors in the region. Each, in competition with the other, seeks to expand its influence by exploiting failed states not only in its immediate neighbourhood but also in Africa. Notably, Saudi Arabia tends to support still-existing central governments, while the UAE supports separatist movements within those states. Clear examples include Yemen, Somalia, Sudan, and Libya. Other important regional actors include the Islamic Republic of Iran, with its close relationship and support for the Houthis, and the government of Turkiye, which harbours ambitions of reviving the Ottoman era and expanding its influence in the region.

In short, despite all the internal problems and obstacles stemming from underdevelopment in various fields, the three countries of Somalia, Yemen, and Ethiopia had significant potential for development. However, the policies of the major colonial and imperial powers, their rivalries, the Cold War, and current regional interventions not only failed to remove these countries’ internal barriers to development but instead intensified them. What we are witnessing is the deepening of social, economic, and political backwardness, tribalism, religious fundamentalism, and endless internal wars that have torn the fabric of Somalia, Yemen, and, to a lesser extent, Ethiopia. •

The Farsi version of this article appeared in Zamaneh.