Sudan: How Imperialism Fuels War and Mass Violence

The civil war today tearing apart Sudan is not just a conflict between rival generals. Rather, it is the direct and tragic consequence of the plundering of the resources under the country’s soil for the benefit of foreign powers. Only an end to outside interference and the mobilisation of the Sudanese people to force the creation of a civilian government without military involvement can put an end to the horror.

According to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), this conflict has already displaced 13 million people: 8.6 million internally displaced persons and more than 4 million who have become refugees abroad. Nearly 150,000 people have lost their lives. The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have committed appalling atrocities, particularly in El Fasher, which is now in the hands of paramilitaries following an eighteen-month siege. The fall of this strategic city, which had offered shelter to 260,000 refugees, was accompanied by rampant famine and numerous atrocities. These included summary executions, sexual violence, attacks on fleeing civilians, and executions of unarmed men, as recently confirmed by the UN Human Rights Commission.

A Long History of Exploitation

For decades, the appetites of imperialism have seriously destabilised Sudanese society. The country, of great strategic importance due to its long coast along the Red Sea, its overall size (giving it seven borders with other African countries), and its mineral wealth (uranium and gold mines, Nile resources) has been constantly targeted.

While the period from 1993 to 2020 saw Sudan appear on Washington’s list of state sponsors of terrorism, this classification also served as leverage to put pressure on the Sudanese state in the context of civil war. This ultimately led to the secession of South Sudan in 2010.

The Betrayed Revolution of 2019

In April 2019, a massive popular uprising overthrew dictator Omar al-Bashir. This revolt was led by revolutionary neighbourhood committees and civilian forces, supported by a network of medical doctors and lawyers.

However, Bashir’s regime was supported by a military elite that itself benefited from the plundering of national wealth by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt, with these powers using illegal channels to smuggle gold and other resources from the country.

After Bashir’s downfall, the West supported a transitional government. The Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) agreed to form a new administration in August 2019 with military involvement. The popular movement, despite its strength, found itself marginalised: real power remained in the hands of the army, which controlled the economy and public finances. The Sudanese Communist Party was a founding member of the FFC but refused to participate in the government as long as the military was involved.

In 2020, Donald Trump made Sudan’s removal from the list of state sponsors of terrorism conditional on General Burhan paying $335-million to victims of terrorism, thereby guaranteeing US and Israeli support for the military leadership.

The transition was definitively sabotaged in October 2021, when the military concentrated all power in a coup orchestrated by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the army, ousting civilian Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok. This coup “tore up the Transitional Constitutional Charter, plunging the nation into a prolonged and catastrophic war.”

Proxy War

In April 2023, war broke out between two armies: the regular army led by Burhan, who is president of the transitional council, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) commanded by Mohamed Hamdan Daglo (Hemedti), who is vice-president of the same transitional council. Both armies are products of Bashir’s dictatorship: the RSF are the former Janjaweed – the militias that wreaked havoc in Darfur – who Bashir and Burhan transformed into a paramilitary force in 2013.

Today, the war is no longer a simple local affair but a proxy war between different foreign powers. All of them covet Sudan’s riches. The country has become the battleground for two petro-monarchies, with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) supporting the RSF and Saudi Arabia allied with the regular army. Sudan’s gold industry is the driving force behind this conflict, with almost all trade passing through the UAE before it enriches the belligerents.

The “Quad” (the United States, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates) has started negotiations for an agreement. But “any agreement negotiated under these conditions will only reproduce the crisis, as history has repeatedly shown in Sudan and elsewhere,” the Sudanese Communist Party insists. Current attempts to reach an agreement threaten to divide the country once again between the army and the RSF.

Escalating Foreign Interference

The United States and Israel are seeking to control the north of the country by way of the army leadership. For Israel, this region is even considered as a possible location for the forced resettlement of Palestinians. The Sudanese Communist Party warns against this logic, deeming this “part of the ‘Greater Middle East’ project, whose strategic logic aims to dismantle national units in the region in order to facilitate imperial expropriation.” This has taken the form of “the systematic liquidation of the Palestinian cause, the genocide and forced displacement of the Palestinian people, [and] the attempt to erase the Sudanese revolution.”

The United Nations’ Secretary-General António Guterres has called for an end to foreign military support, stressing that “the problem lies not only in the fighting … but also in growing external interference.”

European Weapons

Amnesty International has revealed that the warring parties are receiving French-made weapons mounted on UAE armoured vehicles used by the RSF, which is a “clear violation of the UN arms embargo” on Darfur.

