Obstacles to Palestinian-Israeli Peace

If Al-Qaeda and ISIS were the indirect products of the policies of US imperialism, Hamas is a direct product of Israel. A glimpse into the painful history of 75 years of conflicts and confrontations between Israel and Palestinians helps one better understand the latest Hamas/Israeli fighting that started on October 7, 2023.

The Origins of the Palestinian Movement

Prior to the establishment of the state of Israel, Palestinians were overpowered from two sides: the British, and militant Zionist groups. Following the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, about 700 thousand Palestinians were displaced and sought refuge in the West Bank and Gaza, and in neighbouring countries. They formed several organizations in exile, most notably the Arab National Movement (ANM) in 1951, emphasizing Arab unity, secularism, socialism and later Marxism. Influenced by the Baathist and later Nasserist Arab nationalisms, ANM went through several phases and splits, eventually focusing solely on Palestine, establishing the National Front for the Liberation of Palestine (NFLP). Internal strife led to more splits, including the creation of the Popular Front (PFLP) led by George Habash, and the Democratic Front (PDFLP) led by Nayef Hawatimah. These organizations and their subsequent offshoots, as well as Fatah, formed by Yasser Arafat in 1959, and eventually the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1965, were largely secular, nationalist, and some socialist and Marxist, though, of course, they also had religious elements among them.

Early Palestinian organizations were weakened for reasons other than their conflicts with Israel. Initially, they came under the influence of Baathist nationalism, which led to splits and rivalries in the Syrian and Iraqi sectors. Then, with the growing influence of Gamal Abdel Nasser, especially after his so-called victory in the Suez War of 1956, they were largely influenced and controlled by Nasserism. Many received military training in Egypt, but up until the 1967 June war, while Nasser was preparing his army for war with Israel, he prevented the Palestinian combatants from engaging with the Israeli army before the Egyptian army was fully prepared. Following the defeat of the Arab armies, the Palestinian movement followed in the footsteps of the Algerian liberation movement, and to some extent their Yemeni counterpart, and tried to act independently.

Following the humiliating defeat of Arab armies in 1967 and the Israeli occupation of the West Bank/East Jerusalem, Gaza, Sinai, and the Golan Heights, Israel’s main preoccupation was curtailing Palestinian guerrilla attacks and incursions on Israel’s new frontiers. The war led to some three hundred thousand new refugees fleeing to neighbouring countries. In 1970, King Hussein of Jordan, frustrated with the increased activities and interventions of Palestinian organizations in Jordanian affairs, carried out a large-scale massacre and forced many to seek refuge in Syria and Lebanon. The PLO headquarters moved to Lebanon. In 1972, the ultra-militant Black September group that had emerged from the conflicts between Jordan and the PLO took Israeli athletes hostage during the Munich Olympics, leading to the deaths of all the hostages and the hostage takers.

By the early 1970s, parts of the Palestinian movement including Fatah, which through its armed wing Al-Asifa had organized the first guerrilla attacks inside Israel in 1964, had reached the conclusion that the military defeat of Israel was not possible, and they had to find alternative ways to achieve their goal, including on the public relations front, which saw the opening of offices in European countries. Starting in 1972, Mossad, concerned about this Palestinian initiative, and angered by the massacre of the Israeli athletes and other guerrilla actions, resorted to assassinations of prominent Palestinian figures, among them intellectuals, artists, professors, and jurists in Europe, many of whom were, ironically, supporters of peaceful resolutions; notable amongst them were the poet and journalist Ghassan Kanafani; poet Wail Zweiter; economist Mahmoud Hamshahri, who was Fatah’s representative in Paris; law professor Basil Al-Kubaissi; and poet Kamal Nasser.

The 1973 October war brought many changes to the region including international efforts to forge peace between Arab states and Israel, and finding a way to attend to the Palestinian cause. 1974 saw a suspected split of the Fatah organization, the Fatah Revolutionary Command led by Abu Nidal, a terrorist organization that violently killed or injured hundreds of civilians in different countries. It also assassinated several prominent Palestinian leaders, and since it carried the name Fatah, it caused a great deal of damage to the efforts of Fatah aimed at improving international perceptions of the Palestinian movement. When, in 1982, Ariel Sharon was preparing to invade Lebanon to expel Palestinians, the Abu Nidal group attempted to assassinate the Israeli ambassador in London; even though Mossad presumably knew full well that Nidal had nothing to do with Arafat’s Fatah, the Israeli army invaded Lebanon and through massive bombardments forced the PLO to once again change its base, this time out of the immediate region, into Tunisia.

