Climate Finance and the Limits of Market Fundamentalism

On December 18, 2024, we spoke with Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood, a senior researcher at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), a research institute that contributes to the debates across Canada by providing research and analysis for policymakers, activists, and the general public. Mertins-Kirkwood champions pro-public solutions to tackle the climate crisis by financing public goods instead of offering incentives to private firms. He responds to the recent announcement at COP29 that Canada will dedicate $1.48-billion to mobilize climate-focused investment in vulnerable regions of the world by using public money to ‘derisk’ the private sector in an approach known as blended finance.

This interview is part of a series with the Blended Finance Project, a group of unions, non-governmental organizations, and academics concerned about the Canadian government’s embrace of blended finance. We argue that blended finance is merely the latest iteration of the privatization and financialization of foreign aid, and we seek to promote more equitable public alternatives. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Susan Jane Spronk (SJS) and Karen Spring (KS): Why do you think that blended finance and other so-called innovative finance are inadequate mechanisms to address the current climate crisis in Canada and globally?

Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood (MHK): There are many reasons. The climate crisis is complicated and requires a balance of considerations. Instead of focusing efforts on making the ‘green’ economy most profitable, we should focus on reducing how much energy we use, producing energy more sustainably, and ensuring that we are not leaving workers and communities behind. We cannot just hope that the market will solve the problem. It is unlikely to do so.

For example, the Canadian Infrastructure Bank and the Canadian Growth Fund are two federal government initiatives premised on the hope that for every dollar of public money we spend, we will supposedly leverage $2, $3, $5, $10 of private capital to advance public goods. And that has never panned out because at the end of the day, we are just asking and hoping that the private sector will deliver public goods. But private investors will not do that unless they think they will make a profit. Some of these projects are either not inherently profit-making, or they require long-term investments that might make a profit eventually but not in the short term.

To make matters worse, under the current market model, the state provides subsidies and other support for private investments that would have been made anyway. For example, the government might provide a 40% tax credit, but the company was going to build that wind farm anyway, and they pocket the extra 40%. That is not a very good use of public money.

Another big issue when it comes to climate is that a lot of these initiatives around blending finance are very much a “carrots only” approach that try to create more attractive investments for private investors. But this approach does not grapple with the root problem: we must stop using fossil fuels. Trying to incentivize the private sector does not deal with that half of the equation. Trusting the private sector to be the main leader on decarbonization or on delivering public goods is simply not going to work.

SJS and KS: At the COP29 in November 2024, the Canadian Minister of the Environment and Climate Change announced that Canada would invest $1.48-billion in a finance platform with the help of FinDev Canada and the Green Climate Fund to mobilize climate-focused investment in vulnerable regions of the world, but particularly in developing countries. Is Canada taking the right approach with this announcement? If so, why? And if not, why not?

HMK: The most fundamental principle that we should establish up front is that loans and profit-seeking investments are not the same thing as aid. The government calls it climate finance, but really, it is another way to make money. And that is problematic for several reasons. Similar to Canada, the investments that need to be made in the Global South should not be primarily about profit. We need public goods we can rely on, such as clean water, clean energy, and public services like healthcare and education. On the other hand, private investors are saying, “We can make a lot more money in mining or energy production, so that is where we are going to put our investment dollars.” Fundamentally, there is a mismatch in priorities regarding the goals of international aid, development finance, and climate finance should try to accomplish and the goals that investors and the private markets are seeking in these relationships.

SJS and KS: How would you evaluate Canada’s approach in involving the private sector and successfully addressing key climate issues in Canada? If this financing approach has not worked in Canada, why do you think the government thinks that it will work overseas?

HMK: We have an ignominious history in Canada of public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the last few decades. For example, governments in Canada have created PPPs to expand public transit and other things that we used to deliver publicly. It has been largely unsuccessful. Infrastructure has not been built or has not been built well, which ends up saddling the public with a host of problems.

The best argument for PPPs and other blended finance approaches is that they minimize the short-term costs to the public. A government can say, “We are investing in a $1-billion project, but it only shows up on our balance sheet on the public budget as $100-million over five years.” So, it looks good because you are offloading those costs to the private sector. But in the long term, you end up paying for it anyway. You still have to pay for the project, and then someone has to pay for the profit the private partner is expecting to make. Either the public pays through user fees, or the state pays through these supposed innovative financing mechanisms that ensure that the private partner is not taking on any risk. It is a failed approach, but you can see the political appeal.

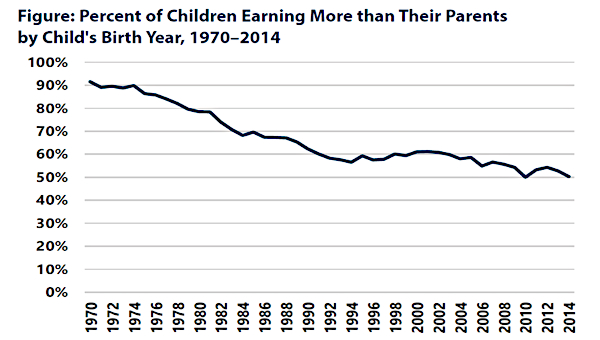

It is also important to note the broader context. Why can’t the public just accept the upfront cost of what should be, frankly, necessary public investment? That is the product of decades of shifting financial capacity from the public to the private sector. We have a private sector that is richer than ever and a public sector with less capacity than ever in many respects, at many levels. And so, we are in a position where governments must beg the private sector for capital because they do not have it anymore. So, we are in a difficult position where it is necessary to get private capital to build infrastructure at scale, but we are going about it in a way that is not addressing the root problem. Yes, we do need to come up with billions of dollars – trillions in the global context – to decarbonize and deliver the kind of development aid and financing that we need. But instead of saying we are going to take some of that value for the public and then spend it, we are just asking the private sector to deliver those public goods, and as noted, ultimately, that is an approach that is not going to work.

