What Kind of Holocaust Education? Preventing Racism and Antisemitism

As we mark the 19th Annual Holocaust Remembrance Day [27 January], the call to make Holocaust teaching “obligatory” in Canadian public schools has risen to fever pitch. British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario have responded with firm promises to do so. The Montreal School Board has requested that Quebec copy the idea. And B’nai Brith Canada is demanding that other provinces follow suit.

Why the current panic about Holocaust education?

Echoing other politicians, Premier David Eby said BC’s move was in response to the 7 October 2023 Hamas attack on Israel and the subsequent (reported) rise in antisemitism. He also declared, “Combatting this kind of hate begins with learning from the darkest parts of our history, so the same horrors are never repeated,” and promised to consult with Jewish groups like the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre to implement the curriculum changes. (One of Eby’s cabinet ministers, Selina Robinson, was a key protagonist in the BC move and recently resigned for outrageous anti-Palestinian racist remarks.)

Certainly, the Nazi genocide against millions of Jews, Roma, and other ethnic/religious groups as well as LGBTQ, disabled people, socialists, and communists is a world historical phenomenon of immense importance, especially when considered alongside other genocides, particularly those in recent years and those that continue. And there is little debate that we should avoid letting knowledge of the Holocaust fade as the last survivors die off. But several other nagging questions arise: Why the emphasis on compulsion at this very moment? And, more to the point: how useful is the Holocaust in teaching anti-racism and preventing other genocides?

Report Claims Ignorance of the Holocaust, but Teaching is Widespread

In fact, moves to mandate Holocaust education predate October 7, 2023. They followed a much-publicized 2022 report by the lobby group Liberation 75. That report claims that respondents in grades 6 through 12 in Canadian and US high schools are largely uninformed about the mass murder of Jews by the German Nazi regime. Nearly 33 per cent of the students were reported to feel the Holocaust was fabricated or exaggerated. Many respondents said they learned about the Holocaust from social media, movies, TV, comics, and video games. It’s not that Holocaust education is absent in our schools. Rather, warns the report, it’s not “compulsory,” and, the report insists, it should be.

Actually, the Holocaust has been widely covered in Canadian school curricula for a long time. For example, it has been taught in the Toronto and District School Board for over forty years. Since 1987, Ontario’s curriculum has specified “The background and scope of the Holocaust” as part of the senior “Twentieth Century World History” course. In 1992, that expanded to explore the Holocaust more deeply, with topics like “World War II Part I – The Nazi Revolution,” “Why Hitler? Why Germany?” “The moral problems of the Nazi regime as embodied in the Holocaust,” “An analysis of the rationalization of evil. Is anyone innocent?” and “Demonstrate an understanding of the key factors that have led to conflict and war…and genocides, including the Holocaust.”

Vancouver’s first high school Holocaust education symposium for students was in 1976, Calgary’s in 1984. A McGill Master’s thesis reported that by 2016 there were twenty Holocaust education centres involved in helping school boards in Canada.

British Columbia’s official Grade 12 Social Studies curriculum has included a unit on “Genocide Studies” which deals with indigenous peoples and cultures; Armenian genocide; anti-Semitic pogroms; Soviet Union and Ukraine (Holodomor famine); Japanese occupation of Korea and China; the Holocaust; Khmer Rouge in Cambodia; Rwanda; Sudan; Guatemala; Yugoslavia. But it is technically true to say that some students could miss this course. Much has been made of the half-truth that a student could get through high school without receiving instruction on the Holocaust.

On 2 November, 2023, the CBC quoted a Manitoba government spokesperson, saying, “Holocaust education is taught in Manitoba as part of the social studies curriculum in grades 6, 7, 9 and 11.”

The CBC goes on, “For example, in Grade 6, Holocaust education is in the curriculum covering Canadian history from 1867 to the present day. In Grade 11, the history of Canada includes the study of the Second World War and the Holocaust.”

Despite this, Winnipeg’s Belle Jarniewski, executive director of the Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada and member of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, told the CBC she would give her province a “failing grade.” Why a failing grade, despite Holocaust curriculum in four Manitoba elementary and secondary grades?

The reason, responded Jarniewski, is that “[r]ight now we are seeing an explosion of antisemitism, as there has been every time that there is a war or a conflict in the Middle East. We feel the pushback here. Jewish parents are worried about the safety of their children. Adults are worried about their own safety, and some are afraid even to self-identify as Jews.”

Does Holocaust Education Teach Anti-Racism?

Aha!

But is Holocaust education only about the Jews? Proponents insist that anti-racism is a side benefit. Whether Jews themselves are a “race” is a subject better left to a different occasion. Suffice it to say that fighting antisemitism and fighting racism are at least theoretically linked. Liberation 75 founder Marilyn Sinclair, who also demands “mandatory” education measures, maintains that “the lessons of the Holocaust are not just about what happened to Jews.”

The major Jewish Canadian institutional organizations and several others devoted to this topic alone all offer programs of training and advice on public school curriculum on the Holocaust. All of them assert that, in addition to countering antisemitism, this training will have the added benefit of reducing other forms of bigotry.

Indeed, Marvin Rotrand, national director of B’nai Brith’s League for Human Rights, telling Quebec legislators in September 2023 to follow Ontario’s example of mandating Holocaust education, contended that “[n]ew research indicates that when Holocaust education is provided, hate crimes and incidents against Jews decrease significantly,” and that “making Holocaust education mandatory reduces hate incidents targeting other racial and religious minorities.” Rotrand cited preliminary findings of a study by RealityCheck Research. According to Rotrand, that source found US states with mandated Holocaust education had a drop of 55 percent in antisemitic crimes and that anti- Black, LGBTQ2+, Latino, and Muslim crimes also fell.