The Arrival of the Islamists

In 1973, Sheikh Ahmad Yassin, a fundamentalist Islamic cleric – himself a Palestinian refugee in Gaza who had been expelled along with his family at the age of 12 and had received some education at Egypt’s Al-Azhar University – formed a charity called Mujama al-Islamiya. His objective was to spread his obscurantist religious views in the poverty-stricken and overcrowded Gaza Strip. As he gained followers, he also garnered support from the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and was able to establish new mosques. The group launched sporadic attacks on secular and progressive Palestinians, burned down cinemas, murdered sex workers, and forced hijab on women in their neighbourhoods. With greater influence, they took over the Islamic University of Gaza and fired secular progressive faculty and students.

Israel, which had had full control of Gaza since 1967, was being continuously hit hard by secular forces and decided to fuel internal conflicts among the Palestinians by strengthening the Islamists and helping Sheikh Yassin’s “charity”, formally recognizing it in 1979.

In 1981, another Islamist group, the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, a split from Egyptian Jihad (which had assassinated Anwar Sadat) and encouraged by the emergence of the Islamic republic in Iran, called for the establishment of an Islamic state in Palestine on the pre-1948 borders. In 1984, Israel learned that Sheikh Yassin’s supporters were hiding weapons in mosques and arrested him, although he was later released through a prisoner exchange. Since then, conflicts between the Palestinian Islamists and Israel have only intensified.

At the inception of the first Intifada in 1987, Sheikh Yassin and Abdelaziz Rantissi, a fundamentalist physician and a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, created the Islamic Resistance Organization, HAMAS, with the aim of establishing an Islamic state in Palestine. During the first Intifada (1987-1993), in the absence of the PLO, which had been expelled from the region, Hamas quickly gained influence and created its military wing, the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigade. As peace talks between Israel and Palestine began in the early 1990s and led to the Oslo Accords, Hamas opposed and confronted the PLO on the subject, and to make matters worse, parts of the Palestinian left, including the influential Popular Front, who were also against the peace talks, collaborated with Hamas.

In 2004, Sheikh Yassin was assassinated by Israel, and Rantissi succeeded him, though he would be killed a month later. However, Hamas survived the loss of its founding leaders and grew in popularity, expanding its social influence, building new mosques (there were 1,080 mosques in Gaza before the current war), and starting to dominate different aspects of Gazan society, including in universities and colleges, silencing and expelling non-believer faculty and students.

Concerned about the monster that it and its allies had created, Israel unilaterally decided to evacuate Jewish settlements in Gaza in 2005, moving them to the West Bank, and totally encircling the Strip by land, air, and sea, turning it into the largest prison in the world.

In the 2006 Palestinian Legislative Council elections, Hamas gained more seats than the PLO and formed a joint government. Israel refused to recognize the results. The internal divisions eventually led Hamas to engage in a coup d’état against the PLO, and since 2007, it has ruled the Gaza Strip. At the same time, Israel, claiming that the UN relief agency for refugees, UNRWA, was under the influence of Hamas, pushed the United States, Canada, and some other allies to cut funding. This misguided policy significantly helped Hamas, as Gazans became more radicalized and dependent on Hamas’ charitable services.

Hamas, despite its anti-Shia ideology, got closer to Hezbollah in Lebanon, found a base there and gained the support of the Islamic regime in Iran. With the beginning of the Syrian civil war, however, Hamas, unlike Islamic Jihad, which had closer relations with Hezbollah and the Iranian regime, refused to support the Assad forces and was expelled from Lebanon. But with the continuation of the conflicts in Syria, Hamas’s relations and support from Iran improved, and it was able to reestablish its bases in Lebanon.

With the Palestinian movement divided into two separate entities – the turbulent and chaotic Gaza under Hamas rule and the relatively tame West Bank under the Palestinian Authority (PA) – Israel adopted a dual policy, which I have discussed elsewhere. While forcefully reacting to Hamas incursions and rockets and heavily bombing Gaza in successive wars of 2008-09, 2012, 2014, and beyond, Israel used Hamas as an excuse to advance its own overall expansionist policies towards Palestinians. In the West Bank, it supported Palestinian “self-government,” which acted as a sort of colonial state run by local rulers; out of about 155,000 PA employees, about 60,000 are in security and policing. In the West Bank also, Israel facilitated the expansion of Palestinian cities like Ramallah, where the new middle classes working in government and in a wide range of foreign-funded NGOs have found relatively prosperous lives, and despite dissatisfaction with Israeli occupation, are not willing to risk their newly-gained status. The working class, working in small and medium industries and construction, live and work in insecure economic conditions, as do the farmers and traditional middle classes. While Israel continues its expansion of illegal Jewish settlements, the most bitter irony is seeing long lines of Palestinian workers at the entrances of these settlements, looking for work on construction sites or on settlers’ farms.

Aside from Palestinian religious organizations, there have also been other Islamist groups that have been drawn into the Palestinian/Israeli conflicts. Two of these are based in Lebanon. One is Amal, originally formed in 1974 in response to the plight of the country’s Shia minority and coming into conflict with Israel after the latter’s first major invasion of Lebanon in 1978. The other is the Lebanese Hezbollah, formed with the help of the Islamic regime of Iran after Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, and which fought a war with Israel in 2006.

