Trump’s Tariff Policy: Disciplining Capital by Granting Exemptions

An important motivation for US President Trump’s tariff escalation is often overlooked: tariffs serve Trump as a domestic and foreign policy instrument of power. The instrument of power consists of granting tariff exemptions for good behavior and denying such benefits or imposing even higher tariffs for lack of support or even opposition to Trump. Thus, the granting of tariff exemptions is part of a general drive to silence opposition. The article first discusses the contradictory nature of the officially stated goals of Trump’s tariffs, then describes the policy of granting exemptions to foreign nations and domestic companies in Trump’s first presidency, and presents some evidence for a repeat of such favoritism in the second presidency.

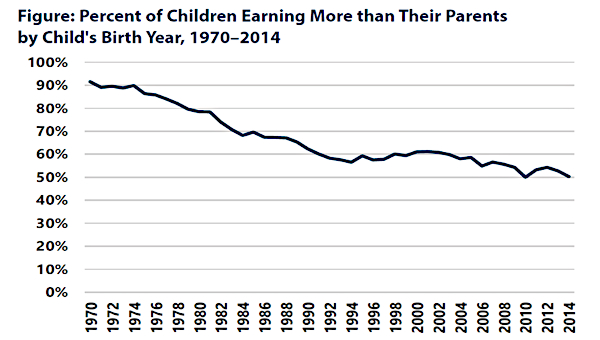

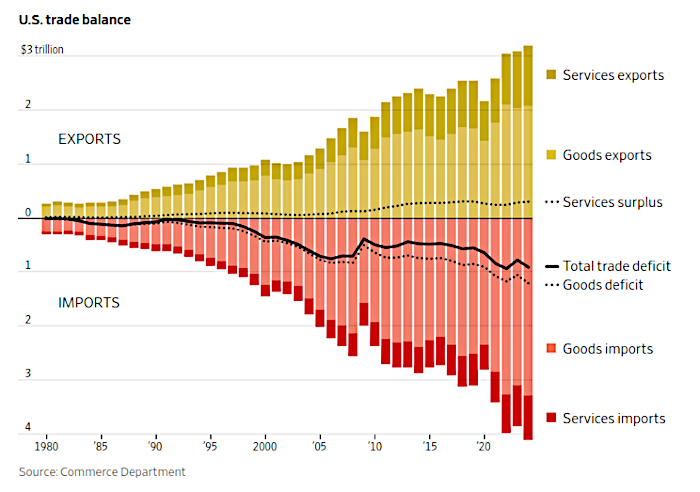

In his second term, President Donald Trump is raising tariffs on imported goods faster and higher than in his first term. These tariff increases violate not only the rules of the World Trade Organization and the free trade agreements ratified by the US (especially those renegotiated with Canada and Mexico during his first term) but also violates the US Constitution, which gives Congress, not the president, the power to set tariffs. Trump justifies the tariff increases on the grounds of national security, which has allegedly been threatened by years of high trade deficits. The tariffs could both strengthen domestic import-substitution industries and boost the export economy. The latter is possible because the size and scope of the tariffs could be used as a bargaining chip with trading partners to lower their trade barriers. In addition, tariffs are a good source of revenue that can be used to reduce income and corporate taxes.

These three publicly known goals have been the subject of critical commentary in pro-business media and economic policy circles for some time. The sharp stock price declines immediately following the announcement of the sweeping tariff increases on April 8, 2025, and the subsequent sharp price fluctuations despite the 90-day pause before the tariffs take effect for all countries except the People’s Republic of China, have prompted even Trump supporters to publicly criticize his approach. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that Trump will stick to his tariff policy and, according to my thesis here, for a reason that has received little attention so far: tariffs serve Trump as a domestic and foreign policy instrument of power. The instrument of power consists of granting exemptions from the tariffs in the case of good behavior and denying such benefits or imposing even higher tariffs in the case of lack of support for Trump or even opposition. It is a strategy to make the business community compliant. This behavior has already been documented for his first term and is described in more detail below.

First, however, two of the Trump administration’s stated tariff policy objectives are examined for their compatibility and the associated political risks for Trump: Revenue and market liberalization.

