Sudan: From Revolution to War

On 15 April 2023, violence erupted in Sudan’s capital Khartoum following weeks of growing tensions between the leader of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the head of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (known as Hemedti). Amidst the power struggle between the rival factions that make up the military government, hundreds of people have been killed, thousands injured and millions displaced.

Red Pepper speaks to Muzan Alneel, a Sudanese writer and public speaker based in Sudan, about the current war, how it links to the revolutionary uprisings of 2018-19 and what the future holds for the country.

Credit: Manula Amin, Tom Lynton.

Red Pepper (RP): What is happening in Sudan today?

Muzan Alneel (MA): There’s a war taking place in a number of Sudanese cities between the Sudanese armed forces (SAF) and the para-governmental militia of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). The latter was formed in 2013 at the behest of then-president Omar al-Bashir, who was in power from 1989 to 2019.

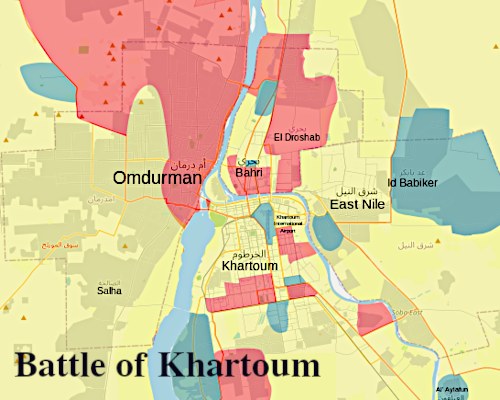

Today, Khartoum, the capital, Nyala and other cities are war zones and ghost cities. Civilians are being killed by the RSF raiding homes, by SAF planes randomly striking residential areas, by a lack of healthcare and medication. Some have also died of hunger and thirst in their homes as war damage has stopped running water – some water stations are occupied by the RSF. Both parties claim victory is near, but on the ground, the violence remains overwhelming.

Sudan has suffered from war in various parts of the country in the past, and while for decades conflict was expected to reach the capital, it was only in recent years, as the RSF’s political power grew, that we saw signs that the war would involve different militias of the government (SAF and RSF).

In a 2014 interview, the leader of the RSF, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, popularly known as Hemedti, made his ambitions clear: ‘We are the government, and the [official] government can talk to us when it gets itself an army.’

RP: In 2018-19, we watched mass uprisings bring an end to Omar al-Bashir’s 30-year dictatorship. How were these uprisings successful and were there warnings that a subsequent conflict would emerge?

MA: The 2018-19 uprising was not Sudan’s first against al-Bashir. In 2013, when the RSF were first brought into Khartoum, it was to suppress protests against the regime. Hundreds of people were killed then too. But the uprising of 2018-19 was more successful for a number of reasons.

Firstly, the economic context was dire. Poverty was widespread and the country’s small middleclass had a stranglehold on what little resources were available. In this context, a new political body – the Sudanese Professionals’ Association – was created, which captured public sentiment against the regime and was able to act as a vehicle for change. Finally, the use of decentralised organising mechanisms such as local neighbourhood committees facilitated direct political action for many previously alienated sections of society.

The first four months of peaceful protests were hugely indicative of people power in action: they forced the toppling of al-Bashir by his generals in a coup d’etat. Following this, power was transferred to a ‘transitional military council’, but this council did not represent the demands of the people and there were weeks-long sit-ins around military headquarters across the country demanding a fully civilian government.

In the face of the military council’s violent attempts to disperse protesters, people showed resilience and collective strength. But counter-revolutionary parties in and outside Sudan pushed for a quick solution, which effectively stopped the people’s movement through the August 2019 agreement. This agreement, forged by a distrusted political elite, the military and a civilian government, meant the heads of the military council would not be held accountable for the crimes they had committed against the protesters.

This sanctioned impunity unsurprisingly led them to commit more. The killing of protesters, oppression and economic malpractices that brought people to the streets in the first place in 2018 have simply continued.

It is also important to note that external powers have in recent years been very influential in Sudanese politics. The RSF’s power, for instance, had been bolstered by the ‘Khartoum process’, an agreement that started in 2014 between the European Union and the Sudanese government, that funded the RSF to prevent migrants hoping to eventually reach Europe via crossing Sudanese borders.