In short, along this long path, the Palestinian movement was severely weakened. With the growing strength of Jewish fundamentalists and right-wing political currents and the growing weaknesses of both the left and liberal forces in Israel and among Palestinians, the “Palestinian question” appeared to be fading, to such an extent that the Trump administration initiated the Abraham Accords, hoping to bring all Arab autocracies and Israel together. However, the October 2023 Hamas attack and Israel’s response has once again attracted the world’s attention to the unresolved Palestinian problems.

The Accumulated and Unresolved Problems

The main problems following the establishment of the State of Israel can be grouped into several categories, none of which were ever seriously dealt with in the numerous “peace” negotiations.

Displacements and Refugees

During the first war (1947-49), about 700,000 of Palestinians living in Palestine were displaced and sought refuge in the West Bank, Gaza, and neighbouring countries of Jordan, Syria, Egypt, and Iraq; more than 400 Palestinian villages and cities were evacuated at the time. Meanwhile, an increasing number of Jews arrived in Israel from Europe, Asia, and Africa. The UN created UNRWA to take care of Palestinian refugees, and General Assembly Resolution 194 called for their conditional right of return. In the subsequent wars, especially in 1967 and 1973, hundreds of thousands more were added to the refugee populations.

Today more than 5.5 million Palestinians are registered with the UN. About 1.5 million of them live in UNRWA refugee camps, under very difficult conditions; some of the camps house more than 100,000 people in extremely limited spaces. In Jordan, which has the largest number of refugees, many have obtained Jordanian citizenship. In Syria and particularly in Lebanon, however, the refugees live under dreadful conditions and are banned from many professions.

Borders, the Walls, blockades and checkpoints

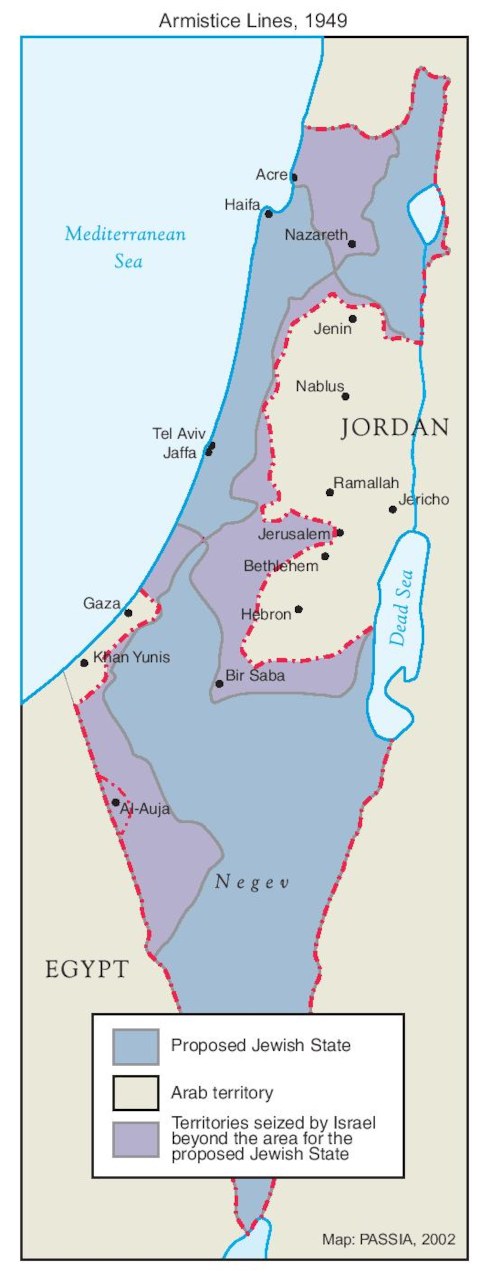

After the defeat of the Arab Armies, the Rhodes Armistice Line of 1949, also known as the Green Line, was agreed upon by Israel and the neighboring Arab states, establishing the armistice line (not the permanent borders of Israel). The armistice agreements established three demilitarized zones near the Jordan River and the Sea of Galilee, but eventually, Israel took these over.

Following Israeli conquests in the June 1967 war, Israel started to build Jewish settlements in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, prohibited by the Fourth Geneva Convention and Security Council Resolution 452. Currently, over 200 settlements and outposts house over half a million settlers, all of them illegal under international law. Twelve settlements were also created in East Jerusalem within the heart of the Old City, next to the majority Palestinian population. In Hebron (Al-Khalil), an officially Palestinian city under the Oslo Accords with a population of about 240,000, live several hundred fundamentalist Jewish settlers, protected by 1,200 IDF soldiers. Some of these settlers reside above the town’s marketplace and frequently throw stones, bricks, and rubbish on the metal gratings that cover the market beneath. Many shops in the market have, in fact, had to close or go out of business altogether.

In 2002, Israel decided to build a massive concrete wall separating the West Bank and Israel, but actually placing much of the wall within the West Bank, in some areas penetrating more than 15 miles into the occupied territory. It also created large settlement complexes around East Jerusalem, effectively separating it from the West Bank.

The Oslo Accords, as will be discussed shortly, divided the Occupied Territories into three zones: Area A, consisting of seven Palestinian cities; Area B, under Palestinian administration with joint Israeli-Palestinian security; and Area C, under Israeli control and security. The Israel security zone covers the settlement blocs plus the whole border of the Jordan River and the Dead Sea. This is just a pretext to control the rich and fertile Jordan valley and access to the river; in the past several decades, thanks to Jordan’s cooperation with Israel, not a single guerrilla incursion has been reported from those borders. It is reasonable to assume that if the Palestinian Authority had control over the valley, it would have been much less dependent on foreign aid and borrowing. The Dead Sea, which is dying as a result of overuse of the Jordan River’s water, is very rich with various minerals that are used by Israel’s cosmetic companies that enjoy monopolistic control over the Sea’s west side. Palestinians are deprived of access to the Sea. I heard from the governor of Jericho (Eriha), whose city and region are close to the Dead Sea, that he has never been allowed to go to the shore of the Sea.

All major roads and highways are also under Israeli control, and hundreds of miles of highways are solely for the use of Israeli citizens and not accessible to Palestinians. In addition, hundreds of military checkpoints on common roads control the flow of cars and pedestrians, which sometimes take hours to pass through.

Maritime borders, fishing and access to natural gas reserves

The Oslo Accords set the maritime border of the Gaza Strip with the Mediterranean twenty nautical miles from shore, except for the two northern and southern shores where Jewish settlements were located at that time, and in which Gazans were prohibited from fishing. Although this borderline limited Gazan fishing access, it was enough for local consumption. With the beginning of the second Intifada, in 2000, Israel severely restricted Gazan access to the sea. Under international pressure this border was set to twelve nautical miles. In 2006, with the success of Hamas in the Palestinian National Council elections, Israel reduced this border to six nautical miles, and at times, reduced it further to three miles. The immediate effect of these restrictions was to deprive Gazans from making a meagre living from fishing and eliminated a major food source for the impoverished population of the Strip. Israeli bombing of Gaza’s sewage treatment plant, sending sewage into the sea, further disrupted Gaza’s fishing.

More importantly, with the discovery of a massive natural gas field in 2000 within the Oslo-set Gazan maritime border, Palestinians could have access to a major source of revenue. A 25-year contract was signed between the Palestinian Authority, British Gas, and a Lebanese-owned company. Israel, particularly when Ariel Sharon formed his government in 2001, had no intention of allowing Palestinians access to this income and blocked the implementation of the contract; Hamas’ electoral victory proved the best excuse to force BG to cancel the contract.

Jerusalem

One of the most complicated issues in the conflict between Israel and Palestine is the city of Jerusalem. Because of its historical significance for Jews, Christians, and Muslims, Jerusalem was designated as an international city from the very beginning of the British Mandate. With the establishment of the state of Israel, the Green Line cut the city into two parts. The eastern part along with the rest of the West Bank came under the control of Jordan. With the 1967 war, Israel seized the entire city, unified it and later annexed it. UN Security Council resolutions 252 and 476 condemned the decision and declared it null and void.

During the whole period since 1948, Jerusalem’s borders were steadily expanded by Jordan and later by Israel, massively increasing its Jewish population. Jerusalem today is almost four times larger than it was in 1947.

The main demand of Palestinians in various negotiations has been to allow for the establishment of East Jerusalem as the Palestinian capital. Israel, however, considers Jerusalem as a unified city and its own exclusive capital, and as mentioned earlier, has increased the Jewish population while decreasing the Arab populations of East Jerusalem.

Access to surface and groundwater

A cornerstone of Zionist policy from the very beginning has been access to and control of water sources. The Jordan River stretches 156 miles, flowing from Mount Hermon in Lebanon to the Dead Sea, crossing the Sea of Galilee (Bahr-Tabarieh, Lake Tiberias, Lake Kinneret) in Israel and the Golan Heights. It runs through five countries and territories (Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, and Palestine), all of which are technically part of a “riparian regime” for collectively managing the affairs of the river. This arrangement, however, never materialized. As mentioned earlier, Israel first took over the three “demilitarized zones” close to the surface water sources. Later on, it drained Lake Hula swamps, diverted water to the south through its National Water Carrier, and maximized its share of the river. Several attempts by the US in the 1950s to find a negotiated settlement for the water issue failed. Of the five riparian members, Syria and Lebanon were almost excluded from sharing the basin, and Palestinians were denied all access to the river. Thus, presently, only Israel and Jordan are beneficiaries of the river.

