Climate Destruction – The Irresponsibility of Capitalist Societies

Within a historically short period, capitalist society has generated enormous wealth but also caused profound ecological degradation and threats to survival. Yet the capitalist market economy is incapable of resolving the problems it has created or of securing a liveable environment.

The Problem

“Capitalist production, therefore, develops technology, and the combining together of various processes into a social whole, only by sapping the original sources of all wealth – the soil and the labourer.” Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. I, ch 15.

To understand the connection between economic activity and its impact on the environment, we must situate economic development within a much broader historical horizon than the usual few decades. Only this wider perspective reveals the destructive problems we have brought upon ourselves through the economic dynamics with which we are so familiar.

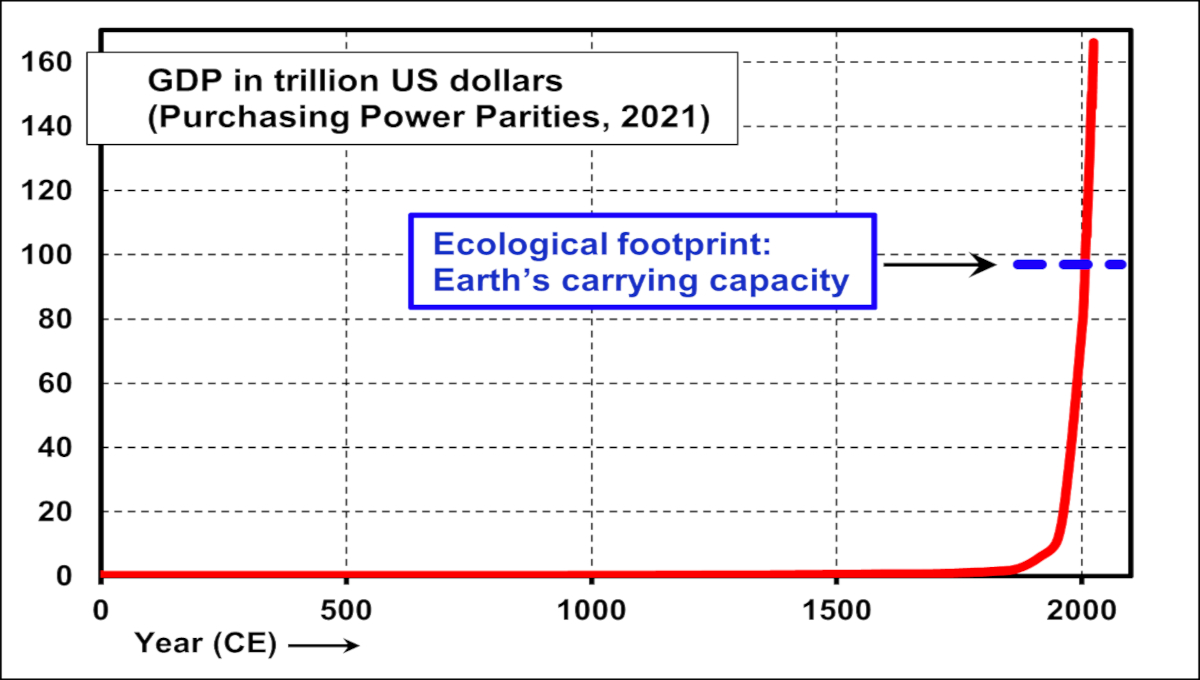

The graph below illustrates the development of gross domestic product (GDP) over the past 2,000 years (based on a long-term analysis by the OECD). It clearly demonstrates the fundamental difference between economic development before and after the emergence of a capitalist market economy around 1800. For thousands of years, the economic wealth of societies remained consistently low. From the year 0 to 1820, global GDP growth averaged just 0.1 per cent per annum.

Global GDP over the past 2,000 years:

The upheavals since then have been profound: “The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together,” wrote Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto in 1848.

The accumulation of GDP wealth since 1820 has two components:

- population growth

- growth in average GDP per capita.

GDP per capita, far more than population, is the real trigger for the GDP explosion in capitalism: in pre-capitalism, population growth accounted for around four-fifths of economic growth. In the market economy of the last 200 years, the opposite is true: even though annual population growth is many times greater than before (12 times higher), it now accounts for only a third of economic growth. Annual productivity growth is now about 100 times higher than it was before the emergence of the capitalist market economy.

Is this explosion in production and transformation sustainable for the environment and nature?

The simplest way to approach this question is by using the well-known indicator of the ecological footprint. It asks: how much nature do we have at our disposal, and how much do we consume for production, transport, waste disposal, and so on? The concept is certainly open to criticism (not every use of raw materials is renewable), but it is simple and widely used.

For the world as a whole, the picture is clear: we are extracting more from the earth than it can continuously regenerate, and burdening it with more pollutants than it can absorb. Only around two-thirds of today’s demand on nature is covered by the planet’s resources; everything beyond that amounts to the overexploitation of the earth’s natural potential.

The key insight, as shown in the graph, highlights two points:

- In earlier centuries, humanity was still in effect infinitely distant from the planet’s ecological limits; the economic transformation of the earth at that time did not approach its absorption capacity.

- With the development of capitalism, an increasing burden on the planet can be seen, rapidly pushing beyond the limits of sustainability.

Given that by 2100 global GDP is expected to be five times its current level, it is evident that what once seemed an almost inconceivably distant limit to the planet’s capacity is now being transgressed at an unstoppable pace. The unrestrained exploitation of nature is intrinsic to the capitalist economic system.