SJS and KS: So, what do you think the Canadian government should do instead?

HMK: I think an important part in the context of the green transition is two-fold. First, we need to make major investments across the economy that may not be profit-making in the short term. For example, we need to invest in research and development. We should be doing that through providing public funding to science and educational institutions. We also need to build things like electricity grids. As it stands, we are trusting ‘the market’ to build renewable power such as solar and wind, but you must plug it in somewhere. If the public is not building out a grid, then it is not going to be very useful to have all this new infrastructure. In short, we need to build public capacity to enable the transition. The public must lead so that the private sector can follow when it comes to energy and other issues.

Second, although renewable energy is becoming more cost competitive, ultimately, the reason we are trying to transition away from fossil fuels is an environmental one, a climate one. So just hoping that ‘the market’ will choose renewable energy for economic reasons is short-sighted. We need to recognize that the priority here is to reduce emissions, even where it is not profitable. We still need to invest and make regulatory decisions to reduce our emissions. Taking a pro-public approach where finance spending is primarily delivered (or at least guided by) the public allows us to balance these different considerations, not only economic but environmental and geographic.

A big part of the government’s current approach to the clean economy is investment tax credits saying, “Please spend money on clean energy, please spend money on clean manufacturing, we will pay you back for it.” Even if that works from a climate perspective, there is no guarantee those investments are going to go where we need them most. We want to target investments in communities that are at risk, communities that currently depend on coal, oil, gas, and in rural and remote communities that depend on diesel power, for example. We want to target money in these communities to support them and make sure there are viable jobs in those communities. But if you just throw this broad-based investment tax credit on the table, what is going to happen is all that money goes to corporate headquarters in Calgary and Toronto. And maybe it reduces emissions, maybe it increases investment in the clean economy, but it does not help the communities that need it. So again, that is just an example, but it is a good example of why we need to think bigger picture concerning spending. It is not just about the total amount of money we can raise. It is about where it comes from and whether we are using it in a pro-social way.

And then finally, building gender equity and equity considerations in general, how do we bring more racialized workers into the fold? How do we make sure, that we are not leaving immigrants behind or not prioritizing indigenous workers in those communities? It is more possible to achieve those goals in the context of public projects, where again, we can balance competing priorities. We can say, maybe we are going to make less money building this facility in a rural Albertan community, but doing so will help the First Nations that live there. We can make sure we are providing training opportunities for women in the community, et cetera, in a way that is just very hard to do with private projects. So, making sure the public can lead can help us address and balance all these competing priorities rather than trusting it to the market, which is always going to be guided first entirely by profit.

SJS and KS: Is there an example that you could offer in terms of a project that has worked, a public project like an energy project that addresses these equity concerns?

HMK: Well, I think that some of the best examples are from First Nations communities. After provincial utilities, First Nations are the largest owners of renewable energy infrastructure in Canada. Some funding is coming from the federal government, some from the private sector. These projects are win-wins. Rural communities that establish energy infrastructure foster economic development and generate employment opportunities within such areas. This also reduces communities’ reliance on major corporations and colonial utilities. Developing community-owned projects that serve the public interest ensures that the advantages of electricity production remain within the community. There are some great examples of this happening, but we need to enable that. Telling Bay Street to go build energy infrastructure for First Nations communities is a very different equation than saying, “How do we support these communities building their own energy infrastructure in a way that they own it and benefit from it over the long-term?”

SJS: What is the Canada Infrastructure Bank doing and what should it be doing instead?

HMK: The Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) still focuses too much on partnering with the private sector, but it is getting better over time. One example is buying electric buses. For a long time, the CIB was trying to encourage the private sector to do this, but it did not work. So instead, the CIB has started acting like a green public bank that provides low-cost loans and other kinds of preferential financing to public institutions. Instead of trying to incentivize the private sector, you say, “You are a municipality, a province, a non-profit; we are going to provide you money at better than market rates so that you can do good things for your communities.” And that is a great use of public financing. And at the end of the day, maybe the community owns it, maybe the government has a stake in it, whatever, but the public ultimately still owns it. And that is an important part of this. We should not give money to the private sector so that they can own stuff and extract value from it, but make sure that at the end of the day, the public owns public infrastructure.

SJS and KS: Is there anything else you would like to add?

HMK: When it comes to not only the clean economy but any kind of public infrastructure, goods and services that are meant to serve the public; our priority should be that they are owned and controlled by the public as well. There are different ways to do that, but to the extent that we are leaning increasingly on the private sector, on private investors to deliver public goods, we are ceding control of those goods to institutions, to organizations that do not care about the public. That is not their mandate. And that is something we must be very careful about. The solution lies not just in coming up with the biggest dollar figure, which is what a lot of governments want to do by partnering with the private sector. It is about doing quality work that is in the public interest even if it comes at a higher upfront cost. •

Additional resources:

- Kathen, N., & Mertins-Kirkwood, H. (2022, October 22). Bet big: A citizen’s guide to green industrial policy in Canada. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

- Marois, T. (2022, October). A public bank for the public interest: Recommendations for the Canada Infrastructure Bank five-year review. Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE).