Workers’ Self-Management and the Struggle Against Neoliberalism

The recent book by Marcelo Vieta, Workers’ Self-Management in Argentina: Contesting Neo-liberalism by Occupying Companies, Creating Cooperatives, and Recuperating Autogestion (Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2020), provides a wealth of information and analysis on the emergence of worker-run production cooperatives in Argentina’s crisis-ridden industries. It highlights workers’ prominent role in occupying and self-managing factories that were either shut down or on the brink of closure following the economic crisis of the 1990s. The book also offers fascinating examples of how these worker-managed units were established. Argentina’s labour movement provides valuable lessons for understanding the complexities of workers’ self-management.

To better understand the economic and political conditions that led to these labour movements, it is crucial to briefly consider the historical context of labour organization in Argentina, as discussed in the book and other related sources, particularly its relationship with the state and capitalists. A special focus will be placed on ‘Peronism,’ which significantly shaped labour politics. After that, we will explore some key aspects of the book and conclude with reflections on the concept of workers’ control and its (in-)conceivability under capitalism.

Historical Background

Industrialization in Argentina began in the 1930s under unstable military and civilian governments. The domestic bourgeoisie increasingly sought control over industries under the domination of foreign capitalists, particularly the British. They emphasized import substitution policies, and consumer-oriented industries were growing. At that time, European immigration waves had decreased, and the capitalists’ focus turned to cheap domestic labour from rural areas. The global economic crisis and the decrease in foreign demand for raw materials further accelerated internal industrialization. Simultaneously, the working class was growing, and labour unions with various tendencies – syndicalist, socialist, and communist – emerged, organized under the General Confederation of Workers (CGT).

However, the working class began to emerge as a significant social force starting in 1943, when Colonel and later General Juan Perón, then Minister of Labour in a military government, adopted anti-imperialist and anti-oligarchy rhetoric. He implemented progressive policies in favour of workers and gained the support of the Labour Confederation. Perón had larger ambitions, and the CGT used him to advance its goals. In response to Perón’s growing popularity, the military government removed him from office and imprisoned him. The CGT organized large protests that secured Peron’s quick release and forced the government to hold elections. In 1946, Perón, with broad support from workers and their families, easily won the elections, formed a government, and incorporated some union leaders into the new administration. Although Perón was not a fascist, he was heavily influenced by Mussolini and the fascist model of a centralized, authoritarian state with popular support. He believed that sustained economic development required not only a state-led policy but also a relatively prosperous working class. Accordingly, he adopted a corporatist and class-collaborationist policy, paving the way for cooperation between the CGT, industrialists, the agricultural export sector, and entrepreneurs. He negotiated important collective bargaining agreements and enacted policies such as social security programs, minimum wages, pensions, unemployment benefits, workplace safety regulations, affordable housing for workers, and recreational facilities run by worker-managed cooperatives.

These policies were implemented with the support of the Ministry of Labour and the state bureaucracy. Perón’s powerful wife, Eva Perón, oversaw labour affairs and workers’ relations, securing women’s suffrage. In this class compromise, Perón, while meeting some workers’ welfare demands, convinced capitalists that their interests and the overall growth of capitalism would be secured. He had brought the entire labour movement under his control. This bureaucratic, corporatist, state-centred unionism became known as ‘Verticalismo’.

While workers were pleased with improved conditions, they gradually demanded participation in decision-making at the workshop and factory levels. This was an issue Perón opposed, as his emphasis was on ‘professional unionism’ rather than political unionism. However, during his tenure as labour minister, Perón had frequently promoted the slogan ‘dignity and honour of labour,’ which led workers to demand political transformation in their organizations and greater participation in decision-making. As a result, a form of direct industrial democracy was established, where workers elected shop stewards at each workshop, and the representatives of each workshop formed a ‘delegates’ assembly,’ that elected an ‘internal committee’ (factory committee) to negotiate with management. These important worker institutions played a prominent role during the first two terms of Perón’s presidency (1946–1955), participating in factory management, improving working conditions, addressing complaints, and resisting management pressures. According to various scholars, these institutions acted as political schools for the workers and their organizations.