Aside from surface waters, Israel also controls the underground waters of the West Bank, which is divided into three (Northern, Eastern, and Western) Aquifers. The second Oslo Accords set Israel’s share of water at four times that of the Palestinians. Nonetheless, Israel continued to pump water far above its assigned quota. In fact, forty percent of drinking water within the Green Line supply comes from West Bank groundwater. In the Western Aquifer, of the total 360 million cubic meters (MCM), Israel uses 340 and Palestinians 20. In the Northern Aquifer, Israel uses 115 MCM out of 140, and in the Eastern Aquifer, Israel uses 60 out of 100 MCM. Palestinians rarely can get permits to drill deep wells, but Jewish settlers are easily allowed to do so.

No doubt, with a relatively larger population, a far more developed industrial society, and one of the most advanced agricultures in the world, Israel consumes plenty of water. It has also a most sophisticated water management system, and in addition to natural water resources, a portion of Israel’s water comes from desalination plants, as well as from recycling of sewage for agricultural use. Yet, the unequal distribution of water and limits imposed on Palestinians and other riparian neighbours regarding access to their rightful quotas have been and continue to be a major source of tensions.

A combination of all these major problems has been the basis of the conflicts and confrontations between Israel and Palestinians that at times have reached an explosive point, problems that have either been ignored or were not dealt with seriously in numerous “peace” negotiations.

Israel/Palestine “Peace” Processes

Since the earliest Jewish immigration to Palestine, and following the Balfour Declaration in 1917, when Britain declared its willingness to establish a homeland for Jews, efforts were made to pacify the Arab inhabitants of the region. The first attempt was a meeting in 1919 between the Zionist leader, Chaim Weizmann and Emir Faisal, a leader of the Arab revolt against the Ottomans. This was in line with the Western countries’ policy and the post-war Paris Conference through which Arabs were supposed to encourage and support Jewish immigration to the region, while Zionists would help Palestinians create a viable stable state. Faisal, however, was by no means a representative of Palestinians and, like Weizmann, disdained Palestinians. The meeting did not achieve anything. Faisal, who the British had appointed as king of greater Syria, was ousted by the French who had gained the mandate of Syria/Lebanon through the secret Sykes-Picot agreement, and the British moved Faisal to Iraq to become king there, while his brother became king of Transjordan.

During the British Mandate in Palestine until the establishment of the state of Israel, several initiatives were put forward in response to growing tensions. Most notably, in 1937, the Peel Commission proposed the partition of territory and assigned a relatively small part of the Mediterranean coast and northern parts to the Jewish state, and the rest to the Arab state, with the exception of Jerusalem, which would remain under British Mandate. The 1938 Woodhead Plan expressed reservations about the possibilities of partition, further limited the territory assigned for the proposed Jewish state, and drastically limited the territory for the Arab state, expanding the areas under the Mandate. None of these plans could be materialized, and Zionist para-military organizations Irgun, and later LEHI, branded as “terrorists” by the British, expanded their activities. Menachem Begin, head of Irgun and later an Israeli Prime Minister, famously said that “the historical and linguistic origin of the term terror prove that it cannot be applied to a revolutionary war of liberation,” a quote that some Palestinians use.