The legitimacy of RealityCheck is, however, dubious. Its CEO is US lawyer Daniel Pomerantz, who has very close ties to Israel. He launched Playboy magazine in Israel, and until recently headed the so-called “HonestReporting” (HR) organization (which has a Canadian subsidiary). Honest Reporting was founded in 2006 by Joe Hyams, a registered bureau speaker for the Israeli Embassy in Washington and Simon Plosker, a former spokesperson for the Israeli military and member of several pro-Israel organizations. HR has been called by the American Journalism Review “a pro-Israeli pressure group.” HR’s purpose is to find, critique, and attempt to contradict media items that cast Israel in an unfavourable light. It pursues that mission with a vengeance. Pomerantz’s link with RealityCheck may help explain the current insistence on mandatory Holocaust education.

Two recent articles in The Maple (“Meet The Billionaire-Funded Pro-Israel Group Influencing Media” and “Here Are HonestReporting Canada’s Billionaire And Millionaire Funders”) excoriate Honest Reporting Canada and its US parent, They quote HR Canada director Mike Fegelman claiming HR’s aim is “to create a digital army for Israel” and “to act as Israel’s sword and shield.”

Even if we accept the assertions of the Liberation 75 study on gaps in student knowledge of the Holocaust, we can see that the Holocaust is already widely taught in Canadian schools. So why do the proponents insist that it be made compulsory? And what does the word ‘compulsory’ mean, anyway, when it is already part of the curriculum? We will return to that presently.

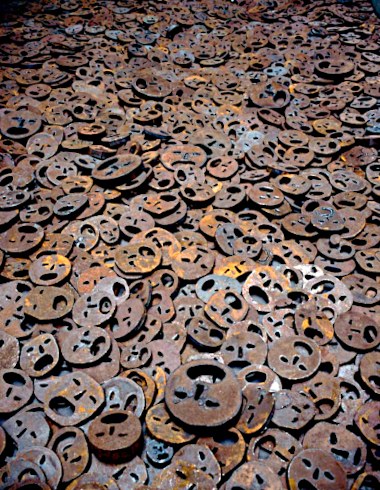

Full disclosure here: I am the Jewish son of a survivor of the Auschwitz Nazi concentration camp and have a very personal interest in the topic. Every day that I lived with my father, I saw the blue tattoo on his arm. I also saw it on the arms of his Holocaust survivor friends and relatives. Their stories became my stories. Their nightmares became my nightmares. They have marked me indelibly as they have many other Jews. For over a half century, I have wondered what sorts of lessons humanity can learn from these terrible events.

On the other hand, my personal exposure to the Holocaust helped form me as a social justice activist and a contrarian when it comes to all sorts of orthodoxy. A founding member of Independent Jewish Voices Canada, and a consistent critic of Israeli policies and practices, I also co-developed and have been teaching workshops on antisemitism to a multitude of learners for several years. And I am skeptical of the insistence that more knowledge of the Holocaust alone will deliver on the anti-racist promise, not least because some of the actions that Israel takes against the Palestinians cry out for comparison to some of what the Nazis did to the Jews.

Among my more recent reading in Holocaust literature, I read the full Third Reich Trilogy (2003-8) by British historian Richard Evans. At 2500 pages, this was definitely not a task for the faint-hearted. Other studies focus on single aspects of that regime, like Adolf Hitler, or the genocide of the Jews, or World War II. The recent Bystander Society: Conformity and Complicity in Nazi Germany and the Holocaust (2023) by Mary Fulbrook is a significant deep dive into a crucial question.

Only by looking at the entire picture of the Nazi regime can one begin to grasp how it came about and how it proceeded and to what extent it can or cannot teach us to be both non-racist and antiracist. Moreover, we need to examine how the Holocaust ties in with 20th century imperialism and colonialism.

But knowledge of the full picture of the Holocaust presents several fundamental dilemmas.

Fundamental Dilemmas in Teaching the Holocaust

The Holocaust is so immense a phenomenon, so horrible to contemplate, that it beggars the imagination. Studies of the efficacy of Holocaust pedagogy reveal that evaluation of its success is illusory.

Indeed, the dean of Holocaust scholars, Yehuda Bauer argues, “the Holocaust is too often turned into vague lessons of the danger of hatred or prejudice at the expense of really trying to understand the reasons and motivations for the genocide.”

A study by several researchers at University College London posits two alternative views of Holocaust education. On the one hand is the argument that general knowledge is more important than detailed understanding.

“A cursory overview of the Holocaust is sufficient for students to appreciate that this was a deeply troubling episode in modern history and one which sharply illustrates where prejudice and discrimination might lead if left unchallenged.”

On the other hand, the authors suggest an opposite view:

“This perspective claims that unless the historical Holocaust is more fully understood, there is a danger that students might acquire simplistic moral and universal lessons which, though well intentioned, typically will be ill-informed and fuel the prevalence of troubling myths and misconceptions.”

An upcoming entry on antisemitism education in the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia if Social Justice Education advises the following:

“One influential way of thinking about the Holocaust and about Holocaust education is the ‘particularist’ approach whereby the Holocaust is viewed as a unique and unprecedented event which must be studied in its singular historical context and with an emphasis on its devastating consequences for Jews and Jewish life. This approach may fail to derive lessons about universal human rights that can be applied across multiple locations and contexts. The ‘universalist’ view, on the other hand, posits that the lessons of the Holocaust extend far beyond those specifically relevant to antisemitism. While the universalist view of antisemitism and Holocaust education promises to instill an ethic of tolerance, respect for fundamental human rights and a rejection of racism, prejudice and totalitarianism, there is, remarkably, little empirical evidence that current educational programs actually achieve these ends.”

A 2021 Swedish review of the literature on Teaching and Learning about the Holocaust (TLH) reveals several deficiencies, among which are these:

- A lack of reliable studies that evaluate educational initiatives to prevent antisemitism,

- Few studies that have evaluated TLH for consistency of educational outcomes over time,

- A disconnect between educational research and other research orientations concerned with the Holocaust and antisemitism,

- A gap between descriptive studies and studies evaluating educational outcomes.

American neoconservative scholar Ruth Wisse herself questioned the efficacy of TLH in a 2020 article that castigates the simplification inherent in it:

“…the potential for corruption begins with the impulse to make the Holocaust a universal symbol of evil, Nazism synonymous with ‘hatred’, and Holocaust education a redemptive American pursuit…

“…Holocaust education as currently defined introduces Jews at their lowest point in history – as victims, humiliated, suffering, starved, pursued, despised, and turned to ashes. Nazi energy and ingenuity destroyed a third of the Jewish people, with the cooperation of others, transforming them into the burnt sacrifice of the liberal imagination. Who gave liberals the right to keep using the image of the Jews in this distorted way?”

One rationale for teaching about the Holocaust is undoubtedly the “scared straight” or “shock therapy” principle. US anti-crime advocates used to take “juvenile delinquents” to visit jails for a similar reason. In a 1978 American Academy Award-winning documentary film by the same name, murderers and armed robbers in the prison scream at, berate, and insult the youth. The film insists that the exercise was successful in deterring criminal behaviour. But several subsequent academic studies concluded that such practices actually increase the rate of the subjects offending, although the precise reason for that is not known. Polish law-enforcement authorities are known to have used visits to Auschwitz in the hopes of warning persistent criminals of the consequences of their misdeeds, with similar negative results.

Moreover, even if the prospect of prison were a deterrent to juvenile delinquents, how do we know that the fact of the Nazi Holocaust, or the prospect of something similar in the future, would deter, say, a confirmed white supremacist from hating Jews or people of color? I am unconvinced, as are others, that aversion therapy, as practiced on the anti-hero Alex (including being forced to watch footage of the Holocaust) in the classic film A Clockwork Orange works. Indeed, the point of Stanley Kubrick’s film is that it does not work.

Never Again What?

I have attended lectures by concentration camp survivors to university and high school students. One of those lecturers was Philip Riteman, a resident of my home-town Halifax, Nova Scotia. Riteman improbably survived Auschwitz by being big for his age and the lie another inmate told guards that Riteman had a mechanical skill. Riteman died in 2018 at the age of 96. The inevitable lesson Riteman and other raconteurs drew and draw is “Never again.”

But never again what? What is it that humanity must never do again? Never again knowingly commit mass murder of anyone? Never again allow dictators? Never again stand by silently while others are abused and slaughtered? Or does it really mean “Never again for the Jews?”

If the “never again” were any of the above and if a country’s level of abhorrence of mass murder were positively correlated to the level of knowledge of the Holocaust, then surely Israel would be one of the countries with the greatest antipathy to these horrors.

A review of Israeli Holocaust education indicates TLH has long been a compulsory part of the curriculum and pervades the education system:

“…the Holocaust is the only historical event which is taught throughout the curriculum from kindergarten to high-school. In teachers’ colleges courses about the Holocaust are obligatory and almost every student – not only history students – studies such a course. In the universities Holocaust courses have become very popular and very crowded, not to mention the many in-service training courses for teachers of all grades organized … by the Ministry of Education and other institutions.”

Not only is the Holocaust taught in classrooms, Israeli high school students are regularly taken on state-sponsored trips to Auschwitz and the sites of other death camps. Such excursions are not without controversy, as rather than encouraging somber reflection on universal values, they frequently turn into binges of Israeli ultra-nationalism. Jackie Feldman’s Above The Death Pits, Beneath The Flag: Youth Voyages To Poland And The Performance Of Israeli National Identity is an ethnographic study of these trips.

The impact in Israel is reported in Ha’aretz in 2016:

“Shulamit Aloni, then the education minister, expressed her repugnance for young Israelis who ‘march with unfurled flags, as if they’ve come to conquer Poland’. The death-camp pilgrimages, warned the former leader of the Israeli left, were creating a generation of xenophobes obsessed with the notion of Jewish might, but largely blind to the Holocaust’s universal lessons…

“Tel Aviv’s Gymnasia Herzliya, the oldest Hebrew high school in the country, became the first large public school to buck the trend, the nation took note. Citing the dangerous rise of nationalism in Israel, principal Zeev Degani announced that as of next year, Gymnasia Herzliya would no longer be sending delegations to Poland.”

