AMLO’s Neoliberalism in Mexico: Extractivism, Militarism and Climate Breakdown

Edwin F. Ackerman has written a review of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s (AMLO) presidency in the pages of New Left Review. Ackerman’s take is a generous one. While he remains critical of some of Lopez Obrador’s most indefensible positions (such as the increase in assassinations of journalists and land defenders, and his response to the feminist movement), he (deliberately or not) ignores some of the most problematic aspects of his administration such as his complete disregard for the climate crisis, the rampant increase and progressive militarization of almost all aspects of social life, and an incoherent energy ‘security’ policy relying on extracting already waning fossil fuel reserves and natural gas imports from the United States.

In this essay, I take these three points to complement Ackerman’s analysis of AMLO’s ‘anti-neoliberalism’, refuting the condescending way he engages with what he calls the “cosmopolitan intelligentsia and neo zapatista-adjacent autonomists.” Ultimately, I question whether AMLO’s project can accurately be referred to as ‘anti-neoliberal’.

1.

Ackerman anchors his analysis of AMLO’s anti-neoliberal project on three main points: the reinstatement of class cleave and a primary organizer of the political field, the effort to concentrate the power of a state apparatus hollowed out by decades of neoliberal governance, and a break with corruption. While the anti-neoliberal label seems to encapsulate all of AMLO’s government’s promises, apart from a considerable increase to the minimum wage in the early months of his administration, there is little that can be called ‘anti-neoliberal’. Unlike some countries in the Latin American region, the neoliberal turn in Mexico happened before electoral democratization took place. This means that neoliberalism remains entrenched in Mexico’s incipient electoral democracy. The embeddedness of neoliberalism quickly became clear as AMLO took on the presidency. By quickly shifting his rhetoric from talking about ‘the power mafia’ during his electoral campaign, he has used the term ‘conservatives’ to broadly define any opposition to his government, which includes feminists, journalists, environmentalists, a xenophobic/classist right wing, ‘the middle class’, and even the Zapatistas.

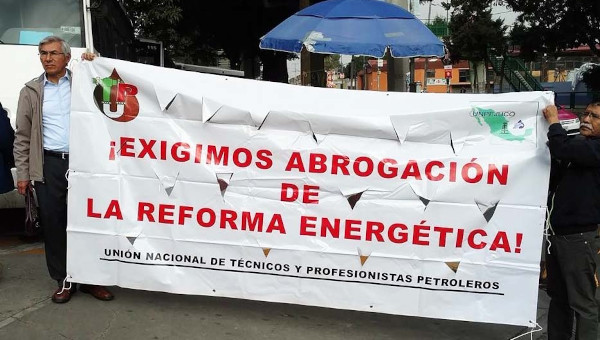

The basic fact is that AMLO’s government has not made substantial changes to the regulatory framework. The country still operates under the neoliberal framework consolidated over the last three decades, most notably the 2013 Constitutional Reform, which AMLO heavily criticized for opening private investment into the energy sector. Despite enjoying one of the most comfortable majorities in Mexican democratic history from 2019 to 2022, AMLO’s government has not made significant changes to either the taxation structure, the energy or the extractive policies deployed by previous governments, and in the latter cases, only temporarily halting new contracts and mining concessions. Instead, the government has chosen to defund several state agencies under a ‘republican austerity’ program, most notably the environmental and regulatory entities, to fund a nationalistic development project which entails substantially increasing funding for dirty energy sources and the military.

AMLO is no stranger to neoliberal policies – he has been open to further expanding economic integration with the US and Canada – by critiquing NAFTA but hailing the USMCA – and has systematically followed neoliberal policies like dogma: expanding megaprojects, inviting international financial investment, and giving citizens direct cash payments. These cash transfers, as Ramon I Centeno has recently argued, are nothing new: they are, in fact, a trademark of neoliberal governments in Mexico. Despite these being key in reducing the expansion of poverty and benefiting the situation of the most precarious conditions of life for many, they do very little to change the overall context. AMLO has instead used this mechanism to pact with powerful business elites (the likes of Alfonso Romo), calling it ‘pragmatic’ to maintain a business-friendly status quo while using the cash delivery payment – borrowing form the old tactics of Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) and Partido Acción Nacional (PAN) – to create a solid voting block of support instead of expanding state capacity, either for providing health or social projects.

