Dissent, Reason, or Reasoned Dissent: Trumpism Amidst Mamdani

Across the world, neoliberalism has exhausted the moral and material foundations of the liberal order that once began as a promise of equality, justice, prosperity, efficiency, and freedom. In practice, it has produced deep inequality, widespread dispossession, ecological devastation, and the disintegration of collective life. However, neoliberalism’s most enduring damage lies not only in its economic consequences but also in its epistemic effects. It has weakened the categories through which societies understand justice, equality, community, and reason. The rationality that once carried an emancipatory promise has been confined to instrumentality, and dissent, once regarded as the moral voice of reason, has increasingly taken the form of resentment, evident in populist backlashes that convert structural grievances into affective antagonism.

This article examines how neoliberalism’s crisis generates two distinct forms of dissent. One finds expression in reactionary populism. It emerges as hatred and ultra-nationalist politics embodied in the figure of Donald Trump. The other emerges as the reconstitution of dissent as a collective, rational, and emancipatory practice, visible in the politics of Zohran Mamdani and the socialist movements that have grown around him. The contrast between Trumpism and Mamdani illustrates the divergent trajectories of dissent in a world shaped by neoliberal globalization.

We argue that to recover dissent as a meaningful political act, it is necessary to revisit its relationship with reason. Historically, dissent has not been the opposite of reason but its highest expression. From Socrates to Marx, from Rosa Luxemburg to B. R. Ambedkar, dissent has rested on the conviction that reason must be exercised collectively against domination. However, under neoliberalism, dissent has been captured by ultra-nationalist forces, and reason has been subordinated to neoliberal ideology of market. The task for left is to restore the connection between them so that dissent can once again serve as a political practice capable of challenging dominant ideology, and reason can recover its role as a collective and emancipatory capacity.

Dissent, Reason, and the Political Act

The analysis is structured in three parts. The first situates dissent as a political act grounded in Marxian and critical-theoretical traditions and contrasts it with liberal accounts that ultimately pave the way for reactionary right-wing populism. The second evaluates Trumpism as the degeneration of dissent into unreason. It interprets Trump’s politics as a distorted response to neoliberal dislocation and imperial decline. The third examines Zohran Mamdani’s politics as an instance of reasoned dissent, where critique is reconnected to collective agency. The conclusion argues that the future of democratic socialism depends on reclaiming the unity of dissent and reason against the combined pressures of neoliberal damage and right-wing populism.

Dissent is more than just disagreement. It is a political act of negation. A refusal to accept what is presented as natural, necessary, or inevitable. The dissenter does not simply differ in opinion. They interrupt the reproduction of domination. This interruption may take the form of a speech, a strike, a boycott, or a mass movement. However, dissent can be captured, domesticated, commodified, or even mobilized by the very powers it seeks to oppose. There are two paradigms that engage with dissent as a driving force of change: Liberalism and Marxism.

In liberal tradition, from Locke to Mill, dissent is upheld as an individual right, the cornerstone of freedom of speech and conscience. But this conception remains narrowly individualistic and ultimately depoliticized. As Herbert Marcuse argued in Repressive Tolerance (1965), liberal democracies neutralize dissent by transforming it into safe pluralism by creating a space for a diversity of opinions. However, at the same time, it leaves existing social relations untouched. Put differently, liberal dissent operates within the existing ideology. Marx had already anticipated this critique when he observed that bourgeois liberty universalized a form of freedom suited to private property: the freedom to speak, trade, and own, but not to transform the material conditions of life.

In contrast, in the Marxist tradition, from Karl Marx to Antonio Gramsci, dissent ceases to be a matter of private conscience only and becomes collective praxis. It arises from the structural antagonisms of capitalist society, such as between labour and capital, accumulation and subsistence. When workers strike, peasants resist dispossession, or students challenge the privatization of education, dissent transcends protest and becomes a social force. It no longer operates merely within ideology but as an attempt to transform ideology itself. In Gramsci’s terms, such acts signify the formation of counter-hegemony that contests the ruling ideas of the dominant classes.