The junkets to the death camps are particularly well satirized in Israeli novelist Yishai Sarid’s 2020 novel The Memory Monster written from the point of view of a historian from the Israeli Holocaust Museum Yad Vashem, who leads such tours. He channels a conversation by some of his teenage male students fueled by white supremacy that perversely turns from awe of the Nazis to hatred of Palestinians, left-wing compatriots, and even the millions of Jewish fatalities:

“…it’s hard for us to hate people like the Germans. Look at photos from the war. Let’s call a spade a spade: they [the Nazi soldiers] looked totally cool in those uniforms, on their bikes, at ease, like male models on billboards. We’ll never forgive the Arabs for the way they look, with their stubble and their brown pants that go wide at the bottom, their houses without whitewash and the open sewers on the streets, the kids with pink-eye. But that fair, clean European look makes you want to emulate [the Germans] …

“…On a tour of Auschwitz-Birkenau, this one fat student with mean eyes, cheeks purple with cold, began to scratch the words “Death to left-wingers” onto a wooden wall in the women’s camp. An alert teacher intervened and didn’t let him finish. His friends consoled him, promising to complete the work when they got back to Israel. They were cloaked with the national flag, wearing yarmulkes, walking among the sheds, filled with hatred – not for the murderers, but for the victims.”

In late 2023 and early 2024, we see Israel, presumably with soldiers just a little older than those fictional teenagers, conducting one of the most horrific bouts of sustained bloodshed since the Second World War. As of this writing, Israel had dropped 18,000 tons of bombs on Gaza, 1.5 times greater than the Hiroshima bomb. Even conservative estimates put the average number of Gazan civilians killed at 160 per day, (while the coalition against the Islamic State in Raqqa killed 20 civilians a day over four-months.) The nine-month battle in Mosul between Iraqi forces and IS killed less than 40 civilians a day. The rate of death of Gazan children has been about 140 per day compared to that in Ukraine during the Russian incursion (about 1 per day).

In their defence, Israel and its supporters insist that Israel was provoked by the Hamas 7 October attack where 695 Israeli civilians died, and Israel has the “right to defend itself.” Of course, all perpetrators of extreme violence claim provocation. And even if we accept that Israel has the right to defend itself, when does defence end and genocide begin?

Arguably, a consensus is emerging that the disproportionate killing in Gaza constitutes the crime of genocide, as set out in the 1948 UN convention enacted precisely because of the horrors of World War II. South Africa set out in its 84-page statement to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) a case that includes not only commission, but also intent. This is illustrated by a database of more than 500 statements from Israeli officials, like an army official at a morale-raising event exhorting, “Be triumphant and finish them off and don’t leave anyone behind. Erase the memory of them,” or Prime Minister Netanyahu invoking the biblical commandment that the Israelites utterly exterminate the nation of Amalek. Even former Israeli Supreme Court Chief Justice Aharon Barak, an ad hoc member of the panel of judges, joined the others in condemning this incitement.

South Africa’s case has been validated by the interim report of the ICJ.

So concerning were these statements of incitement by Israeli leaders that fifty Holocaust researchers at Jerusalem’s Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum (in January 2024) demanded that the museum’s director condemn such provocation.

“We, the undersigned, know from Jewish and human history, especially from studying the Holocaust and its memory, that incitement to extermination and to commission of grave crimes, using language that creates dehumanization and an incrimination of all members of a rival group within a conflict, are in many cases a first step in committing crimes that can reach the stage of genocide.”

A trump card wielded by Israel and its supporters is that all comparisons of Israel’s wars and occupations to the Holocaust are bogus because they do not match in every detail. Unlike the Nazis, for example, they maintain, Israel is not herding innocent civilians into gas chambers. And this despite the intensity of the Gaza killing, the sheer numbers in killings, starvation, demolition pale in comparison with those of the Holocaust. In fact, argues the counter-claim, the Holocaust is unique in history, indeed outside of history, and all comparisons to it are spurious.

And then, the kicker: the accusation that anyone who would use the Holocaust to make comparisons, especially against Israel, is ipso facto antisemitic.

Can Life Lessons Be Drawn?

But this introduces another dilemma and contradiction. On the one hand, the ostensible reason for insisting that the Holocaust be taught is that students can draw life lessons from it, i.e., that it is a “teachable moment.” A “teachable moment” can be defined as “a specific occurrence, situation, or experience that can be used to teach people about something more general.” Implicit in the notion of “teachable” is that the specific circumstance being used is comparable to the conditions of the students’ lives. Presumably, the more comparable, the more learning can occur.

However, a confounding question arising in such discussions is “how comparable is the Holocaust?” The influential group who advocates that the “Holocaust is outside of history” is caught squarely on the horns of this dilemma.

A particularly revealing example presented itself in June 2019 when a group of US politicians, including Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, denounced cantonments for Southern migrants at the US border as “concentration camps.” Almost immediately, an overwhelming chorus of critics weighed in, insisting the term was inappropriate and insulting to the memory of the Holocaust. No matter that even the Nazis themselves did not invent the term “concentration camp.” (It was rather the Americans in the war against Spain and the British in the Boer War who thus described their mass internment, under horrific conditions, of civilians.)

Soon, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum itself published a statement, announcing that it “unequivocally rejects efforts to create analogies between the Holocaust and other events, whether historical or contemporary,” and that “the Museum further reiterates that a statement ascribed to a Museum staff historian regarding recent attempts to analogize the situation on the United States southern border to concentration camps in Europe during the 1930s and 1940s does not reflect the position of the Museum.”

