The ‘Twin Bill 5s’ and De-Democratization

Amid escalating US tariffs and annexation threats, Canada’s political leaders have invoked “national unity” as the guiding principle of their efforts to navigate the crisis (Carney, 2025, May 8). For much of Spring 2025, this rallying cry served more as a loose signifier than a coherent response to the pressures facing the country.

More recently, however, its meaning has come into sharper focus as governments across the country have seized on the tariff crisis to push through deregulatory reforms long sought by corporate lobbyists (Reuters, 2025).

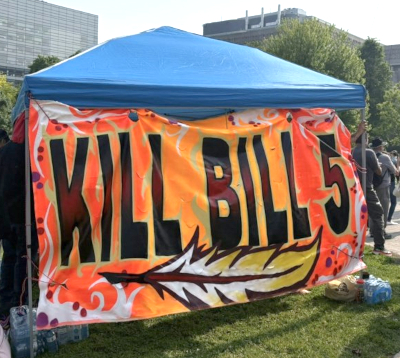

This trend is most clearly embodied in the “twin Bill 5s” brought forward by the federal and Ontario governments earlier this summer. Taken together, the federal Bill C-5, the One Canadian Economy Act (2025), and Ontario’s Bill 5, the Protect Ontario by Unleashing its Economy Act (2025), represent the most radical effort to date to dismantle regulatory guardrails.

Framed in the language of “economic necessity,” these measures offer a clear illustration of how de-democratization under advanced capitalism is primarily conditioned by the structural dynamics of the law of value. This underlying structure can be understood through Marx’s (1992 [1867]: 163) notion of “the fetishism of the commodity,” which reveals how the abstract nature of the commodity form under capitalism causes social relations to appear as relations between things.

Commodity Fetishism

The apparent fragmentation of capital, where isolated individuals and firms interact through abstract exchange with unknown others, generates a necessary illusion that reduces social mediation to relations between material objects. This fetishism causes market relations to appear natural and timeless, operating according to fixed laws, thus concealing an invisible form of domination embedded in the structure of this form of social life.

To understand these processes, it is therefore necessary to grasp the nature of the “ghostly objectivity” of capitalist relations, and the way it conditions actions by presenting a series of non-choices as free and self-determined (Lukács 1971 [1923]: 100).

As this logic becomes universal, it necessitates an inversion of democracy, requiring a strong executive that responds to market demands. Democratic institutions, including the regulatory state, are thus viewed as barriers to capital accumulation and are hollowed out to align political authority with market requirements.

Marx’s concept of commodity fetishism lies at the foundation of his theory of value and of the capitalist system more broadly (Rubin, 1972 [1928]: 5). It is rooted in the dual character of the commodity as both use-value and exchange-value, and in the fact that, in its concrete form, the commodity cannot express its social essence as a product of human labour.

The fetish is an historically specific product of capitalism; a necessary illusion that conceals the social processes behind commodity production and exchange, making them appear as objective forces beyond human control (Postone, 1993: 3). It obscures the fact that value is created through abstract labour, which strips concrete labour of its qualitative particularity, reducing it to a homogeneous social average. Measured in terms of socially necessary labour time, this abstraction conceals the social relations encoded within the commodity, enabling commodities to circulate on the market as equivalents (Marx 1992 [1867]: 128–130).

At the same time, this dynamic imposes an indirect form of compulsion on workers and owners alike, forcing them to conform to the temporal and quantitative demands of abstract labour (Postone, 1993: 3). Each individual or firm is independent of the whole and concerned only with their own interests, with no formal repressive mechanism regulating their activities (Rubin, 1972 [1928]: 6).

A baker selling bread, for instance, is not concerned with the specific value of her labour but with its social average relative to other commodities. She therefore must act as if value lies in abstract exchange relations, not in the concrete labour that produced the good.

Furthermore, when another baker at a bakery down the street purchases a high-capacity oven that enables them to produce twice as much bread, thus reducing the socially necessary labour time required to produce a loaf, our baker must respond by purchasing a similar technology or risk going out of business.

