Healthcare Funding Crisis: Unpacking the Ontario Government Economic Statement

Today [November 2], the Ford government will release its fall economic statement. This briefing note is intended to give context with which to assess the claims of the government. As we write, Ontario is in the worst healthcare crisis in memory. The most urgent services in local public hospitals are facing repeated and unprecedented closures, including maternity and emergency departments. Intensive care units are desperately understaffed, putting patients at risk. Tens of thousands wait for long-term care. An unprecedented staffing crisis extends across hospitals, long-term care, primary care, home care and EMS. Minden has lost its emergency department. Fort Erie and Port Colborne’s urgent care centres – which were supposed to replace their closed emergency departments – have been closed down. This year, there have been more emergency department closures in Ontario than ever in our history. Small, rural and local communities are up in arms, fearing that their local emergency departments will be permanently closed also.

In this scale of emergency, one would expect that extraordinary efforts would be made to stabilize and improve healthcare. Instead, the provincial government is increasing healthcare funding at less than the rate of inflation – a real dollar cut – and funding plans are far less than needed, even to meet the announced plans of the government. The following briefing note gives the data and the context in which to understand where our health funding ranks and what the budget announcements mean for actual services.

Overall Healthcare Funding

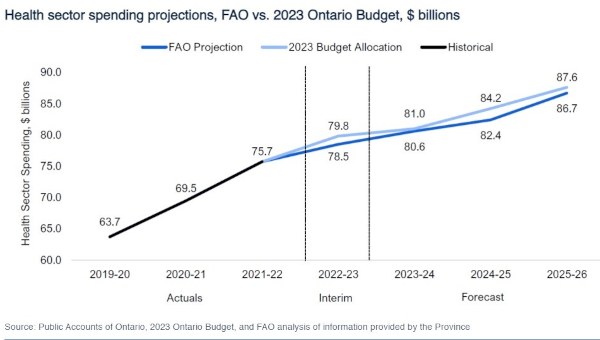

According to the Ontario’s Financial Accountability Office (FAO), an independent body that reports to the Legislature of Ontario, much like the Auditor General, the healthcare budget for this year was expected to increase by $1.2-billion ($79.8-billion to $81-billion) a 1.2 percent increase.1

Statistics Canada reports that healthcare inflation is 5.6 percent (measured as per the most recent figures available covering the time period of September 2022 – September 2023).2

“The budgeted increase for healthcare this year is less than the rate of inflation, in economists’ terms, a ‘real dollar’ cut.”

Next year, from 2023-24 to 2024-25, the budgeted increase for healthcare is 3.2 percent.3 In the year following, 2023-24 to 2025-26 (leading into the spring election in 2026) the budgeted increase for healthcare is 3.4 percent.4 Projected spending increases as we get closer to the next election but for this year and next, budget increases for health funding do not meet current or projected inflation.

The usual measure for health funding need is inflation, population growth and ageing, and sometimes an increased utilization adjustment (under various different names).5

Population growth projections from the Ontario government show that the provincial population is projected to increase at an annual rate of 3.2 percent in 2022–23, 2.7 per cent in 2023–24, and 2.1 percent in 2024–25. Usually, aging is projected to add 1 percent annually.

To maintain existing services as population grows, to account for inflation, and provide for the needs of our population as it ages, without any major improvements in service, funding would need to increase by an amount equal to population growth (3.2 percent – 2.1 percent), aging 1 percent, and inflation which is projected to decrease from its high of over 5 percent down to the 3-4 percent range.

“The budgeted increase for healthcare this year and over three years is significantly less than needed to meet inflation, population growth and aging, even without any significant improvements to services.”

Actual spending vs. budget

The Ford government has made a practice of announcing health funding plans in its budgets and public announcements but not actually spending the money.

- The most recent quarterly report of the FAO shows that actual health spending in the first quarter of this fiscal year was approx. $1.2-billion less than planned. (End of first quarter 2023-24.)6

- By the end of last fiscal year (2022-23) the FAO reports that the provincial government spent $312-million less than planned on healthcare.7

- By the end of 2021-22, the FAO reports that the provincial government spent $1.8-billion less than planned on healthcare.8

- By the end of 2020-21, the FAO reports that the provincial government spent $1-billion less than planned on healthcare.9

The Ford government has repeatedly underspent its planned healthcare budget for years, choosing to impose real dollar wage cuts as staffing shortages worsened and refusing to increase service levels even as healthcare services have fallen into unprecedented crisis.

Can we afford it? Yes, we can. Everyone else does.