However, the Museum’s statement was quickly rebuked by a statement signed by 375 top Holocaust and other scholars, including Omer Bartov, Doris Bergen, Andrea Orzoff, Timothy Snyder, and Anika Walke, who argued precisely the opposite, that the museum was

“…taking a radical position that is far removed from mainstream scholarship on the Holocaust and genocide, …

“…and it makes learning from the past almost impossible.

“[The real value of Holocaust education] is to alert the public to dangerous developments that facilitate human rights violations and pain and suffering, as identifying similar events is a fundamental part of this effort.”

Just such a recent controversy has famously embroiled Russian-American writer Masha Gessen. Gessen was awarded the Hannah Arendt Prize by the Heinrich Böll Foundation (allied to the German Green Party) for their iconoclastic journalism (Gessen prefers non-gender-specific pronouns). But the Foundation forswore its support because of a Gessen-penned New Yorker article that compared the current destruction of Gaza by Israeli forces to the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto by the Nazis. Critics found the following passage particularly offensive:

“…comparing the predicament of besieged Gazans to that of ghettoized Jews… also would have given us the language to describe what is happening in Gaza now. The ghetto is being liquidated.”

The irony of the Foundation’s baulking on a prize named for so prominent a nonconformist and critic of Israel as Arendt was so thick that Gessen themself cut it with a knife so eloquently in an interview with Amy Goodman on Democracy Now. Said Gessen (emphasis added):

“My argument is that in order to learn from history, we have to compare. Like, that actually has to be a constant exercise. We are not better people or smarter people or more educated people than the people who lived 90 years ago. The only thing that makes us different from those people is that in their imagination the Holocaust didn’t yet exist and in ours it does. We know that it’s possible. And the way to prevent it is to be vigilant, in the way that Hannah Arendt, in fact, and other Jewish thinkers who survived the Holocaust were vigilant and were – there was an entire conversation, especially in the first two decades after World War II, in which they really talked about how to recognize the signs of sliding into the darkness.”

Indeed, an observer joked in The Guardian that “Hannah Arendt would not qualify for the Hannah Arendt prize in Germany today.”

Holocaust Education and Racialized Peoples

It is one thing to ask how effective teaching and learning about the Holocaust is for white students of European background. We still assume that this white demographic is normative. But countries like Canada, the US, and in Europe have had a significant population of non-white, non-Europeans for many years. At least one quarter of Canadians are in this category, with a similar proportion in the US. Accordingly, the question of Holocaust education should take on a very different tone.

Esther Romeyn of the University of Florida explores the impact of Holocaust memorialization using the multi-racial Netherlands as her canvas and sums the dilemma up this way:

“Deployed as guarantee of European postwar liberal ‘tolerance’, European Holocaust memorialization tends to figure the Shoah redemptively, as an object lesson in ‘intolerance’ demanding anti-racist vigilance and the protection of Jews and other minority groups from discrimination. Increasingly, however, I will argue, this conjuring of the ghosts of Jews and the Holocaust serves as a nationalist and racist conceit, designed to drive a wedge between a redeemed, post-racial Europe supposedly pledged to racial, gender, and sexual equality, and Europe’s disenfranchised immigrant, minority and Muslim populations. This instrumentalization of Holocaust memory not only implies what Alvin Rosenfeld has criticized as the transformation of the horrors of the Shoah into a universalist moral ‘uplift’ story of an ongoing fight of the human ‘spirit’ against intolerance.”

In other words, the Dutch authorities employ the memory of the Holocaust and antisemitism to help promote good “European” citizenship for its newer Brown and Muslim arrivals. How smug and arrogant to take non-white people, some of them refugees, who may have had descendants and relatives massacred in colonial and neo-colonial wars, and tell them that the worst example of racism and brutality, the one to especially commemorate, is a genocide of Europeans by Europeans, conveniently omitting that the Nazis took their ethnic cleansing lessons from those of other European powers dominating the Third World, and their own colonial history in what is now Namibia.

Romeyn calls this “the reframing of tolerance as a ‘civilizational discourse’ or part of a white European “civilizing mission.” This has recently taken on ominous tones as far-right politician Geert Wilders captured a majority of seats in the Dutch November 2023 legislative election. Wilders is on record as claiming that Palestinians should all move to Jordan. Even as non-white Dutch citizens are cautioned to commemorate the Holocaust, their government supports Israel’s slaughter in Gaza.

One of the criticisms of social studies and literature curricula in North American and European countries is that it is too Eurocentric. As schools attempt to rectify this lapse, proponents of Holocaust education worry that it will receive less emphasis.

This insistence on universal due homage to the Holocaust and antisemitism exacerbates tensions between the Black and Jewish communities, especially given the genocide of the Transatlantic slave trade and three hundred plus years of bondage in the Americas. I have pointed out elsewhere how the “[r]acialized are prime targets of pro-Israel attacks – and it’s deliberate.”

“What do Faisal Bhaba, Desmond Cole, Javier Dávila, Nadia Shoufani, Rehab Nazzal, Rana Zaman, Linda Sarsour, Idris Elbakri and Fadi Ennab and countless others have in common?

“They are racialized people who have been special targets of pro-Israel lobby organizations in Canada because they spoke out on Palestinian rights. And these examples suggest how the defend-Israel-at-all-costs industry has a racism and Islamophobia problem.”

To underscore fraught relations between the Black and Jewish communities, we may cast our minds back to the controversy and international ‘scandal’ that emerged in 1994 when a group of Black and Latino students were ejected from an Oakland, California movie theatre for laughing during a scene in Schindler’s List. They had not been given any preparation for the harrowing film. Accusations of Black insensitivity to Jewish suffering were liberally and unfairly disseminated.

Recently, South Asian-origin journalist Shree Paradkar lost part of her position at the Toronto Star for her criticism of Israel. Afro-American journalist Marc Lamont Hill lost a job at CNN for a similar offence. More recently, and most spectacularly, Claudine Gay, the first Black president of Harvard University, was forced to resign that position when what precipitated her fall from grace was her avoidance of an unfairly loaded question from a US congressional committee. Such takedowns will not easily be forgotten by non-white people, and likely, more widely.

Moreover, two movements, Critical Race Theory (CRT) and Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI), have both come under fire from Jewish establishment organizations. Both CRT and EDI insist that race is a crucial fault line in white European settler societies, historically, and going forward. The Jewish organizations insist that their community is not only left out of these initiatives, but as summarized by Russel A. Shalev:

“Critical Race Theory (CRT) and Intersectionality understand society as comprised of overlapping and interconnected levels of racial oppression. Critical Race Theory simplistically erases the uniqueness of the Jewish experience and identifies Jews as ‘white’, CRT’s oppressor class.”

At best, Jewish groups merely feel aggrieved at their inclusion as white and privileged and at their virtual exclusion from the club of racism’s victims. At worst, they join the radical right’s opponents of CRT and EDI in attempting to discredit these initiatives.

Jews are especially ambivalent toward these latest trends in anti-racism. On the one hand, Jews tend disproportionately to favour civil rights and liberal causes, mainly because of their long history of oppression. On the other hand, Jews have been disproportionately successful in North America, and are wary of any theory that ascribes life chances to skin color and are distrustful of official attempts to redress historic racial imbalance by affirmative action based on historic disadvantage and proportion in the population. As psychologist Pamela Paresky, in an essay that otherwise condemns CRT and EDI initiatives, puts it,

“This obviously presents a particular problem for Jews, who represent roughly 2 percent of the US population. A much higher proportion of Jews than non-Jews attend college. Jews represent an outsize share of winners of major awards, like Nobel prizes. As of 2020, seven of the 20 wealthiest Americans were Jewish. In virtually every major American industry and institution, Jews hold leadership roles disproportionate to their overall demographic numbers.”

Many Jews, in short, enjoy no small degree of privilege in North America and Western Europe. They are, understandably, reluctant to surrender that privilege. But they want to be acknowledged as victims as well. The co-existence of privilege and prejudice is quite normal. But it presents a tension that is very disruptive for the Jewish community and poisonous to its relation with the rest of society.

The Weaponization of the Holocaust

For the past half-century, especially since the 1967 Six-Day War, despite the chorus insisting antisemitism is running amok, Jews in North America and Western Europe have experienced the exact opposite: an almost unprecedented degree of acceptance, nay, admiration from their fellow citizens.

Israeli scholar Ran HaCohen went so far as to conclude, in 2003:

“It is high time to say it out loud: in the entire course of Jewish history, since the Babylonian Exile in the 6th century BC, there has never been an era blessed with less antisemitism than ours. There has never been a better time for Jews to live in than our own…”

Canada is no exception, and in fact, may be one of the most philo-semitic places in the world. The American Anti-Defamation League’s international survey puts Canada for years – as one of the least antisemitic countries in the world.

Bernie Farber, former CEO of the Canadian Jewish Congress and former head of the Canadian Anti-Hate Network, suggests (2015):

“We have come to a point in the 21st Century where at least in the halls of government and I think very much in the mainstream of Canadian life, we are viewed as part and parcel of Canadian polity.”

York University Jewish Studies scholar David Koffman insists:

“Canada may now very well be the safest, most socially welcoming, economically secure, and possibly most religiously tolerant home for the Jews than any other diaspora country, past or present.”

Most Canadians are smart enough to know the difference between Jews and Israel, and continue the love affair with Jews even as Israel carries on as a genocidal rogue state. At least for now.

Yes, antisemitism has been on the rise for several years, but it is rising not independently, but commensurate with a rise in North American and global white nationalism that targets many in addition to Jews. And Israel’s Gaza war has sparked antagonisms which too many Jews want to interpret as antisemitism.

In fact, so popular have Jews been in Canada in the past fifty years that I would put forward a very different interpretation of recent events. Most Canadian Jews have become used to basking in the consistent veneration and respect they have received as Jews. But for many Canadian Jews, blinkered by their allegiance to Israel, rising criticism of that country’s behaviour is seen as a slap in the face to themselves, as Jews. And those Jews and their collective institutions express their sense of betrayal by lashing out with accusations of…antisemitism.

One suspects that the current insistence that Holocaust education be compulsory is part of a phenomenon whereby accusations of antisemitism are weaponized to silence points of view disliked by the institutional Jewish organizations.

Why accusations of antisemitism are especially powerful is well described by Stephen Beller:

“… [Accusations of antisemitism are] rhetorically very powerful because as soon as you label someone antisemitic you can dismiss them and their arguments as irrational, as insane, and hence they do not have to be taken seriously, or alternatively have to be taken extremely seriously as a threat not only to Jews but to the whole of society and humanity. It can serve as a political “magic wand,” like calling someone a “racist,” “sexist,” “fascist,” etc., or a “socialist” in other quarters. Yet, antisemitism is more powerful than almost any of these because of its association with the Holocaust…

“…If you call someone an antisemite you are in effect associating them with the Holocaust – that is the nuclear option of political rhetoric.” [emphasis added]

But the use of the accusation of antisemitism in debate is one thing. How much more powerful if its use can be built in to a formal definition of antisemitism, a definition that is widely accepted and included in the standards of ethical behaviour of legislatures, municipal councils, school and university boards, and police forces, a trap that automatically snaps shut on critics of Israel without debate!

The weaponization of accusations of antisemitism is epitomized by the so-called International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance – Working Definition of Antisemitism (IHRA-WDA). As is now well-known, while its preamble is vague and anodyne, the devil lies in the details, i.e., a list of eleven examples, seven of which refer to criticism of the State of Israel. Jewish institutional organizations like CIJA, B’nai Brith Canada, and Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Centre are touting the IHRA-WDA as the gold standard definition.

There are several alternative definitions, like the 2021 Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism, convened by the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute and endorsed by around 300 scholars in antisemitism, the Holocaust, and Jewish Studies around the world. But the IHRA-WDA has had a head start of almost twenty years. A petition of over 600 Canadian and over 200 Jewish-Canadian scholars, motions by over forty academic unions, and a unanimous resolution by the Canadian Association of University teachers have called the IHRA-WDA a violation of academic freedom. Nonetheless, the IHRA-WDA has proven popular, not so much due to its acuity or accuracy but rather as it offers a kind of moral prophylactic for governments and organizations to prove they are not antisemitic.

Proponents of the IHRA-WDA insist that it is non-legal and non-punitive, but in fact, aspirational: meant simply to educate. But its use in practice shows that it is anything but benign. The use of the definition to punish ostensible offenders around the world has been well-documented. This author has written about a 2018 public meeting at the University of Winnipeg marking the Trump administration’s move of the US Embassy from Tel-Aviv to Jerusalem. Nothing about the meeting was antisemitic and even the criticism of Israel there was mild. Yet, after a complaint by B’nai Brith Canada, the university, employing the IHRA-WDA, deemed the meeting antisemitic. The organizers were punished by refusal of future venues at the university.

Due to its overuse, and Israel’s recent horrors in Gaza, the accusation of antisemitism may be wearing thinner. But it still packs a punch, boosted by the IHRA-WDA.

What ‘Compulsory’ Really Means

And that leads us back to the question of why the recent emphasis on the word ‘compulsory’ regarding Holocaust education.

Let us be clear. If a subject is on the educational curriculum, and the content is specified, it is compulsory. It means that teachers must teach the material and cannot choose to ignore or skip it.

For example, as mentioned above, in Ontario, when the grade 11/12 curriculum prescribes the following topics: “The Nazi Revolution,” “Why Hitler? Why Germany?” “The moral problems of the Nazi regime as embodied in the Holocaust,” “An analysis of the rationalization of evil. Is anyone innocent?” and “Demonstrate an understanding of the key factors that have led to conflict and war…and genocides, including the Holocaust” it means that teachers must cover these topics.

Or, as mentioned above, in British Columbia, the Grade 12 social studies curriculum explicitly includes the Holocaust and anti-Jewish pogroms. But not every single student in BC will take that course. The newly-initiated curriculum will include the Holocaust and other genocides in Social Studies 10.

If teachers are required to teach the Holocaust, then why the demand for it to be “mandatory”?

There are two possible reasons for this new demand:

- Teachers are refusing to teach the prescribed Holocaust curriculum which is very dubious, or

- Despite the curriculum, messages and lessons from the Holocaust aren’t getting through to students.

As for reason #1, there is no evidence of a mass rebellion by teachers against the Holocaust curriculum. Indeed, it is hard to believe that social studies and history teachers are anything less than enthusiastic about teaching the Holocaust. It is also hard to believe that students don’t find it interesting.

As for reason #2, we know from the above-cited studies that accurately measuring the impact of Holocaust education is difficult. We also know that there is a problem agreeing what precise outcomes Holocaust education is meant to produce, much less measure those outcomes.

Even if we believe the statistics cited in the Liberation 75 report about poor high school student knowledge of the Holocaust, there are several possible causes for that other than the quality of Holocaust education in our schools.

For example, as we move away in time from the Holocaust, it is natural that its presence in the mind of young students is waning. Also, fewer survivors and others with a living memory of those events are alive. There are still plenty of popular references to the Nazi regime and to Hitler in popular culture, movies, and television series. But it is hard for anyone, much less young people, to believe that modern so-called “bad guys” like Vladimir Putin, or Bashar al-Assad, or Mouammar Khaddafi, or even Hamas (whose one-day rampage killed 766 civilians, both Israeli and foreign) are comparable to what they are taught in school, watch in movies, TV and web, and read about the Hitler regime.

There is, however, one possible lesson from the Holocaust that some Jewish institutional organizations feel is not being learned well enough, and which helps explain the current panic about Holocaust education. The lesson is especially relevant as Israel slowly over several decades, and then recently very quickly, has taken on the status of an apartheid and then a pariah state, and it now stands accused of the crime of genocide before an international tribunal.

The lesson that Jewish institutional organizations want learned, expressed in clear and brutal language, can be summarized thus:

“A third of the Jewish people alive in the world at the time were slaughtered in the Holocaust, an atrocity worse than any other committed against a people in the history of the world. Israel is now the state of the Jewish people, a state whose very existence came about because of, and is supposed to be an antidote to, that slaughter. In light of the Holocaust, whatever Israel does to defend itself, especially against the resistance of the Palestinians, is permissible, even if it appears to violate or actually violates norms proscribed by international law after World War II, and even if it violates accepted standards of human rights. Those who oppose Israel’s right to violate these norms or refuse to cut Israel some slack are antisemites.”