In this sense, fetishism is not a false or artificial consciousness but rather reflects an objectified reality in which “the process of production has mastery over man” (Marx, 1992 [1867]: 175). This invisible logic thus begins to assert itself with the force of a “regulative law of nature,” in the same way that “the law of gravity asserts itself when a person’s house collapses on top of him” (Marx, 1992 [1867]: 168).

This reordering extends across society, leading to what Lukács (1971 [1923]: 83) called “reification,” whereby the mask of the fetish is extended to all forms of social existence, including those belonging to the subject and their self-identity. As capitalist relations expand, all social relations come to appear as “supra-historical essences” such that the impersonal compulsion of the worker becomes the “fate of the whole society” (Lukács, 1971 [1923]: 90–91; 99). This shapes not only how individuals relate to one another but also how social power is organized and exercised.

The state under capitalism is one such example of a reified form. Under most bourgeois theories, the state is an autonomous entity, independent from economic and class relations, standing over and above society. However, Marxist theorist Nicos Poulantzas (2008 [1979]: 308) claimed that the state is an element of an integrated social totality under capitalism, operating as a “material condensation of a relation of forces between classes and fractions of classes,” rather than as a separate sphere.

The capitalist state is thus not a direct instrument of owners but rather exercises a “relative autonomy” to organize the capitalist class’s long-term interests, enabling it to present ruling-class compromises as rational, while concealing its role in enforcing them through the appearance of neutrality (Poulantzas, 2008 [1979]: 88). The sections to follow explore how the twin Bill 5s illustrate this dynamic.

Bill C-5, The One Canadian Economy Act

The One Canadian Economy Act (2025), proposes sweeping changes to environmental assessments and Indigenous consultation, accelerating approvals for private sector accumulation by narrowing the scope of scrutiny. The bill provides cabinet the authority to arbitrarily suspend existing regulations by designating projects for things like pipelines, mining, and ports as being in the “national interest” (Intergovernmental Affairs Secretariat, 2025, para. 2).

Thus, these projects are capable of being “advanced through an accelerated process” that “enhances regulatory certainty and investor confidence.” A new Federal Major Projects Office would be responsible for selecting those projects deemed to be of significant enough importance to warrant circumventing existing laws, including the Species at Risk Act, the Migratory Birds Conservation Act, and the Fisheries Act (Intergovernmental Affairs Secretariat, 2025, para. 10).

The bill thus grants unilateral power, with minimal oversight, to determine which laws private-sector developers will be legally permitted to avoid. Only once a project has been designated as “exceptional” does cabinet decide which laws will apply, meaning approvals will be provided before due diligence is possible. Although reviews can be triggered under existing legislation, Bill C-5 (2025) grants cabinet the ability to determine which of the recommendations it will require projects to adhere to.

Bill 5, The Protect Ontario by Unleashing its Economy Act

A similar logic animates Ontario’s Bill 5, the Protect Ontario by Unleashing Our Economy Act (2025), which likewise consolidates executive power while circumventing regulatory and democratic constraints. The bill is a comprehensive omnibus law that makes substantial changes to the province’s regulatory framework for project approvals.

The most significant reform is a new law enabling cabinet to arbitrarily designate “special economic zones,” exempting any business from provincial and municipal laws and by-laws. The bill allows the government to bypass the legislature and unilaterally select “designated projects,” letting companies operate without procedural oversight.

It empowers the province to override existing laws and by-laws by executive order, without parliamentary approval, creating ‘rules-free’ zones for capital accumulation. Bill 5 sets no criteria for project selection or public consultation, including with Indigenous communities. Its broad language allows the cabinet to name any person or group a “Trusted Proponent,” replacing public processes with secretive ones that privilege lobbyists.

Additionally, there are no limits on the size or location of special economic zones. Cabinet can designate zones anywhere in the province, on any scale, whether company-by-company or as large areas involving multiple private actors, including entire industries or communities (Bill 5, Sched. 9).

This approach is consistent with a surge in geographic areas carved out within nation states that are “freed from ordinary forms of regulation” (Slobodian, 2023: 3). They operate by “punching holes” in the state, constructing “zones of exception with different laws and often no democratic oversight,” functioning in accordance with the imperatives of capital (Slobodian, 2023: 3–4).

