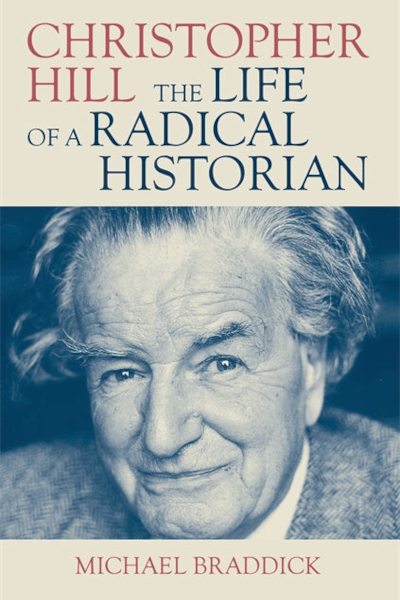

Christopher Hill: Life and Legacy of a Radical Historian

Christopher Hill looms large in the landscape of British Marxist historiography, perhaps the indispensable historian of the English Revolution for generations on the Left. His name evokes dusty paperbacks passed around student circles, dense arguments about base and superstructure, and crucially, the recovery of England’s own revolutionary tradition – a past “turned upside down” by the common people. Michael Braddick’s new biography, Christopher Hill: The Life of a Radical Historian, offers a timely opportunity to reassess this complex figure, a man whose life spanned the tumultuous twentieth century and whose work sought to make sense of history, not as a pageant of kings and queens but rather as a terrain of class conflict and ideological struggle.

Braddick charts Hill’s journey from the earnest, respectable Methodism of his York upbringing – a background that, as Hill himself acknowledged, instilled a certain moral seriousness and perhaps a nonconformist suspicion of established power – into the heart of Marxist thought and the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). This wasn’t merely an intellectual conversion. It was forged in the crucible of the 1930s: the great betrayal of Ramsay MacDonald, the grinding reality of the Depression (starkly visible in Hill’s hometown, where Rowntree found 30% living below the poverty line), the rise of Fascism, and the apparent bankruptcy of bourgeois liberalism in the face of global crisis.

Formative Years

As Braddick highlights, drawing on Hill’s early notes and intellectual formation, Hill’s Marxism was infused with a deep engagement with literature and a search for personal authenticity. Reading Eliot, Lawrence, Auden, and Joyce, the young Hill grappled with the alienation endemic to modern bourgeois culture. Marxism, particularly its humanist strands accessible through texts like the then-recently published German Ideology, offered a framework not just for understanding the economic contradictions of capitalism but also the “dissociation of sensibility,” the rupture between individual feeling and social expectation. It promised a future where individual and collective flourishing could be reconciled. This perspective, Braddick suggests, was as crucial to Hill’s intellectual DNA as the more familiar economic critique found in Capital.

Hill joined the CPGB in 1936 after a formative visit to the USSR, remaining a member until the shattering revelations and events of 1956-57 forced a painful break. Braddick navigates this difficult period, including Hill’s sometimes frustratingly opaque relationship with Stalinism (his 1953 encomium to Stalin, which he later regretted, remains a significant blot) and the intense internal battles within the CPGB Historians’ Group. He shows a man committed to the Party as the vehicle for change, even while wrestling with its dogmas and the crushing weight of democratic centralism. The biography details the MI5 surveillance, the casual assumptions of the security state, and the professional risks Hill ran, reminding us of the chilly climate of the Cold War academy for committed radicals.

Hill’s great contribution, of course, was to wrench the study of the 17th century away from Whiggish narratives of constitutional progress or purely theological explanations of the “Puritan Revolution” (a term he used interchangeably with The English Revolution). He insisted that ideas, even religious ones, took root and gained force because they resonated with specific class interests and material conditions. Purtainism’s emphasis on hard work, thrift, and individual conscience provided the moral and intellectual scaffolding for the emerging bourgeois attack on the old social order, ultimately paving the way for capitalist development.

But the Revolution also provided space for an explosion of radical thought and practice among groups like the Levellers, Diggers, Ranters, and Seekers, sparking what Hill referred to as the “revolution within the revolution.” Hill’s study of popular struggles in works like The World Turned Upside Down (1972) became talismans for the New Left and counter-culture, offering a usable past, a vision of an England teeming with radical possibilities that spoke directly to the aspirations of 1968 and beyond.

Braddick, himself a historian of the period, presents an “intellectual life” rather than an intimate biography, respecting Hill’s notorious personal reserve. While diligent in tracing the development of Hill’s thought through his writings and surviving papers, the portrait sometimes feels inattentive to the political urgency that drove Hill; the focus on the intellectual journey and the careful exegesis of texts occasionally risks downplaying the raw commitment and the political project inherent in Hill’s historical practice. Readers may wish for a sharper engagement with the organizational history of the CPGB or a more sustained critique of Hill’s compromises with the establishment, particularly during his time as Master of Balliol (1965-78) – a period Braddick covers with attention to Hill’s modernizing, if sometimes ambivalent, role during the era of student rebellion.

The biography meticulously documents the later attacks on Hill – the rise of revisionism, which sought to deny the revolutionary character of the 17th century and downplay class conflict, and the politically motivated accusations during the Thatcherite culture wars, culminating in the absurd espionage claims peddled by Anthony Glees. Hill, by then, represented a particular kind of engaged public intellectualism the Right wished to marginalize.

Hill’s Legacy

What is Hill’s legacy for the Left today? Braddick affirms Hill as a figure of immense intellectual integrity and moral seriousness whose life demonstrates the profound connection between historical understanding and political commitment. Hill showed that England possessed its own revolutionary tradition, grounded not just in abstract ideals but also in the material struggles of ordinary people. His insistence on totality – connecting economics, politics, culture, and individual experience – remains a vital counterpoint to fragmented, depoliticized approaches to the past. Yet, his story is also a cautionary tale about the perils of party loyalty in the face of indefensible actions and the difficulties faced by intellectuals navigating the relationship between academic rigour and political strategy.

Reading Braddick reminds us why Hill mattered – and still matters. In an era demanding historical perspectives on the recurring crises of capitalism, state power, and cultural hegemony, Hill’s determination to understand the past as a means to shape a better future remains profoundly relevant. His work is a testament to the power of history written from the standpoint of struggle. This solid, scholarly biography provides the essential map to that life and work. •