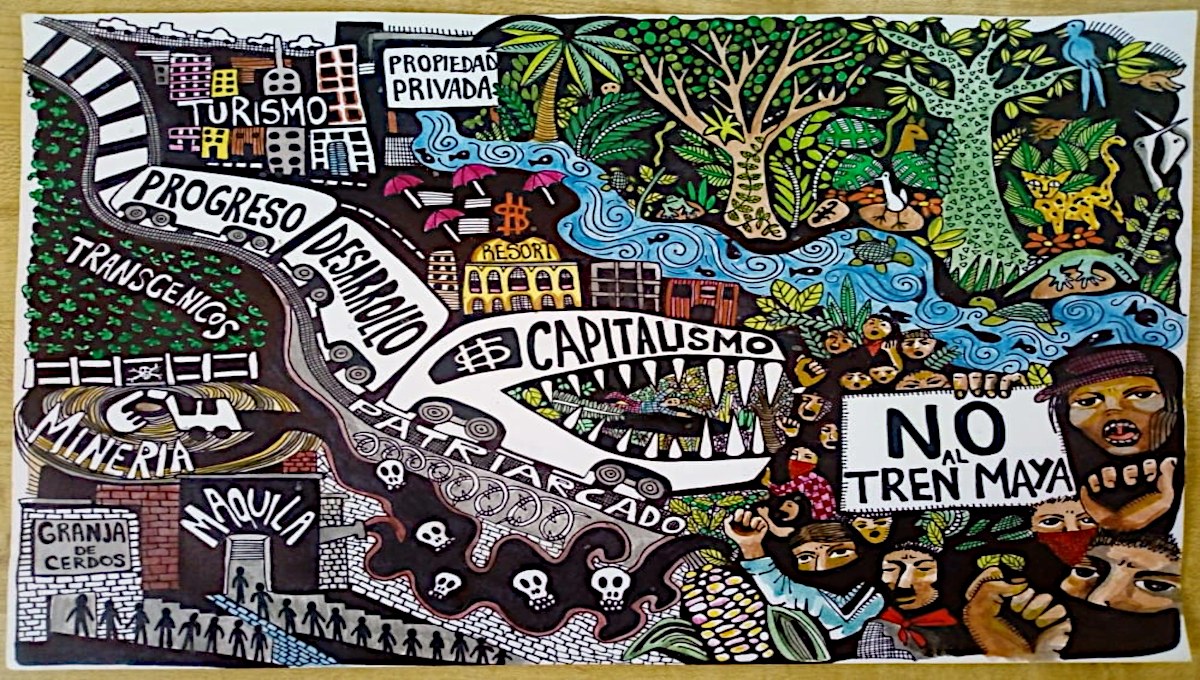

The president has used the impressive feat of retaining popularity with over 60% approval ratings to justify any of his programs. Using flawed popular consultations and direct referendums in which less than 2% of the national electorate actually voted, the president has created a discourse of popular legitimacy around his pet projects, which include the costly (now 130% over the estimated price) and problematically called “Maya Train,” in the five southeastern states of the country, a new airport – spawned after the cancellation of a previous one – a geopolitical regional consolidation project of what is known as the interoceanic corridor and a new 8 billion dollar mega-refinery that aims to process 340,000 barrels of oil per day. The deployment of these projects has been done mostly by sidestepping any environmental and social regulations and concerns, instead branding them as part of a broader strategy of ‘national security’ and deploying the newly created national guard to construct and secure their development.

While framed as integral for the country’s economic development and growth, these projects are, in reality, rehashes of regional development programs proposed under the neoliberal era (most notably the Plan Puebla Panama under Vicente Fox in the early 2000s). Furthermore, these projects deploy the neoliberal era’s special economic zones – or places where the traditional regulatory frameworks are relaxed to encourage financial investment and extraction, a trend that is now clearly visible in the Yucatan Peninsula.

Through these measures, AMLO’s government effectively reduced civilian oversight over the military, put the military in charge of traditionally civil duties, and centralized power in his presidency, promising growth, jobs, and development through the deployment of mega infrastructure projects.

2.

Lacking in Ackerman’s analysis is AMLO’s complete disregard for the climate crisis and environmental breakdown, as well as the links this has to the socio-ecological policies he has promoted. By openly dismissing Mexico’s vulnerability and responsibility to climate change – his own government recognizes that at least 59% of all municipalities present high and very high levels of vulnerability – AMLO has operated consistently under an idea of reconstituting state power through extraction. Very much like some of his counterparts in South America over a decade ago, the government has increased fossil fuel extraction, nationalized lithium reserves, and deployed large-scale region-reconfiguring projects aimed at increasing economic growth, instead of pushing for real (re)distributive measures. For example, the Maya Train, problematically labeled ‘sustainable’, has devastated and fragmented fragile ecosystems, fueled land speculation practices, and wrongly consulted communities about the impacts and supposed benefits, without respecting national and international standards for adequately obtaining indigenous people’s consent. Similarly, the other projects, including the transoceanic corridor and the Santa Lucia airport fit into a broader project of creating a new transit hub from the North to the South and between oceans, which have largely ignored or shrugged off any socio-ecological concerns.

This is particularly true for AMLO’s energy policy, which Ackerman places front and center of his anti-neoliberal agenda. While publicly denouncing low-carbon infrastructure as ‘corrupt’, AMLO has instead used his majority in both chambers of Congress to focus on strengthening the Federal Commission of Electricity (CFE) and PEMEX, the latter still representing an enormous public debt. Mexico’s energy conundrum is indeed serious, the country having surpassed peak oil production in 2004 and reached a limit in natural gas production in 2009. Since then, output has decreased steadily while imports have risen proportionally. By heavily investing in exploration, AMLO’s government has managed to sustain production of roughly 1.7 million barrels per day, but the data clearly shows that continued extraction will be more costly, increasing social and ecological impacts. Regardless, AMLO has systematically increased PEMEX, CFE, and the Ministry of Energy’s budget, targeting ‘republican austerity’ on environmental and regulatory entities and funds. The president has said that the goal is for Mexico to become self-sufficient in the production of processed fuel (instead of exporting unprocessed resources), something he seeks to achieve with the addition of the Dos Bocas refinery and the purchase of the Deer Park refinery in Houston, Texas, in 2022.

Crucially, the claim of self-sufficiency, which is usually linked to an idea of anti-neoliberal sovereignty, has paradoxically excluded from the public debate the deep reliance on natural gas imported from the United States – Mexico currently imports 72% of the natural gas it uses, and it remains the main fuel it relies on for electricity generation (62%). AMLO, far from doing anything to reduce this dependency, decentralize and democratize the energy system, or tackle energy poverty,an issue that affects approximately 38% of households in Mexico, which will inevitably get worse with climate breakdown, has celebrated the construction of new gas infrastructure that will lock in dependency on US production. This is the case for the problematic Puerta al Sureste gas pipeline project in an alliance between CFE and TC Energy and the planned construction of six new gas-based power plants.

When questioned on the lack of climate policies, AMLO instead pointed to the rehabilitation of the country’s hydroelectric dams and the ‘Sowing Life’ program in the south as part of his climate agenda. However, these policies have been heavily criticized for their lack of scientific assessment, as they provide no real evidence of reducing emissions, while, simultaneously, concerns about the latter program have been raised, mainly about the impacts on biodiversity in native forests and the possibility of increasing deforestation rates. Nevertheless, it can be argued that some changes were made, at least in challenging the traditional neoliberal agricultural model.

The program has also been criticized for its added political benefit, AMLO has argued for an expansion of the program to Central America to enforce the US agenda of curbing migration to the North. In 2022, after clear pressure from the US government, which is now in a cold-war-like military dispute with China, the government put together what seems to be an impromptu regional transformation plan for the state of Sonora. Taking advantage of AMLO’s ‘nationalization’ of the country’s lithium reserves – of which dimensions and viability of exploitation remain highly questionable – the government has begun building the biggest solar park in Latin America on Indigenous sacred lands, disregarding socio-ecological impacts and expanding electric car and semiconductor manufacturing as well as grid and port capacities. While this seems to be a reversal of AMLO’s rejection of low-carbon infrastructure, it, in fact, reinforced AMLO’s commitment to putting the CFE first while clearly revealing the influence of the near-shoring efforts from the US’s dispute with China.

Perhaps the most gruesome of these statistics is AMLO’s dismal record on human rights. In 2022, it was reported that a journalist is attacked every 13 hours, with organizations recording at least 696 attacks that year. Since the start of his presidency, at least 42 journalists have been murdered, with 15 deaths in 2022 alone. That same year, the country recorded the grim figure of 100,000 missing people. The same can be said for land defenders: from 2017 to 2021, Mexico registered 102 murders, mostly related to the expansion of mining, logging, and the deployment of megaprojects; in 2022 the country registered an additional 45 killings of land and human rights defenders. While this trend did not start with AMLO, the president’s unapologetic doubling down on the push for ‘sustainable’ development through extraction and megaprojects has only exacerbated the problem. This trend became especially clear early in AMLO’s tenure after the assassination of Samir Flores, which the president chose to dismiss and continue to carry out his predecessor’s “Proyecto Integral Morelos.” Infuriatingly, when confronted about these statistics, the president has systematically dismissed them as ‘conservative propaganda’ and rejected them as either ‘manipulations’ from his opponents or as a ‘ruse’ to downplay his government’s achievements.