Market Failure

“Climate change is the greatest market failure the world has ever seen.” With this often-quoted sentence, Nicholas Stern, author of the influential 2006 Stern-Review on the costs of climate protection and of anticipated climate change,1 assessed the capacity of a market economy to safeguard a liveable future. One might expect that if the market economy fails so fundamentally and utterly in securing the basis of our existence, the world would urgently seek alternatives to the market. But no: even Nicholas Stern insists that market failure must be countered with more market.

So how can we confront the looming climate destruction? The dominant response in practice is to press ahead with green growth and green capitalism.

Technically, it is perfectly feasible to replace fossil fuels with renewable energy. Yet coal, oil, and gas would have to be substituted not only by solar power but also by other materials: those required for wind turbines, photovoltaic cells, batteries, and so on. Or by materials that help to reduce consumption, such as thermal insulation.

So, the question is: can we solve the climate problem in this way and still sustain economic growth in the long term? Are the earth’s mineral resources sufficient to support long-term economic expansion?

“Our insatiable consumption of resources has tripled over the past 50 years. If we do not change, it could increase by another 60% by 2060. Our current, highly unsustainable consumption and production systems will have catastrophic effects on Earth’s systems.”2

If we continue to extract many raw metal materials at the current rate in a business-as-usual economy, it is clear that even by 2100, which our grandchildren will still be alive to see, the reserves and resources of many materials will be largely depleted. We are therefore facing an even greater and more fateful problem: the earth’s raw material resources are too scarce to guarantee 10 billion people a throwaway mode of consumption in the long term, which is the pursued standard in rich countries.

The standard approach to market-based climate protection is price incentives: for example, making emission-intensive goods more expensive through a carbon tax, thereby limiting their consumption. However, it has repeatedly been shown that such measures have only a very limited effect. The real problem with carbon taxes and similar measures lies in the different price elasticity of the poor and the rich. For poorer households, which (must) spend their entire income on consumption, higher costs due to a carbon tax are a serious burden: they are forced to react and reduce their use of the now more expensive energy. For the wealthy, by contrast, higher consumption expenditures are a minor matter when their savings rate is already 20 or 30 per cent. This means that the reaction of the rich to price changes is far weaker than that of the poor. And since the rich consume many times more than the poor, price incentives often have little impact.

➡ Market-based methods will not get us to our goal. We must decide directly, collectively and democratically on the measures necessary to preserve a liveable environment.

Taking a Closer Look:

polluters and those affected

Is climate destruction man-made, and are we all to blame? Yes and no. Everyone contributes, but the size of individual contributions could hardly be more unequal. A recent Oxfam report states that people in the top 10 per cent of global emitters produce almost 90 times as much CO₂ as those in the bottom 10 per cent.3 It should be noted that the lowest emitters are frugal not out of choice but because they are poor and have no other options. At the other end of the scale, the group of highest emitters largely coincides with the group of the richest.

Sixty per cent of the world’s population does not reach even half of the global average income, while the richest 10 per cent receive five times that average.

Since it is evident that, by its very nature, climate change affects countries in the Global South, thus the poorest countries, far more severely than it does countries in temperate zones, we can conclude that countries and their inhabitants fall, with hardly any overlap, into two groups: polluting countries, which suffer relatively little from the damage they cause, and affected countries, which contribute only marginally to the problem but bear the brunt of its impacts. What applies to countries on average applies even more so to people.

“People living in least developed countries have 10 times more chance of being affected by a climate disaster than those in wealthy countries each year.” (University of Notre Dame, ND-GAIN)

➡ We must address the consumption patterns of wealthy high emitters; this is the key to climate protection.

Solidarity Instead of Capitalist Competition

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”4 This is among the best-known passages in the history of economic thought. Here Smith sums up the human attitude that is indispensable for success in a market economy, and what one can, indeed must, forgo. This is the central creed for market ideologues: concern yourself solely with the maximisation of your business, and everything else – prosperity, balance, stability – will follow of its own accord if the market is left undisturbed.

The ideology of the market economy does everything in its power to generate, cultivate, and reinforce egocentric tendencies in the human psyche, making them as dominant as possible over other feelings. This economic system actively fosters social Darwinism within society.

“Under the conditions of open and competitive markets, which are therefore more effective against excesses in the form of greed, self-interest acquires a moral quality. It drives structural economic change through new ideas and shifting preferences, thereby ensuring prosperity and employment.”5

➡ The market-based capitalist approach, which exacerbates inequality and wealth, and which consistently promotes competitive thinking at the expense of solidarity, is definitely not the right way to overcome the life-threatening problems created by this very same capitalism. •

This article introduces the forthcoming book Climate Destruction – The Irresponsibility of Capitalist Societies (Klimazerstörung – die Verantwortungslosigkeit kapitalistischer Gesellschaften) by Franz Garnreiter.

This article first published on the transform! europe website.

Endnotes

- Nicholas Stern, Stern Review: The Economics of the Climate Change, 2006.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Press Release on the Global Resources Outlook 2024, 1 March 2024.

- Author’s own calculations based on data from Oxfam, Climate Equality: A Planet for the 99% (2023).

- Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), Book I, Chapter II.

- Michael Hüther, “Klarstellung zwei,” German Economic Institute (Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft, IW).