Assad’s Fall, Turkey’s Victory? A Critical Appraisal

On 8th of December, Bashar Al Assad’s regime in Syria collapsed, and it is reported that he fled to Moscow. What could not be achieved in almost 14 years was accomplished in just 12 days, through an unexpected offensive primarily led by the Salafi radical Islamist group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), though other opposition groups supported the offensive, such as the Syrian National Army (SNA), directly backed by Turkey.

There is now a tendency to view this outcome as the victory of Erdoğan’s Turkey, which has supported the Islamist Syrian opposition against the Assad regime since the early days of the civil war. This outcome seemed highly unlikely until very recently, as the events around the civil war and the regional political economy dynamics from mid-2010s had amounted to an almost frozen conflict, and Turkey’s ambitions for a regime change had largely come to an end.

A series of recent regional and international developments, alongside Syria’s domestic conditions in the past few years, seem to have played a decisive role in this outcome, benefitting Turkey and Turkish-backed opposition, as well as some other powers such as Israel.

Turkey’s Regional Strategy Post-Arab Spring

Turkey’s approach to the Syrian civil war must be understood within the context of its broader approach to the region following the Arab uprisings, which began in Tunisia in December 2010 with demands for “bread, freedom, and social justice.” Amidst the region’s upheaval, Turkey, under Erdoğan’s AKP, sought to position itself as a pivotal actor. The AKP presented itself as a supporter of democratization in the region, leveraging its image as a model that successfully blended moderate Islam, economic prosperity, and democracy, in opposition to authoritarian regimes. Visits by Erdoğan to Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya in 2011 aimed to reinforce this narrative.

From a critical perspective, however, it is important to highlight Turkey’s role in international efforts, which aimed to make sure that the transition in the region would not amount to a rupture from the neoliberal integration into the world market. The illustration of this was the “Deauville Partnership with Arab Countries in Transition” established at the G8 Summit in France (May 2011), consisting of the G8 plus Turkey, Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, and various international financial institutions (IFIs) offering various loans to these countries in exchange for implementation of further neoliberal reforms. Politically, Turkey’s engagement increasingly amounted to a full support of Muslim Brotherhood in these countries and in the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, as it was thought that Turkey would be able to influence like-minded regimes and expand its economic and political interests much more easily.

This was not always in line with the domestic political dynamics of the countries in question, however, as it was observed with Sisi’s brutal military coup in Egypt against the Muslim Brotherhood and its president Morsi in 2013. Turkey’s staunch opposition to Sisi’s regime led to a collapse in bilateral relations and later regional isolation, as the Sisi regime was backed by powerful regional and international actors. Similarly, in Tunisia, the Islamist Ennahda party was contained by secular forces, limiting Turkey’s influence.

The Syrian Quagmire: From Regime Change to ‘Normalization’

Syria became the cornerstone of Turkey’s post-Arab Spring foreign policy and a flashpoint for its geopolitical ambitions. Initially calling for reforms, Turkey quickly shifted to aggressive support for regime change, aligning with Islamist opposition forces, which included extremist groups. However, this policy became increasingly untenable as the Assad regime proved to be resilient, bolstered by support from Russia, Iran, Hezbollah, and to an extent, China.

Turkey continued to support the Syrian Islamist opposition, but rather than focusing on regime change, with the new domestic and regional dynamics from mid-2010s, it started to focus more on its immediate ‘security concerns’ and the question of Kurdish autonomy in Northeast Syria, represented by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

Domestically, the nationalist alliance of the AKP, which came to the fore in November 2015 elections, and the July 2016 Gülenist coup attempt created a ‘securitized’, ultra-nationalist, and an anti-US political atmosphere. The failed coup deepened Turkey’s mistrust of the United States, which was perceived to have supported the coup plotters. In August 2016, the Turkish army started operation Euphrates Shield in Northern Syria, mainly against the SDF, but targeted the ISIS as well. As the Kurds in Syria were supported by the US (especially in the struggle against ISIS), this soured the AKP’s relations with the US further.

Regionally, Russia’s direct military involvement in the Syrian civil war to protect the Assad regime from 2015 onwards was a factor that the AKP could not ignore, and it started to work with Putin more closely, leading to initiatives such as the Astana process regarding Syria and Turkey’s purchase of the S-400 defence system from Russia despite being a NATO member. Two further significant operations were conducted focusing on the Kurdish controlled regions in Northeast Syria, i.e., the operation Olive Branch (2018) and the Peace Spring (2019), achieved by gaining Russia’s consent and facilitated by the then US president Trump’s stance (withdrawing support from the SDF).

The stance of other powerful regional actors, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE and Egypt against the Muslim Brotherhood and regime change, was another important factor that severed Turkey’s relations with these countries until the early 2020s, leaving Qatar its only partner in the region. However, the way Turkey engaged with the region in the last decade or so was exhausted, particularly within the context of its crisis-ridden domestic political economy trajectory in recent years. This led to a search for a ‘new era’ with the regional foes in the early 2020s. As such, diplomatic visits took place with the UAE and Saudi Arabia in 2022, and currency swap deals and investment pledges were made.

In return, Turkey’s support for regime change and its explicit pro-Muslim Brotherhood stance largely came to an end. Diplomatic relations commenced again with Sisi’s Egypt, too, which Erdoğan had previously called illegitimate for a decade, and similar developments were taking place with the Assad regime in Syria, with Erdoğan’s attempts to start a dialogue with Assad.

Unravelling Assad’s Fall and Its Implications

Perhaps relying on these regional developments in its favour and his allies, and hence confident that regime change was not on the table, Assad’s stance was inflexible and he did not want to engage with Turkey while Turkish forces were on Syrian soil. Following this, it seems that Turkey gave the green light to the Syrian opposition for the offensive led by HTS, though it is questionable that these parties expected the fall of the regime, at least in the short term.

While there are signs that Russia and Iran were aware of the plan prior to the offensive, they were both not in a strong position to support the Syrian Arab Army (with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s brutal war in Gaza and Lebanon weakening these countries’ military capacities and focus) and remained reluctant with the rapid advancement of the opposition. Perhaps Syria’s normalization process with the Gulf and the fact that the UAE was discussing lifting Assad sanctions with the US in exchange for break with Iran contributed to Iran’s half-hearted stance.

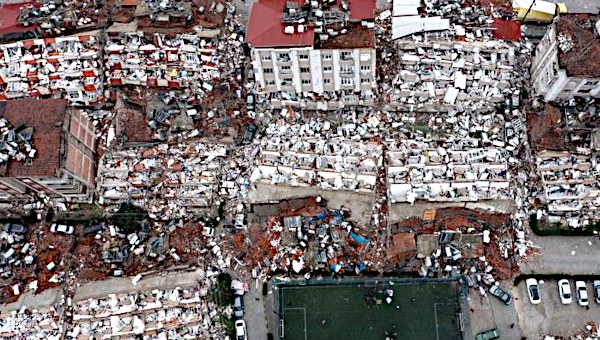

The regime army turned out to be very weak and exhausted and quickly accepted the situation on the ground. It is important to note that after years of conflict, widespread poverty and misery, economic collapse, and corruption, there has been growing discontent against the regime in regions it controlled despite repression, and there was no popular support for Assad. Under these conditions, the regime disintegrated quickly.

It would also be naïve to think that the US, NATO, and Israel did not have any knowledge or involvement in this process. Despite ongoing tensions, it was reported that Israeli domestic intelligence agency (Shin Bet) chief Ronen Bar visited Ankara on 19 November. On 25 November (two days before the offensive), NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte was in Ankara. These were also highlighted by Alastair Crooke, a former British diplomat and MI6 intelligence officer.

Israel has started to occupy Syrian territory further and launched attacks following the regime’s fall on Sunday, as one of its most important historic adversaries in the region eliminated, with significant implications for the question of Palestine and suffering thereof. Major Western states are content with this outcome as well. The result has been humiliation for Russia, and further loss of power for Iran in the region. These raise some questions about the perennial issue of Turkey’s ‘shift of axis’ in recent years.

Despite all the tensions – chief among them the Kurdish question, which will continue to be a central issue in the new era for Turkey – rhetoric, occasional independent actions and flirtation with non-Western powers, Turkey remains as a firm NATO member, ultimately furthering the Western interests in global capitalism. The condition of the MENA region since the initial hope created by the uprisings 14 years ago turned into despair for more than a decade, entrenching different forms of authoritarianism, inequalities, and conflict-ridden conditions, to the detriment of the labouring classes and oppressed masses.

Alongside other reactionary forces, Turkey’s engagement with the region since the uprisings played an important role in this outcome. While a new era starts for the Syrian people, realities on the ground makes it very difficult to be optimistic. Regional and global imperialist powers are now looking to protect their interests by integrating themselves with the new rulers. The new regime is signalling its intention to restructure the economy with free market reforms, further enticing these powers and their capitalists. All that remains to hope for is that these forces face new forms of popular resistance for ‘bread, freedom, and social justice’. •