Das Kapital – A Cold Case

Das Kapital is one of those crime novels where readers know early on who the villain is. Whether or not he is caught remains an open question until the end. So far, he has not been caught. This is why further episodes have been written since Marx’s death.

The story begins in a ghostly world. It seems peaceful and free. It is inhabited by people who trade goods with each other. Everyone gives what they have but don’t need, and everyone takes what they need but don’t have. A wide variety of things are exchanged, but they have only one thing in common: they all have the same value. That’s why no one can make themselves rich at the expense of their respective trading partners: no one buys cheap, and sells dear.

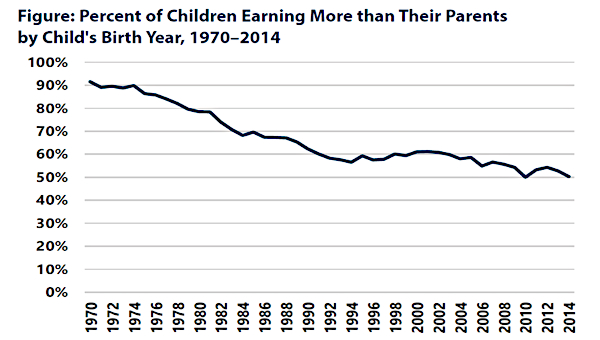

Nevertheless, and that’s the spooky thing about this world of exchange: a few are getting richer and richer while everyone else is struggling not to get poorer. Discontent is growing amongst those who are struggling. How can some people accumulate so much wealth in a world where everyone is equal and are exchanging things of equal value? They are outraged but cannot explain the increasing inequality. Finally, they hire a detective. Karl Marx promises to get to the bottom of the matter. After years of research, he presents his final report, in 1867, and writes the name of the culprit on the title page: Capital, an organization that promotes the enrichment of a minority in the name of free exchange among equals. Crime scene: factory. Victims: wage workers and the environment.

Episode I: The Criminal Will Judge Himself

To the surprise of his clients, Marx claims that the organisation in question is in no way a criminal organisation. It operates in public; its leadership does not violate any law, but has cast the moral principles of freedom and equality as the legal forms of private property and freedom of contract. However, only people who have private ownership of the means of production, i.e., machines and materials, have access to the leadership of what Marx calls the capitalist organisation of production. His clients are also members of the organisation, but they are unlucky in that their labour is the only thing they have to offer in exchange for food. In contrast, the capitalist leadership of the organisation is fortunate in that the use of this labour in the factory creates more value than it costs to purchase. This surplus value is realised on the market by selling the goods produced in the factory and kept by the capitalists because the means of production and the labour used in production are their property.

This exploitation of workers by capitalists is therefore legal and moreover, necessary, because only the appropriation and reinvestment of this surplus value allows capitalists to survive in the competition they engage in amongst themselves. They are not necessarily morally corrupt subjects eager to exploit their workers. They simply do not want to be pushed out of the market and leadership positions.

If workers wanted to escape this exploitation, they would first have to become lawbreakers, then appropriate the means of production from the capitalists and operate them on their own. The prospects for this were looking pretty good. As a result of competition amongst themselves, some individual capitalists are driven into bankruptcy, while those that remain grow bigger but are plagued by crises. If they produce a lot in order to steal market share from competitors, wages rise along with the demand for the extra labour they need, profits get squeezed. If in response, the capitalists reduce production to lower wages again, through higher unemployment, they create a lack of mass purchasing power to sell the goods, i.e. lack of demand, that was previously produced in large numbers. An overproduction crisis ensues.

When capitalists try to escape this cycle of profit squeeze and lack of demand by introducing labour-saving technologies, they saw off the surplus-value-creating branch of living labour. So, as a result of capital concentration and crises, capitalists become an endangered species while the ranks of the proletariat, which have grown with capital accumulation, provide the necessary mass base for a socialist revolution.

In order to mobilize this base to carry out the historic judgment on the capitalists, Marx’s followers founded unions, parties, and workers’ educational associations. However, the revolutionary momentum waned when a sustained economic upswing began in the mid-1890s. This was not foreseen in Capital. With the upswing, the wages of many workers rose, and although the number of capitalists fell, their solidarity amongst themselves increased. A new idea, that party and union leaders could agree on social reforms with corporate leaders and governments without destroying the capitalist organization, gained more and more supporters.

Marx died in 1883. So, a new generation of detectives have begun asking themselves how, despite his predictions, a sustained boom could have occurred. They started going through Das Kapital again. Did Marx miss something? Or had capitalism changed so much that his analysis needed to be adapted to the new times? They were searching for the causes of the boom, but also for breaking points. One trail lead to the boardrooms of corporations, cartels and conglomerates. Another lead to the world market.

Episode II: The Rule and the Exceptions

The result of the investigation by the young generation of detectives: A new wave of colonization had allowed large companies to invest overseas, particularly in shipping and railways. This is what triggered the general boom. Given the natural limits of spatial expansion, however, political conflicts were bound to arise amongst the colonial powers. And so they did. And a revolutionary wave rose from the trenches. However, it led only to victory in Russia, where there were more peasants than workers in uniform.

The workers’ movements in the West were defeated by organized counter-revolution, while peasant movements led the anti-colonial revolution to victory in many countries. Members of the Marx Detective Agency concluded that this victory would constrict the world market, lead to sales crises, and finally, to the workers’ revolution predicted by Marx. But when the crisis came in the 1930s, only the Soviet Union had dropped out of the capitalist world market. In the period after the Second World War, when the number of non-capitalist countries increased, there was an upswing that far exceeded the one at the end of the 19th century. While the detective agency was still pondering how much neo-colonialism had contributed to the new upswing, unexpected workers’ revolts broke out.

The reason: the economic upturn was accompanied by a speeding up of work and inflation that was eating up real wages. This time, in addition to the male workers, women also revolted. Drawn into the labour market by the economic upturn, they were expected to work double shifts: in the home and in the company. And the youth revolted, seeing little future for themselves in work dictated by others and in a natural environment suffocating under the rubbish of prosperity. It was not the crisis but rather the economic upturn that led to the uprising. But before the various centers of rebellion could unite to form a common front against the capitalist organization, the capitalists began to turn the world upside down. In the process, their left-wing opponents lost their footing.

Episode III: A Tough Dog

The expansion and restructuring of the capitalist organization into an opaque network of commodity and capital flows that had taken place since the early 1980s could, at best, be found between the lines in Marx’s work. It was almost non-existent in his successors’ work. Until the revolts of the 1970s, most of them assumed that the great crisis was still to come. That the peasant revolutions in the south were only a detour to the workers’ general reckoning with the beast. But then they had to accept that the revolts that had begun during the boom did not escalate into revolution during the crisis.

In contrast, the capitalists learned to use the crisis as a weapon in the class struggle. A series of financial and fiscal crises served as a lever to cut back social services and security and to privatize public companies. Automation, the dismantling of hierarchical production processes and relocations have deprived the old organizational centers of the working class of their foundations and thus rendered the class almost incapable of action. The money and capital fetish, which Marx had only hinted at, turned into a mass religion as the production and distribution networks, controlled by financial centers of the world, became less transparent.

Preview of Further Episodes

Marx and the detectives were wrong. So far, it’s not that a bunch of capitalists exhausted by competition and crises have had to hand over the organization of the social life to the hardened-by-class-struggle proletarians of all countries for the purpose of collective self-management. Rather, the capitalists have transformed every challenge posed by the labour movement, and other social movements, into new production processes and markets, under their own control. In doing so, they have created a world that looks very similar to the one Marx describes in Capital. But it is one that also bears the scars of the struggles that have been waged against capital, a world that today lacks a systemic challenge that could promote the exit from self-destructive crises. We live in a capitalist world that is so unloved that the absence of such a challenge is surprising.

A new generation of detectives will write further episodes of Capital, and find new clues to overcome it. Maybe. We are working on it. •