Deflation Interrupted?

To fully grasp the import and potential staying power of the sudden, dramatic spike in consumer price inflation requires that we briefly step back in time to look at the constituents of the neoliberal world that took shape from the 1980s. Paradoxically, as will be shown, these came together to crystallize the opposite trend.

Decades of relatively crisis-free post-war ‘golden age’ accumulation came to a close, first in the United States (US) in the late 1960s, then across other major advanced economies by the early 1970s (excluding Japan), and rates of profit in production-centered businesses began to fall. Why this was the case stemmed from the fact that in relatively closed ‘economic nationalist’ economies, with the absorption of post-war industrial reserve armies, rising labour costs could no longer be offset by technological innovation, leading to raising rates of exploitation. This latter problem was exacerbated by the reaching of the upper bounds of capacity utilization in economies where sales of consumer durables were dependent upon wages paid to workers.1

An ensuing wage-price spiral, accompanied by increased welfare-state spending as unemployment and economic malaise spread, with these inflationary tendencies accelerated by oil price rises from 1973 and US military spending following the demise of the Bretton Woods monetary system, all served to impel inflation across the globe. The subsequent pairing of economic stagnation and inflation in stagflation set the US and global economy on a crisis trajectory.

Skyrocketing Interest Rates in the 1980s

Unilateral, astronomic raising of US-dollar interest rates from the 1980s followed by interest rate hikes in other major economies served to slay the inflation dragon. But, with interest rates well above depressed rates of profit, the golden age of economic nationalist full-scale integrated industrial economies began to unravel. As well, in a world of dollar debtors from local governments to much of the third world, the US banking system veered toward collapse. While the US government was able to bail out its financial and corporate sector, the third world was encumbered in perpetual debt. Subsequent IMF- and World Bank- imposed ‘structural adjustment’ and austerity policies made these economies vulnerable to the graver economic destruction to come.

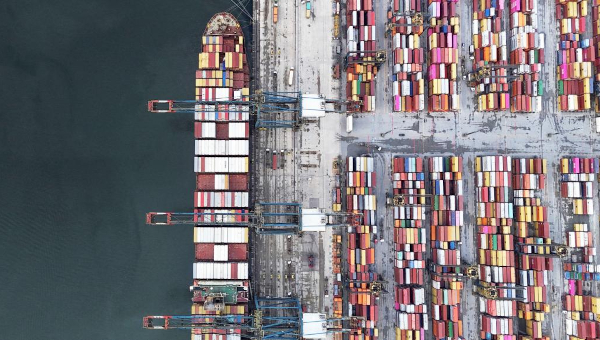

At this global crossroads, two cardinal problems confronted capital.2 First was the question of how to raise rates of exploitation to restore or increase corporate profitability in main production sectors. Simply transferring the golden age full-scale integrated industrial economic nationalist model elsewhere would only bring other economies within the ambit of those conditions that capital was seeking to escape. What is euphemized as globalization, where full-scale industrial advanced economies disintegrated their production-centered accoutrement, it seemed that disarticulating production across value chains traversing low-wage third world economies was the solution. In the latter, surplus quasi-peasant, quasi-proletarian labour forces could be paid wages below their costs of reproduction. It is so very instructive to see the World Bank peddling, as ‘development’ policy, this global pattern of third world off-farm labourers ‘floating’ into contingent work in sweatshops or construction while maintaining their family ‘footholds’ in subsistence farming.3

In advanced economies, major ‘branded’ companies concentrated on core competencies of invention and patenting, design, R&D, and so forth, which, with factories and pesky labour forces removed from their balance sheets, returned them to profitability. This edifice, that saw advanced economy corporations retain global suzerainty, was enabled by the information and computer technology (ICT) revolution. With China’s gargantuan floating quasi-peasant, low-wage labour force integrated into global value chains (GVCs) by the 1990s as an assembly mill, notwithstanding the attrition against unions and slashing of social wage benefits in major advanced economies, mass publics continued to whet their consumption appetites for the exploding array of gadgetry and fast fashion resulting from globalization’s biggest export – deflation!