However, as Vieta notes, this ‘Peronism,’ despite Perón’s remarkable ability to balance and control the demands of employers and workers within a national populist policy, could not avoid ongoing tensions between democracy and workers’ participation, bureaucratic unionism, and the interests of employers. These tensions were compounded by continuous conflicts between the centralized authoritarian government, the union bureaucracy, workers’ participation demands, and, especially, the resistance of the capitalist class. Moreover, the country witnessed conflicts between the dictatorship and intellectuals, artists, students, and professors, as well as severe repression of any opposition to the government. Perón expelled thousands of professors and students from universities, imprisoned many, and severely limited press and political freedoms. Even labour leaders who opposed him were exiled or imprisoned.

During Perón’s second term (which coincided with an economic crisis), conditions worsened. The death of his wife, Eva, added to his difficulties. In a confrontation with the Catholic Church, some parts of the army, incited by the church, attacked a large group of Perón’s supporters, resulting in numerous deaths. The retaliatory attack by Peronists on churches further escalated the situation. Soon after, in 1955, a bloody military coup overthrew Perón’s government and exiled him.

During Perón’s 18 years of exile, Argentina experienced two military governments and two civilian administrations. Despite the ban on any actions related to Peronism, labour organizations and political parties did not vanish due to the relative power the working class had gained. Throughout these years, the CGT remained intact, despite internal divisions between left and right-wing factions, and led various workers’ movements. Governments that followed Perón’s fall pursued economic policies based on market rationality and attracting multinational investments while implementing anti-labour policies and varying degrees of repression. Nonetheless, the workers continued to resist. A notable example occurred in 1959 when the government decided to privatize a large meat-processing factory. Nine thousand workers occupied and managed the factory for some time. Nearby factories and working-class neighbourhoods also supported the workers by staging blockades. Vieta explains that despite the harsh suppression of this broad movement, it marked a turning point in the history of the Argentine labour movement. Other labour movements against government policies continued into the mid-1960s, providing workers with valuable experiences and lessons.

In 1966, following another military coup supported by employers’ unions, multinational companies, and some right-wing leaders of the CGT, a harsh dictatorship came to power. This military regime lasted until 1973 and was faced with internal military coups and leadership changes. The labour movement was fragmented. The CGT leadership, along with right-wing Peronists, supported collaboration with the regime to obtain concessions, while the left-wing Peronists formed a new confederation called the General Confederation of Workers of Argentina (CGTA) and rejected any cooperation with the new regime. Perón, who was then living in Franco’s Spain, played both sides.

Part of the left-wing Peronists, advocating for Perón’s return, formed guerrilla groups. Several other guerrilla factions, including Maoists, Guevarists, and Trotskyists, were created by left-wing and communist forces. Secret worker gatherings, supported covertly by factory committees under harsh security conditions from both the government and the compromising unions, were held and, in many cases, managed to organize strikes. The military regime remained in power until 1973, amid a crisis marked by guerrilla warfare, repression, massacres, and numerous factory occupations by workers. Under pressure from Peronist and left-wing movements, the military regime eventually agreed to hold elections and allowed Perón’s party to participate – but not Perón himself.

The parliamentary democracy that followed the military dictatorship had a short lifespan, and after Perón’s return to Argentina, his third presidency began in 1973 despite his illness. A month before his return to power, the left-wing guerrilla group Montoneros (a Catholic Peronist group linked to liberation theology) killed the moderate and powerful leader of the CGT, who had been very close to Perón. This enraged Perón, who wept upon hearing the news, and in retaliation, many were killed and repressed. Using the relative economic improvement in the early 1970s, Perón implemented policies to improve the workers’ conditions and nationalized some banks and industries. As Perón’s illness worsened, his third wife, Isabel, whom he had met during exile in Panama, took on a more prominent role. She became vice president and, after Perón died in 1974, succeeded him and remained in power until 1976.

