The Many Faces of (In)Equality

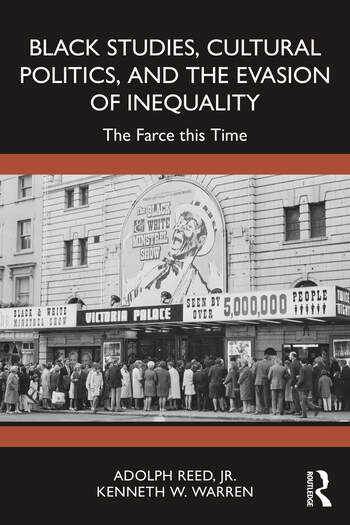

Adolph Reed Jr. and Ken Warren, two of the most prominent participants in the race-vs-class saga haunting the left, return here to deepen their case and do so with great clarity. Along the way they provide an exemplary illustration of how to seriously think – analytically, historically, and politically – about transformative social change. This makes their new book, Black Studies, Cultural Politics, and the Evasion of Inequality, (Routledge, 2026), a must-read whether the reader is looking to find the holes in Reed and Warren’s reasoning, confirm his/her sympathy with the authors, or is as yet undecided.

At the heart of Reed and Warren’s arguments lie contradictions in claims made within black politics about equality. Such claims have centered primarily on the racially based income and wealth disparities between whites and blacks. This gap is real, and it is obviously legitimate to raise it. But as Walter Benn Michaels has repeatedly noted, prioritizing catching up to poor and working-class whites, especially after the last four decades of assaults on all workers, sets the bar disappointingly low.

Such a focus also – especially – obscures the markedly larger and accelerating overall inequality in the US. The top 10% of households account for as much consumption as the rest of the population. They also own double the wealth of the other 90%. Furthermore, limiting the focus to the black-white difference diverts attention, often disingenuously, from the rising inequalities among blacks (The Gini Coefficient, a measure of group inequality, is today higher among blacks than among whites).

The Shifting Tides of History

The charge that virtually nothing has changed for American blacks or in the nature of white American racism reflects a remarkably static view of history. History is not just ‘the past’; it shifts and bends. To ignore its changes is disingenuous on three critical counts. First, the notion that nothing has changed is simply not true; getting formal status as a human being and ending Jim Crow matter and, whatever the limits, this has translated into significant material gains for black families. Second, the form of oppression matters; there are great differences between the oppressions of slavery applied to one group and the oppressions of American capitalism applied across working families whatever their color.

Third, a crucial dimension of the advances that blacks have made since the passing of the civil rights acts of the mid-sixties is the rise of a black elite of professionals, politicians, and investors who have come to play a predominant role as self-selected leaders of the black population and the subsequent mediators between blacks and the wider society. Their underscoring of specifically black oppression and victimization has, however, studiously avoided the concrete daily concerns of black workers that overlap with their white counterparts, such as jobs, housing, education, and healthcare. The consolidation of this elite’s role, Reed and Warren emphatically argue, constitutes their emergence as a class with interests distinct from black needs.

The expression of these dynamics in academe, the authors further emphasize, has been a turn away from the political economy of capitalism to a ‘cultural turn’ that romanticizes black history. Even when the rich literature of black oppression and its ‘legacies and scars’ has conveyed genuine anti-capitalism, Reed and Warren note that what results is an Afro-pessimism with nowhere to go. Absent the identification of an agency potentially up to challenging capitalism, fatalism rules. Black politics tends to be reduced to mobilizing white guilt and dependence on clientelist politics, not to transforming the conditions of its alleged constituency.

The vision that Reed and Warren unashamedly uphold is a commitment to “a world in which justice is imagined and realized from the standpoint of those whose labour creates what is truly human and truly valuable.” Placing working people at the core of their perspective is neither arbitrary, a matter of class reductionism, an insensitivity to other oppressions or identities, nor an essentialist understanding of workers as spontaneously radical. It is rather a choice made out of an historically grounded belief not in the inevitability of, but in the potentials of, ‘ordinary’ workers escaping their circumstances and building an alternative society.

Aggravation of America’s Inequalities

None of this is to deny the past failings of unions to address racial (and other) inequalities. The point is rather to recognize that these failings were contingent, not inexorable. As with other obstacles, the challenge is to overcome the failings. The commitment of the authors to a working-class politics comes with the recognition that class politics – as opposed to the particularism of defending group interests (whether of unions or other communities) – lies in the qualitative equality of all members of the class, independent of color or other differences. This is not a matter of dismissing differences but of creating the wider solidarities needed to effect change, and not a matter of only rhetorical support but of actively struggling for that equality within working-class organizations and the larger society.

Trump’s skewing of electoral districts to undermine the weight of black voters and his fascist-like attacks on immigrants certainly reflect and nurture racism. But they are more than that; they are part of a larger attack on America’s already constrained democracy and a sordid aggravation of America’s already obscene social inequalities. These are battles that, Reed and Warren repeatedly insist, blacks standing alone cannot win. Without the creation and development of a broader alliance across black, white, and workers of whatever color, ghettoized struggles are condemned to rhetorical radicalism and sporadic protests.

In their earlier works, Reed and Warren have reminded us of the distorted or forgotten spirit of Phillip Randolph’s speech at the 1963 March on Washington. Randolph was the head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a black union and a central organizer of the March, and the opening speaker that day. Addressing the denial of black civil rights, he attacked private-property rights standing above human rights and noted that, because of the particular suffering of blacks, “[I]t falls to us to demand new forms of social planning, to create full employment, and to put automation at the service of human needs, not at the service of profits… Negroes are in the forefront of today’s movement for social and racial justice, because we know we cannot expect the realization of our aspirations through the same old anti-democratic social institutions and philosophies that have all along frustrated our aspirations.”

This spirit of recognizing the larger battle, and of blacks even leading in the building of working-class unity that incorporates but also transcends unflinching opposition to racism and discrimination, is something that the book and the life work of Reed and Warren have powerfully contributed to. •