Legitimating Executive Rule Through Fetishism

In their defence of the bill, political officials made it clear that the main objective of the legislation was to circumvent regulatory guardrails and deliberative processes to meet the demands of private capital. National unity required capitulation to the forces of global competition, treated as a force of nature, like a hurricane or a flood, rather than a social mediation.

Prime Minister Mark Carney (as cited in Zimonjic 2025, para. 3) claimed that his government is “laser-focused on building a stronger, more competitive, and more resilient Canadian economy.” He argued that Bill C-5 is necessary because “in recent decades it’s become too difficult to build in this country” (Carney as cited in Vieira 2025, para. 4). The current regulatory regime, Carney (as cited in Vieira 2025, para. 4) continued, “is arduous, it takes too long, and is holding our country back.”

Echoing this urgency, Minister of Energy and Natural Resources Tim Hodgson (as cited by Prime Minister of Canada 2025, para. 10), declared that “in the new economy we are building, Canada will be defined by delivery, not delay.”

At the provincial level, Ontario Minister of Energy and Mines Stephen Lecce, expressed a similar commitment to removing barriers to capital investment. He argued that the Ontario Progressive Conservative government would

“…not follow the lead of governments of the past, who made empty promises about unlocking the potential of Ontario, who actually added red tape and delay to get projects completed, while capital fled away from the province into other resource economies” (Lecce, 2025, Apr. 29).

Likewise, Ontario’s Minister of Economic Development, Job Creation, and Trade, Vic Fedeli (as cited in Crawley 2025), emphasized the province’s commitment to rapid project delivery: “We want them [business leaders] to know that when they come to Ontario, it [capital] can be unleashed very quickly here.”

Canada and Ontario thus use two main rhetorical strategies to reduce social life to exchange relations. First, they naturalize capital’s relations, excluding analysis of labour exploitation. Terms like “competitiveness,” “innovation,” and “efficiency” take on neutral, eternal meanings, concealing their roots in historically specific social relations.

Business Council of Canada President, Goldy Hyder (2025: para. 23) in a testimony to Senate, illustrates the inevitability of the logic of capital:

“…they [owners of capital] would like to do it [invest] in democracies, and they would like to do it in Canada, but capital doesn’t have that requirement. Capital goes where it grows, and so as they look at Bill C-5, they see directionality, and they see good intentions and goodwill… you cannot legislate the deployment of capital. You can do everything else, but you cannot make anyone invest in your country. Your job – the job of legislators – is to create the conditions in which that can happen.”

The unambiguous message is that if investors can find better conditions for capital accumulation in non-democratic states, countries with institutionalized popular sovereignty will need to streamline these processes to increase the relative profit rate or risk losing investment and economic competitiveness. There is no direct compulsion, but the stakes of inaction are made starkly clear.

Second, based on this fetishized conception of regulatory democracy, such procedures are understood to hinder an adequate response to these dynamics. Institutional democracy becomes increasingly untenable, as it is portrayed as an obstacle to growth and investor confidence.

The logic of democracy is therefore inverted. Rather than ‘rule by the people,’ democracy becomes a question of how institutions can best respond to the supposedly law-like imperatives of capital. Popular institutions are hollowed out as a strong executive, with the flexibility to respond to the needs of investors, becomes the optimal mode of governance for this form of social life.

The Structural Logic of De-Democratization

As the twin Bill 5s illustrate, contemporary de-democratization tends to operate according to a structural logic grounded in the dynamics of abstract labour under capitalism. It works through an invisible form of compulsion that, unlike more overt forms of domination, do not rely on explicit coercion, but subtly shape behaviour by presenting social imperatives as neutral and rational (Postone, 1993: 3).

Democratic counterforces are thus eroded and undermined as a reflex to the objective forces of capitalist relations, which operate through the logic of the commodity form, as an invisible, yet concrete obligation (Lukács, 1971 [1923]: 52).

The fate of society as a whole mirrors that of our baker, mentioned above, who must purchase a high-capacity oven like her competitors if she is to survive in the market, regardless of her personal wishes. In this way, we are “ruled by abstractions,” as “thingly” relations come to dominate social life, presenting socially mediated objects as independent forces of nature (Marx, 1993 [1973]: 164).