Ontario ranks at or near the bottom of the country in key healthcare funding measures

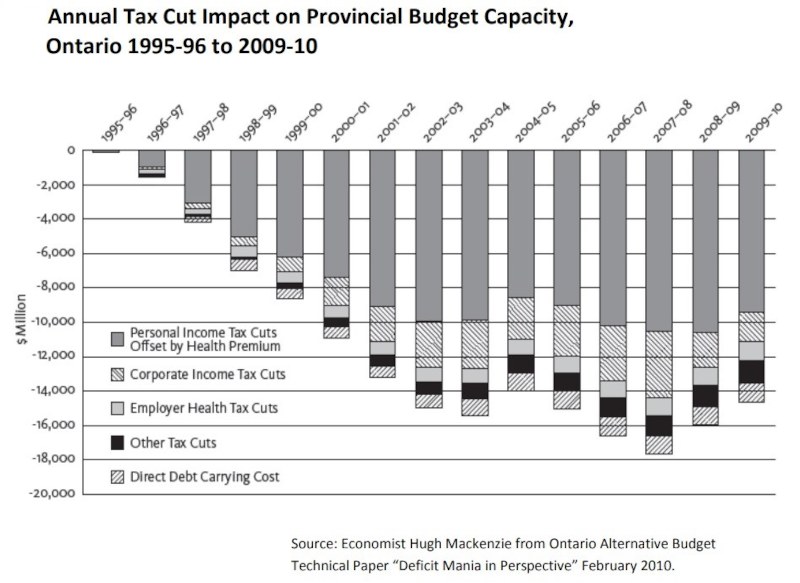

Ontario ranks last of all provinces in provincial funding for all public services. In the 1990s, the Harris government’s major cuts to taxes – primarily benefiting high income people and corporations – resulted in $15 per year less in provincial revenues that could be used for public services and social programs. Subsequently, the McGuinty government cut corporate taxes further by additional billions per year. (See Chart below.) As Ontario dropped to the bottom of the country in funding for our public services, it also dropped to near the bottom of the country in funding for healthcare.

Currently Ontario funds healthcare at a lower rate than most other provinces.

- On a per-person basis, Ontario ranks second last in Canada.

- As a percent of provincial GDP, the most accepted measure of affordability, Ontario ranks third from the bottom of the country in healthcare funding.

In particular sectors, such as funding for public hospitals, Ontario ranks dead last in Canada.

- On a per-person basis, Ontario ranks last in Canada.

- As a percent of provincial GDP, Ontario ranks last in Canada.

See footnote for more information.10

“The evidence shows that there is plenty of room for growth, even to come up to the average of other provinces.”

Ford government announcements of improved capacity are not possible given their budget plans

According to the FAO.11

- The Ford government has announced commitments to expand capacity in hospitals, home care and long-term care. However, these increases in capacity will be more than offset by increases in demand for these services from Ontario’s growing and aging population. Relative to projected growth in demand, by 2027-28, Ontario will have less hospital capacity, similar home-care capacity and less long-term care capacity compared to what it had in 2019-20. Note: hospital overcrowding continues to be a major problem, there are more than 39,000 people on wait lists for long-term care, and home care continues to be poorly organized and inadequate.

- From 2022-23 to 2027-28, the province has allocated $21.3-billion less than will be needed to fund current health sector programs and deliver on its expansion commitments in hospitals, home care and long-term care.

- Ontario is currently experiencing shortages of nurses and personal support workers (PSWs), which is projected to persist through the FAO’s six-year forecast period. Even with the announced government measures to increase the supply of nurses and PSWs, by 2027-28, the FAO projects a shortfall of 33,000 nurses and PSWs. These nurse and PSW shortages will jeopardize Ontario’s ability to sustain current programs and meet program expansion commitments.

Federal Funding Share

According to the FAO, federal government funding covers about 24.5 percent of provincial healthcare spending in 2022-23. The federal share will increase to 27.4 per cent in 2023-24. However, federal transfers as a share of Ontario health sector spending will then gradually decline to 26.1 per cent in 2027-28, due to the expiry of some time-limited funding agreements. Over the three-year period from 2023-24 to 2025-26, the FAO estimates that the increase in federal health transfers to the province is $4.1-billion. •

This article first published on the Ontario Health Coalition website.

Endnotes

- https://www.fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/health-update-2023#_ftn3

- Source: Statistics Canada. Table 18-10-0004-08 Consumer Price Index, monthly, percentage change, not seasonally adjusted, Canada, provinces, Whitehorse and Yellowknife – Health and personal care.

- https://www.fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/health-update-2023#_ftn3

- https://www.fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/health-update-2023#_ftn3

- By the 2018 election there was a deep consensus that >5% hospital base funding increase was needed. This was based on the following:

“In the December 2016 Federal-Territorial-Provincial Finance Ministers’ meeting, the provinces and territories were calling for a Canada Health Transfer escalator that would match projected healthcare cost growth at 5.2 percent. This aligned with the Parliamentary Budget Office of the federal government prediction of a funding growth need. The Financial Accountability Office of Ontario set the needed rate at 5.2 percent. The Conference Board of Canada supports the calculation of a 5.2 percent cost projection. Health provider organizations issued public policy papers and statements supporting the 5.2 percent figure. This figure was also supported by the Canadian Health Coalition, the Ontario Health Coalition and coalitions across Canada.” See further information here.

- https://www.fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/2023-24-expenditure-monitor-q1

- https://www.fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/2022-23-expenditure-monitor-q4

- https://www.fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/2021-22-expenditure-monitor-q4

- https://www.fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/2020-21-expenditure-monitor-q4

- https://www.ontariohealthcoalition.ca/wp-content/uploads/FULL-REPORT-February-10-2012.pdf

- https://fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/health-2023