The second problem was how to deploy bloating pools of idle funds facing scant opportunity for investment in capitalist profit-making production-centered activities, given that much of the productive accoutrement of major economies was disinternalized and disarticulated across the globe to non-equity mode-of-control supplier firms. This problem was amplified by oceans of social savings in pension and insurance funds desperately seeking yield under conditions where secure ‘blue chip’ investment opportunities evaporated with the industrial disintegration of advanced economies. It was precisely this conundrum that compelled the ‘freeing’ of idle funds through waves of deregulation in domestic economies and ‘big bang’ international liberalization of national economies to all manner of speculative financial flows and arbitrage gambits. Smashed also was the 1930s Depression-era firewall separating commercial banking from investment banking and insurance. In fact, the advent of securitization of debt to be traded on secondary markets, by permitting banks to offload illiquid assets from their balance sheets to ‘investment vehicles’, reduced the amount of capital that financial systems had to hold against lending opening the door to orgies of speculative credit origination and the generation of a raft of arcane financial instruments.

However, the fact of exponentially growing debt feeding a financial system revolving around securitization supplanted commercial ‘relationship’ banking with an ‘originate-to-distribute’ model in which banks increasingly disregarded the credit worthiness of borrowers as loans they originated for fat fees were summarily shifted off balance sheets onto securitized financial vehicles. With commercial banks no longer playing the ‘relationship’ role they were designated for in capitalist economies, a new shadow banking system hypertrophied, predicated upon funding the financial system through repurchase agreements, or repos, that rendered the securitized debt instruments magically ‘money-like’ in the short term. Into the second decade of the 21st century, shadow banking would become the net provider of cash to the financial system as a whole, with US shadow banks at the apex.4

Why this edifice had crises written all over it is because, in lieu of lending being validated by real economic, production-centered profit making, there are only two ways to deal with debt. One, more debt. Two, austerity. Lending, however, was not directed toward profit-making endeavors but rather toward inflating the value of all manner of ‘assets’, ranging from private and commercial real estate through shares of branded companies, to an array of speculative financial instruments. Just as Nobel-Prize-laureate economists were explaining how business cycles of old had been vanquished by a ‘great moderation’ setting in, waves of a new dynamic of financial bubbles and bursts crashed across the globe from East Asia, through Latin America and Russia, to the US and European Union (EU). Because of the interdependence of the erstwhile commercial banking system and shadow banks, central banks including the ECB, FED, Bank of Japan (BOJ), and Peoples Bank of China (PBOC) morphed into ‘broker-dealers’ of last resort, responding with gales of ‘quantitative easing’ (QE) that fortified distressed balance sheets by taking over non-performing assets from financial systems. You would think that the almost $20-trillion of QE-driven booty in collective central bank hands by the end of 2018 would be inflationary across economies as a whole. Yet, the opposite was the case. With publics trapped in austerity and financial systems attuned to providing “asset inflationary credit,”5 what remained of the real, production-centered economy, predominately of small- and medium-sized firms, was progressively starved of funds, placing it on a deflationary footing.

Nor was US global warmongering and expansionary policy into the 21st century inflationary as it had been in the 1970s. Under the post-Bretton Woods, ‘dirty floating’ global financial architecture, not only did the US dollar anchored only on Treasury IOU’s remain hub currency, but it was also widely adopted as a reserve currency. Even as the US national debt exploded, along with its trade deficit, current-account deficit, and capital-account deficit, notwithstanding the US savings rate hovering around zero, the pivotal role of the dollar constituted an automatic borrowing mechanism. Dollarized financial flows thus streamed into the US to then be recycled in speculative gambits by Wall Street. With its current account deficit financed by savings and trade surpluses of the world, US state spending on global military domination and other budget priorities expanded without ‘crowding out’ private-sector borrowing. Thus, the US spent well in excess of domestic savings plus tax revenue while manipulating interest rates to zero, all without engendering the price inflation that contributed to 1970s stagflation.

Enter COVID-19 and the NATO-Russia Standoff in Ukraine

So, what happened to the neoliberal enchanted world? Remember, even as the COVID-19 pandemic swept the globe, the $10-trillion in QE major central banks added by late 2021 to their $20-trillion balance sheets6 initially only contributed to already burgeoning asset inflation, not consumer price inflation. But, as shown by ShadowStats, which measures US consumer price inflation in both the 1980s and 1990s fashion, based upon maintaining a constant standard of living, a dramatic inflation spike occurs from late 2021, reaching 15% in mid-2022. The consensus among analysts is that current inflation is driven by supply dislocations or ‘shocks’ stemming at the outset from pandemic lockdowns among key exporters such as China that seized up GVCs. This was then exacerbated by the Ukraine war, which ratcheted up prices in energy and commodity markets, a mounting problem the global ramifications of which are sure to play out deleteriously over the foreseeable future.7 On the other hand, the other usual suspect in the neoliberal causal account of inflation, i.e., government spending, is also most definitely not implicated in it this time around.8 Nevertheless, initially viewed as transitory, those arguing that inflation would persist proved to be right.