Conflicting Objectives:

Customs Duties as a Source of Revenue and as a Bargaining Chip

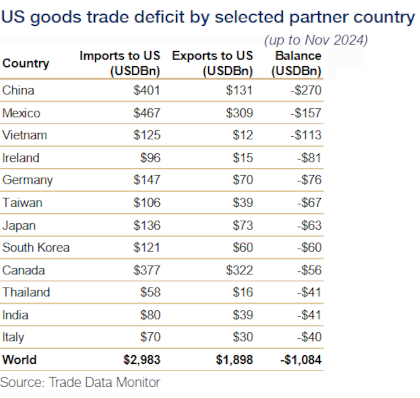

Tariff revenues should allow the Trump administration to cut corporate taxes. The fact that import tariffs are considered regressive from a distributional perspective (Baker, 2025) is unlikely to be a problem for the billionaires in the Trump administration. More problematic is the price-gouging effect of tariffs that mainstream economics assumes. A still-significant share of imports from the People’s Republic of China, and presumably a large share of imports from Vietnam and similar countries, are consumed by the low- and middle-income US population, which means that the majority of the population will be affected by price increases. Luxury goods, on the other hand, tend to be imported from Europe and are consumed by people who are better off financially. This demographic, which tends to be more politically active, is therefore also affected by import tariffs. Since Trump owes his electoral success not least to his promise to reduce the inflation of the last years of the Biden administration, he cannot be indifferent to the inflationary tendencies of his tariff policy for electoral reasons.

The threat of import tariffs to persuade trading partners to open their markets makes perfect sense in terms of power politics. The primary target is not the partner’s tariffs, which have already been significantly reduced in numerous trade rounds, but rather non-tariff barriers to trade. Such a strategy is usually successful with smaller countries, but the outcome with larger trading partners is more uncertain. In particular, the Trump administration is demanding that the European Union refrain from controlling data flows, taking antitrust action against large US IT companies, and imposing a global minimum tax on transnational corporations (Berg, 2025). Given the differing trade interests and vulnerabilities of EU member states to US threats, a partial success of Trump’s strategy cannot be ruled out from the outset. However, by verbally insulting the EU and most European countries at the same time, Trump strengthens the construction of a European identity, which makes it easier for the EU to stand united against American threats (Wieslander & Blomqvist, 2025). This also applies to the central target of US trade policy, the People’s Republic of China. China is attempting to replace the technological leadership of the United States with policy measures that Friedrich List proposed for catching-up economies in the 19th century. The Trump administration argues that China must be prevented from doing so. Trump’s verbal aggressiveness makes it easier for China’s ruling state party to persuade the population to sacrifice in defense of national sovereignty (Yuan, 2025).

Already in his first term, Trump failed in his attempt to dissuade China with his punitive tariffs from its ambitious high-tech program. This was very expensive for the American taxpayer, as Trump generously compensated the agricultural companies affected by the Chinese countermeasures with transfer payments (GAO, 2021a). Although Trump’s first-term tariff policy, which was largely continued by the Biden administration, initiated a process of reducing import dependence on China (from 21.6% to 13.4%, 2017-2024), this policy did not lead to a change of course in China (which is now the world leader in five out of 13 key technologies)1 or to a reduction in the US trade deficit with China ($361-billion US, 2024). The People’s Republic of China is likely to be even better prepared for Trump’s tariff policy in his second term. The US share of its exports will fall from 19% in 2017 to 14.7% in 2024. Food dependence on the US has also decreased (soybean imports fell from 40% to 18%, 2016 – 2024). Chinese currency reserves are now less tied up in US government bonds, more than a quarter of Chinese exports come from foreign-owned factories, and a transnational payment system independent of the US is being established (Greene, 2024). By contrast, the US is a relatively insignificant supplier to China in almost all major product categories, with the exception of jet engines and, to a limited extent, soybeans.

As Lawrence Summers, former Treasury Secretary under President Obama, has convincingly shown, the two economic goals are only partially compatible. If tariffs are to serve as a sustained source of revenue, then they cannot also serve as a bargaining chip for market opening.

This raises the question of whether the publicly stated objectives cover the full range of motivations for the policy of high tariffs.

Exemptions for Campaign Donors in Trump’s First Term

On July 10, 2018, the Trump administration announced that it would impose tariffs on $34-billion worth of goods imported from China, with an initial average tariff rate of 25%. Three consecutive extensions of punitive tariffs on Chinese goods over the next 14 months resulted in $550-billion of imports being subject to an average tariff rate of around 20% in 2018.