Argentina went through more coups, the brutal 1976 repression, a war with Britain over the Falkland Islands, and the re-establishment of civilian government in 1983, facing political and economic crises, hyperinflation, and unemployment. In 1989, a president from the Peronist party came to power and, by improving relations with Britain and moving closer to the United States, alongside addressing the crimes of the past military regime, fully accepted the International Monetary Fund’s structural adjustment policies in exchange for loans. The government sold the majority of state-owned companies, implemented austerity measures firmly, and pegged the national currency to the US dollar. Poverty, inflation, and unemployment created the conditions for a general strike in 1996. In 1999, a coalition of center-left and center-right forces brought a new president to power. However, the new government faced a continued severe recession, a debt of $114-billion, about one-third of Argentina’s GDP at the time, and the inability to pay it off. The government began drastically cutting economic assistance and public services. In 2000, the International Monetary Fund agreed to a package of loans worth $40-billion with very tough conditions. A general strike against austerity measures in 2001 complicated the situation further. In the parliamentary elections, Peronists took control of both houses. The government imposed stringent policies to prevent people from withdrawing their deposits from the banks, pension payments were interrupted, and another general strike led to the fall of the government. The International Monetary Fund also refused to disburse another part of the loan to Argentina.

Against the backdrop of these economic crises and the imposition of structural adjustment policies, the reduction of government spending to pay off foreign debts, the removal of import restrictions on foreign products, and the entry of multinational companies and foreign direct investment, with encouragement and support from the US government, many Argentine companies could not compete and went bankrupt, one after another. The labour movement, with its rich experience, stepped in on many occasions.

Some Conceptual Issues

In various parts of the book, Vieta elaborates on his theoretical concepts, which need some explanation: ‘Self-Management,’ ‘Co-management,’ and ‘Revolutionary Worker Cooperatives’:

The concept of ‘autogestion’ (self-management) used by the workers of occupied factories in Argentina, with its roots in Greek and Latin, is prevalent in Spanish, French, and Portuguese. Vieta notes the inadequacy of the common English equivalent of ‘self-management.’ Referring to Michael Lebowitz, Vieta points out that the English term emphasizes ‘self’ and individualism, which is contrary to the collective nature of the concept. Lebowitz prefers the term ‘congestion’ (co-management), which was used in the Bolivarian Venezuela under Chávez. Lebowitz suggests that this term conveys a sense of solidarity between the company and society as a whole and is based on the ‘trinity of socialism,’ meaning social ownership of production, social production organized by workers, and production to meet the needs of society, as opposed to the ‘trinity of capitalism,’ which is based on private ownership, exploitation, and production for profit. Nevertheless, while acknowledging this shortcoming, Vieta concludes that despite this ambiguity, the term ‘self-management’ can convey the social meaning intended.

While this discussion by Lebowitz is noteworthy, it should be noted that the term ‘co-management’ introduces another ambiguity and could be confused with the concept of worker participation in management (co-management, co-determination) in a capitalist system, which is by no means ‘worker control’ and reflects various degrees of ‘worker participation’ in management. The use of ‘co-gestion’ in Chávez’s Venezuela – as well as in Tito’s Yugoslavia – had meaning because the government had nationalized many companies, thus enabling co-management by workers.

Regarding production cooperatives, Vieta notes that the global cooperative movement has generally been reformist rather than revolutionary, and he defines cooperatives as a radical concept of self-management based on producing to meet life’s needs, economic justice through democratic organization of work by workers, and collective ownership of the means of production. He defines various aspects of such an institution based on definitions provided by different theorists: A worker cooperative is a productive institution in which labour employs capital, ‘work’ is the shared contribution of each member, control is based on labour, not investment, and revenues are in the common ownership of the members. Moreover, a cooperative is a voluntary association of workers who collaborate democratically, with each worker equally involved in management through worker boards or councils elected by the members.