Mainstream political theory, rooted in liberal rationalism, often treats dissent and reason as opposites: the emotional versus the rational, rebellion versus deliberation. However, within critical traditions, dissent represents not the negation of reason but its recovery. In this tradition, it was believed that reason has the potential to liberate humanity from superstition and tyranny. However, as Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno demonstrated in Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944), reason under capitalism became instrumentalized: a means of calculation, efficiency, and domination. What appeared as rationality in the market, the bureaucracy, or the modern state was, in fact, a form of unreason, as it helps to subordinate human ends to the imperatives of profit and power.

Critical reason, by contrast, preserves the emancipatory promise while turning its critique upon the social structures that deform it. As Horkheimer argued in Eclipse of Reason (1947), critical reason evaluates social arrangements not by their technical success but by their capacity to advance human freedom. Marx’s critique of political economy is the fullest expression of this orientation. His inquiry into the categories of value, freedom, and equality revealed that these were not timeless abstractions but historically specific expressions of capitalist relations. In exposing their contingency, Marx transformed reason into a revolutionary force. The task of critical thought, therefore, is not to abandon reason as a bourgeois construct but to reclaim it as a weapon of emancipation, to defend it against its technocratic domestication by ruling classes and restore its connection to collective human liberation.

In the neoliberal era, both dissent and reason have been profoundly degraded. Decades of globalization, financialization, and privatization have depoliticized everyday life, replacing collective struggle with individualized anxiety. The rhetoric of choice, empowerment, and personal fulfilment has displaced the language of class. Under such conditions, dissent risks becoming spectacle, and reason risks degenerating into strategy, emptying both of their transformative political content. We inhabit a world that protests incessantly, yet rarely challenges the structural roots of crisis.

Therefore, the task of contemporary emancipatory politics is to recover dissent as the collective exercise of reason and reason as the critical ground of dissent. Only when critique is rejoined with struggle and reason reclaimed from its instrumental form, can politics regain its transformative horizon. In this sense, the renewal of democratic socialism depends upon the reactivation of reasoned dissent as the basis of collective emancipation.

The Unreason of Dissent: Donald Trump

The case of Donald Trump presents how dissent, under neoliberal conditions, devolves into spectacle rather than structural opposition. In this instance, dissent does not disappear. It is reorganized in a way that strips it of its emancipatory potential and rearticulates it as ultra-nationalist and imperial resentment.

It is crucial to recognize that Trumpism did not emerge as a rupture with neoliberalism but rather as an expression of its internal contradictions. Prabhat Patnaik, in Neoliberalism and Fascism (2020), argues that the rise of ultra-nationalist tendencies in advanced capitalism arises not from the overthrow of neoliberalism but from its crisis of reproduction. Over four decades, neoliberal restructuring eroded the material basis of working-class life in the United States while concentrating unprecedented wealth in finance, digital monopolies, and globally dispersed production networks. Industrial decline, wage stagnation, and the dismantling of collective institutions such as unions, welfare systems, and public protections created a landscape marked by profound economic dislocation. This domestic crisis was intensified by the gradual decline of the United States’ imperial capacity to discipline emerging powers. Within this context, Trump’s political aggression reflects a pattern noted by Giovanni Arrighi in Adam Smith in Beijing (2007), in moments of hegemonic decline. When imperial power can no longer extract rents and surpluses from the periphery at its previous scale, it often attempts restoration through coercion, myth-making, and spectacular displays of authority. Trumpism represents this inward turn of imperial decline: an effort to reclaim lost primacy through force, exclusion, and ultra-nationalist politics.

Trump’s America First rhetoric converted imperial anxiety into a language of grievance. Yet in Trump’s conception of dissent, the adversary is not capital but its externalized others, including foreigners, migrants, feminists, and cosmopolitans. The global crisis of capital accumulation was reframed as a conspiracy against the greatness of the American nation. Nancy Fraser notes in The End of Progressive Neoliberalism (2017) that such reactionary populism fuses economic grievance with authoritarian protectionism. It forms an alliance between elite fractions of capital and a disoriented working class under the ideological banner of cultural nationalism. This fusion demonstrates how dissent becomes unreasoned under late capitalism. Protest remains widespread, even habitual, yet its critical direction is reversed. When dissent is severed from critical reflection, instrumental reason devolves into a rationality of domination. Its political expression becomes visible in the discourses and practices associated with Trumpism.