RP: What would you say has been the historical role and impact of foreign interventions leading up to the current situation?

MA: International and regional support from actors such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE, UK and US was critical in the creation of the repressive partnership government and legitimising military rule – especially when it was clear just how committed people were to delivering a civilian government.

For instance, in May 2019 the Sudanese working class executed a countrywide two-day strike demanding an end to the military regime. Sudan was at a standstill. Airports, markets, oil fields, and mines were all closed.

Another example was seen following the 3 June 2019 massacre in Khartoum as armed forces of the Sudanese military council violently dispersed protesters who took part in sit-ins. At least 100 people were killed and 700 injured. Yet in the wake of such a harrowing event, despite a countrywide internet shutdown, neighbourhood resistance committees formed coordinating bodies between neighbouring committees. This also led to a march of millions of people across the country who continued to carry the demand for an end to military rule.

However, people were up against a powerful propaganda machine propagated by the UAE and Saudi, that heralded the ‘Sudanese model’ of criminal partnership. Facilitated by pro-status quo internal and international actors, lip service was paid and awards were presented by reformist think-tanks and diplomats.

Claims were made that those in power would realise the goals of the revolution. People who rejected the policies enacted by the partnership government made up of the military and the transitional government of Sudan – policies that closely resembled al-Bashir’s – were labelled opponents of the ‘government of the revolution’.

Certainly, the partnership government would not have formed or lasted as long if not for international powers. This is the very purpose of this type of international intervention: to preserve the status quo, to end revolution. Hypocritically, diplomats and institutions that designed and pushed for the structures that led to the massacre, the coup and current war, are still openly discussing the ‘future of Sudan’.

It is shocking how many can die due to international diplomacy’s flawed methods. There’s no accountability, no matter how many wars and oppressive regimes they facilitate.

RP: Do you feel that the hopes and aspirations fought for during the 2018-19 uprisings remain among the people?

MA: Despite the government’s attempts to minimise the power of the resistance committees, they have not only survived but expanded and are now actively saving people’s lives. Within hours of the war erupting, these committees set up emergency rooms in local areas, providing essential healthcare facilities, issuing calls for healthcare workers, donations of medication and more.

Some emergency rooms started community kitchens, while others managed evacuations and coordinated the repair of destroyed power lines. Even outside war-affected areas, emergency rooms were created to manage the housing of those displaced due to the conflict.

People use and need grassroots organising to save lives. It is proof that the values of peace and justice that the popular protests fought for are still alive.

RP: In mainstream media there’s a lot mentioned about ‘finding solutions’ but much less engagement with how people wish to build a more socially-just Sudan. What are the dangers of this?

MA: The mainstream media is designed to inform us about the elite, and suppress the people. When the transitional government adopted the same economic policies of al-Bashir’s toppled government, instead of examining the resultant hardship, mainstream headlines focused on visits by western diplomats. When hundreds of protests took place against the transitional government’s policies and the impunity of the military generals, they were ignored.

Or take the solutions that people are coming up with in the face of war. In the example of hospitals today, media outlets might report on a handful of doctors, depicting them as heroes, all the while ignoring the fact these hospitals are being run by the power of the people. It’s popular organising that operates these hospitals and even pays doctors their salaries.

RP: What does the future look like?

MA: This revolutionary path that the Sudanese resistance is taking against the war, the path of popular organising to save lives, has great potential. Depending on how these efforts go, we may start seeing a more established route to popular governance that moves beyond emergency provision of services. We are seeing some of this taking form.

However, a lot of factors need to change and much effort is needed before a system of popular governance becomes possible. This includes the formation of an organised political body that advocates, theorises and organises for people’s power.

Meanwhile, we should not expect international diplomacy – and the vacuous power sharing agreements and military impunity they support – to bring meaningful change to the people of Sudan. Ultimately, it is not the task of the Sudanese people to teach the counter-revolution about their mistakes. They are very aware of them.

The task of revolutionaries is to understand reality and, through that process, develop methods to advance the goals of the revolution: freedom, peace and justice to the people. •