The rampant increase of violence in Mexico has led the president to justify a systematic expansion of the military into everyday life. A recent report finds that AMLO has expanded the military to 27 tasks,which go from its ‘traditional’ tasks such as securing borders, all the way to managing social programs, distributing fertilizers, constructing and operating the Santa Lucia airport, and the Maya Train, remodeling abandoned hospitals and managing the Welfare Bank. The progressive militarization has expanded concerns of human rights abuses, a lack of thorough investigations, a normalization and permanence of the level of violence, and a disregard for the evidence that the deployment of the army and the navy has not proven to be an effective policy to reduce violence.

3.

While the right has descended into a racist and classist rejection of AMLO – as articulated by some groups like FRENA – the dismissal of any opposition to AMLO as ‘conservative’ or classist is problematic, to say the least. Ackerman argues that critiques from the ‘left’ come from a “‘progressive’ cosmopolitan intelligentsia and neozapatista-adjacent autonomists” that should instead acknowledge some of AMLO’s advances – while critiquing gender, border, and austerity programmes. He then argues that the ‘left’ has missed an opportunity to build a “serious alternative to MORENA,” while autonomist movements have “abandoned this terrain long ago and focused instead on opposing development projects, with little to show for it.”

AMLO’s anti-neoliberalism remains merely a discursive and rhetorical tool to accommodate a particular form of populism and maintain businesses as usual with powerful elites. In other words, neoliberalism remains alive and well in Mexico. The president and the fourth transformation have instead centralized power and disarticulated any social movements and networks through the deployment of a populist agenda and promises of development. In these sense, I would agree with Ackerman that the left has no project, but this is both because AMLO captured a significant part of the civil society coalitions who saw his project as a real alternative and because the communitarian alternatives remain concerned with their own survival in what seems to be a permanent war against drug cartels, paramilitaries and the Mexican State – think of feminists, Zapatista communities and other autonomists movements. Furthermore, giving-up the idea of capturing state power comes from a conceptual and practical experience of the limits this task has shown, a clear example of this is the Pink Tide in South America in places like Bolivia or Ecuador.

One should question more seriously what it means to capture state power after the Pink Tide in Latin America. AMLO’s presidency might be different from most of his counterparts, but it again shows the limits of actually transforming conditions through state power. Meanwhile, communities in Mexico, embattled by almost 20 years of open conflict and violence are struggling to keep autonomist politics alive. Saying that they have “nothing to show for it” downplays the incredible feats of land and communal defenders struggling to retain territorial sovereignty against the interests of the State and capitalism. I have no doubt I will be branded part of the cosmopolitan Intelligentsia and Zapatista-adjacent autonomists that Ackerman critiques, but AMLO is no leftist; he is rather a manager of capitalism, albeit a better one than any of his recent predecessors. His presidency can be seen as a counterinsurgency movement that has reduced, closed, and repressed the autonomic push of organizations, movements, and networks. As the Zapatistas would argue, AMLO is simply “the new manager of the finca.” In Mexico, the structures of power remain intact. No real ‘leftist’ alternative seems to be brewing a real end to neoliberalism.

Ultimately, even if AMLO’s policies result in alleviating the symptoms of our current civilizatory crisis in the short term – i.e., providing a cash influx for the poorest, empowering unions and building resource nationalism – without actual changes to the regulatory structures or power relations this could mean a recipe for disaster in the mid-run. The next president of Mexico, no matter who (s)he is, will not hold AMLO’s popularity and appeal to most of the people. Indeed, as Ramon I. Centeno argues, AMLO is perhaps the only common denominator of 30 million atomized people, regardless of policy outcome or contradictory twists and turns in his discourse. But this is an identity that AMLO has built over the last 20 years, something that will be hard to match by any other single individual. While there seems to be little to suggest that his legacy will be shaken, the possibilities of justifying most of what the next government will have to face without his leadership – rampant climate breakdown, declining fossil fuel production, rising economic inequality, violence, extractivism, and the consequences of AMLO’s development projects – will not be so swiftly navigated. •