Amnesty International Secretary General Agnès Callamard is categorical, in this regard: “All countries must immediately stop supplying any weapons and ammunition, whether directly or indirectly, to the parties to the conflict in Sudan,” and they “must respect and enforce the arms embargo on Darfur … so that more civilians do not lose their lives.” British-made weapons have also been supplied by the United Arab Emirates to the RSF despite rules that require a halt to exports if there is a clear risk of weapons being rerouted toward embargoed areas or being used to commit atrocities.

Mobilising the Population

Faced with this orchestrated dismemberment of the country, the Sudanese civil resistance is calling for popular mobilisation to stop the war.

For the Sudanese Communist Party, “what is needed now is to build the broadest possible popular national front, uncompromising in its demand for an immediate cessation of hostilities, a revival of the revolutionary dynamic, and the preservation of Sudan’s unity.” The overthrow of the two illegitimate regimes is imperative, and it requires the complete withdrawal of the military establishment, the RSF, and all militias.

There must be an end to foreign interference, and an end to any support for an agreement that maintains the military’s grip on the country. Both armies must return to their barracks, and the war crimes committed by both sides must be brought before the justice system. The popular movement rightly demands that the unity and sovereignty of the country must be preserved and that power must be returned, in full, to a civilian government.

The stakes extend far beyond Sudan’s borders alone: as the Sudanese Communist Party points out, the logic of imperialist dismemberment of the country threatens “not only peace but the sovereignty of Sudan and the future of the African continent.” •

This article first published in English on the transform! Europe website.

The Structural Roots of Sudan’s Ongoing Devastation

The ongoing war in Sudan has resulted in the world’s largest displacement crisis, with more than 14 million people forced out of their homes and seeking refuge both in and outside of the country. This figure is often cited to highlight the devastation caused by the current civil war, but the conflict is by no means Sudan’s first encounter with war and destruction.

In fact, the country has long been known for its persistent and numerous wars, including Africa’s longest-running civil war in South Sudan prior to the latter’s independence, the Darfur War in the early 2000s, and the South Kordofan and Blue Nile War from 2011 to 2020. The current war, now stretching into its third year, has proven more devastating than any of its predecessors. The reasons for this devastation lie in structural factors shaping the country’s economy and demography, as well as the accumulated harms caused by decades of intermittent war.

Core and Periphery

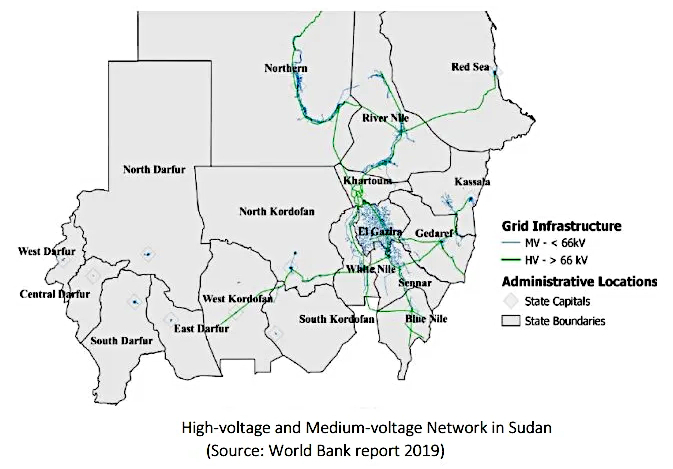

Prior to 15 April 2023, the day fighting erupted between the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), the people of Sudan were already struggling with the consequences of extreme underdevelopment, compounded by the extreme centralisation of infrastructure and resources. Access to electricity, for instance, was limited to just 30 – 50 percent of the population, with frequent interruptions even for those connected to the grid. Moreover, this access was highly uneven geographically: the majority of electrical infrastructure was concentrated in Khartoum and the neighbouring state Gezira, with only precarious connections reaching a few urban centres in peripheral states.

This setup is not unique to the electrical grid alone but extends across all public service infrastructures, from health and education to telecom and banking. The same pattern can be observed in the distribution of productive economic activities, with over 70 percent of Sudan’s large-scale industrial facilities concentrated in the capital, Khartoum, and Gezira.

This reality has a dual impact, fuelling conflicts while simultaneously enabling successive Sudanese governments to maintain control over the country despite persistent wars in the periphery. The extreme underdevelopment in peripheral regions has logically bred grievances among local populations that, when combined with the central state’s violent suppression of dissent, creates fertile ground for the rise of armed groups.

Another critical factor was the strategy employed by successive governments: arming segments of the peripheral populations and forming paramilitary militias. These groups were used to crush dissent or forcibly displace communities from resource-rich areas – a strategy that proved effective, as the peripheries’ underdevelopment supplied a steady pool of desperate youth who saw joining militias as their only path to survival. At the same time, it granted the government a low-cost suppression tool, minimising the state’s direct involvement.

