Trump’s Tariffs: Fake Problems, Fake Solutions

Trump is mad. Mad at the world. Mad at anyone who challenges him. Mad in his actions. Tariffs, a tax on goods coming into the US, are Trump’s weapon of choice to “make America great again.”

Tariffs are Trump’s magic bullet to end fifty years of the US importing more than exporting, bring manufacturing jobs back, and serve as a cash cow to shift a greater share of the burden of running the American Empire onto other countries, friend and foe alike. The far right has been successful in many countries mobilizing popular frustrations. But it has no program that can deliver on its promises.

This has been especially clear with Trump’s on-again, off-again, who-knows-again tariffs. which are based on a series of misconceptions and mis-directions. We cite a few here.

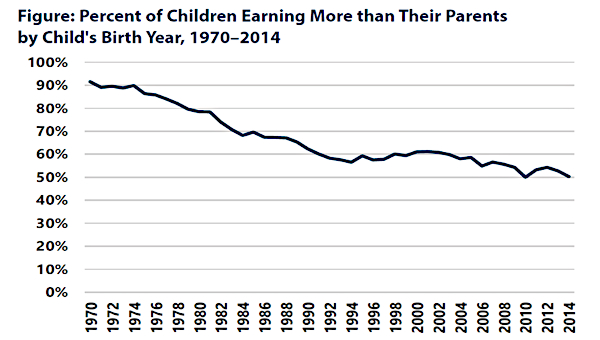

• Far from the import-export deficit being the main cause of the deterioration of working-class lives over the past five decades, the more momentous factors have been home grown.

It is not the imports from abroad that have most undermined the lives of American workers. Focusing on imports diverts from America’s far larger home-grown increases in inequalities and insecurities: the absence of universal health care, barriers to a quality education, lack of affordable housing, failure to address the environmental crisis, a deplorable record in defending union rights.

• Far from the US trade deficits signifying the ‘advantage’ that other countries take of the US, they reflect the special privileges that come with the US overseeing global capitalism.

Countries can generally only import more if they match this with exports. Otherwise, confidence in their currency and hence its value declines. This raises import prices and brings a fall in imports (think of the impact of a reduction in the Canadian dollar from $.90 US to $.75 US). The one exception to such disciplinary pressures is the US.

In every year since 1976, the US ran trade deficits, yet its economy rolled comfortably on and confidence in the dollar persisted. Other countries were happy to get dollars in exchange for their trade surpluses because the US dollar was universally accepted, safe despite occasional fluctuations, and a greater safeguard than their own currencies in times of crisis. That the US could access the products of lower-cost labour abroad by essentially printing dollars has been a privilege, not a cost.

• Far from foreigners paying the tariff, domestic consumers and business will pay the tariff via the higher price while the government pockets the value of the tariffs.

After much bravado, Trump – facing a menacing possible mini rebellion once consumers confronted the sticker shock produced by tariffs – hastily retreated, implicitly confirming the obvious: US consumers, not Chinese producers, would pay the tariff. The once ‘permanent’ tariffs have morphed into a negotiating tool for blackmailing other countries and a weapon in the cold war with China.

• Tariffs are neither good nor bad in the abstract.

Free trade (no tariffs or other barriers) leaves private corporations ‘free’ to move jobs wherever they like. Tariffs can be a check on this. But to significantly restructure the economy, tariffs alone will, at best, have a minor impact. This isn’t only because of Trump’s incoherent approach, likely retaliation against US exports and the chaos of trying to rejig supply chains as was revealed during COVID. It’s that even the stunningly high tariffs on China won’t lead to replacing Chinese imports with American goods, but will rather turn imports to sourcing from other low-cost producers.

• Sobering lessons can be learned from the iconic auto sector.

In the mid-eighties, the US successfully pushed Japanese auto companies to shift their exports to new plants in the US. But left to decide where to go, the Japanese transplants chose the non-union south, rather than where plants were closing. With brand new facilities, no pension legacy costs, and no unions, they caused even more havoc in the US mid-west and were soon significantly influencing the industry’s labour standards.

Today, another transition is occurring in auto: that to EV’s. There are three job concerns here. First, the US market for new vehicles is relatively flat while productivity marches on. Second, EV’s require less labour per vehicle. Third, the US transition has badly stagnated and still has no convincing strategy for protection of workers. China, in contrast, has come from virtually nowhere to produce some 75% of global vehicles (roughly the same share the US had of global auto production at the end of the 1950s). The bottom line is that auto will no longer be the job creator of old. A critical question is whether a portion of the facilities, skills, and supplier networks can be transferred to other products?

• Manufacturing jobs were once considered good jobs. This is less obvious today.

In the 1970s, wages in US manufacturing were about 50% above the average wage in the economy. Today (March 2025), average hourly wages in manufacturing (and working conditions) are slightly below the overall average wage: $34.42 vs $36. And average wages in auto, once abour 50% higher than in the overall economy, now lag the economy average at $32.88 (top rates in the auto majors are higher but starting rates are significantly lower). The key factor here lies in the existence and strength of unions. There is no basis for Amazon wages to be a third of that of autoworkers except for the union factor.

• Manufacturing is, nevertheless, crucial because of the productive capacities it brings.

This is especially clear regarding the environment. Fixing the degradation of the environment will mean transforming everything about how we work, travel, and live. Factories and offices will require modified machines and equipment; homes and appliances will need refurbishing, transportation and other infrastructure will require renewal and expansion. All this will necessitate expanding our manufacturing and dealing with a likely shortage of jobs to match needs. In this context, closing potentially productive facilities world be a social crime.

Such a project is an alternative in need of authors. One inspiration is the conversion of facilities carried out during WWII when 40% of US production served the war effort. The technical capacity for planning a peace-time effort is greater today and the need as existential as it was then. Many will no doubt write off such ambitions as ‘utopian’. But what can be more utopian (in the negative sense) than to leave our futures to the fragmented decisions of profit-driven corporations and reduce public policy to Trump-like tariffs? •

The Socialist Project regularly publishes pamphlets and shorter flyers on current issues. We welcome suggestions for further publications as well as questions and comments.