The Budget and the Canadian Housing Market: Another Ruined Dinner Party

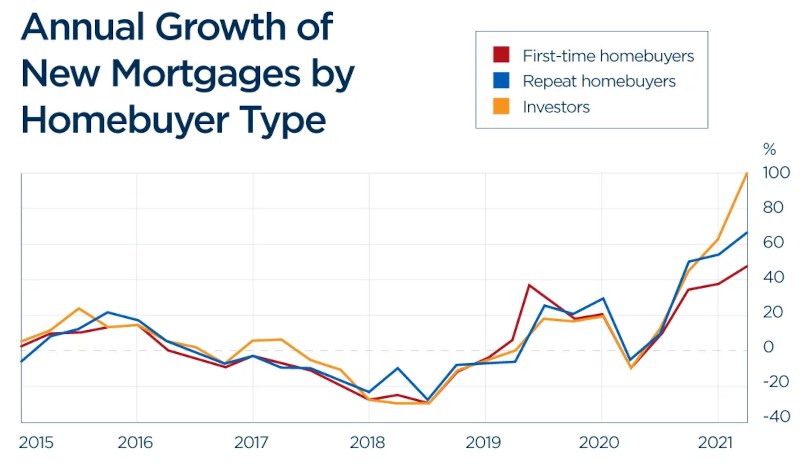

Chrystia Freeland put on her best smile to introduce two new bonbons she hopes will sweeten the lives of Canada’s first-time home buyers.

On 11 April, Canada’s deputy prime minister and minister of finance, announced that first time buyers could withdraw up to $60,000 (up from $35,000) from their RRSP savings accounts to put toward a down payment for a house. This can be combined with savings up to $40,000 in a home buyer’s Tax Free First Home Savings Account. Of course the real question is how many younger people have any substantial savings for a down payment which is typically 20% of the price of a home? The average price of a house in Canada is $720,500. A 20% down payment for that home is $144,100. The average house price in cities such as Toronto, Vancouver and Calgary is often double that amount.

Unless people have parents’ help, it’s unlikely younger people have tens of thousands of dollars for a down payment. Assuming, the house cost $720,500 less the down payment of $114,100, that leaves a mortgage balance of $576,400. The homeowner will have to pay more than $3300 a month in mortgage payments alone – plus another thousand dollars each month for utilities and taxes.

Freeland also said that lending institutions would extend mortgages on newly built homes by five years, to 30 years rather than the typical 25 years. Sounds good? Well, it does mean lower monthly payments, which could help a lot of cash strapped Canadians whose wages have not kept up with inflation. But it will also mean windfall profits for banks and lending institutions.

Here is how. I used the TD Mortgage calculator, and assumed a $691,680 mortgage at a 3-year fixed rate of 5.71%.

Over 30 years, the new homeowner would pay $3324/mo = $1,196,640

Over 25 years, the new homeowner would pay $3589/mo = $1,076,700

A homeowner opting to pay over 30 years would pay less per month (about $265 less), but more than $119,940 extra to the lender for their mortgage. That works out to 28% again as much as the price for the house.

Still, with the 30 year rate, the owner will pay $265 less per month, and save nearly $3200 per year.

So who is making money from Freeland’s good news’ 30 year mortgages? Why banks and private lending institutions – that’s who and they are making out like bandits. Return on Investment (ROI) is calculated by profit earned divided by the cost of investment. The higher the percentage, the more money the company makes.

On average, over the last nine quarters from 2022 to the end of January 2024, RBC’s ROI was 16.88%, Bank of Montreal’s ROI was 15.97%, and the Bank of Nova Scotia’s ROI was 11.11%. Financial experts tell us a ROI of 5-7% is reasonable, but anything over 10% is “strong.”

Here is a chart that shows the three banks’ ROIs January 2022-2024, alongside their gross profits for for 31 Jan. 2023-31 Jan. 2024:

| Three Canadian Banks | ROI: Jan 2022-Jan 2024 |

Gross profits 31 Jan. 2023-31 Jan. 2024 |

increase year over year | decrease year over year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC | 16.88% | $40.384-Billion (Can.) | +3.68% | |

| BMO | 15.97% | $24.004-Billion (Can.) | -3.58% | |

| Bank of NS | 11.11% | $24.268-Billion (Can.) | +1.21% |

The other issue is that the 30 year mortgages are only available for those who purchase newly built homes – so Freeland is also throwing a giant bone to developers, construction companies and builders. Clearly the government wants to encourage new builds.

Of course the problems with new builds are the cost both financially and the cost to the environment. The demolition of older buildings “including the embodied energy of what is demolished and the energy consumed in construction” becomes a problem. There are fabrication of new materials such as glass and steel, the effects of the materials on the environment, and the gross profits made by developers and construction companies. When people call for affordable housing – virtually no new builds in the private sector are “affordable” – by affordable I mean rents or housing charges that account for 30% or less of the resident’s gross income.

Carl Elefante, former president of the American Institute of Architects, said: “The greenest building is the one that already exists.” In 2016, the US National Trust for Historic Preservation found, through a series of case studies, that,

“it takes between 10 and 80 years for a new building that is 30 per cent more efficient than an average-performing existing building to overcome, through efficient operations, the negative climate change impacts related to the construction process.”

So what have we got across Canada? The governments’ undeniable penchant for funding new developments, houses, townhouses, apartments means higher costs to new owners or to tenants. New developments also cost in terms of delivering infrastructure for utilities such as water, gas, electricity, transit and building schools and amenities for never-before serviced areas.

Yet the building is going on apace.

Buildings for the Climate Crisis: a Halifax Case Study

Environmental researcher and writer, Peggy Cameron, in her landmark report here, notes that in Halifax from 2003-2020,

“the city issued 2,535 demolition permits estimated to be equal to the area of 17 city blocks. … And while the demolition average for Halifax during this period was 140 buildings each year, the annual number of squandered buildings and materials has been steadily increasing, with 101 permits granted in 2003 compared to 188 in 2020.”

In every city many older buildings that are empty, or unused merely need upgrades then can be converted to housing. But that is not what we see overall. We see demolitions of existing and older housing that is affordable to make way for high end condos and new skyscrapers.

Nearly 40% of Spryfield residents live in unsuitable, inadequate or unaffordable housing

Spryfield, a middle-class suburb of Halifax, has seen 39% of its most affordable rental homes disappear from 2016 to 2021. The latest census data shows 42.2% of Spryfield’s 8,358-person population are renters, and 39.7 per cent of those people live in accommodations considered unsuitable, inadequate or unaffordable under Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) standards.

Our governments are wedded to the idea that new is better; fast builds are better and “if you build it they will come.” I doubt that boosting the middle class’s tax free home savings accounts will help, nor do I think a 30 year mortgage will appeal to most people. •