At the same time, a tariff exemption process was established for China that was fully controlled by the executive branch. The criteria for granting exemptions were specified in the US Federal Register: 1) if the application of the tariff to a product would significantly harm the interests of the United States, 2) if no substitute products are available in the United States or in third countries other than China, or 3) if the products are not considered strategically important for China (Lighthizer, 2018).

A company had to submit a separate application for each product for which it sought an exemption, and other companies could also submit applications for the same product. The Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) was the sole arbiter of individual exemption requests. If an exemption was granted, all companies importing the same product were exempt from the duties. Exemptions were retroactive to the date the tariffs were imposed and were granted for one year with the possibility of extension. The USTR did not begin to publish its decisions until about a year after the tariffs were imposed. The decisions could not be appealed (Hufbauer & Lu, 2019).

There is some anecdotal evidence of political influence in the literature. For example, one company’s duty exemption requests were granted even though the third criterion for duty exemption, non-strategic goods, was not met. However, according to public documents, this company had spent $40,000 lobbying the USTR. CEOs of major companies have appealed directly to Trump. Tim Cook of Apple was able to obtain an exemption, presumably with the promise of a large investment in the United States (Brown, 2019). In October 2019, the Assistant Inspector General for Audit and Evaluation at the Department of Commerce pointed out the possibility of undue influence on the decision-making process (Rice, 2019). Early in Biden’s presidency, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) examined selected exclusion cases and found inconsistencies in agency reviews (GAO, 2021b).

The anecdotal evidence is supported by a quantitative study by Fotak et al. (2025). This study documents the USTR’s favoritism toward donors to the 2016 campaign of Donald Trump and the Republican Party. In their sample of 7,015 USTR decisions, 1,022 ultimately approved applications came from firms with larger campaign contributions and higher lobbying expenditures, compared to 5,993 ultimately denied applications. Campaign contributions to influential politicians (e.g., those who sit on key Senate committees) had a greater impact, as did hiring lobbyists who had previously or subsequently worked for the Trump administration.

The study also controlled for the following factors. Neither a desire to protect companies in Republican-dominated states from Chinese retaliatory tariffs nor state-level free trade ideology changed the results of their regression analyses. In addition, using an event study methodology, the study found that the approvals were associated with an abnormal return of about 55 basis points in the 5-day window around the announcement. The increase was smaller for companies that were known to be more likely to receive an approval due to their proximity to the Trump administration. For these companies, a successful approval was already ‘priced in’ to their stock market valuation. The authors conclude that the preference for companies favorable to Trump was not hidden.

However, the study also found that applications that met the criteria set by the USTR were more likely to be approved, suggesting that the system was not fully politicized (Fotak et al., 2025, p. 3).

Extortion of Trading Partners in the Second Term

By 2018, punitive tariffs were already being used to enforce not only traditional trade policy demands but also other demands, such as limiting illegal migration across the Mexico-US border (Karni et al., 2019).

In his second term, the call to close the border is joined by demands to stop illegal drug smuggling into the US and to deliver the contracted amount of water from the Rio Grande (Samuels, 2025a). Trump proudly boasts that many countries called in at the last minute to sign an agreement: “I’m telling you, these countries are calling us up, kissing my ass.”

President Trump says he is open to lowering or waiving the global 10 percent tariff he imposed on US imports as part of his “reciprocal” tariff regime. But he says that will depend on concessions offered to the US by its trading partners in a flurry of talks that officials claim now include “over 75 countries.”

Peter Navarro, the Trade Representative in Trump’s first term and now Trump’s official adviser on trade issues, is one of the key masterminds behind a high tariff policy and an agitator for higher tariffs, particularly against the People’s Republic of China. While it appears that Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has gained weight over Navarro in the Trump administration following the announced 90-day general pause on punitive tariffs (Politi et al., 2025), it is unlikely that Trump will drop Navarro. Navarro serves as Trump’s bad cop in negotiations with trade partners, so that he can play the role of good cop (Gangitano & Weaver, 2025).

Silencing the Opposition in the Second Term

As early as January 2025, Democratic Senators Elisabeth Warren (Massachusetts) and Tina Smith (Minnesota), in a letter to Secretary of Commerce-designate Howard Lutnick and Trade Representative Jamieson Greer, expressed their suspicion that Trump’s trade officials would once again hand out “exemptions in arbitrary, unfair, and opaque backroom deals” (Brown, 2021). This suspicion was quickly confirmed.