It should be noted that the discussion here concerns only production cooperatives, not other types such as consumer, credit, or housing cooperatives, which exist in many countries, including advanced capitalist nations. The cooperatives discussed in the book are those that were formed through the direct action of workers, supported by unions, and independent of the government, not those established with government support or under the influence of the state. In fact, in Argentina, some cooperatives were created directly with government support as part of development policies and efforts to combat unemployment, and their nature is different.

It is also important to note that there is significant debate among Marxists regarding production cooperatives. Some see the idea that workers in a capitalist system could create a socialist space within the factory and ‘become their own capitalists’ or ‘own the means of production’ as delusional and misleading. On the other hand, some view worker cooperatives as a complete example of ‘worker control’ with socialist potential. Marx himself referred to production cooperatives and their importance. In his speech at the first International Workers’ Congress, after mentioning the great success of the ten-hour workday, he refers to an even greater success, namely the cooperative movement, especially cooperative factories, and calls it a ‘great social experiment’ – an experiment that shows that social production on a large scale can occur without the presence of masters and that the product of labour is not a tool for dominating or exploiting the worker.

However, he points out that, despite their importance, if production cooperatives remain limited in scope, they will never be able to confront the growing monopoly of capital, liberate the masses, or even alleviate their suffering, and must take on national dimensions. In volume three of Capital, Marx also discusses the separation of ownership from management and the distinct roles of managers and profit owners in cooperatives, suggesting that in England, after each crisis, the owners of bankrupt factories were employed as managers with meagre wages in their factories, which had now come under the control of creditors. Engels, in a footnote, refers to a case after the 1868 crisis, where a bankrupt factory owner, whose workers had taken over the factory and formed a worker cooperative, was employed as a salaried manager by his former workers.

Class-Struggle Marxism

In his theoretical discussions, Vieta places a strong emphasis on the view common in some Marxist circles referred to as ‘Class-Struggle Marxism’. This term distinguishes itself from Leninist-Bolshevik state-centred Marxism, economistic Marxism, and social-democratic reformist tendencies. This view, distancing itself from so-called ‘orthodox’ and ‘one-sided’ Marxism, avoids purely economic analyses of capitalism and property, focusing instead on the agency of the working class, its potential for resistance, class awareness and struggle against capital, and the growth and transformation of the working-class consciousness through praxis, with an emphasis on self-liberation from exploitation and alienation.

Although these theorists raise important aspects of class struggle and have enriched the dynamic transformation of Marxism, the term ‘Class struggle Marxism’ could be ambiguous. Was there ever a ‘non-class struggle’ Marxism? The analysis of the relationship between labour and capital constitutes a coherent whole, and maximizing one aspect minimizes the other. We have seen a focus on both aspects in Marx’s works (which I have addressed elsewhere). No doubt, coarse analyses of Marxism have not been uncommon, and if the intention is to distinguish from such analyses, why not attribute it to Marx himself, calling it ‘Marx’s Marxism’?

Vieta’s theorizing explores the diverse opinions ranging from early thinkers like Rosa Luxemburg and Gramsci to those of Lukacs on class consciousness, the first generation of the Frankfurt School, Walter Benjamin’s cultural theory, Marcuse, Fromm, Dunayevskaya, the French group ‘Socialism or Barbarism’, the Italian ‘Operaismo’ school, Autonomists, Marxist structuralists, and council communists like Anton Pannekoek and many others.

Factory Occupations, Reclamation, and Worker Management

When the economic crisis in Argentina deepened in the early 2000s, and many factories faced the risk of bankruptcy, industrial owners increased pressure and intensified the exploitation of workers, reducing production and extracting assets from their companies. In the absence of state support for workers, unions had few means of resistance. Workers, witnessing the collapse of their workplaces and having little chance of finding employment elsewhere, began to occupy factories, drawing on experiences from previous years. (For example, in 1964, just before the major military coup, about 11,000 factories with around four million workers had been temporarily occupied by workers.) By 2001, when the country’s economic collapse led to its inability to repay foreign debts, around 200 companies had been occupied by workers. With a relative improvement in economic conditions in the subsequent years, under the populist policies of the left-wing Peronist government, factory closures and occupations by workers dwindled but continued. Then, with the resurgence of neoliberal policies by the right-wing coalition government since 2015, the difficulties faced by these factories increased. However, they managed to survive thanks to their role and popular support.

