A Prime Competitor: Understanding Amazon’s Market Power

A large body of scholarship has emerged in recent years attempting to assess if Amazon is a monopoly. Such accounts generally define monopoly in terms of the neoclassical “quantity theory of competition,” which measures competition by the number of sellers in a market.1 According to this framework, “perfect competition” gives way to increasingly “imperfect competition” over time as the number of firms in a particular sector declines through concentration and centralization. As the market comes to be dominated by a smaller number of giant firms, it becomes impossible for new challengers to compete – what economists call “barriers to entry.” Since the monopoly firms are largely free from competition, they can effectively fix prices and thus rake in monopoly “super profits.” Consequently, they have little incentive to invest in new technologies, improve efficiency, or intensify the exploitation of labour.

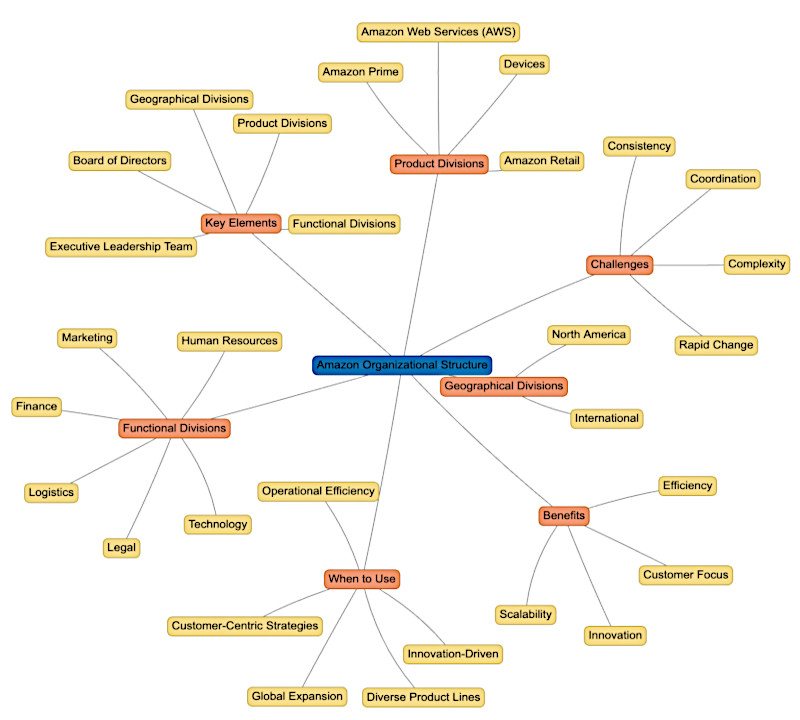

An apparent paradox therefore emerges in characterizing Amazon. Its “bigness” and lack of a direct competitor would seem to suggest that it should be considered a monopoly. And yet, far from exhibiting the tell-tale signs of increasing monopoly prices, inefficiency, and technological stagnation, Amazon has engaged in cutthroat price competition, built a highly efficient and technologically advanced logistics system, and unleashed competitive forces whose effects have reverberated across the retail sector and beyond. Moreover, Amazon’s distinct vertically integrated structure, competing across a range of sectors including retail, e-commerce, logistics, online search engines, and media entertainment – each dominated by large firms – suggests that today’s giant corporations are not significantly encumbered by barriers to entry. All this indicates that the understanding of “monopoly” within mainstream economics (as well as significant sections of the left) has popularly obscured the intensely competitive nature of modern corporate capitalism.

As we’ll argue, Amazon’s dominance is not rooted in a static “monopoly” position, but rather emerges from a competitive “war among firms.”2 As such, it must continuously fight to sustain and renew its power through unceasing innovation and restructuring. In addition to offering very low prices, the efficiency of its advanced logistics, warehousing, and transport system allows Amazon to profit from circulating the commodity-capital of a large number of “independent” capitals – increasingly, that of other large firms. These capitals also benefit, as selling on Amazon enables them to increase profits and reduce costs, even despite the fees it charges. To make sense of this, we draw on the “real competition” school of Marxian economics, which holds that competition is not merely an effect of the number of sellers in a particular market, but occurs as all firms seek to maximize their share of the total social surplus. From this perspective, competition is not reduced but intensified as units of capital get larger.

Circulation, Competition, and Market Power

The case of Amazon makes it especially clear that neoclassical economic theory fails to capture the competitive dynamics of contemporary corporate capitalism. As Marx demonstrated, competition is not a matter of the number of sellers in a particular sector. Capital is not intrinsically connected to the production of any specific use-value (i.e. concrete good or service) but is oriented around maximizing monetary accumulation. Capitalists will invest in producing whatever commodities are able to facilitate the realization of surplus-value in the money-form through sale on the market. As such, particularly for large corporations that can marshal huge financial power, barriers to entry are ephemeral and temporary. Indeed, “as capital requirements increase throughout the economy, this simply means that the necessary armaments for waging a successful competitive battle are also increasing.”3

As Marx emphasized, competition takes place both among producers of identical use-values (intra-sectoral), as well as firms in different economic sectors (inter-sectoral). That is, competition occurs not just within individual product markets, but across the entire economy as capital flows into investments with higher returns and away from those with lower returns in search of maximum profits. The primary choice every capitalist faces is thus where to invest. As the circulation of capital across space and among the different branches of production becomes easier, quicker, and cheaper – what economists call increased “capital mobility” – competitive pressures are intensified across all sectors and assets to either maximize returns or face the withdrawal of investment. Since the large corporation is the most mobile, it is the most competitive form of capitalist organization.

Corporate capitalism, therefore, has become more, not less, competitive over time. Larger firms are more easily able to restructure by moving into profitable markets while divesting from others. Moreover, such firms are capable of competitively allocating capital across operations, and even individual facilities, with minimal transaction costs. In this way, competition also occurs within large firms. They also possess the most substantial research and administrative capacities for assessing the value of different operations and investment opportunities. These competitive disciplines have propelled the process of “financialization,” whereby the role of money-capital, as the most abstract and most mobile form of capital, has been enhanced.4 Since money can be invested in producing any commodity, firms organized around the allocation of money-capital cannot simply be identified with particular economic sectors, but are able to invest in whatever economic activities are most profitable.

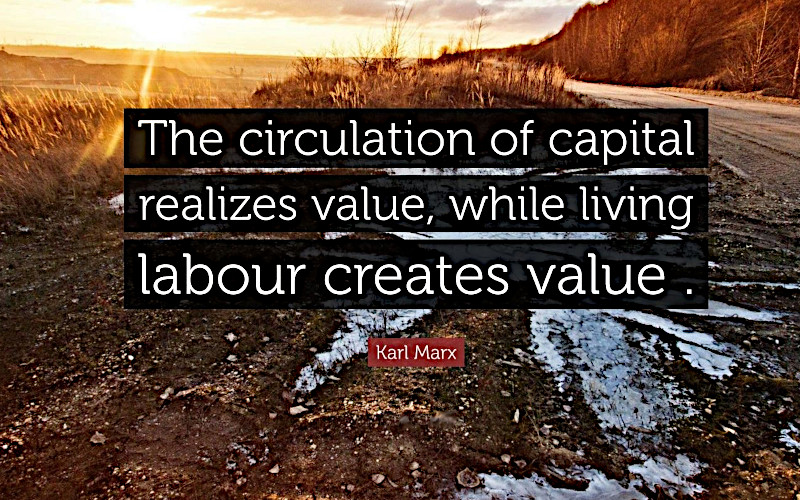

Competition also disciplines capital to accelerate turnover time, or the amount of time it takes capital to complete the circuit from investment to sale, summarized by Marx in the formula M-C-M’. The faster capital is turned over, the more surplus value is produced within a given period of time. To understand this, it is necessary to break down the M-C-M’ process further. After being advanced in the money-form (M), capital is transformed into the commodities labour-power and means of production (C). This allows capital to take on its productive-form (P), entering a process through which a new commodity is produced (C’). Marx calls this new commodity “commodity capital,” as it is pregnant with surplus value waiting to be realized in the money-form through a sale (M’). Marx expressed this in the extended formula M-C…P…C’-M’. The circuit of capital is thus a unity of production and circulation: while M-C and C’-M’ take place within circulation, P…C’ occurs within production. Turnover time, then, consists of production time plus circulation time.

Circulation time comprises both selling time and buying time. Selling time denotes the time required to convert commodity-capital into money, thereby realizing surplus value. It encompasses the entire period during which capital takes the form of the commodity – from the conclusion of the production process to the sale of the product. Buying time, on the other hand, refers to the period during which this money awaits conversion back into the commodities labour power and means of production. This encompasses the entire time in which capital remains in the money-form prior to re-entering production. Just as “the capital as C’ is anxious to assume the money form,” so “the capital as M’ is anxious to get rid of it” because “as long as it exists in the shape of money… the capital remains idle.”5 Capital is thus driven to compress circulation time, as a component of overall turnover time, as much as possible.

Just as capital’s competitive drive to minimize production time demands the implementation of new technologies, that same drive also compels firms to reduce circulation time through the improvement of transportation, logistics, and communications infrastructures. The transformation of capital into “the different forms which [it] clothes itself in its different stages, alternately assuming them and casting them aside” involves an abstract movement. However, as the circulation of capital is the “movement of abstraction in action,” it also depends on the physical movement of goods and money. While commodities may “remain in the same warehouse while they undergo dozens of circulation processes, and are bought and sold by speculators,” circulation ultimately requires “a motion of the products in space, their real movement from one location to another.”6 Reducing circulation time, therefore, necessitates continuously developing the physical conditions of circulation.

Capital is not a thing, but rather “value in motion.”7 Yet the continuity of the circulation process is complicated by the fact that it is carried out by individual capitals, which are linked together into value chains even as they compete with one another to maximize their share of surplus value. Each form that capital adopts as it moves through the circulation process roughly corresponds to a particular economic sector or “branch of business.” Money-capital therefore becomes the specialized function of the financial sector, productive-capital that of the industrial sector, and commodity-capital that of the merchant or retail sector. These different activities are performed by competing (and often diversified) firms, which become “modes of existence of the various functional forms” capital “constantly assumes and discards” that have been “rendered independent by the social division of labour.”8

Accordingly, industrial capital undertakes the production of surplus value, while merchant capital and financial capital profitably circulate commodities and money. However, Marx argued that “storage and transport of goods in a distributable form” can also be productive of surplus value. The continuity of the production process requires that inputs and outputs be transported across space between the individual capitals fulfilling particular stages of the process, making transportation of the unfinished commodity itself a stage in the production process. Similarly, the ultimate consumption of a finished good requires that it be transported to the place where consumption occurs. Those activities necessary to affect such a “change of place” must therefore be seen as “production processes that continue within the process of circulation.” Consequently, as an agent of the circulation of industrial capital, merchant capital is, in practice, also involved in producing surplus value, as Marx recognized.9

The circulation of capital takes place through the unplanned and competitive interaction between individual capitals. These are linked into value chains, meaning that the inputs purchased by one capital are the outputs sold by another. The turnover of individual capitals is dependent on the production of inputs, and purchase of outputs, by other individual capitals. Obstructions can lead to crises. If the transition of commodity-capital into money-capital is impossible, for example, surplus value cannot be realized and commodities pile up, potentially leading to a crisis of overproduction. Similarly, if the commodity inputs necessary to begin production are not available, or not available in the right quantities, a crisis of disproportionality can emerge. While markets may be able to adjust to resolve local disruptions, if the problem becomes generalized a crisis of overproduction could result.

That the circulation of capital takes place across competing individual firms also creates opportunities for the exercise of power. In addition to warding off competition from producers of the same or similar products, firms also compete to maximize their share of surplus value within value chains. By leveraging control over strategic points within the general circulation of capital, firms may increase their bargaining power relative to suppliers and customers – seeking to prevent value from “leaking” to others in the supply chain by minimizing the prices paid for inputs and maximizing those charged for outputs. This competitive struggle shapes the division of surplus value both within and across sectors. Thus, even the most concentrated sectors are not static, but highly dynamic, with the distribution of surplus shifting as the balance of power between firms is shaped and reshaped by changing economic, organizational, regulatory, and technological conditions.

Crucially, competition does not only drive firms to seek higher prices for their output but also to develop new technologies and labour processes that reduce costs. This includes not only increased productivity within the sphere of production, but innovations in circulation processes as well. To maximize profit, merchant capitals are compelled to reduce circulation costs and turnover time, which in turn accelerates the compression of space and time for all capitals reliant on these infrastructures.10 Consequently, merchant capital plays a pivotal role in the general circulation of capital and in the competitive struggle among all firms. The valorization of each capital within a value chain hinges on the realization of surplus value once the commodity enters the realm of consumption. Thus, control of commodity capital confers influence over the realization of surplus value for all capitals in a value chain.

While from the perspective of the individual productive capitalist, the product is transformed into money as soon as it is acquired by the merchant, all that has happened from the point of view of the product “is a change in the person of its owner.” Indeed, “it is still commodity capital as before, a saleable commodity; but now it is in the hands of the merchant instead of the producer.”11 For this reason, Marx argues that commodity capital should not only be viewed as “a form of motion common to all individual industrial capitals, but at the same time as the form of motion of the sum of individual capitals” linked into value chains – that is, “of the total social capital of the capitalist class.” From this perspective, “the movement of any individual capital simply appears as a partial one, intertwined with the others and conditioned by them.”12 Only when the commodity is finally consumed does it cease to be capital, which then sheds its commodity form and returns to the capitalist in the form of money.

Possession of commodity capital can thus confer significant leverage in the competitive struggle among all capitals for surplus value. Merchant capitals may acquire control over commodity capital as a result of their ownership of infrastructures and distribution systems which offer unique access to markets, or which facilitate the especially rapid transportation of products “from one separate place of production to another” and from “the sphere of production to the sphere of consumption.”13 Merchant capitals that develop superior transportation and distribution systems can offer productive capitals the opportunity to reduce circulation time and increase profit rates. Thus while control over commodity-capital confers power on merchant capital within the circulation process, this does not necessarily entail raising prices: in fact, prices could decrease in tandem with reduced turnover time and circulation costs.14

The struggle among all firms for strategic advantage, then, is not about negating competition, but occurs on the basis of a continuous “war among firms.” Firms in the same sector seek to produce similar products more efficiently and cheaply, while firms across all sectors compete for investment, and try to leverage their control over strategic points within the circulation process to increase their bargaining power vis-à-vis customers and suppliers. Merchant capital occupies a particularly strategic position within this process. Yet merchant firms must both attract productive capitals to sell their output as quickly as possible to the largest markets, and consumers to purchase it at competitive prices. They are thus competitively disciplined to continuously revolutionize the means of circulation, developing new infrastructures and technologies to reduce transaction costs and turnover time for all capitals.

Amazon’s Competitive Dominance

Amazon is a merchant capitalist firm, embodying the circuit of commodity capital in organizing the circulation of commodities pregnant with surplus value. It acquires products from manufacturers or other retailers, stores them in warehouses, manages this inventory, sells to consumers, and transports commodities from the sphere of production to the sphere of consumption. Thus, in addition to the “pure” merchant capitalist practice of “buying cheap and selling dear,” Amazon has invested a staggering amount of capital to construct a vast circulatory system for transporting, dispersing, and storing commodities – all productive activities. Like all merchant capital, Amazon is compelled by the “coercive laws of competition” to continuously reduce circulation time and circulation costs, thereby accelerating turnover and enhancing circulating efficiency for all capitals utilizing its infrastructure.

Large warehouses known as Fulfillment Centers (FCs) are responsible for receiving incoming shipments from suppliers and sellers, storing products, picking items from shelves to fulfill orders, packing goods into boxes, and preparing them for shipment. Sortation Centers (SCs) focus on sorting and organizing packages of commodities received from FCs, which have already been purchased by customers, and sending them out for delivery. The competitive drive to compress circulation time, slash circulation costs, and maximize profits compels Amazon to maximize the efficiency of these facilities through work discipline and productivity improvement. This drive toward “time-space compression” has also been reflected in the expansion of Same-Day Delivery Centers, where particularly in-demand commodities are stored for delivery to customers’ homes the very same day the order is placed.15

In addition, Amazon operates a cloud-computing business, Amazon Web Services (AWS). Cloud computing allows firms to purchase computing capacity on demand, without needing to invest in permanent IT infrastructures. AWS is therefore an extension of Amazon’s merchant capital activities, leasing out means of production to other capitalists. Centralizing computer capacity in this way creates economies of scale, enabling other firms to reduce their own costs. Amazon continues to make substantial investments in expanding this capacity, which entails low marginal costs while yielding high margins. Consequently, although it represents a relatively small portion of Amazon’s revenue, AWS is responsible for a very large portion of its profits (68%), thus strongly appealing to investors. AWS has now become a major business in its own right, serving as the “back-end” for a significant portion of internet traffic and generating a steady stream of income which supports all the firm’s operations.

Amazon is dominant within the cloud sector, although it faces increasing competition: AWS maintains a 30% market share, Microsoft and Google have captured 25% and 11% shares, respectively. Some view the cloud sector as the paradigmatic example of a monopolistic “rentier” market, and in more extreme accounts, even as the leading edge of a new “techno-feudal” mode of production supposedly distinct from capitalism.16 However, what we observe is not the stagnation of uncompetitive monopoly (let alone feudalism), but the characteristic dynamics of capitalist competition. Such competition has propelled technological development, cost-cutting, and capacity expansion. It has also reinforced the integration of AWS and Amazon’s other operations, as it has encouraged clients to use additional logistics and supply-chain management services tailored to their operations. This, in turn, has reinforced Amazon’s need to continue investing in its cutting-edge logistics capacities.

Indeed, although AWS has become an important business in its own right, its competitiveness cannot be understood in isolation from its interconnection with Amazon’s core logistics, retail, and retail operations, which comprise nearly 85% of Amazon’s net sales. If Amazon’s logistics support the competitiveness of AWS, so does AWS support the competitiveness of its logistics. As we have seen, merchant capital is competitively disciplined to accelerate circulation velocity and reduce circulation costs by developing communications and transportation technologies and infrastructures. AWS emerged through this very process and remains important for Amazon’s efficient circulation of commodity capital. The computing power and data analytics it offers enhance inventory and route management as well as demand forecasting. Moreover, AWS connects Amazon’s logistics network to consumers, instantly responding to orders and minimizing the physical circulation of commodities.

Amazon’s competitiveness is rooted in its advanced logistics and lightning-fast delivery, which are sustained through the firm’s very high levels of investment in these infrastructures. While all merchant capitals are compelled to maximize circulation velocity and efficiency, Amazon faces specific pressures in this regard. Unlike brick-and-mortar retailers, which provide the opportunity to acquire commodities on the spot but require the customer to travel to a physical location, Amazon organizes the circulation of commodities directly to the customer’s door – but requires that the customer wait for delivery. Competitive success, therefore, means bringing delivery time to an absolute minimum. Amazon has been remarkably successful at this, however, as over 200 million people are now enrolled in Amazon Prime, which promises even shorter delivery times, and free shipping, for designated products the pressures for efficiency continue to be intense.17

Amazon’s drive to accelerate circulation velocity and rapidly deliver commodities to consumers is reflected in the spatial structure of its warehousing and logistics system, which operates across integrated national and regional scales with key commodities warehoused near major urban centers. This means that the flow of commodity-capital through Amazon’s logistics infrastructure is by no means “frictionless,” but spatially segmented at the regional level. In fact, 76% of orders are shipped from an FC within the customer’s region.18 Moreover, Amazon’s high levels of investment enable it to maintain substantial surplus capacity, which is underutilized except during certain peak times. This affords the system considerable flexibility in re-routing the flow of commodities to circumvent any interruptions or blockages.19 Nevertheless, the spatial fragmentation of commodity circulation across Amazon’s logistics network creates contradictions and potentialities for disruption, which well-organized workers may strategically exploit.

Despite this spatial decentralization, Amazon centralizes control over the flows of commodity-capital acquired from other productive and merchant capitals. These include first-party sellers (1P), who sell their inventory directly to Amazon, making it “the seller of record”; second-party sellers (2P), or retailers whose independently-owned inventory is integrated with and supplements Amazon’s own; and third-party sellers (3P), who use Amazon to sell to consumers, although their inventory is frequently managed by Amazon via third-party logistics (3PL) contracts in the form of a service called Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA). Smaller 3P sellers supply a large and growing proportion of the commodities Amazon circulates. At the same time, Amazon is now positioning itself to manage the inventories and supply chains of other large corporations by offering “Supply Chain by Amazon” services.

1P sellers primarily include mid-market brand owners, which lack the cache or brand value that could support their ability to sell independently. 3P sellers are smaller retailers or manufacturers. That “there is only one Amazon” leaves these firms little alternative but to rely on the logistics system it owns and operates. Moreover, because suppliers and sellers are fragmented, while Amazon is concentrated, the former actually compete with one another to supply Amazon on terms favorable to the latter. Competition among fragmented 1P suppliers and 3P sellers thus reinforces Amazon’s market power and strengthens its bargaining position vis-à-vis these firms – compelling 3P sellers to accept the fees it imposes and 1P sellers to sell inventory to Amazon on favorable terms. Nevertheless, suppliers and sellers benefit from selling through Amazon insofar as it speeds up turnover time, reduces circulation costs, and connects them with a wider market.

3P sellers constitute a distinct type of business that specializes in nothing other than selling on Amazon. That Amazon controls 80% of the US e-commerce marketplace market, and the superiority of its logistics and inventory management, means that these firms have little ability or incentive to diversify to other platforms. Amazon also blocks sellers from marketing products more cheaply elsewhere, effectively internalizing the fees charged by Amazon within product prices.20 While these anti-discounting practices are facing an antitrust challenge from the Federal Trade Commission, and this has not stopped other platforms from competing with Amazon in specific markets (electronics, home improvement, pet supplies), the vast majority of 3P sellers today see little alternative to selling through Amazon.21 Thus, in centralizing commodity capital, Amazon also centralizes these smaller productive and commercial capitals. Investments in these “independent” businesses are, in effect, investments in Amazon itself, as their products are exclusively marketed, handled, transported, and sold by Amazon.

Amazon’s market power has been reflected in its ability to negotiate favorable wholesale prices with 1P sellers, as well as to impose substantial fees on 3P sellers – which can exceed 50% of sales revenue. Amazon applies three kinds of fees: referral fees, fulfillment fees, and advertising fees. Referral fees are a percentage of each item sold, typically 15%, although this varies by product – with some (computers) as low as 8% and others (eyewear) as high as 17%. Fulfillment fees are charged for Amazon’s 3PL services, covering picking and packing, shipping and handling, customer service, and returns. Sellers are required to use Amazon’s 3PL services in order for products to be labeled “Prime,” making them more attractive to Prime members. As a result, 90% of Amazon’s top 10,000 sellers use FBA. Finally, advertising fees are charged for access to preferential screen space, including search rankings and “highly rated” product designations.

While referral fees have remained relatively static, Amazon has continuously hiked fulfillment fees and captured growing revenues from advertising fees. Since search results are by no means “organic” but are purchased by sellers, successfully selling products on Amazon effectively requires sellers to pay fees in order for their products to be visible in search results. Amazon has allocated greater space for paid results over time, such that today few of the first 20 search results are typically “organic” or based on “meritocratic sorting.” The intensification of competition among sellers for screen space has allowed Amazon to capture a larger portion of the surplus, as these firms are compelled to devote more revenue to advertising. Amazon has also raised FBA fees to cover logistics costs, including for heavier or larger items, for carrying low inventory, and for high return rates.

As a result, Amazon’s cut of seller revenues has steadily grown every year, increasing by a total of roughly 49% since 2016. Annual revenue from fees is now as much as $185-billion – more than twice AWS revenue, and seven times greater than AWS profits.22 These fees are nearly sufficient to cover all operating expenses for Amazon’s logistics and retail system, as well as all new investment.23 This means that Amazon can use the revenue from fees to cover fulfillment costs for its own inventory, allowing it to undercut competitors by selling at lower prices. Importantly, the increasing fees 3P sellers face have not led to higher market prices for their products. Instead, these fees have intensified downward pressure on costs, leaving North American sellers unable to compete with Chinese and other firms with lower costs. Consequently, most of the largest sellers on Amazon today are Chinese.

The globalization of Amazon’s supplier and seller value-chain has been reflected in the expansion of Inbound Cross-Dock (IXD) facilities, which receive and store inventory from foreign vendors. In order to streamline the flow of newly imported commodities into Amazon’s FC network and minimize transportation time, IXDs are located as close as possible to major ports. In addition to receiving shipments, these facilities also act as “buffers,” holding goods until FCs need new inventory. At that point, commodities are aggregated onto trucks and distributed to the appropriate FC locations. IXDs are thus structured to ensure the continuous flow of commodity capital into Amazon’s logistics system, reducing the risk of interruptions caused by delays or uncertainties in international shipping and maximizing circulation velocity.

Far from Amazon’s market power leading to higher monopoly prices, therefore, competitive disciplines have driven the globalization of Amazon’s value chain, the intensification of time-space compression, and forced prices down. Indeed, Amazon has engaged in ruthless price competition to undercut its rivals. As we have seen, Amazon’s very structure internalizes price competition, including through its e-commerce marketplace where a vast range of commodities compete for consumers’ dollars. Amazon has consistently ranked as the lowest-price retailer since 2016. In 2023, Amazon’s prices averaged 4% lower than Wal-Mart’s for identical products and were a whopping 16% lower on average than rival retailers overall. That 70% of Amazon and Wal-Mart products have identical prices today suggests a process of price slashing and convergence at a lower level.24 This clearly challenges the idea that Amazon, Wal-Mart, and other retail giants can be seen as monopoly firms setting prices through oligarchic collusion.

In addition to extracting fees and negotiating favorable wholesale prices, Amazon’s control over commodity capital enables it to accumulate a monetary hoard, which helps it to finance its very high levels of investment. As it controls capital at the moment surplus is realized (i.e., at the point of sale), Amazon regulates the reflux of this money back to suppliers and sellers. By “damming up” the circulation process, and temporarily preventing the money in which surplus value has been realized from flowing back to suppliers and sellers, Amazon accumulates a monetary hoard. It then transforms this hoard into money-capital, setting it in motion within merchant and productive circuits. The quicker Amazon sells products and receives money, and the longer it defers payment to its suppliers and sellers, the more this hoard grows.

Amazon amasses this fund by managing the difference between the circulation time it achieves in absolute terms and that which it imposes on its suppliers. In effect, Amazon passes on only a portion of the total gains in circulation time to its suppliers, though this reduction must still be sufficient to provide suppliers with a competitive incentive to rely on Amazon for the circulation of their commodity capital. Recall that circulation time = selling time + buying time. While Amazon reduces the overall circulation time, it speeds up selling time more than buying time – quickly converting commodity-capital into the money-form (selling time), and then freezing the circulation process and retaining this money under its control for a certain duration (buying time). By holding cash owed to suppliers, Amazon gains continuous access to interest-free capital, while displacing the debt and interest load onto weaker supplier firms.25

The profitability of AWS, as well as Amazon’s strong cash position and minimal debt, are widely recognized as key factors supporting Amazon’s high share price. These factors have enabled Amazon to sustain this high market valuation even without conducting dividends or buybacks as other large corporations do. Amazon is one of only five companies today with a market capitalization (i.e., total value of outstanding shares) exceeding $2-trillion, yet it has never paid a dividend. In contrast, Apple, another $2-trillion company, spent half a trillion dollars on buybacks over the last decade. Wal-Mart has devoted $102-billion to buybacks since 2009. Meanwhile, Amazon spent only $7.2-billion on buybacks over the same period. Avoiding transferring surplus to investors through such mechanisms allows Amazon to retain these funds, further strengthening its liquidity position and supporting its high levels of investment.

Investment and Market Power

Amazon’s control over the channels through which its network of sellers and suppliers distribute and store commodity capital, and realize surplus value, has enabled it to absorb these ostensibly “independent” capitals. Insofar as these capitals operate as extensions of Amazon, their investments are, in essence, investments in Amazon itself. Amazon’s ability to provide opportunities for these capitals to profit “independently” supports a specific form of centralization in which value is continuously funneled into Amazon through various fees and payment conditions, while sellers and suppliers retain a share of this value in the form of “independent” profits. Through this structured relationship, Amazon collects fees and interest-free loans from suppliers which together are nearly sufficient to finance all new investment as well as day-to-day operations. The profitability of AWS and its integration with Amazon’s logistics is especially critical for its strength.

Amazon’s competitiveness is rooted in the exploitation of labour. Strict work discipline is essential for accelerating circulation velocity and reducing circulation costs, which underpin the firm’s market power and accumulation of surplus. It is this which incentivizes 3P sellers to pay increasing fees and 1P sellers to sell inventory at low cost, and which enables the reproduction of the firm’s monetary hoard. Insofar as Amazon’s market strategy for AWS depends on leveraging this efficiency, the competitiveness of that business, too, hinges on labour exploitation. Amazon also engages in productive activities. Intensifying work and increasing labour productivity thus not only minimize circulation costs for supplier and seller firms, but are also means for producing surplus value. Given that Amazon’s transportation and logistics operations add value to commodities, competition with brick-and-mortar retailers especially compels the company to intensify exploitation to keep prices low.

That Amazon’s competitive position hinges on the exploitation of labour has led it to undertake massive R&D expenditures to improve productivity, in addition to “filling up the pores of the working day” by limiting breaks and free time.26 Amazon is today the leading corporate R&D spender – surpassing, for example, high-tech and aerospace companies.27 This spending is heavily focused on improving the productivity of labour through robotization, artificial intelligence, and algorithmic discipline and coordination. The deskilling and intensification of the labour process through such means facilitates the acceleration of circulation velocity, reduction of circulation costs, and production of surplus value. Additionally, insofar as wage goods are purchased on Amazon, the cheapening of these commodities eases pressure for wage increases among all workers and facilitates the production of relative surplus value across the economy.28

Amazon’s strong emphasis on R&D investment challenges the idea that it is a non-competitive monopoly firm. In the absence of competition, Amazon would have little incentive to undertake technological innovation. The reality, as we have seen, is quite the opposite. Amazon has been compelled to reproduce its market power by continuously developing – even revolutionizing – the technical bases of production and circulation. This underscores the persistence of competitive pressures bearing down on Amazon. Indeed, the market position of any dominant firm emerges and must be continually defended through an ongoing war among all capitalist firms. Any temporary reprieve that barriers to entry may provide to dominant firms should not be overestimated, as inefficiencies resulting from the use of outdated methods or technologies can be exploited by rival firms and new market entrants.

Amazon’s very high levels of investment and other strategic maneuvers have established the firm as an economic juggernaut, and make it very difficult for other capitals to challenge its dominant position. Amazon’s continuous development of the technical bases of production and circulation mean that any potential rivals must undertake extremely high fixed costs in order to pose a serious challenge. In addition to financing its own in-house R&D operations, Amazon operates an internal investment fund for undertaking strategic acquisitions of firms that have developed critical new technologies. The fact that Amazon can purchase these firms without needing to borrow, but can do so effectively “for free,” constitutes a major competitive advantage. The objective, of course, is to ensure that Amazon controls any innovative technologies that could potentially challenge its dominance.

Amazon has supplemented the low margins of its retail business through aggressive diversification, including investing in AWS as well as major acquisitions in media and streaming services. These operations are strategically integrated such that the whole is more valuable than the sum of its parts. Thus, Amazon entered the streaming video sector as the market leader, surpassing Netflix, as its 200 million Prime members were automatically subscribed to Prime Video (which is now also being offered as a standalone service, including versions with and without advertising at different price points). Amazon’s purchase of MGM also yielded not only a high-margin business but also one that has been vertically integrated with its streaming service, producing content that can be cheaply featured on its platform.

Mainstream economics assumes that competition declines as the units of capital become larger, with “perfect competition” giving way to increasingly “imperfect” competition over time. The reality, as Marx argued, is that larger investment in fixed capital does not impose insuperable barriers to entry. On the contrary, the organization of capital on an increasing scale into gigantic corporations tears down barriers to the operation of the forces of competition. This especially the case as the financial system enables the competitive circulation of investment and allocation of credit across all sectors of the economy.29 As a result, while “a growing number of relatively small capitals will be forced to the wall, those larger capitals that continue to survive and expand will continue to do battle on an ever-enlarging scale.”30 Far from monopolistic stagnation, competition constantly drives the dynamic restructuring of all economic sectors through the development of new technologies, new organizational forms, new substitute products, and new entrants.

The case of Amazon perfectly illustrates how market power and economic concentration do not negate capitalist competition. Despite the conclusions of mainstream economists and policymakers as well as some on the left, it is impossible to conclude that Amazon’s power has in any way mitigated the forces of competition.31 As we saw, Amazon defends its dominant position by investing to build up and reproduce barriers to entry, preventing other capitals from replicating its structure and challenging its market dominance. However, Amazon also demonstrates the ephemeral nature of these barriers and the continued dynamism of capital even in the most concentrated markets. As Amazon enters and competes across sectors, it challenges what might be seen as the most monopolistic firms, not only including Wal-Mart, but also Netflix, Microsoft, Google, FedEx, and Disney.

Amazon thus not only exemplifies the turbulent process of achieving market power but also highlights the reality that even a dominant market position is always only partial, and must constantly be defended amid the relentless competitive dynamics of capitalist restructuring and innovation. A decade ago, it might have been argued that FedEx and UPS held monopolistic positions; today, Amazon delivers more parcels than either of these firms.32 Similarly, Wal-Mart’s market position might have been thought unassailable before Amazon totally upended the retail sector based on a combination of technological change, organizational innovation, and market strategy. Equilibrium and stasis are myths of neoclassical economics textbooks; they bear no resemblance to the reality of modern corporate capitalism.

Crucially, this means that Amazon is vulnerable. Amazon has constructed a unique infrastructure for efficiently circulating commodity capital. Yet this uniqueness should not be overstated. Amazon’s model could be replicated or replaced, and it faces relentless pressure from other firms racing to accelerate circulation and delivery. Some aim to improve their own logistics, while others form partnerships with firms such as UPS, DHL, and FedEx offering 3PL or delivery services.33 In fact, the integrated nature of Amazon’s model means that a challenge could have wide-ranging effects on its market position. Furthermore, as Amazon increasingly markets “unknown” products from low-cost 3P sellers, space has opened for rivals to emerge in particular markets.34 Though possibly offering slightly longer delivery times, consumers may perceive these alternatives as more reliable. Meanwhile, it has sought to undercut competitors through price competition, which is internalized within the firm’s very structure.

In theory, there should be significant space for workers to win wage increases from monopoly firms, whose very high profit margins mean that they may be willing to trade increased labour costs in exchange for labour peace – effectively “buying off” workers with higher wages. Moreover, their so-called “monopoly pricing power” would supposedly allow them to pass on higher wages by raising prices. That Amazon continues to face competitive pressures, on the other hand, means that we should not be surprised by its ruthless suppression of worker struggles. But this also points to opportunities for workers to disrupt the firm’s operations. If Amazon’s competitiveness depends upon its ability to compress circulation time, impeding the rapid circulation of commodities by slowing down or even altogether suspending the functioning of variable capital – that is, labour – would seem to be a potentially powerful weapon.

At the same time, as Sam Gindin has pointed out, Amazon’s ability to sustain significant surplus capacity through massive investment allows it to circumvent and undermine smaller-scale or more limited blockages such as those envisioned within the “choke-point” approach that has become influential in strategic discussions about working class power in the logistics sector.35 Absent the formation of large groups of organized workers capable of undertaking a larger-scale and longer-term disruption, this view holds, the most effective strategy is to mobilize smaller numbers of militant workers positioned at strategic points within the production-circulation process. Yet if Amazon can quickly and cheaply redirect the flows of commodity capital elsewhere, such a strategy seems more like a recipe for guaranteed defeat, which can only result in dampening worker activism rather than catalyzing a broader struggle.

But, as Gindin also emphasizes, scale alone is not enough. Restricting worker activism to routine collective bargaining, as in the “business unionism” model of the large unions, grants Amazon ample time to prepare for strikes or other job actions, ensuring that it operates from a position of strength. The adaptability afforded by Amazon’s investment strategy means that workers must build equally dynamic capacities for disruption. Amazon’s model of minimizing delivery time by warehousing goods near major urban centers highlights the potential effectiveness of a regional organizing strategy, in which workers maximize their leverage within specific zones of circulation. And, given Amazon’s imperative to accelerate circulation, such struggles would be most effective if they extend beyond wage bargaining to demands for greater control at the shop-floor level. All this points to the need for a fundamentally different organizing model than that of the big unions.

FCs are central to Amazon’s circulation of commodity-capital: receiving inflows from sellers and suppliers and holding the bulk of the inventory, which flows out to SCs and delivery centers once it is purchased. As such, they are critically important for sustaining its competitive dominance through the continuous compression of circulation time and have particular strategic significance. Yet the scale of these facilities suggests that it is not sufficient to merely mobilize a “militant minority” of workers to wield power there; rather, this requires broad and deep organizing to mobilize large numbers of workers. Moreover, Amazon’s dominance ultimately rests upon the efficiency of its entire logistics operation, from the time it gains possession of commodity-capital to the moment goods are transported to the consumer’s door. It is therefore possible for workers to exert pressure on Amazon in a variety of different ways – or, better yet, at many points simultaneously. •

This report was prepared for Amazon Workers Solidarity (AWS).

Amazon Worker Solidarity is a community group working to bolster the movement to organize Amazon workers. To join this independent grassroots effort or find out more, AWS can be contacted at amazonworkersolidaritygta@gmail.com.

Endnotes

- John Weeks, Capital and Exploitation, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981.

- Anwar Shaikh, Capitalism: Competition, Conflict, Crises, Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 158.

- Howard Botwinick, Persistent Inequalities: Wage Disparities Under Capitalist Competition, Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2018, pp. 152-153.

- Stephen Maher and Scott Aquanno, The Fall and Rise of American Finance: From J.P. Morgan to BlackRock, London: Verso Books, chapter 2.

- Karl Marx, Capital Volume 2, New York: Penguin Books, 1978, p. 153.

- Marx, Capital Volume 2, pp. 226, 185.

- David Harvey, “Value in Motion,” New Left Review 126 (November / December), 2020.

- Marx, Capital Volume 3, p. 136.

- Marx, Capital Volume 3, p. 379-380.

- David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 1991.

- Karl Marx, Capital Volume 3, New York: Penguin Books, 1981, p. 381-382.

- Marx, Capital Volume 2, p. 176-177.

- Marx, Capital Volume 2, p. 227.

- Marx, Capital Volume 2, p. 135.

- Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity.

- Cedric Durand, How Silicon Valley Unleashed Techno-Feudalism, London: Verso, 2024; Yanis Varoufakis, Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism, Pittsfield, MA: Melville House, 2024.

- Spencer Soper, “Amazon Prime Membership in US Gain 8% to New High After Lull,” Bloomberg, 16 April 2024.

- Sebastian Herrera, “Amazon Overhauls Delivery Network to Dispatch Packages Faster, More Cheaply,” Wall Street Journal, 13 May 2023.

- Liz Young, “Amazon is Reviving Its Logistics Expansion and Reshaping Its U.S. Distribution,” Wall Street Journal, 22 May 2024.

- Annie Palmer and Lauren Feiner, “Amazon sellers sound off on the FTC’s ‘long-overdue’ antitrust case,” CNBC, 6 October 2023.

- Federal Trade Commission, Amazon.com Inc, Amended Complaint, 15 March 2024.

- Stacy Mitchell, “Amazon’s Monopoly Tollbooth in 2023,” Institute for Local Self-Reliance, September 2023.

- Amazon’s operating expenses in 2023 were approximately $234-billion, including $146-billion in SG&A expenses as well as $86-billion in R&D. As noted, Amazon collected approximately $185-billion in fees from third-party sellers. Additionally, we estimate that the cash hoard Amazon accumulates through its low CCC amounts to as much as $30-billion annually.

- As would be predicted by Shaikh’s theory of “real competition.” See: Profitero, Price Wars: 2023 U.S. Edition, November 2023.

- This differential can be measured in terms of what mainstream economists call the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC). CCC quantifies the difference between the time a firm’s capital is tied up in the form of commodity capital and the time it takes to pay suppliers. CCC is expressed in the formula: Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) = Days of Sales Outstanding (DSO) + Days of Inventory Outstanding (DIO) – Days of Payments Outstanding (DPO). DSO is the time it takes a firm to collect payment from customers after a sale; DIO is the time a firm holds inventory before it is sold (known as “inventory velocity”); DPO is the time it takes a firm to pay its suppliers.

Thus in Marxian terms: circulation time = DSO + DIO + DPO + t1 + t2, selling time = DSO + DIO + t1, and buying time = DPO + t2 (where, in the case of a merchant capitalist firm such as Amazon, t1= the time necessary to transfer the commodity-capital from the productive capitalist to the merchant, and t2 = the time necessary for the productive capitalist to purchase labour-power and means of production).

The lower the CCC, the longer a firm holds on to cash after selling its inventory and receiving payment, but before paying its bills. A firm’s leverage over suppliers and customers can therefore be reflected in a low CCC, indicating the relative power of a firm to demand or delay payments owed. Additionally, a low CCC is often correlated with a higher share price. Tellingly, Amazon has among the lowest CCCs of any major corporation. At year-end 2023, Amazon posted a CCC of -14.7, as compared to the retail sector average of +44.9. In the same period, Amazon’s main competitor, Wal-Mart, posted a CCC of +8.7. - Karl Marx, Capital Volume 1, New York: Penguin Books, 1976, p. 534.

- Brian Buntz, “Top 30 R&D spending leaders of 2023: Big Tech firms spending hit new heights,” R&D World, 17 June 2024.

- Michael Lebowitz, Beyond Capital: Marx’s Political Economy of the Working Class, Second Edition, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

- Botwinick, 153.

- Maher and Aquanno, The Fall and Rise of American Finance.

- Durand, especially Appendix II; Lina Khan, ‘Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,’ Yale Law Journal, 126:3, 2016.

- Chris Morris, “Amazon is set to deliver 5.9 billion packages this year – more than UPS or FedEx in a big reversal,” Fortune, 27 November 2023.

- Young, “Amazon is Reviving its Logistics,” 2024.

- “Global Pet Care E-Commerce Market,” Research and Markets Report, 2024; “Retail market share of consumer electronics sales held by Amazon in the United States from January 2023 to December 2023,” Statista, 2024; “Retail market share of home improvement sales held by Amazon in the United States from January 2023 to December 2023,” Statista, 2024.

- Sam Gindin, “A Generational Challenge: Taming Amazon, Renewing Labour,” The Bullet, Socialist Project, 20 May 2024.