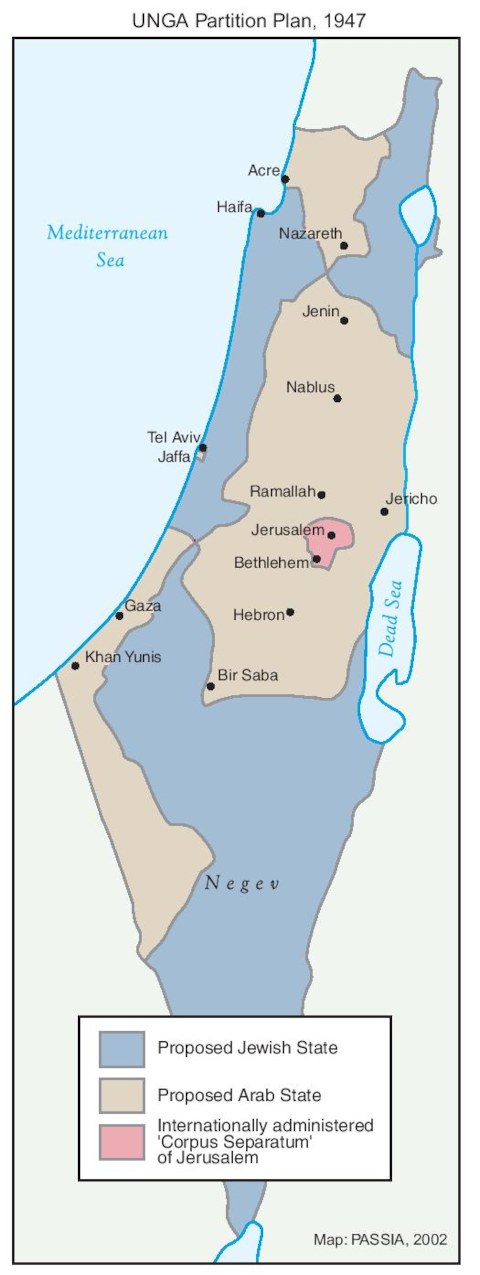

In 1947, Britain, which no longer had the option to maintain the mandate, handed over the “Palestine Question” to the United Nations. Two proposals known as the Minority Plan and Majority Plan were discussed in the General Assembly. The Minority Plan, favored by Iran, India, and Yugoslavia, proposed a single federal state for two peoples, in which each nation would have full autonomy in its territory, but issues such as foreign relations, national security, and immigration would be dealt with at the federal level through a bicameral parliamentary system. This was a very progressive plan but was not acceptable to the Zionists who wanted to establish an independent Jewish state. The Majority Plan had the support of the United States and the Soviet Union and was adopted in Resolution 181, allocating much wider sections of land for the Jewish State compared to earlier British partition plans. Arab states, newly established with very limited diplomatic experiences, voted against both plans, though Israel accepted the Majority Plan. With the war raging on, Israel declared itself a state in 1948, and by the end of the war, it added more territories to what was allocated to it by the UN Resolution.

With the establishment of the state of Israel, and its expansion through subsequent wars, numerous UN Resolutions have dealt with Israel and the Occupied Territories; more than 400 by the General Assembly, and over 222 by the Security Council – excluding 44 resolutions vetoed by Washington. One of the most important Security Council resolutions was 242 in 1967, which along with acknowledging the existence of Israel, demanded its withdrawal from the territories occupied in the 1967 war. Palestinians did not accept the Resolution, as it implied recognition of Israel. Egypt and Jordan accepted it, and later, other Arab states made it a condition for the recognition of Israel. Instead of complying with the resolution, Israel came up with the Allon Plan, proposing the partition of the West Bank, allocating two separate areas assigned to Palestinians to be annexed to Jordan, and the rest remaining under Israeli control. The most intriguing part of the plan was that the two divided Palestinian areas were inside Israel and not bordered by the Jordan River, though the plan allowed a passage to Jordan through Jericho.

The 1978 Camp David Accord between Egypt and Israel failed to get Israel to make any substantive concessions to Palestinian self-determination. It took until 1987 with the first Palestinian Intifada that world attention was brought back to the unresolved Palestinian problems.

Secret negotiations between representatives of the two sides in Madrid in 1991 brought high hopes for peace, paving the way for the Oslo Accords of 1993 and 1995. As mentioned earlier, the West Bank and Gaza were divided into three zones, and seven Palestinian cities and 450 villages scattered across Israeli-controlled territories were granted limited self-government, and the Palestinian Authority (PA) was established. The Oslo Accords did not deal with the major issues of refugees, borders, or Jerusalem, which were supposed to be finalized in subsequent years. This was obviously a lopsided agreement between a stronger side with massive international support and a much weaker side with no comparable support. Yet, the hope was that it would gradually improve the Palestinian condition and pave the way for a real two-state solution. But this did not happen. Israel continued establishing illegal Jewish settlements on Palestinian lands and increased blockades and roadblocks. At the time of the Oslo Accords, the population of settlers in the West Bank was 110,000, and today, without counting the settlers in East Jerusalem, it is over half a million.

Numerous other agreements followed the Oslo Accords. In 1997, the Hebron Agreement divided the city into two sections: Hebron 1 with 240,000 Palestinians, and Hebron 2 for several hundred Jewish settlers. In 1998, the Wye River Memorandum with Clinton, Arafat and Netanyahu, made some adjustments to the Oslo Accords, and a small percentage of the three areas were relocated. The 1999 Sharm el-Sheikh Agreement made further slight changes.

In 2000, President Bill Clinton hosted Israeli prime minister Edud Barak and Palestinian Authority chair Yasser Arafat at Camp David. Clinton and Barak proposed changes to the West Bank borders according to which Israel would annex 9-10 percent more of the West Bank and 9-10 percent more of the border with the Jordan River, which would also be put under “indefinite temporary” [sic] Israeli control. In return, Israel would add 1-3 percent of its own territory in the Negev Desert to the Palestinian territories. Some unspecified parts of Area C would also go under Palestinian control, without any impact on Jewish settlements. Palestinians would be allowed to commute on a highway that would link Jerusalem to the Dead Sea, with Israel having the right to shut it down anytime it deemed necessary. Refugee issues remained unresolved. The proposal would give the Palestinian state administrative control over part of East Jerusalem without “sovereignty” over the Haram al-Sharif/Al-Aqsa Mosque, or the Temple Mount compound. Arafat declared that he could not possibly agree with the proposals and the summit failed. Arafat’s return to the West Bank coincided with the second Intifada, and Israel’s response included demolishing much of Arafat’s residence, leaving a small section for his impending house arrest.