This helps explain why the current crisis feels so intractable and why even some progressives have rushed to support these measures (Angus Reid Institute, 2025: 8). From within the perspective of capitalist appearances, acquiescing to the demands of the market seems rational. Reductions in the turnover time of resource development projects could hypothetically generate an increase in capital accumulation in these sectors. However, this is not a free choice; it is imposed by the “phantom” logic of capital (Lukács, 1971 [1923]: 83).

The only way to penetrate the illusion of fragmentation under capitalism, scientifically, is to grasp capitalist relations as a social totality that inscribes its dynamic, all-encompassing logic into the very structure of social life (Lukács, 1971 [1923]: 197). When the notion of totality is lost, reality appears as a series of disconnected phenomena, narrowing alternatives to isolated and one-sided choices, that deepen existing structures of domination.

By situating this issue within a perspective of the whole, the present crisis can be understood as a necessary contradiction within the logic of capitalism, at this moment of its historical development. This insight is especially crucial today, as the ongoing pressure to systematically erode institutional democracy in order to attract capital is likely to persist amid intensifying global competition. •

References

- Angus Reid Institute. 2025. “Bill C-5: Canadians Support Fast-Tracking Projects, But Conflicted Over Individual Elements of the Legislation.” Angus Reid Institute, June 26.

- Bill 5. 2025. Protect Ontario by Unleashing our Economy Act. Legislative Assembly of Ontario. 44th Parliament, First Session.

- Bill C‑5. 2025. The One Canadian Economy Act. House of Commons of Canada, 45th Parliament, First Session.

- Carney, Mark. 2025. “Bill C-5.” 45th Parliament, First Session. Hansard. House of Commons of Canada. May 28, 2025.

- Crawley, Mike. 2025. “Doug Ford’s Bill 5 Is Now Law in Ontario. Here’s What Happens Next.” CBC News, June 8.

- Hyder, Goldy. 2025. “One Canadian Economy Bill.” Debates of the Senate. 45th Parliament, First Session, Wednesday, June 18. Ottawa: Senate of Canada.

- Intergovernmental Affairs Secretariat. 2025. “One Canadian Economy: An Act to enact the Free Trade and Labour Mobility in Canada Act and the Building Canada Act.” Backgrounder, Government of Canada, June 6.

- Lecce, Stephen. 2025. “Protect Ontario by Unleashing Our Economy Act.” Legislative Assembly of Ontario. Hansard, 44th Parliament, First Session, April 29.

- Lukács, Georg. 1971. History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. Translated by Rodney Livingstone. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. (Original Publication, 1919-1923).

- Marx, Karl. 1992. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume One. Translated by Ben Fowkes. Introduction by Ernest Mandel. London: Penguin Books. (Original Publication, 1867).

- Marx, Karl. 1993. Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy. Translated with a foreword by Martin Nicolaus. London: Penguin Books.(Original Publication, 1973).

- McDowell, Tom. 2021. Neoliberal Parliamentarism: The Decline of Parliament at the Ontario Legislature. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Postone, Moishe. 1993. Time, Labour, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Poulantzas, Nicos. 2008. The Poulantzas Reader: Marxism, Law and the State. Edited by James Martin, London and New York: Verso.

- Prime Minister of Canada. 2025. “House of Commons Passes One Canadian Economy Act.” Press Release. Ottawa, ON. June 20.

- Reuters. 2025. “Canada’s Big Banks Push for Reforms in Ottawa to Confront Tariff Risks.” Reuters, February 28.

- Rubin, Isaak Illich. 1972. Essays on Marx’s Theory of Value, trans. Miloš Samardžija and Fredy Perlman, Detroit: Black & Red. (Original Publication, 1928).

- Slobodian, Quinn. 2023. Crack-Up Capitalism: Market Radicals and the Dream of a World Without Democracy. London: Allen Lane.

- Vieira, Paul. 2025. “Canada Introduces Bill to Speed Up Project Approval, Dismantle Trade Barriers.” The Wall Street Journal, June 6.

- Zimonjic, Peter. 2025. “Liberals Table Bill to Cut Trade Barriers, Speed Up ‘Nation-Building’ Infrastructure: ‘It’s Become Too Difficult to Build in This Country,’ Carney Says.” CBC News, June 6.