At the same time, unreasoned dissent cannot be dismissed as simple irrationality. Its persistence underscores a central contradiction within global capitalism. This contradiction is the widening gulf between the promises of prosperity and the lived reality of dispossession. In the absence of collective institutions capable of converting experience into critique, dissent becomes affective, mythic, and authoritarian. The unreason at work here does not stem from the absence of logic. It stems from the inversion of logic, where rational calculation is mobilized to advance irrational political ends.

In this sense, Trump’s rise highlights not the failure of dissent but the failure of the conditions necessary for reasoned dissent to flourish. The task for the left is not to ridicule the irrationality of Trumpism. Rather, it is to address the longings that fuel it. These longings include the desire for agency, security, and protection against the volatility of market forces. The alternative to Trumpism must be grounded in forms of political agency that reconnect critique with collective organization and transform economic suffering into political consciousness. The task is therefore not merely to oppose Trumpism. It is to render it unnecessary by constructing solidaristic and democratic forms of politics anchored in reasoned dissent.

Politics of Reasoned Dissent: Zohran Mamdani

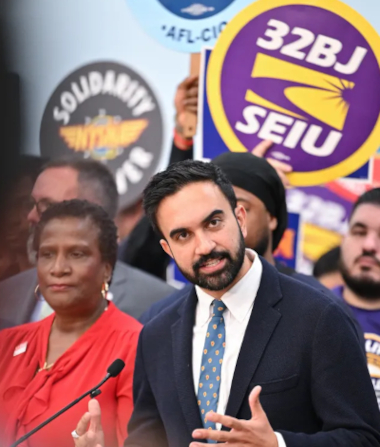

If Trumpism embodies the unreason of dissent, Zohran Mamdani represents its dialectical opposite: the reconstitution of dissent as a conscious, collective, and rational act. His electoral campaign was built not on elite endorsements or corporate money but rather on small-dollar grassroots contributions and volunteer-driven organizing that prioritized political education over media spectacle. In this, the movements that arose in opposition to Trump’s aggressive nationalism, culminating symbolically in Mamdani’s electoral victory, demonstrate that not all dissent born of neoliberal decay turns reactionary. Across cities, workplaces, and university campuses, new coalitions have emerged to reclaim reason as a collective instrument of critique and to rebuild solidarity beyond the divisions of race, class, and geography. Rather than staging politics as performance, these movements rooted dissent in tenant unions, labour struggles, and community-based campaigns that link individual grievances to structural demands.

A parallel development is visible globally, where expanding opposition in the Global South to NATO’s militarism and the resurgence of anti-imperialist solidarities from Palestine to Latin America indicate the re-emergence of a moral and political grammar that resists the unreasoned dissent through which US imperialism seeks to reproduce its hegemony.

Within this shifting terrain, Zohran Mamdani symbolizes what may be described as the politics of reasoned dissent. His politics is shaped by the very social conditions that have fuelled right-wing populism: the housing crisis, spiralling student debt, racialized policing, and ecological devastation. Yet Mamdani interprets these crises differently. Trump transforms discontent into xenophobia and moral panic, whereas Mamdani channels disaffection into a structural critique of capitalism. Crucially, his campaign translated discontent into door-to-door organizing, participatory budgeting demands, and policy platforms co-written with grassroots organizations rather than consultants or donor blocs. His dissent is not animated by nostalgia for an imagined past but by an anticipatory vision of democratic renewal. It challenges globalization not as a call for national closure but as a demand to remake political life along egalitarian and participatory lines.