In 2016, about 16,000 workers were employed in nearly 370 self-managed companies. The fields of activity of these companies included areas such as printing and publishing, media, metalworking, food, textiles, health, parts manufacturing, shipbuilding, construction, plastics, education, and tourism. In the early stages, these companies were mainly industrial, but gradually, with changing government policies, the number of industrial companies under worker control decreased, while the number of companies in other sectors of the economy, especially in the services sector, increased.

According to Vieta, despite their relatively small number, this is the largest movement in the world to transform capitalist factories into cooperatives – a movement that prevented factory closures, kept workers employed, preserved working-class neighbourhoods around factories, and improved the local economy. This movement has garnered popular support and has taught other workers that if they encounter similar circumstances, they can adopt such an approach. These factories created a national union called the ‘National Community of Self-Managed Workers’ (ANTA) as part of the General Confederation of Labour.

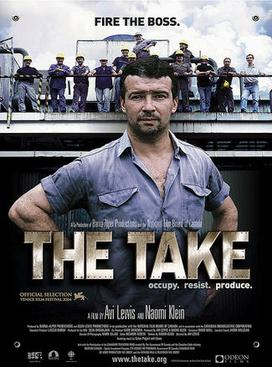

Interestingly, some of these seized and reoccupied factories by workers were so successful that their former owners tried to take them back by appealing to the judiciary and the police. In several cases, the public supported the workers, forcing the police to retreat. In other cases, workers managed to use the judiciary to defeat the employer and reclaim the factory. (Naomi Klein and Avi Lewis produced a fascinating documentary on this topic in 2004 for CBC Television – The Take.)

Apart from the many instances when governments, under the pressure of capitalists, used the judiciary and police to oppose workers’ actions, some governments, for various reasons – whether due to opportunism or a desire to reduce unemployment – supported these radical worker-led movements for factory recovery with worker management. According to Dean Reinstein, in 2004, the government institutionalized self-management in seized companies and, in exchange for financial and technical assistance to these factories, ‘depoliticized’ the workers’ actions aimed at preserving their jobs.

However, worker self-management was not always successfully implemented and often faced numerous challenges. The survival of seized factories by workers required legal recognition. Some had to accept the factory’s debts, while others had to negotiate with former owners to either buy the factory or rent it. Some factories could not survive in a highly competitive environment and had to shut down. Others returned to a capitalist model by employing wage workers, and some seized factories, in exchange for government subsidies, came under state influence and abandoned their radical political demands. In some cases, workers had to sacrifice by working longer hours for less pay, leading to a form of ‘self-exploitation.’

These factories needed additional investment, new machinery, and specialized staff, but raising funds and covering ongoing costs was not easy for many of these companies. Hiring new workers or specialists – except for those who were formal cooperative members – turned the cooperative into a capitalist company based on the exploitation of other workers by cooperative members. In some cases, this led to dissatisfaction among workers, especially more skilled ones, due to wage disparities. However, despite these issues and limitations, a significant number of worker-controlled companies in Argentina continued to survive successfully, thanks to their distinctive features.

Characteristics of Seized Factories and Institutions

Despite their diversity, self-managed production and service units shared several key characteristics:

- All these companies were either bankrupt or on the brink of bankruptcy, with their owners planning to shut them down or abandon them during the economic crisis. The workers took control of these factories to preserve their jobs.