Because of the gargantuan injection of $5-trillion in QE by the US FED alone during the COVID-19 pandemic, and despite the malaise in stock and bond markets along with crypto carnage, the lending conditions in the ‘decentralized’ bank and private financial intermediary sector remain extremely loose in the US economy. The inflationary consumer-price rises have escalated demand for credit card and home equity loans. Further, the small- and medium-sized business sector, which was bracketed out of central-bank support operations as broker-dealer of last resort to the asset-inflationary economy, now are found to be awash in borrowing opportunities that help fortify the “inflationary biases” in remnants of the real economy.9

Who benefits and who suffers from inflation? Certainly, borrowers in the remaining real, small- and medium-sized business economy benefit, particularly given that recent interest-rate hikes leave real borrowing costs negative. What about workers? With the unionized golden-age labour force largely zapped and production disarticulated across the globe, thus vitiating the dependence of enduring remnants of the production-centered corporate economy on wages paid to workers for sales in ‘national’ markets, there exists no trending of a wage-price spiral in advanced economies. Moreover, differing from the golden age when the most profitable production-centered corporations were also the largest employers, with high wages they paid to their unionized work forces setting an economy wide bar, current preeminent profit-making companies are ICT firms that, relatively speaking, are not major employers in economies. While top ICT firms’ employees are well remunerated, the preponderance of employment opportunities are congregated in lower-profit, lower-wage companies. This pattern is replicated in the financial sector.10 Hence, the evidence from the US economy is that, notwithstanding tight labour markets in the wake of pandemic lockdowns and work from home regimes, wage gains achieved by average workers are well below rates of inflation.11

What about the casino, asset inflationary economy? Instructively, this economy, from which the cycles of bubbles and bursts bailed out by central-bank largess and zero interest rate guarantees emanated, had metastasized by late 2018 into what was dubbed the “everything bubble” and was readying to burst.12 Herculean efforts by central banks forestalled this as the pandemic struck, but now the everything bubble has transmuted into “bubbles bursting everywhere,” from China’s property bubble to the US “government bubble.”13 Where consumer price inflation, as opposed to asset inflation, factors in here resides in the policy response it predictably elicits from the one-trick pony central bank community steeped in monetarist hocus-pocus. That is, raise interest rates. Bank of America strategists have, thus, counted 294 interest rate increases around the world since August 2021.14

It is true, as noted above, that the astronomical interest rate hikes of the Paul Volcker FED in the early 1980s did quash the inflation that swelled from the mid-1970s. However, not only does today’s inflation stem more from conjunctural causes than the structural factors of the wage-price spiral and government welfare-state spending in the waning years of the post-war golden age, the physiognomy of global debt and the opacity of finance across the shadow banking system mitigates against any similar massive interest rate hike. Nevertheless, even relatively minor interest rate increases are likely to cut into the margins of highly leveraged institutional casino bettors such as hedge funds. More ominously, as explored by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), the web of arcane financial instruments has metastasized into at least $65-trillion in debt obligations linked to foreign exchange transactions around the US dollar. Exactly where these sit within the international financial system is difficult to detect because parties and counter-parties dealt with each other ‘over-the-counter’, meaning that, as per the very rationale of the securitization economy of secondary markets, this debt does not appear on financial institution balance sheets. To the extent that interest rate hikes affect the sourcing of dollars to settle these obligations, there is no telling how the subsequent contagion might unfold.15

Whither the Future for Inflation and Deflation

Notwithstanding the conjunctural causes of inflation, it has been claimed, based upon past experiences, that once economies pass the 5%-increase threshold of consumer price inflation, it takes ten years to get it down to the mystical neoliberal 2% target rate.16 In fact, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), global inflation is peaking and will be falling throughout 2023 and 2024, although this will be occurring within the compass of anemic 2.7% growth in the world economy. Under such conditions the IMF cautions that shocks to food and energy supplies carry potential for sparking higher inflation at any time.17 Unperturbed, the US FED continued to raise interest rates in mid-December 2022 to their highest level in fifteen years and is predicted to continue raising them over 2023, at least.18