One of the militias created through this strategy was the RSF, now one of the two main warring parties in the current conflict. The RSF seized control of the capital in April 2023 and expanded its control to Gezira by December of that year – the first time in Sudanese history that warfare reached the nation’s economic heartland. The consequences extended far beyond the immediate geography of military operations. Millions were displaced from the capital, which had previously housed over a quarter of Sudan’s population. These displaced populations sought refuge in other states that lacked even basic infrastructure for their native inhabitants, let alone capacity to accommodate newcomers.

The destruction of the industrial base in Khartoum and agricultural projects in Gezira led to catastrophic economic losses, with estimated sectoral GDP reductions of 70 percent in industry, 49 percent in services, and 21 percent in agriculture within the first year. These economic shocks translated directly into plummeting quality of life, vanishing incomes, and disappearing job opportunities nationwide. The current devastation thus stems from a dual legacy: both the immediate violent atrocities of the ongoing war and the accumulated developmental injustices of previous decades.

Old Patterns with a New Twist

Despite this reality, descriptions of the current war often emphasise its “unprecedented” violence and crimes against humanity, a framing that erases the suffering of millions who already endured decades of war and underdevelopment. The atrocities committed by the RSF, SAF, and allied militias on both sides merely continue long-established patterns of violence.

RSF-controlled areas are witness to their characteristic brand of chaos: fragmented governance through decentralised gangs with loose ties to a central leadership, widespread random violence, rapes, and systematic looting as both recruitment tool and reward for fighters. These are not new tactics – the same strategies were employed by the RSF in Darfur and other parts of Sudan for 20 years. The only difference now is that they are no longer taking place under the orders of the central government but indeed against them.

In SAF-controlled zones, the violence follows a more bureaucratic pattern: forced evictions of low-income communities under the pretext of “safety” and without providing alternatives, mass arrests of street vendors and underprivileged communities accused of collaborating with the enemy, and extrajudicial killings carried out by proxy militias deliberately distanced from the state – a tactic perfected with the RSF itself in earlier years.

Both factions prioritise attacking each other’s territory while neglecting civilian needs in their own. Their sole focus remains securing military assets, as seen when the SAF repeatedly abandons populations to RSF brutality in favour of protecting weapons and personnel. Al-Fashir in North Darfur exemplifies this: besieged by the RSF for over 18 months, the SAF remains barricaded in its fortified central base while outsourcing combat to the so-called “Joint Forces,” a new militia cobbled together from signatories to the Juba Agreement, a deal signed in 2020 between the transitional government and several armed groups, advertised as a path to ending long-standing conflicts, particularly in Darfur and other regions.

This systemic disregard for human life reflects deeper historical pathologies. In fact, the placement of military headquarters in every urban core reveals a colonial-era logic: state infrastructure takes absolute precedence over civilian survival. Given that the Sudanese army itself, as well as several major governance entities and tools, did not undergo any review or reform since its creation by the British colonizers, such a result is only logical. This dynamic, whereby the state treats its people as colonial subjects rather than citizens, is by no means new but indeed foundational, dating back to Sudan’s inception as a state never fully decoupled from its oppressive origins.

Caught in the Crossfire

Sudan’s popular resistance, which first showed its face in the 2019 revolutionary uprising, sought to oppose the erasure of past injustices while exposing ongoing ones. Yet the current war has subjected the movement, which demonstrated remarkable resilience in recent years, to a very severe test – partly as a consequence of the aforementioned centralisation.

When protests first erupted against deposed President Omar al-Bashir in late 2019, they represented a quantitative transformation away from the previous civil disobedience under his 30-year rule. These included isolated protests against water shortages, underdevelopment, forced displacement, the detention and murder of activists, and other state-led crimes, as well as scattered labour struggles like the 2016 strike in opposition to rising medication prices. The December 2018 uprising spread simultaneously across dozens of cities and villages nationwide, facilitated by the emergence of neighbourhood resistance committees designed to coordinate protests while minimising state repression’s impact.

These committees became the vanguard of resistance against both al-Bashir and the subsequent transitional government as it increasingly betrayed the revolution’s goals. Representing a qualitatively new political force, they broke the monopoly held by traditional parties in a political arena closed to new actors for decades. Their members, drawn from a young demographic with bleak economic prospects, were rooted in local communities, more attuned to local realities and less prone to compromise. This manifested in their steadfast opposition to economic liberalsation and the normalisation of military rule, in sharp contrast to the established parties that joined the August 2019 power-sharing deal with the military.

Following the October 2021 military coup, the committees spearheaded a revitalised resistance movement, now unshackled from transitional government propaganda. At their peak, over 8,000 committees nationwide coordinated protests and developed comprehensive political charters advocating complete military withdrawal from governance. Through sustained demonstrations, they successfully immobilised the coup regime for more than a year.