Very important peace talks took place in the Egyptian town of Taba in 2001. While no agreement regarding borders and land divisions was reached, at least on paper it dealt with some major issues pertaining to refugees and Jerusalem. For Jerusalem, instead of dividing it with a border, a reality no longer practical, it suggested that the city be divided into two administrative zones: The western part, Yerushalayim, would be the capital of Israel, and the eastern side, Al-Quds, the capital of the future Palestinian state. More importantly, on the question of refugees, it referred to the 1948 UN Resolution 194 regarding the conditional right of return and compensation, and some concrete suggestions were made: 1- the controlled return of refugees to Israel and Palestinian territories, and to the lands exchanged between the two parties; and 2- refugees formally becoming citizens of where they had settled, including transfer to a third country.

This agreement was certainly a major step forward in resolving the Israeli/Palestinian conflicts. But it coincided with the election of George W. Bush and the neo-cons in the US, the end of the Barak government, and Ariel Sharon coming into power in Israel. More significantly, Ehud Barak was not serious about this deal. In 2003, at a conference of the Tel-Aviv and Al-Quds Universities mentioned earlier, where the American, Israeli, and Palestinian negotiators were reviewing the failure of the Camp David II Accord, Barak openly admitted that he was not serious about the deal, and prompted the anger of the chief Israeli negotiator present in the conference. (Arafat could not attend because he was under the house arrest!) In fact, just before handing the government to Sharon, Barak sent a note to the new US president stating that what had been agreed in Taba and in Camp David II was not considered binding on the new Israeli government.

In 2001, Ariel Sharon unilaterally, and outside any negotiations, proposed the Sharon Plan that comprised some minor changes in the territories assigned earlier to Palestinians while expanding the areas under Israeli control in all of the Jordan River valley and the Dead Sea.

In 2002, George W. Bush, through the ‘Quartet’ (US, EU, UN, Russia) suggested Roadmap 2002, which was in actual fact a road to nowhere: in the first phase Palestinians were to renounce violence, Israel to withdraw to pre-September 2000 (2nd Intifada) borders and freeze those settlements built since 2001. In the second phase, a Palestinian state would be established, and in the third phase, an international conference would resolve the finalized borders and the question of Jerusalem.

The Arab states came up with their own Arab Peace Plan, which put forward three conditions for peace and the formal recognition of Israel: withdrawal to the 1967 borders, resolving the refugee issues on the basis of UN Resolutions, and the creation of a Palestinian state with its capital in East Jerusalem. Israel rejected the idea.

In 2003, pro-peace Israeli and Palestinian political figures and activists met unofficially and came up with the Geneva Initiative. In terms of borders and territory, they suggested a land swap, assigned much of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip to Palestinians, but agreed that the areas close to the Green Line with significant Jewish population would be annexed to Israel. In return, part of the Israeli territory close to Gaza would be annexed to the Palestinian side. On the refugee question, however, there was no breakthrough.

Time was passing, and key Palestinian issues remained unaddressed. Following years of house arrest, Yasser Arafat was sent to France for medical reasons and mysteriously died in 2004. Internal strife among Palestinian political currents intensified, and the movement was eventually divided into two distinct parts.

All sorts of subsequent meetings and summits were held without any serious results. In 2005, representatives of Israel, the Palestinian Authority, the King of Jordan, and President of Egypt met in Sharm al-Sheikh. In the Riyadh Summit of 2007, Arab leaders repeated the earlier Beirut declaration. At the Annapolis Conference in the same year, George W. Bush, Ehud Olmert, and Mahmoud Abbas attempted to revive the “Roadmap” peace talks, but no agreement was reached. A notable part of this initiative was Olmert’s agreement to assign a section of East Jerusalem to the Palestinian state. With the election of Barack Obama, there were hopes for the negotiated settlement he had promised. But in the 2010 and 2013 Conferences, Obama, Netanyahu, and Abbas could not achieve any progress. In 2014, after confrontations between Israel and Hamas, Netanyahu cancelled all efforts for peace negotiations. During the Trump presidency, any pretense of a peace process between Israel and Palestine was set aside altogether, and the ultra-right Israeli coalition had no interest in any negotiated peace with Palestinians anyhow. The Abraham Accords merely aimed to bring together Arab autocracies and Israel and did not address the Palestinian question. And the Joe Biden Administration did not undertake any major initiatives either.