This message does not have to be explicitly stated in order to be understood. Indeed, the idea of giving Israel a free pass does not need to be said out loud. The immensity of the horror of the Holocaust almost automatically makes most caring human beings wish to help prevent anything like it recurring. This naturally contributes to upping our tolerance to arguments outside of our Holocaust training that Israel is merely defending itself or to have doubts that Israel could really be committing anything close to a genocide. This is especially useful as the death toll in Gaza mounts daily.

Moreover, if the accusation of antisemitism is not enough to deter critics of Israel, or supporters of Palestinian emancipation, or even petition-signers, then the fallback strategy is a campaign of calling out, cancelling, shutting down, firing, suspending, doxing, in short a campaign of civil terror. To name only a few examples among many in Canada since 7 October:

- Based on a complaint by a colleague who disagreed with him, University of Ottawa suspended a 4th year medical resident after the latter posted pro-Palestinian comments on his personal social media.

- CTV fired a Palestinian employee in Halifax who had organized rallies critical of the bombing of Gaza in her non-work time.

- Global TV in Toronto fired a Palestinian journalist for posts she made in her private social media.

- George Brown College in Toronto suspended a culinary instructor, for posting “Palestine Will Be Free” on a private social media account.

- On a closed Facebook group called Canadian Jewish Physicians, several posts suggested reporting healthcare colleagues who had signed a petition about health care in Gaza in the wake of the Israeli incursion to their superiors.

- A Toronto franchise of the restaurant chain Moxies, responding to public complaints, fired several employees for applauding as a march in support of Gaza passed by.

It’s not really about antisemitism at all; it’s all about Israel. That is the lesson that Jewish institutional organizations fear might not be getting through.

So when we hear that Holocaust education must be ‘compulsory’ we can be assured that proponents know that is already generally compulsory. What they find wanting is the teaching. What they mean by ‘compulsory’ is not that it be taught in schools. It already is taught in Canadian schools. The problem is that teachers have too much leeway in how they teach the Holocaust. The problem is that the Holocaust education often comes bundled with other genocides which, in the eyes of the institutional Jewish organizations, diminishes the Holocaust.

By ‘compulsory’ the Jewish institutional organizations mean that they want to have greater control over how it is taught. And this control can be achieved in two ways: either specifying precisely, or as closely as possible, the content that teachers must follow. Or, better yet, teaching it themselves.

We know that Jewish institutional organizations, especially the Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Center (FSWC), already do both. They prescribe content of curriculum and, in some cases, they go into schools and teach about the Holocaust and antisemitism. In its 26 January, 2024 newsletter, FSWC claims to have “taught more than 153 student workshops in 22 school boards to nearly 5,000 students in November, 2023 alone.”

How do we know that what is outlined above is what they really want learned in schools?

We can point out what can happen when they do directly teach the Holocaust. In late December 2023, the CBC reported thus:

“Two employees at the Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Center (FSWC) for Holocaust Studies – a Toronto-based non-profit human rights organization dedicated to Holocaust and antisemitism education – told CBC News that the centre’s educators who teach workshops and courses in schools have been instructed to report students who make comments critical of Israel to the organization.

“CBC has agreed to keep the employees’ names confidential because of a potential risk to their employment.

“Comments or questions referencing genocide or occupation of Palestinian people and ‘anything seen as critical of Israel at all’ are to be reported to the organization, said one of the employees.

“‘The idea is to contact the school, inform the school they have an antisemitism problem and pressure the school to shut down the Palestinian support [by] accusing them of antisemitism, encouraging more pro-Zionist workshops or lessons,’ they said.

“Both employees said these directives were communicated by centre leadership verbally during meetings with the organization’s director of education and sometimes the CEO but were not written down.

“‘They push for us to understand the stance of the organization, which is being pro-Israel,’ said the second employee. ‘If you’re not pro-Israel, then you’re antisemitic’.”

In other words, according to the whistleblower, when FSWC is given access to high school students, one of its tasks, beyond mere teaching of the Holocaust, is surveilling and fingering students who dare to criticize Israel, even as the death toll in Gaza rises.

A group of over twenty organizations, including Independent Jewish Voices, the Palestinian Canadian Congress, the United Jewish People’s Order, Showing Up for Racial Justice, and Toronto Jewish Parents, have written to school boards and relevant ministers across Ontario informing them of these incidents and demanding a formal investigation into not only this particular instance of vigilantism but also the whole question of FSWC’s access to students. The letter asks the recipients:

“There can be no doubt that the targeting of students for their political views is a violation of their civil rights and must not be tolerated. Indeed, the Toronto District School Board stipulates in Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Policy PO94 that it is forbidden to disclose personal information about a student including ‘the personal opinions or views of the individual except if they relate to another individual.’ The policy goes on to state that ‘You must have the authority to collect the information, usually from a statute such as the Education Act, Section 265, which provides the authority for the collection of information for the pupil record or OSR’.”

In summary, then, the goal of the demand for ‘compulsory’ Holocaust education has little or nothing to do with promoting anti-racism or even combatting antisemitism. It is about defending Israel, proscribing critics, curtailing freedom of expression and convincing schools that they need to hand over even more of their curriculum to pro-Israel organizations. •