The establishment’s response to this grassroots movement followed predictable patterns: either outright dismissal or co-optation. Traditional reformist parties sought to hijack protests, claiming they supported restoring the pre-coup partnership government – a manoeuvre that backfired as protesters publicly expelled their representatives from protests. Similarly, international actors like the UN Mission in Sudan pushed for renewed military-civilian partnerships despite popular opposition, even attempting (unsuccessfully) to draw resistance committees into these negotiations. This persistent pattern of rewarding military factions with political legitimacy directly enabled their continued violence, including the current war.

While retaining revolutionary demands for civilian rule and the core slogan of “freedom, peace, and justice,” the committees could not fully escape Sudan’s structural centralisation. Although they introduced new voices to political discourse, they remained constrained by elitist frameworks, as the following examples and manifestations expose. Their nominally horizontal structures, both internally and in inter-committee coordination, proved inadequate to overcome centralised power dynamics.

Several manifestations of these limitations emerged:

- The charter drafting process, while theoretically inclusive (with state-level deliberations preceding a national synthesis), saw Khartoum’s document disproportionately dominate discourse, often being mistaken for the national consensus – a direct consequence of infrastructural centralisation in education and communications that gave Khartoum committees a louder voice than others.

- Internal committee dynamics reproduced patriarchal norms, valorising militant protest roles over organisational work, leading to declining female participation compared to the revolution’s early days.

- Despite some electoral practices, most committees failed to develop truly inclusive decision-making structures, remaining dominated by politically active young men rather than becoming genuine neighbourhood assemblies.

- Their political proposals focused on capturing existing state institutions through electoral strategies rather than capitalising on the situation of dual power to build alternative community-controlled systems for resource management.

The Sudanese experience confirms a century of Marxist theoretical observations: while the oppressed naturally recognise injustice and possess tremendous revolutionary energy, transforming this potential into lasting change requires both scientific organisational methods and direct popular control over resources, tasks historically fulfilled by revolutionary Marxist parties.

When war erupted in April 2023, most resistance committees initially rejected the conflict and refused to support either warring party – both being military factions the movement had opposed for years. The resistance collectively mobilised through what were called “Emergency Rooms,” new community organisations formed to provide essential services to war-besieged and displaced populations as state institutions abandoned their responsibilities. To this day, these “Rooms” remain the primary support system for those most affected by the war.

Yet the Sudanese movement’s chronic lack of a comprehensive revolutionary political programme manifested again in critical ways. The Emergency Rooms largely framed their work as temporary volunteer charity rather than recognising their potential to establish genuine bottom-up systems of service provision and community organisation – a missed opportunity for transformative praxis.

No Liberation without Organisation

The resistance committees themselves, despite their principled anti-war stance, gradually shifted toward an untenable middle position: opposing the war while paradoxically supporting what they conceptualised as “the Sudanese state” – an entity they portrayed as transcending its military apparatus, existing as a benevolent, apolitical institution. This fundamental misunderstanding of the state as a neutral body rather than as the ruling class’s instrument particularly influenced urban committee members, some of whom ultimately embraced overt SAF support under the justification of wartime exigency.

Proponents of this approach – within both the committees as well as pro-revolutionary intellectual circles – rationalise their position by invoking what they characterise as an unprecedented existential threat to Sudan’s state and people. While historically inaccurate given Sudan’s long history of conflicts, this perspective becomes comprehensible when considering the effects of centralised development discussed earlier. The predominance of urban voices within the resistance movement – largely from areas previously insulated from Sudan’s peripheral wars – has meant that personal wartime experiences now distort political analysis, eclipsing the longstanding grievances of marginalised regions that predate the current conflict.

In examining both the war’s devastation in Sudan and the resistance movement’s limitations, two stark realities emerge: the catastrophic consequences of centralised power and development, and the impossibility of fundamentally challenging these structures without a coherent revolutionary theory and a disciplined party committed to its implementation. By reaching Sudan’s urban political and economic core, the current war has not only spread destruction nationwide, but also exposed the critical weakness of a resistance movement that – despite remarkable resilience – lacked what it needed most: a revolutionary organisation dedicated to transforming foundational power structures rather than merely resisting their symptoms or negotiating superficial leadership changes.

The path forward becomes clear through this painful lesson: lasting liberation requires moving beyond spontaneous resistance to build organised revolutionary capacity. Only with an objective analysis of state and economic power, as well as the impacts of the colonial legacy – combined with disciplined organisation that unites urban and rural struggles – can Sudan break its cycle of violence and underdevelopment. The alternative is the perpetual recurrence of today’s tragedies under different guises, as the root causes remain unaddressed and the structures of oppression persist. •

This article first published on the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung website.