Trump explained that he was considering exempting some US companies operating in countries affected by his so-called reciprocal tariffs from the announced tariffs: “There are some that have been [hit] hard. There are some that, by the nature of the company, get hit a little bit harder. And we’ll take a look at that.” Possible exemptions would be decided “instinctively”: “You almost can’t take a pencil to paper. It’s just really more of an instinct I think than anything else” (Chavez, 2025).

Apple and other US IT companies that manufacture in China have already been exempted, at least temporarily, from the exorbitant tariffs on smartphones, computers, and other electronic devices (Samuels, 2025b).

Trump’s lord-of-the-manor style is not limited to tariff policy. Even in his first term, he departed from the public restraint of presidents toward individual companies and pilloried them. Fearful of his large, radicalized following, the boards of directors of major corporations are restrained in their criticism of Trump, if they have any. They do not seem to object to crony capitalism. The abandonment of rules in foreign policy is thus reflected in domestic policy.

However, in the face of the sharp drop in stock and bond prices following the announcement of high punitive tariffs, some prominent financial players have let their guard down and publicly voiced criticism. In doing so, they contributed to the announcement of the 90-day pause (Kowitt, 2025). It remains to be seen to what extent they will have to pay for this success with subsequent sanctions from Trump. In any case, the outcome of Trump’s tariff war is uncertain, as further escalation is just as conceivable as symbolic concessions from trading partners that persuade Trump to impose moderate tariffs. However, given his claim to power, it is certain that he will continue to use the granting and withdrawal of tariff exemptions to discipline the US business community. There is no reason to believe that corporate America will stop this march toward 21st century crony capitalism with fascist attributes. •

References

- Baker, D. (2025). Donald Trump Is Confused: Tariffs and Taxes. Center for Economic and Policy Research.

- Berg, A. (2025, February 26). Trump’s tariffs – how should the EU react? Centre for European Reform.

- Brown, C. (2019, November 5). Trump’s Puzzling Tariff Exclusion Process. Axios.

- Brown, C. (2025, January 16). Warren against tariff "loopholes" for big biz. Axios.

- Chavez, S. (2025, April 9). Trump says he would consider exempting some US companies with operations in tariff-hit countries. Financial Times.

- GAO – United States Government Accountability Office (2021a). US-CHINA TRADE USTR Should Fully Document Internal Procedures for Tariff Exclusion. GAO-21-506.

- GAO – United States Government Accountability Office (2021b). USDA Market Facilitation Program. GAO-22-468.

- Gangitano, A. & Weaver, A. (2025, April 10). Navarro approach rubs GOP the wrong way amid trade war. The Hill.

- Greene, R. (2024). China’s Dollar Dilemma. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Hufbauer, G. C. & Lu, Z. (2019). The USTR Tariff Exclusion Process: Five Things to Know About These Opaque Handouts. Peterson Institute for International Economics. (2019).

- Karni, A., Swanson, A., Shear, M. D. (2019, May 30). Trump Says US Will Hit Mexico with 5% Tariffs on All Goods. The New York Times.

- Kowitt, B. (2025, April 12). Wall Street Just Learned How to Influence Trump. Bloomberg.

- Lighthizer, R. E. (2018). Procedures to Consider Requests for Exclusion of Particular Products from the Determination of Action Pursuant to Section 301: China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices. Federal Register Document 2018-14280.

- Politi, J., Pollard, A. & Fontanella-Khan, J. (2025, April 11). Scott Bessent, the Treasury secretary shaping Trump’s trade war. Financial Times.

- Rice, C. N. (2019). Information Memorandum for Secretary Ross. Management Alert: Certain Communications by Department Officials Suggest Improper Influence in the Section 232 Exclusion Request Review Process Final Memorandum No. OIG-20-003-M, October 28, 2019.

- Samuels, B. (2025a, April 11). Trump threatens Mexico with additional tariffs in water dispute. The Hill.

- Samuels, B. (2025b, April 13). Lutnick: Smartphone tariff exemptions are temporary. The Hill. https://thehill.com/business/5246743-lutnick-smartphone-tariff-exemptions-temporary/

- Wieslander, A. & Blomqvist, L. (2025). Europeans are responding to Trump by rallying around the EU flag. Atlantic Council.

- Yuan, L. (2025, April 12). Trump Showed His Pain Point in His Standoff with China. New York Times.