This distinction is fundamental. Reactionary populism personalizes and moralizes structural contradictions while reasoned dissent historicizes and politicizes suffering. Mamdani’s politics begins from lived grievance but moves toward comprehension and analysis. Where Trump weaponizes resentment, Mamdani situates it within the long histories of accumulation, dispossession, and imperial expansion. His advocacy for universal housing, universal child care, and solidarity with international liberation movements thus emerges as more than policy reform. It represents an effort to revive reason as an emancipatory force, a force that Adorno described as the utopian dimension of critical thought.

The reasoned dissent that informs Mamdani’s movement is not committed to moderation or civility but to clarity. It emphasizes the necessity of connecting immediate injustices with their structural origins. It refuses the two dominant and debilitating logics of the contemporary moment. One is neoliberal fatalism, which naturalizes inequality in the language of efficiency and inevitability. The other is populist nihilism, which dismisses institutions and collective action in favour of affective rebellion. Mamdani’s politics counters both tendencies by asserting that human beings can reflect collectively on their material conditions and act upon that understanding. This assertion resonates with Marx’s account of the transformation of a class in itself into a class for itself.

In this framework, politics is not spectacle. It is pedagogy. Mamdani’s work, and the work of the movements surrounding him, from housing-justice campaigns to the expanding wave of labour organizing in Amazon warehouses and Starbucks stores, embodies the understanding that politics educates. Canvassing becomes a tool for consciousness-building, where conversations about rent burdens or debt become entry points to discuss racial capitalism, public goods, and collective ownership. This pedagogical dimension distinguishes socialist mobilization from populist agitation. By linking thought to action and knowledge to organization, reasoned dissent restores reason as a public capacity rather than a private possession.

This recovery of reason as a shared human capacity is radical in an era in which neoliberalism has privatized not only wealth but the conditions of thinking. Mamdani’s politics challenges the enclosure of knowledge by think tanks, technocrats, and corporate media, returning political judgment to ordinary people engaged in struggle. His socialism, grounded in grassroots organizing and transnational solidarities, reasserts the universality of reason against the fragmentation imposed by identity and capital. In this sense, reasoned dissent becomes a counter-movement to neoliberal ideology and to the reactionary populism that neoliberalism enables.

Reasoned dissent demonstrates that dissent need not collapse into despair, and reason need not serve accumulation. When brought together, dissent and reason form the intellectual and moral foundation for an emancipatory politics that treats critique not as mere negation but as an orientation toward transformation. In this light, Mamdani’s politics should not be read as an attempt merely to temper the excesses of capitalism. It should be understood as an effort to renew the very conditions of political reason. It gestures toward a world in which dissent is no longer a symptom of systemic decay but a practice of collective renewal and a conscious effort to understand the world in order to change it.

The Future of Democratic Socialism

The contrast between Trump’s unreasoned dissent and Mamdani’s reasoned dissent reflects the bifurcation of political life in the declining phase of neoliberalism. Where institutions of collective reasoning such as unions, political parties, and public education have withered, dissent collapses into nihilism. Where these institutions are rebuilt or reimagined, dissent regains its rational and emancipatory character. The central question is therefore not whether dissent persists but what kind of reason animates it and toward what ends it is directed.

Neoliberal capitalism has privatized not only material commons but also the intellectual resources that make public reasoning possible. To resist this enclosure, dissent must reclaim what Kant described as the public use of reason, the shared capacity to deliberate on the conditions of social life. The reasoned dissent cultivated within the movements surrounding Mamdani constitutes this reappropriation. It rejects elitism and challenges market-centered social organization. It reinstates the primacy of struggle as a practice grounded in lived experience and oriented toward collective transformation.

The task before the left is not only to amplify dissent but also to educate and orient it. As Adorno emphasized, the utopian function of thought lies in its ability to imagine the world otherwise. Trump’s populism demonstrates the consequences of suffering severed from critique, while Mamdani’s socialism illustrates what becomes possible when critique is linked to solidarity and organization. The triad of dissent, reason, and reasoned dissent thus defines the contemporary moral and political landscape.

Ultimately, what is at stake is not only the future of democratic socialism but the future of reason itself, and whether it will continue to serve the imperatives of domination or become the collective faculty through which humanity understands and transforms the world for shared well-being. •