In short, none of the so-called peace processes resolved any of the Palestinian problems discussed earlier. On this long journey, entrenched frustrations and anger have conjoined periods of calm before storms and outbursts. The first intifada prepared the ground for the Madrid and Oslo negotiations, and the second Intifada brought the Taba Summit. The latest horrific attack by Hamas, brutally killing many civilians and taking hostages, followed by the unimaginable brutality of the Israeli response and the collective punishment and killing of thousands of Gazans, has once again attracted world attention to the ongoing Palestinian/Israeli conflict. Whether this will lead to a new round of peace negotiation following the completion of military operations remains to be seen.

Without a doubt, the effects of the October 7 attacks did not serve the Palestinian cause at all. The major difference between this confrontation and the two Intifadas is that it is led by a reactionary obscurantist religious fundamentalist force that, ironically, gave the best excuse to another fundamentalist force in power in Israel to mercilessly kill many thousands of Palestinians and justify its expansionist policies.

Are There Any Solutions To This Lasting Conflict?

With the total failure of the Oslo initiative, many question the idea of a so-called two-state solution. Putting aside ideas of a Palestinian state in the pre-1948 borders or “from river to the sea”, some (re-)emphasize the one-state solution for the two peoples, not taking into consideration the basic tenet of Zionist ideology that rests on having a homeland for Jews. Whether one agrees with this ideology or not, it is a reality that cannot be ignored. The one-state solution is, without a doubt, an ideal that might be materialized in future. However, there is no chance of its fulfilment any time soon. It is important to note the so-called “demographic dilemma”: today the population of Israel is 9.7 million, which consists of 2.1 million Arabs and about half a million people of other ethnicities or religions, making the Jewish population of Israel around 7.1 million. The Palestinian population of the West Bank and Gaza is about 5.4 million, and if added to the non-Jewish Israeli population, Jews would become a minority in the Jewish “homeland”. Although Israel encourages Jewish immigration and so far, about nine major waves of immigration have taken place, and notwithstanding the very high birth rate among ultra-orthodox Jews, Israel’s overall Jewish population growth rate is lower than the Palestinian population, despite the vast numbers killed every year in numerous conflicts.

Some on the left have also put forth the idea of a potential collaboration of the working classes on both sides against the dominant capitalist class. This is a nice idea with no basis in reality. Histadrut, the powerful Israeli General Federation of Labour, federating over twenty industrial trade unions with about 800,000 members, is still one of the most powerful institutions in the country, despite being weakened by the increased dominance of neoliberalism in Israel since the 1980s. It is a progressive movement for Israeli workers and even has over 100,000 Arab members. But as a founding Zionist institution it has never taken a strong stance in relation to the post-1967 Occupied Territories. On the Palestinian side, the General Federation of the Palestinian Trade Unions, with about 290,000 members, despite defending Palestinian workers, is very close to the Palestinian Authority, has little actual power, and like many other trade unions suffers from a lack of internal democracy. In short, the expectation that under the present conditions, workers on both sides would unite to challenge the dominant power is unrealistic.

The reality is that the two-state solution was never truly on the agenda. Even what in 2010 I poignantly called a One-and-a-half State Solution was never materialized. And yet, all things considered, the only solution to the 75-year-old conflict is a real two-state solution. The peace negotiations mentioned above, although all have failed, carry the seeds of a practical, realistic, and relatively fair solution. If real conditions of peace are provided, they can provide the basis for a lasting agreement.

The main question, though, is what are these real conditions for peace. Contrary to the present situation in which reactionary, ultra-conservative, and fundamentalist political currents on both sides are facing off, I believe, it is ultimately the progressive secular currents that will play the major role in finding lasting peace. So long as there are no major changes in Israeli civil society and politics, and the progressive Israeli left and liberal forces are sidelined by the reactionary right-wing zealots, there cannot be any hope for peace, and the world will witness more periodic outbursts. Also, if similar changes do not happen on the Palestinian side, and progressive Palestinian forces are not able to effectively confront the inept and corrupt Palestinian Authority on the one hand, and religious fundamentalism on the other, and create a unified progressive secular front, they will not have a strong voice in the future peace process. It is obvious that these are big ifs, and numerous powerful regional and international factors, ranging from imperialism, US politics in particular, and religious fundamentalisms (Jewish, Christian, Islamic), as well as regional autocracies, and proponents of antisemitism and Islamophobia, present major barriers to genuine peace between Israel and Palestine.

Thus, it is difficult to be optimistic, but there is no other choice but to remain hopeful and work hard to find practical and progressive ways to move towards peace based on a two-state solution through which a viable secular democratic government for Palestine is established within the pre-1967 borders with its capital in the Eastern part of unified Jerusalem, along with negotiated land swaps based on the Geneva Initiative, resolving the refugee problem based on UN Resolutions and the Taba agreement, and fair division of water sources and land and maritime borders. •

This article first published on the New Politics website.