It needs to be emphasized here, as the consulting firm McKinsey & Company illustrates, that the asset inflationary economy saw global net worth explode between 2000 and the end of 2021 to $610-trillion, amounting to five times that of global GDP. This ‘net worth’ includes financial assets and liabilities of households, governments, and nonfinancial corporations, along with financial assets and liabilities held by financial corporations. Of this wealth spurt, only around 20% actually stemmed from savings channeled into new investment. Around 80% springs from asset inflation. Further, with respect to the investment itself, each dollar of asset inflation engendered $1.90 of additional debt outside of the financial sector.19

What these figures draw to the fore, firstly, is that the real economy of production and trade in which many workers of various sorts are dependent for their livelihood constitutes but a side show for ruling classes and sundry elites plugged into the asset inflationary economy. Thus, policies leveled at the former are certain to be measured by their nominal impact on the latter. After all, the asset inflationary economy was wrought precisely by consistent zero to negative interest rate policies with central banks commandeering security markets by acting as broker-dealer of last resort to the casino. Secondly, the deflationary pall hanging over the remaining real economy that the asset inflationary economy and central bank support of it fostered will not blow over any time soon. Therefore, the austerity that this situation mandates for mass publics to cover the casino markers when bubbles burst is in all our futures.

Finally, for the US economy, as a recent report highlights,20 though its footprint in global GDP and global trade is shrinking, exciting those holding views on the multi-polarity of the global political economy, the role of the US dollar in the world economy continues to endow the US with extraordinary imperial, even super-imperial, structural power. The US dollar is the preeminent currency in foreign exchange reserves, it is the main currency in global payments, and the predominant currency in international banking including shadow banking, as adverted to above and, thus, as also noted with alarm, 60% of foreign currency international claims and liabilities are denominated in it. Further, the US dollar preponderates in global-trade invoicing across GVCs, and it is the US-dollar-based credit allocation across GVCs that lubricates international trade. In the end, global dollar holdings continue to stream into US-based dollar-denominated assets, ensuring the US of global policy flexibility unattainable by any other state. As the report concludes, the US is increasingly unaffected by the goings-on in real economic production and trade outside its borders. •

Endnotes

- Michael J. Webber and David L. Rigby, “Growth and Change in the World Economy Since 1950” in Robert Albritton, Makoto Itoh, Richard Westra and Alan Zuege, (eds.) Phases of Capitalist Development: Booms, Crises and Globalizations (Basingstoke: Palgrave/Macmillan, 2001).

- Richard Westra, “Theorizing the Neoliberal Era,” in Robert Albritton, A Japanese Approach to Stages of Capitalist Development: What Comes Next. Second edition. (Palgrave, 2022).

- World Bank. World Development Report 2008 (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2008) p. 216.

- Richard Westra, Periodizing Capitalism and Capitalist Extinction (Palgrave, 2019) pp. 210-11.

- Michael Hudson, Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy (ISLET, 2015).

- Yardeni Research, Inc., “Central Banks: Monthly Balance Sheets,” November 26 (2021).

- Nouriel Roubini, “The Stagflationary Debt Crisis is Here,” Project Syndicate.

- Joseph E. Stiglitz and Ira Regmi, “The Causes of and Responses to Today’s Inflation,” Roosevelt Institute, December 2022.

- Doug Noland, “Market Thoughts.”

- Herman Mark Schwartz, “Manufacturing Stagnation,” Phenomenal World, November 4 (2021).

- Doug Henwood, “Yes, You Should Worry About Inflation,” Jacobin.

- Satyajit Das, “The Bubble’s Losing Air. Get Ready for a Crisis,” BNN Bloomberg.

- Doug Noland, “Nowhere to Hide,” Credit Bubble Bulletin.

- Jan-Patrick Barnert, “Raging Markets Selloff in Five Charts: $36-Trillion and Counting,” Bloomberg.

- BIS Quarterly Review, International banking and financial market developments, December 2022.

- VBL, “JPM: ‘For countries that see CPI exceed 5%, it takes around 10 years for CPI to fall back to 2%.’,” Zero Hedge, December 14, 2022.

- International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook: Countering the Cost-of-Living Crisis, October 2022.

- CNBC, “Fed raises interest rates half a point to highest level in 15 years.”

- McKinsey & Company, “Global balance sheet 2022: Enter volatility,” December 15, 2022.

- New York Federal Reserve Staff Reports, The Dollar’s Imperial Circle, No. 1045 December 2022.