- A very important characteristic was their small to medium size. While Vieta provides some general statistics on these companies, he does not delve into their size in terms of workforce, production capacity, or productive process (labour force and machinery). If we consider the statistics from 2016 (16,000 workers and 370 companies), each company had an average of about 43 workers and employees, indicating that they were mostly small units, with some medium-sized ones. In one case, a successful company had 300 workers and employees. (In comparison, Argentina’s total workforce in 2022 was around 22 million people, with about 7% in agriculture, 20% in industry, and 73% in services.)

- After the crisis, the workers’ ‘illegal’ actions had to take on a ‘legal’ form through various legal processes. Without government and judicial approval in the capitalist system, they could not continue to exist. One statistical table indicates that over 60% of these units received some form of support at various governmental levels – local, regional, or national.

- These companies operated within a capitalist system with specific requirements and limitations. On one hand, they had to maintain a democratic workplace organization, while on the other, to survive, they needed to operate within the timeframes and productivity requirements established by the market. To compete with capitalist companies, they had to invest in production capabilities and modernization. Vieta rightly describes this as a ‘dual reality,’ but he does not provide enough detail about it.

- These self-managed units were part of a larger network of labour organizations at the factory, regional, and national levels. The General Confederation of Workers (CGT) boasts over 1.5 million members. As mentioned, these self-managed units also established their national union as a component of the confederation.

- Another key feature was the close relationship between these factories, their unions, and working-class neighbourhoods, as well as the broad public support they received, without which they could not have continued to exist.

Challenging Neoliberalism?

The struggles of Argentine workers to save closed or threatened factories and their subsequent occupations, recovery, and management by the workers are undoubtedly one of the most significant cases of the global labour movement. But can this be applied universally to all industries and all circumstances? More importantly, as Vieta suggests (in the book’s subtitle), is it really a confrontation with neoliberalism? Without diminishing the importance of these massive actions by workers, the answer to both questions is, unfortunately, negative.

As mentioned earlier, these actions were limited to bankrupt or near-bankrupt factories of small or medium size. They cannot be extended to thriving, small, or medium-sized capitalist factories. Large industries, where the majority of workers are employed and which operate with substantial capital, even if they are bankrupt, cannot fall under this approach.

In the context of capitalism, these seized and worker-managed companies could not function independently of the harsh realities of the capitalist system, including time constraints for production and output. While worker cooperatives are less focused on maximizing profit and more on members’ welfare, they are still bound by market realities. This reality holds even for the most prominent worker cooperative in the world, the Mondragon Corporation in Spain. Despite its more democratic and fairer management system compared to other capitalist companies, Mondragon must still compete with them for its survival. Founded in 1956 by a Catholic priest in the Basque Country, Mondragon is now one of Spain’s largest companies and operates globally, benefiting from cheap labour in Central and South America. While wage differences exist, they are smaller than in capitalist companies, and many of their companies are managed by professional managers.

Without the approval of the ruling regime, government, and judiciary, these companies could not legally and permanently function. As noted in the case of Argentine seized companies, once the workers started operating these abandoned factories, their former owners sought to reclaim them through the legal system. In some cases, cooperatives had to take out loans to pay for land and infrastructure, or they negotiated leases. Sometimes they succeeded in winning court rulings in their favour against the original owners. In other words, without the final and official approval of the ruling regime, worker self-management was not possible. Also, without powerful, nationwide, and militant labour unions and broad public support – especially from the emerging middle class, intellectuals, and artists – workers in small, scattered factories would not have been able to occupy and manage their factories.

In summary, the occupation of a few hundred small and medium-sized companies cannot be considered a challenge to neoliberalism, especially in a country clearly under the dominance of neoliberalism, with a GDP close to $700-billion and a workforce of about 22 million. There is no doubt that wherever workers can gain ownership and control of the factory they work in, it is a valuable and commendable step toward strengthening the position of the working class and weakening that of capital. But to truly confront capitalism and neoliberalism, the capitalist state must be ‘seized.’ As Amadeo Bordiga, the first leader of the Communist Party of Italy and a collaborator of Gramsci, noted in 1920 during the height of the factory occupation movement, controlling the factory only matters when central political power has passed into the hands of the proletariat; ‘The factory is taken by the working class, not just by the workers of that factory.’

In conclusion, self-management and workers’ control by the ‘producers of wealth,’ in its true and comprehensive sense, can only be achieved when political-economic changes are directed toward transitioning from capitalism to socialism. This point I have addressed elsewhere in the context of “The (In)conceivability of ‘Real Worker’ Control Under Capitalism” and in The Transition from Capitalism: Marxist Perspectives. The Argentine experience reaffirms the idea that managerial workers’ councils emerge at the height of the capitalist crisis and disappear when the crisis is over.

Those who survive are usually small or medium-sized and remain under the constraints of capitalism. Without the support or approval of the political and legal systems, they cannot continue to exist. Genuine and widespread workers’ control, though limited, can only be realised through ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ socialisations during the peak of the transition from capitalism and beyond. In the era of capitalism, aside from small workshops that workers can take over in terms of ownership and management, the only viable pathway for the workers’ movement is through participation in management, co-management, or ‘co-determination.’ This participation becomes more advanced and radical as the working class and its democratic organisations strengthen.

A key lesson from the Argentine workers’ movement is the essential role of trade unions. Without unions at the factory, regional, and national levels, the Argentine working class could not have achieved such success. Although Argentine unions, like those in many countries, are bureaucratic organizations, their mere existence – especially compared to countries lacking a history of genuine trade unions – has enabled the working class to challenge the dominant capitalist system.

By establishing and strengthening independent trade unions through education and organisation, workers can, via workers’ councils that serve as participatory organs of unions, reach higher levels of participation, up to ‘co-management’ in proportion to their growing power. However, the call for workers’ councils and control – except in small workshops where workers may attain ownership and management – can be a misleading slogan. True self-management can only be realised through the development of a progressive system and state during the transition from capitalism and beyond. Under capitalist rule, especially with its globalised neoliberal nature, real workers’ control remains impossible. •

The original Farsi version of the review was published in Pecritique in June 2024.

References

- Amadeo Bordiga, (1920), “Towards the Establishment of Workers’ Councils in Italy” and “Seize Power or Seize factory?”

- Guido Di Talia, (2016), Political Economy of Argentina: 1880-1946, Springer.

- Ana Cecilia Dinerstein, (2007), ‘Workers’ Factory Takeovers and New State Policies; Towards the ‘Institutionalization’ of non-Governmental Public Action in Argentina, Policy and Politics, 35: 3.

- Bruno Dobrusin, “Workers’ Cooperatives in Argentina: The Self-administered Worker’ Association.”

- Dow Gregory, (1993), “Can Democracy versus Appropriability: Can labour-Managed Firms Flourish in a Capitalist World,” in Samuel Bowles, et.al, eds. Market and Democracy: Participation, Accountability, and Efficiency, Cambridge University Press.

- History of Argentina

- Maria Kabat, (2011), “Argentinean Worker-Taken Factories: Trajectories of Workers’ Control Under the Economic Crisis,” in Immanuel Ness and Dario Azzellini, (2011) Ours to Master and to Own: Workers’ Control from the Commune to the Present, Haymarket Books, Chicago, IL.

- Michael Lebowitz, (2005), “Construction co-management in Venezuela: Contradictions along the Path,” Monthly Review, 24 October.

- Karl Marx, (1864), Inaugural Address of the International Working Men’s Association.

- Karl Marx, (1984), Capital, Vol III, Progress Publishers, pp. 385-389.

- Pablo Pozzi, (1998), “Popular Upheaval and Capitalist Transformation in Argentina,” in Latin American Perspectives, 27.

- Saeed Rahnema, (2016), Transition from Capitalism: Marxist Perspectives, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Saeed Rahnema, (2022), “The (In)Conceivability of Real Workers’ Control Under Capitalism,” The International Labour and Working Class History, Cambridge University Press.

- John Restakis, 2010, Humanizing the Economy: Co-operatives in the Age of Capital, New Societies Publishers.